The barbershop has been an important institution in the African-American community for generations. But what many don’t know is that up until about the Reconstruction Era, pretty much all barbers in the United States — whether they cut the hair of white men or black men — were African-American, and that barbering provided many black men a good enough living to enter the upper middle class.

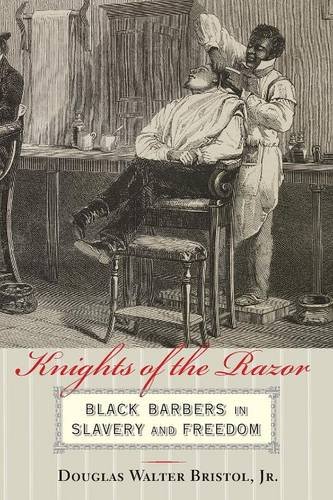

Today on the show, I talk to historian Douglas Bristol about his book recounting this lost part of American male history. It’s called Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom. Today on the show, Doug and I discuss the rise of the black barber in slaveholding states in the South, the influence black barbers had in the white community, and how black barbers paved the way for the modern barbershop. We also discuss the factors that led to the segregation of the barbershop and why it maintained a stronger allegiance among black men compared to their white counterparts.

Show Highlights

- The low status of the barber profession in the 19th century

- The high status a black slave barber could gain in the white community

- The tensions that existed between black barbers and their white customers

- How one slave barber ended up financially supporting his master

- How freed black slave barbers became some of the wealthiest men in the African-American community

- The political influence many black barbers had in the Republican Party after the Civil War

- How black barbers created the luxury barbershop in the 19th century

- What black leaders like Frederick Douglass thought of successful black barbers

- The apprenticeship process the Knights of the Razors developed to train future black barbers

- How the apprenticeship system helped cement the centrality of the barbershop in the African-American community

- The successful black barbers who started the first insurance companies for African-Americans

- Why white men preferred to get their haircut by black barbers despite the influx of white European barbers in the late 19th century

- How state licensing in the late 19th century helped lead to the segregation of the barbershop

- How the invention of the safety razor contributed to the decline of the barbershop in the late 19th century

- Why the barbershop had a stronger toehold among African-American men than with white men

- And much more!

Resources/Studies/People Mentioned in Podcast

- Why Every Man Should Go to a Barbershop

- Barbershop (movie)

- George Myers

- James Rapier

- Reconstruction

- Frederick Douglass

- Frederick Douglass: How a Slave Was Made a Man

- Mastery: The Three Vital Steps of the Apprenticeship Phase

- Archetypes of American Manhood: The Heroic Artisan

- William Johnson

- Alonzo Herndon

- John Merrick

- King C. Gillette

- How to Shave Like Your Grandpa: Safety Razor Shaving

Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom is a great read into a forgotten part of the American history of men. If you love going to barbershops (and we hope you do!), I highly recommend picking up a copy of this book to learn more about the history of this virile institution.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Carnivore Club. Get a box of artisanal meats sent directly to your door. Use discount code AOM at checkout for 15% off your first order.

Proper Cloth. Get a custom fitted dress shirt without measuring yourself. Get $20 off on your first shirt from Proper Cloth by using gift code MANLINESS at checkout.

Shari’s Berries. Get some chocolatey dipped strawberries for just $19.99 sent directly to your door. Use code MANLINESS to claim the offer.

And thanks to Creative Audio Lab in Tulsa, OK for editing our podcast!

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. The barbershop has been an important institution in the African-American community for generations, but what many don’t know is up until about the Reconstruction era, pretty much all barbers in the United States, whether they cut the hair of white men or black men, they were African-American, and that barbering provided many black men a good enough living to enter the upper middle class even back in the 19th century.

Well, today on the show, I talk to historian Douglas Bristol about his book recounting this lost part of American male history. It’s called Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom. Today on the show, Doug and I discuss the rise of the black barber in slaveholding states in the South, the influence black barbers had in the white community, and how black barbers paved the way for the modern barbershop. We also discuss the factors that led to the segregation of the barbershop and why the barbershop maintained a stronger allegiance among black men compared to their white counterparts.

