The ability to grow a beard is what separates boys from men and except for a few rare instances of bearded ladies, men from women. Because it’s a uniquely masculine feature, facial hair has played an important role in forming our ideas about manhood. Today on the show, I talk to a cultural historian who specializes in the history of facial hair about the cultural, political, and religious history of the beard. His name is Christopher Oldstone-Moore and in his latest book Of Beards and Men he takes readers on a tour through the history of facial hair starting with cavemen and going all the way to the hipster beard of the 21st century.

We begin our conversation talking about why male humans grow beards in the first place and then take a look at the spiritual and political significance of beards and shaving beginning with the ancient Sumerians through medieval Europeans. We then discuss why the Greeks were big on beards until Alexander the Great and why the Ancient Romans were bare-faced until the days of the early empire. We also discuss Jesus’ beard and why many early Christians actually depicted him as clean shaven. We end our conversation talking about the great beards of the 19th century, why clean shaveness took precedence in the 20th (and no, it’s not because of the military’s use of gas masks) and the cultural meanings of facial hair today. Whether you’re bearded or bare-faced, this podcast is going to leave you with lots of new insights about the hair that grows on your masculine mug.

Show Highlights

- How a professor of Western civilization came to specialize in facial hair

- Christopher’s own feelings on being bearded

- Why humans have facial hair in the first place

- Why did men start shaving?

- The signals that a large and lengthy beard sent in the ancient world

- Why having your beard forcibly shaved off was a humiliating punishment

- Why shaving came to represent godliness and power

- How Roman emperor Hadrian ushered in the first resurgence of the beard

- The history and portrayals of Jesus’ beard

- Beardedness in the Middle Ages

- The up and down nature of the popularity of facial hair throughout various historical ages

- Why Romanticism embraced the beard faster than any other era

- How facial hair came to have a bit of a generational divide

- How Abraham Lincoln’s beard came to be

- The cultural significance of the mustache — especially in the military

- The perfect storm of science, culture, and corporate work environments that led to the clean-shaven men of the 20th century

- What’s the status of the beard today?

- The role of the beard in society today

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- How to Grow a Beard

- Shaving Rituals from Around the World

- The Science of Facial Hair: What Signals Do Beards Send?

- The 35 Manliest Mustaches of All-Time

- The 12 Most Infamous Mustaches of All-Time

- Advice on Being a Man from 8 Neighborhood Barbers

- Mid-1800s Punch Magazine cartoon lampooning facial hair

- Art of Manliness Mustache Style Guide

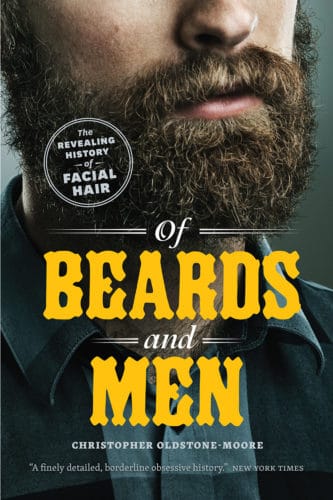

Of Beards and Men is utterly fascinating. After you’re done reading it, you’ll never look at beards the same way. Pick up a copy on Amazon.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

The Illustrated Art of Manliness. The Greatest Father’s Day Gift of All Time. OF. ALL. TIME.

The Black Tux. Online no-hassle tux rentals with free shipping. Get $20 off by visiting theblacktux.com/manliness.

Buck Mason. Classic, American staples like tees, henleys, and jeans sent directly to your door. Visit buckmason.com/manliness to get FREE shipping on your first Crew Slub Tee.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. Well, the ability to grow a beard is what separates boys from men, and except for a few rare instances of bearded ladies, men from women. Because it’s a uniquely masculine feature, facial hair has played an important role in forming our ideas about manhood. Today on the show I talk to a cultural historian who specializes in the history of facial hair, to discuss the cultural, political and religious implication of the beard. His name is Christopher Oldstone-Moore and in his book Of Beards and Men he takes readers on a tour through the history of facial hair starting with cavemen and going all the way to the hipster beard of the 21st century.