Really fascinating show. After the show’s over, check out the show notes at AOM.is/blackbarber.

Douglas Bristol, welcome to the show.

Douglas Bristol: Well, hi Brett. I’m glad to be here.

Brett McKay: You’re a professor of history. You got a great book out that I read because barbershops are something we’re interested here at the Art of Manliness. But you explore the history of barbershops, particularly black barbers in American history. The book is called Knights of the Razor. Now, barbershops have sort of become this idealized American institution and for the African-American community the black barbershop has been like a foundational community touchstone for men.

What I thought was interesting, you talk about in your book is that before the 20th century black barbers primarily serviced a white clientele and in fact, as you highlight in your book, most barbers in America before the Civil War were black.

What was the status of the barber profession in the late 18th and early 19th century in America that caused more black men to go into the profession as opposed to white men?

Douglas Bristol: Wow. We’ve touched on a lot of issues that are involved in this book. As you said, I want to follow up and just talk about how central a place black barbershops are to today’s African-American community. I’m thinking about the movie Barbershop and the character everybody loves, Eddie, talks about it’s the black man’s country club. It’s the one place where black men can speak freely without being under surveillance from whites and think about what they want. That’s why Civil Rights protests were planned there. In fact, I’m in Mississippi, and there was a barbershop in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, so many of the men migrated to Chicago that the barber moved to Chicago and called it The Hattiesburg Barbershop.

As you pointed out, my book is about this forgotten chapter in the history of black barbers in the 18th and 19th century when they served white men rather than black men. What makes it even more curious when you think about it is if you look at 19th century portraits or whatnot, the guys were pretty shaggy. They weren’t that worried about their haircut. You went to a barbershop because you wanted a shave and the only way to get that was with a straight edge razor. This is the story of the black man’s razor at the white man’s throat.

Of course, you’re asking a great question. Why did that become the common thing in the country? The answer has a lot to do with understanding race relations. If you think about it, this is still true in many ways. Most white men don’t really go to barbershops anymore. When we go to a shop we tend to have someone with a different status than us cut our hair. It’s a woman. It’s an immigrant. There’s a phenomenon that goes on in barbering that traces its roots back to 16th century Europe when one of the ways that people asserted that they were gentlemen is that they took care of their hair and shaved the whiskers from their face. To groom yourself was originally thought of as a way of distinguishing yourself in society and you relied on servants to do that. It’s the association of personal service, tending to your body by cutting your hair and shaving your whiskers, that makes barbering associated outside the black community with low status.

In the 18th and 19th century we saw the first slave barbers are actually owned by planters of large plantations. This is a handful, maybe 50 planters had enough slaves, 100 or more, where they could actually have house servants who’d include what they called a slave waiting man who would often not only cut his master’s hair and take care of his clothes and shave him but also would serve as his majordomo helping keep books, supervising other slaves on the plantation.

What really is key, and this gets to the strange duality of barbers that you really see in 19th century black barbers. On the one hand, because of the racial difference and early on because the black men were the property of the people they served, the status is very unequal. However, going back to Eddie from Barbershop, he points out one of the functions of a barber is to be someone’s fashion coach. That really gives that person authority because you go to a barber hoping they’re going to make you look good, look hip, and that gives them power. There’s always a tension in relationship between the white customer and the black barber.

Brett McKay: I thought it was interesting too, was going back to this idea of the slave barbers for these Southern planters. They would often pick one of their slaves to be what they called the waiting man. The waiting men would actually become very genteel. They would wear powdered wigs and have the nice clothes and they got to listen in on conversations of their masters with other white men in the elite circles. They did sort of become elite themselves in a way. As you said, their masters relied on their waiting man to make them look awesome. How did that dynamic there play out between master and slave, where you had a slave who was, in some cases, just as genteel as you were, cutting your hair and actually giving you information on how to present yourself better?

Douglas Bristol: Maybe the best way to answer that question is to give an example of a very wealthy planter named Landon Carter who was a third-generation planter, who owned several thousand acres, over 100 slaves, and his really up and down relationship with his waiting man who was named Nassau.

There’s a couple things in this story that really get at important issues. The key thing with talking about the slave barber has power because he understands how to make his master look the right way to acquire status, is acculturation. One of the main findings in the last 20 years in the history of slavery, especially in the period before the American Revolution, slaves who had learned Anglo-American culture were more useful to their masters, but at the same time, they were more troublesome because they understood the master’s world. To go back to that example of Landon Carter and Nassau, Carter actually allowed Nassau to treat, he was basically a folk doctor so he treated even members of Carter’s own family. He collected debts. He took care of his horses. But he also had a really bad drinking habit. Nassau, it seemed, just delighted in thumbing his nose at his master’s face. This is all from Landon Carter’s diary.

One of the stories that I put in the book talks about how Landon Carter goes to a party at another plantation house and when he leaves he can’t find Nassau to drive him home because Nassau’s off drinking somewhere and Landon Carter ends up getting his carriage stuck in the mud. He’s pulling this thing out and then along comes riding by, comes Nassau and his son drunk as skunks, riding, laughing, and just leaving him in the mud. There’s this sense of the tension because of that power on both sides of the relationship that had to do with the familiarity of culture.

Brett McKay: What did the slave barbers, were they able to gain some respect within elite white circles because of their gentility? I think you gave an example of one guy who did the hair for a lady. I didn’t know this. Back in the 18th century when everyone wore powdered wigs, the ladies had to shave their heads. I didn’t know that.

Douglas Bristol: Right. That’s how the wigs were possible. This, of course, is really surprising because later in the 19th century racial stereotypes changed and we get the notion that all black men secretly wished to rape white women, so you do everything possible, it’s the whole foundation for segregation, to keep them separate. And yet, in the years just after the Haitian slave revolt, Pierre Toussaint, who was a slave who left with his master’s family after the Haitian slave revolt, he was part of this middling class of people of color who were mixed race, who were essentially the middle-men, the supervisors, the managers on plantations in Haiti. They had to flee the island when they have this successful slave revolt, and he ends up supporting his master’s family living in New York City. His real appeal is that people thought he was the perfect gentleman, so much so that one of his customers actually wrote an admiring biography of Toussaint.

Brett McKay: I thought it was crazy, too, where the slave, or the former slave or the slave was supporting the master’s family from his own pocket.

Douglas Bristol: Well, as I discuss in the book, it really makes sense for him because black skin was associated with being degraded. There are some letters that he corresponds with friends where he talks about his frustration that whites are incapable of really understanding that he’s a thinking person just like themselves.

With Toussaint, he needed to support his master because he needs to have some claim to polite society. By living with his master, he was respectable which made it acceptable for him to take care of these first-class women who he was serving. Later on, when his masters passed away, he actually continues to hold dinner parties for his customers, but he will not sit and eat with the white people. He’s maintaining that distance, but by entertaining he keeps that connection to elite genteel society.

Brett McKay: I think you talk about this too, it’s sort of related, that after the revolution there began to be this emancipation of slaves in the North and in the upper South. You talk about how the former barber slaves would maintain connections with their former masters even after they were freed in order to transition more smoothly to being a freedman.

Douglas Bristol: Right. That relationship is important to think of. We think of emancipation means the slaves you can free and go off and have a completely independent life. That was not possible because free blacks in the South had very limited legal rights. For example, if you own a business you need to be able to collect debts, but since black people couldn’t testify against whites in court, it was a very practical matter that you had to have some kind of a white patron who would act on your behalf in circumstances such as that.

Brett McKay: Many of them maintained connections with them.

Before the Civil War, we mentioned this earlier, most barbers were black and served primarily a white clientele. Because barber was considered a low-status position, white people thought it was beneath them to do that, so black people stepped in to fill that position. But as you said earlier at the very beginning, there’s this weird social dynamic going on. You had a black man who was seen as subservient, degraded, with a razor blade to the throat of a white man who was in power. What was the social dynamic like in the barbershops between a black business owner and a white patron before the Civil War?