We begin our conversation talking about why male humans grow beards in the first place and then take a look at the spiritual and political significance of beards and shaving beginning with the ancient Sumerians and going all the way through medieval Europeans. We then discuss why the Greeks were big on beards until Alexander the Great and why the Ancient Romans were bare-faced until the days of the early empire. We also discuss Jesus’ beard and why many early Christians actually depicted him as clean shaven. We end our conversation talking about the great beards of the 19th century, why clean shave-ness took precedence in the 20th century (and no, it’s not because of the military’s use of gas masks) and the cultural meanings of facial hair today. Whether you’re bearded or bare-faced, this podcast is going to leave you with lots of insights about the hair that grows on your masculine mug. After the show is over, check out the show notes at aom.is/beards.

Christopher Oldstone-Moore, welcome to the show.

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Thank you for having me.

Brett McKay: So you recently published a book, Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair. You’re a Professor of Western Civilization and it says in your CV that you have a focus on facial hair and it’s intersection with the changing ideas of masculinity. I’m curious, how does a Professor of Western Civilization end up specializing in the history of facial hair?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Well, the short answer to that question is that I’m looking for fun things to put into my lectures of Social History. Actually it started out with the question of why men did shave? That’s the original question and I was thinking about the Romans in the Classical Period of Julius Caesar and so forth and all their busts are all shaven men and I thought, “When did that start? How did that get going and is that a Roman thing?” So I started looking around trying to find some information and was pretty surprised to find that we, that is to say academia, knew almost nothing about the history of shaving, facial hair and it was just completely overlooked and so I got more and more interested in it. Then I fell completely into the rabbit hole.

Brett McKay: And here we are today. Do you yourself have a beard or do you shave?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: You know, I go back and forth. Right now I do have a beard. I often have a beard during the summertime when I’m camping and so forth and so on. Sometimes I shave it off. I guess I’m indecisive and in my book I have a picture of both me, beard and not bearded, but it also reflects history, that’s the way history’s worked too.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about the question why do humans have beards in the first place? Cuz you point out other primates don’t have copious amounts of facial hair like we do. Do biologists have an idea why humans evolved to have facial hair?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Well it’s a great conundrum and it’s been debated for decades. There are a lot of good reasons but we can’t be dead sure because it’s impossible to recreate the conditions of about 50,000 years ago or so when these things evolved, but I think that the predominate theory is still Darwin’s idea that beards in an ornament. That is to say they are to demonstrate a man’s maturity, health, strength, those kinds of qualities that would make him a good sexual partner, and therefore is an ornament, a signal to sexual partners that he’s the kind of guy that you want.

There’s a lot of interesting evidence of that, both in psychological research, but also in other, microbiological research and for example, the study of animals and the comparisons say with feathers. There’s an obvious ornament case, and bird females look at males and look at their plumage and the bigger the better the plumage, the more interested they are. Biologists are thinking, “Well, maybe that’s what we’re doing with the beards too.” Here’s the interesting part, they debate about whether why is this happening? Why do birds grow these ridiculous feathers like the peacock, for example.

They discovered that really it’s what they call ‘honest advertising’. That is to say it really does take a healthy peacock to grow impressive feathers and so when you see impressive feathers, when a female bird sees impressive feathers, it’s not just a trick, it’s the real thing, that bird is a healthy bird, so it’s a good sexual partner. So maybe if you have a big healthy beard, that’s a good sign.

Brett McKay: Right, right. Yeah, the other theory I’ve heard out there is that it’s selection for, I guess the beard somehow provided protection to hits to the face. I’ve heard that theory also as well but-

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Well, biologists don’t pay much attention to that. There isn’t really much evidence of that. When you think about it, if beards were meant to be thick, protecting important parts of your neck or your face or anything like that, it wouldn’t grow the way it does. I think people have noticed, for example, a lot of people say “Oh, it protects your neck,” well, it doesn’t actually grow on your neck, you know. It grows on your face, it grows on your chin and does your chin need protection? Where it’s thickest is on the chin, does your chin need protection? Not particularly.

What does impress evolutionary biologists is the fact that the chin, around the mouth, our human chins are actually artificially enlarged for visual effect. To look impressive, to look strong, our mouth area is something that we use to threaten people with, our teeth and to have an impressive chin, an impressive face, impressive mouth, is intimidating, it looks strong and that’s the other part of the theory is that not only is it an ornament, but it could be a weapon. That is to say it shows how threatening and strong we are, and so it’s a warning to other men as well as an attraction to women, so it can kind of serve both roles.