Douglas Bristol: That’s an excellent question because it’s a real ritual of power. When the white customer would come in, no matter if he was speaking to the shop’s owner, no matter if he had known the barber for years, he would feel free to command to know whether he had washed his hands recently or if the towel was clean, so clearly asserting his authority over a black man. But then he gets in the chair and, of course, leans back and exposes his throat. Once he’s lathered up he can’t even speak because if he opens his mouth it would be full of shaving cream. My understanding of that is that it reaffirms their greater power by being white because they had no question that black men were inferior to them. So, that demonstrates their mastery to put their lives at risk by exposing their throat to a black man and knowing nothing would ever happen.

Brett McKay: Did the social dynamics differ depending on what part of the country you were in, if you were in the Northern States or the Mid-Atlantic States or the Deep South?

Douglas Bristol: There’s two things to talk about that. First is, people often assume this is a Southern story because most African Americans lived in the South, and it’s not. Black barbers were the most consistently successful black businessmen throughout the entire country and, in fact, there’s good evidence that suggests the first black men to live in Chicago, Los Angeles, and Seattle were black barbers because this niche was so well-established that they could go anywhere and open up a shop.

Brett McKay: Did the dynamic change between black business owners and their white clients depending on if they were in Chicago or New York or Charleston?

Douglas Bristol: Before the Civil War, you really don’t see any difference. In fact, some British visitors, they’re very curious about this phenomenon, because as one English traveler wrote, in most circumstances white men avoid being around black men and then in this circumstance they seem to love going to the barbershop. They noticed that was even true in New York City. One traveler gave the explanation that it allows them to play the master in a society where there really aren’t slaves anymore because whites simply could get away with a certain demeanor with black servants that white servants would not tolerate.

Now, after the Civil War, everything changes because, of course, the Republican party is dominant in the North and it was the party of emancipation. The best example is George Myers, the famous barber of Cleveland, Ohio, who was a close friend of Mark Hanna. He got enough black votes at the convention to get William McKinley nominated for the Republican party’s nomination for President. There were barbers like Myers that played an active role in patronage politics because, of course, what would be the main thing the white men would talk about in the shop was politics. Politics and business. They were in a context where Republican party politics in the North made it acceptable for black men to participate. The relationship was completely different because they were partners, unequal partners, in making sure that the Republican party rode to victory at every election.

Brett McKay: And in the South, it was probably not like that.

Douglas Bristol: No, not at all. Although interestingly enough, John Rapier, Sr., who lived in Florence, Alabama, had several of his sons became barbers, and one of his sons actually became a Reconstruction congressman, but John Sr. was the first African-American official in the state of Alabama. There’s a petition, so we know why they decided to pick him, he was a voting registrar, of all things, in Alabama and whites supporting this appointment wrote that we can trust our barber John to be conservative. So, a southern barber could be trusted to be discreet and to never challenge the social order in front of whites.

Brett McKay: I thought it was interesting too, I had no idea about this, but before the Civil War, and despite being seen as a subservient occupation, black barbers became some of the wealthiest men in antebellum America. Some of them were leaving estates of a hundred thousand dollars behind. Any notable examples of financially successful black barbers that you came across?

Douglas Bristol: The interesting thing, I can tell you the names of people who had a lot of money, but they tended not to be people who were famous in other regards, so I didn’t focus on them as much. I think the larger issue is that collectively what the Knights of the Razor, as they liked to call themselves, did is they were able to invent something new. They were a real entrepreneur where they’re not only risking their money, but they’re coming up with a new innovative idea. That idea was the first-class barber shop. What they were doing with this in the 1820s this fad hit American cities of having hotels that had what were referred to as saloons, which was a corruption of salon, which is a public room that you would find in an aristocratic house. These were going to be palaces of the people. The idea was that Americans can celebrate their equality and their prosperity by mingling together in these public settings where they were clearly very genteel.

Barbers, by adopting some of the trappings of a Victorian parlor, the drapes, the upholstery, so the very first barber chairs that we would recognize were adapted by black men. They’d have upholstered chairs that would recline which was a considerable advance over what came before. Of course, these are large establishments, centrally located often in the town’s leading hotel. It’s their development of service that included the experience of luxury that made them able to fend off white competitors for the rest of the 19th century. Of course, that’s what led to the profit.

Brett McKay: But I thought it was interesting too, they were able to fend off white competitors, and we’ll get into more about how white barbers kind of broke monopoly on the barber trade later on. You talk about some of these individuals who made lots of money. They seemed sort of ambivalent about their occupation. They were like, “Yeah, I made a lot of money,” but they still felt the sting of low status because they were a barber.

Douglas Bristol: I think you might be referring to some of the comments made by black leaders such as Frederick Douglass or Martin Delany or David Walker, who all, at different points, criticized barbers for pulling down the race by reinforcing the stereotypes that black people are servile. This is something that I’m actually having students write a paper about this where they’re looking at these editorials and debating, you know, writing a paper talking about was that a fair criticism or not? One of the things that came up in discussion with the students is there are some similar comments about rap stars today, like Flavor Flav, many black people thinks make blacks look ridiculous. He’s mainly selling albums to teenage white men. It’s a similar phenomenon. We can understand it by comparison.

Brett McKay: Right. That is interesting. A comparison.

I thought that was interesting that in the African-American community they were sort of ambivalent about barbers. On the one hand, they were proud of the Knights of the Razor because they were entrepreneurial. They were business owners. It was a path to middle-class living. At the same time, as you said, Frederick Douglass criticized them because they were doing this through the role of a barber which was a subservient position.

Douglas Bristol: Well, like I do in the book, you have to look at what Douglass was asking to see if it’s reasonable. You can get the idea that you’re not, as people would say, representing well to play the fool and shuck and grin for white customers. But what Douglass, in a series of editorials that he published in his newspaper, called for parents to make their children mechanics and not waiters and barbers and other forms of servants. The problem with that is that it was not possible for the overwhelming majority of free black people to learn a trade because the white skilled craftsmen refused to train them as apprentices. Frederick Douglass himself was a skilled ship’s caulker when he ran away from Maryland and gained his freedom and he was unable to gain employment in that trade in the North.

Part of what’s going on is it’s an aspiration for the African-American community. Again, to try and draw a parallel to the present, that would be like a black leader today saying people in South Central L.A. need to become computer programmers because that’s the cutting-edge technology. It’s the kind of expertise that’s going to gain lots of money. That makes sense on the face of it, but it’s unlikely that people have the skills or the access that they could actually do that. That’s why in the book, I agree with barbers who defended themselves and said that “Look, you have to realize we are the majority of business owners and business ownership allows us to build churches and keep our wives at home and send our kids to school and promote a more respectable black elite.”

Brett McKay: Going back to this idea of job training, telling to become a mechanic that was probably impossible because white people wouldn’t train them, but within the Knights of the Razor, as they called themselves, they created a journeyman’s process, an apprenticeship process to train other black men in how to become a barber.

Douglas Bristol: Yeah. That’s really something I think is really key to understanding, not only why they were successful because this is a book about business success by small entrepreneurs, but it’s also about why they’ve established a tradition of men supporting other men, of mutual aid that continues to exist in today’s barbershop.

One of the best sources for understanding antebellum traditions of working with apprentices and supporting them comes from an extraordinary document which is the diary of William Johnson. William Johnson was a free black man. He was the leading black barber in Natchez, Mississippi when it was the heart of the cotton kingdom in the 1830s and the 1840s. He left behind a 2,000-page diary which is the longest single narrative written by any African American before the Civil War. Because he knew everyone, it’s the best single source on the history of Natchez at that time. For our purposes, it’s really interesting to see what he wrote about … He had over 20 young men live in his house as apprentices. This is not the community college experience that we might picture with an apprentice now. Families, often single mothers, would drop their kid off with William Johnson when they were 10, 11, 12 years old and the understanding was Johnson would not only teach them the barber trade, or the tonsorial arts as they were called, but make sure they grew up to be respectable men who could read and write, who went to church.