Brett McKay: Okay, if beards, under this theory, if they’re sort of as an ornament of attraction for women and possibly a deterrent to other men, why did humans start shaving and when did they start shaving?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Yeah, exactly, good question, I mean, that’s kind of where I started this whole thing. You think of ancient people as being big-bearded people. Ancients Greeks, the ancient Mesopotamians and so forth, the Syrians. Actually shaving really starts right at the beginning of civilization, as far back as we can look and probably before.

One of the reasons to do that, to shave it, is to indicate a different kind, a special kind, of masculinity, not an ordinary, natural kind that we’re born as, but something that we make ourselves into. The most special form of masculinity that the ancient world was the priesthood. Which, there’s a joke about prostitution, prostitutes are the original professionals, but the truth is that the priests were the original professionals. They were the first people to be set aside for a special task, very important, special task. That special task was to interact with the gods and to win their favor on behalf of all the rest of us.

It took special preparation and training and skills. As part of that separation and preparation, they developed this idea of shaving. Now, I think it’s pretty clear that one has to be in mind that these early priests, and we’re going back 5,000 years ago, these early priests in Mesopotamia and Egypt, they shaved their entire bodies, not just their faces. All the hair was removed and in many cases, they appeared nude in front of the gods, so they removed their clothing, they removed their hair. I think the idea is to purify themselves, in some ways erase their dirty humanity and to prepare themselves to be as clean and as pure as possible as they approach the gods.

You read this in the Bible, and all the temples had purification pools where you had to go through a ritual cleansing before you approach the holy sanctuary. A shaving of hair and ultimately, shaving the beards off, originated there with that idea of purification.

Brett McKay: So while that was going on though, in ancient Mesopotamia and in Egypt, the beard still played an important roles in a man’s identity. If you look at those old carvings from Mesopotamia, you see these guys with their ginormous beards. The ancient Egyptians would put on fake beards, sort of that little strip, right? So what’s going on there? You had the priesthood who saw facial hair as making them somehow un-pure, but then also at the same time you had these kings who said, “No, the facial hair makes me awesome and maybe god-like, too.”

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Well, and you kind of have a separation of roles, different types of masculinity, so you have the priestly masculinity, and that’s a certain kind of power and then you have the warrior masculinity and that’s a different kind of power. Not surprisingly, they have different looks and it goes back to what I suggested about this idea of the beard as a weapon, as a threat. You look impressive, you look strong, so yeah, a lot of the ancient kings loved the big beard as a sign of their warrior prowess and even they would insist that the king’s beard had to be the longest. At least in art, because that suggests that he is the most war-like, the most manly.

So there’s a different role there and so what I have fun with in the book is that there’s a moment in that history of Mesopotamia in about 100 years span, maybe 150 years, there was a dynasty that was sort of trying to play it both ways, where the king would in some cases appear shaved like a priest doing his priestly duties, cuz kings had priestly roles as well. Then at other times, in other places, he would appear with his, as you say, ginormous beard. It’s a little hard to tell whether he actually brought a fake beard or whatever, but it’s certainly in art, in official art, he was shown two different ways depending on what his role was.

Brett McKay: All right, well, we’re going to see this dichotomy show up throughout the rest of Western history, but I think it’s interesting too, you point out, for those who have read the Old Testament and other ancient Near East texts, the act of forcibly shaving a man’s beard off was one of the worst things you could do. Why was that such a terrible offense? Why was it often used as a way to punish a man?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Yeah, there’s a couple famous scenes about that. David’s ambassadors are described as being humiliated that way by a king. I think that by that time, by the time of the Old Testament, the beard had become a symbol of masculine honor and patriarchal pride and as a symbol of that, it could be symbolically used against you. It could be removed and then you’re shamed, publicly shamed.

The David’s ambassadors story, the ambassadors are so embarrassed that they have to stay away from Jerusalem for several weeks while their beards grow again and only then they can feel comfortable enough to actually return to their families and to their homes after this humiliation, so yes, it’s a real thing, because it has become strongly connected with the honor of manhood itself.

Brett McKay: Right and because of that connection to the honor of manhood, you’d often hear ancient people swear by their beard.

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Right, throughout medieval too, that was reintroduced in medieval times by a lot of medieval kings as well, yeah.

Brett McKay: Now, let’s move on to Ancient Greece. What role did the beard play amongst the Greeks?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Well, the Greeks start out by being like the Hebrews. They believed that beards are part of manly honor. They do have a patriarchal society and they honor the patriarch and his great beard. It’s very important and men who have inadequate beards or even were effeminate and shaved them were more often humiliated in public, but something happened during classical times and we’re talking about the 5th century, the time we often think about when we think about ancient Athens.