It’s very interesting to see Johnson as a figure. He had a white father and a black mother, so he’s a man who’s kind of in between. He doesn’t fit in with the slave community, but the whites won’t accept him. Some of these apprentices represent the only people that he could identify because they would come, often white fathers would place their illegitimate mixed race son with him. He has, for example, one of those apprentices was William Winston, who was named after Lieutenant Governor Winston of Mississippi who was his father. Johnson really takes a shine to Winston in being amused at him fighting back against the older boys or that he would not attend darkie parties. He was a more reserved, dignified person. And ultimately ends up helping Winston gain his own shop so he can be an independent black barber.

This is, of course, the real tradition of mutual aid. Teach people the trade, but teach them how to be strong black men. Help them become their own businessmen. Then when other barbers would grow older, provide them with employment.

At the end of the 19th century, this undergoes a dramatic transformation. It has to do with the rise of black-owned business for black customers. With urban migration, African Americans find they have enough disposable income they can support, first off, their own black barbershops. Most African Americans before then had simply cut each other’s hair at home. But more importantly, they can support insurance companies.

I think maybe before you were wanting me to talk about Alonzo Herndon and John Merrick, who were two very wealthy barbers. Herndon in Atlanta. Merrick in Durham, North Carolina. Each man established insurance companies to sell insurance to blacks at a time when Prudential Insurance, for example, simply refused to write policies to black customers. They said their mortality rate was too high.

The reason I’m talking about these companies, though, is I’ve argued that Herndon and Merrick made their businesses so successful … And by the way, Merrick’s North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company became the largest black-owned business in the world up to the 1960s. It was successful, though, because they were able to translate that tradition of mutual aid to selling insurance, to how they recruited and groomed and mentored young salesmen, made them district managers, had social gatherings, that reflect what we saw barbers doing 50 years earlier.

There is a direct connection between black business in the present, especially black barbershops, where it’s about making sure that members of the community help each other and economic self-help, and the traditions of these barbers in the 19th century, who had very different lives because they served white customers.

Brett McKay: I thought it was interesting too. In the tail end of the 19th century you started seeing a large increase of immigration from Europe. From Germany. From Italy. These people, a lot of the men, they were barbers. They came to be barbers and they started competing with black barbers in America. But you talk about in the book that even though there were these white men who were barbers offering the services, a lot of white men still preferred to be barbered by black barbers. Why was that?

Douglas Bristol: An immigrant was a white man and that was not a clear marker of difference in status. White men preferred to be waited on by someone who was clearly their inferior. Also, especially in the North with this competition, the farther south you went, the stronger was the hold of the black barbers over white customers. But in the North, the other facet is in first-class shops the barbers had much more in common with their customers than an Italian immigrant. Turns out the skill that Italian immigrants in the late 19th century were most likely to bring from Italy was barbering. A black barber who’s involved in Republican party politics, who has extensive business interests of his own, is going to have more in common with well-to-do white customers than a recent immigrant off the boat.

Of course, this is all going to change. One thing I was hoping we would have a chance to talk about is the impact of licensing and how that was used by unions to exclude African Americans, ultimately, from the trade.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Let’s talk about that because in every state you have to be licensed to be a barber.

Douglas Bristol: Right. Two things really contributed to that. This both happen in the 1880s. The first is we start to get a more wide-spread understanding that germs cause disease and a French scientist publishes an article that scandalizes people because he looks at a styptic pencil, which is what you use after you cut your face shaving, and found sixty thousand different kinds of germs living on this. There’s this sense that barber shops are cesspools of contagious disease.

At the same time there’s concerns about the sanitation of barbershops, we also see the first of the barber schools, so for profit commercial barber schools. A man named A.B. Moler set these up all over the country, wrote textbooks. So, he wrote the first text for barber colleges. This created a flood of what were called cheap barbers because they were not very well trained and, consequently, couldn’t charge much. They ruined the trade in a sense that they drove down prices for shaves and haircuts.

There was a union, the Journeyman Barbers’ International Union of America, that was associated with the American Federation of Labor. The leaders, mostly second-, third-generation German-Americans, saw their opportunity to seize on the issue of sanitation to limit competition and, while they’re at it, finally exclude the blacks in the first-class barbershops. The pretext for licensing laws was to ensure the sanitation of barbershops and protect public health. And the idea was, and they really traded on gross stereotypes about Italian immigrants or African Americans being disease carriers because they were unclean, sexually promiscuous. So, starting in the 1880s we see the first laws being passed.

For a while, I had mentioned George Myers, the barber, the king-maker, that helps William McKinley become president, who’s a barber in Cleveland, men like him are able to fight back by retrofitting, reinventing the barbershop one more time. It’s something really closer to today where there’s lots of sinks. You sterilize combs in Barbicide. They had elaborate steamers to sterilize the razors and whatnot. For a time being, the black barbers that owned the best shops were able to update to this new regime. But in the long run, licensing driven by concerns about sanitation will exclude them.

Then, of course, one thing I didn’t get a chance to talk about in my book, is when William Gillette invents his razor, he claims that this is the most sanitary option is to not have to go to the barbershop at all. There are early ads that say isn’t it annoying when you go to the barbershop and your barber’s hands smell like garlic and cheap cigars and wouldn’t you rather just shave yourself at home? Again, an appeal, greater sanitation and a chance to not associate with people who you consider your social inferiors.

Brett McKay: Besides licensing, what other factors eventually led to the segregation of the barbershop in America where you have black barbers servicing primarily African-American men and white barbers servicing primarily white men? Even now, the white barbershop is kind of making a resurgence, but it’s kind of defunct.

Douglas Bristol: Yeah, it’s really the African-American community that’s been loyal to its barbershops. It really has to do with the rise of segregation at the end of the 19th century. It’s ironic, the barbers were criticized by black leaders because they wouldn’t serve other black men. They ran, in effect, segregated institutions. But as historians have shown, the real fundamental change in race relations in the 1890s, that’s when we see the height of lynching, for example. Increasingly, younger generations of white men do not want a black barber.

I actually found a gentleman named George Hall in Mobile, back in the 1990s, and in the 20s, he had served in his uncle’s barbershop in Mobile where they still served white men, but he said at that point it was all very old men and the younger men didn’t come in the shop. As race relations grew worse, younger whites became reluctant to go to black barbershops, but at the same time the opportunity I discussed before, the greater earning power of wage earning urban black people, meant that many of the barbers I studied simply just switched to serving black men, which in the long run was a more satisfying situation for them anyway.

Brett McKay: Why do you think the black barbershop has endured while the barbershop in the white community hasn’t fared so well?

Douglas Bristol: Well, it’s that tradition of mutual aid. I think it’s reinforced, so there’s this sense that a barber is something more than someone who’s going to give you a haircut. This is a coach, a counselor, financial advisor, so they’re idea of barbers taking care of each other extends to their customers, especially now that they have so much in common. They’re the same race. They live in the same community.

I think too, though, another reason why this is so particular to the African-American community is black barbershops reaffirm the masculinity of black men, which is questioned in many places, that they’re real men. A lot of stereotypes, for example, critical of people on public assistance, that black men don’t make good providers and whatnot. So, in mainstream life where they’re worried about police profiling them, in a black barbershop they get respected as a man and taken seriously as a man. There are few other places where they’re going to find that.

Brett McKay: Douglas, this has been a great conversation. Is there anywhere where people can go to learn more about the book?

Douglas Bristol: Yeah, they sure can. If they look at the Johns Hopkins University website, there’s a couple links for videos I’ve made about the book. Of course, you can get it on Amazon.com. It came out last year in paperback. I hope people will take the opportunity to look at the book themselves.

Brett McKay: I hope they do because it’s a really fascinating part of history that gets overlooked.

Well, Douglas Bristol, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Douglas Bristol: Hey, Brett, it was really nice talking to you. Thanks for your time.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Douglas Bristol. He’s the author of the book Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom. It’s available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. Check it out.

Also, check out our show notes at AOM.is/blackbarber where you can find the links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoy this show, I’d appreciate it if you’d give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher.

Our show is edited by Creative Audio lab here in Tulsa, Oklahoma. If you have any audio editing needs check them out at creativeaudiolab.com.

Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.