Something was happening and what was happening was that artists were thinking of how to represent the gods in a new way and they came up with the idea of representing the immortal quality of the gods as youthful, nude men and women. The gods were youthful and nude and the idea is, in a sense, to imitate something that they came up with in their funeral arrangements. They would erect these statues, they started putting up these statues to important men who’d died and these statues were nude, youthful figures.

The idea was to represent immortality. In a sense, think about the human life cycle and when are we most alive, most fully alive? Mature, but not old? That’s what I want to say. Where’s that point in life where we’re mature, but not old, not decayed? They decided that that would be like 18-19 years old, when you’re mature, but not at all old or decayed and that’s the peak of life. So they liked to represent that. No matter how old you were, if you were a 75 year old man and you died, you’d get a statue that looks like you’re 19.

They did that in art more and more. Then when Alexander the Great took over Greece, this is in the 300s B.C., he took over Greece and then conquered the Persian Empire and established Greece as the dominant culture of the whole area. He started to make himself look like the art. Cuz he thought of himself as a demigod. He wanted to look immortal. Luckily, he was young, he was very young, but he shaved his beard, unlike his father and unlike the other Greeks at the time to look like a god. Then everyone thought, “Oh, yeah, that’s a great look.”

Then the Greeks, the Hellenistic Era, the Greeks, after that, all the respectable men shaved and then barbers, the whole profession of barbering took off and then the Romans picked it up later when they adopted Greek ways. So that answers my question that I had originally is “Why did the Romans shave?” Well, they shaved cuz the Greeks shaved. Why did the Greeks shave? They shaved because Alexander the Great wanted to look like a god.

Brett McKay: So it all goes back to that dichotomy of facial hair being sort of earthy, natural man, no facial hair being divine.

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Exactly, there’s your divide again. It’s similar to what was going on earlier, where shaving represents a different kind of masculinity that’s beyond the natural. It’s refined, it’s special, it’s extraordinary.

Brett McKay: You know it’s interesting, that dichotomy. I think whenever the people depicted Achilles, he was often without a beard later.

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Right, later. Earlier he had a beard, in art and then later he didn’t.

Brett McKay: But the exception of the gods with no facial hair, Zeus was often portrayed with a beard still, right?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Right. Zeus is probably the only guy who kept his beard throughout. I mean, even the Greeks couldn’t imagine Zeus without a beard. But funny one that I like to think about is Heracles, or Hercules. Now here’s the He-Man of ancient Greece, the ultimate He-Man. He was a demigod, by the way, he was half god, half human. It was fun to watch him transition in art because here’s the ultimate He-Man, so he keeps his beard a lot longer than the other gods, or demigods, like Achilles, but even he loses his beard by Alexander’s time. Even Hercules, the He-Man of ancient Greece, is beardless.

Brett McKay: Beardless, all right. Continue on with the Romans, you see a lot of the busts of the ancient Romans, most of the Emperors clean-shaven. But then there was Hadrian, and he decided, “I’m going to start growing a beard.” Why did he start growing a beard? What was going on there?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Yeah, that’s what I call the first beard movement. We have 400 years of shaving, where shaving is expected by men of power, and then after 400 years, Hadrian changes his mind and changes everyone else’s mind as well and starts a movement towards beards. He’s inspired by the philosophers, particularly the stoics, and the idea here is the stoics believe that wisdom is following the laws of nature, the universal laws of nature. They’re argument is nature gave man a beard and gave man a beard for a purpose and that purpose was to show that a man is a man, I’m not a woman. If you shave off your beard, what are you trying to do? Are you trying to become a woman, what is that?

Hadrian was one of these Roman Generals, then Emperor who loved Greek learning and really took philosophy very seriously and studied, personally, with some of the top philosophers. No doubt he had these lectures, heard these lectures about beards and said, “You know what? That’s right, I’m a man of wisdom and I’m going to follow the universal laws of nature and I want to model that for the rest of my society.” So he proudly returns to Rome from Greece with a beard and then when he becomes Emperor, that’s it. That sets the tone.

Brett McKay: Yeah, you start seeing like Marcus Aurelius had a beard and he was also a stoic, a stoic philosopher. Let’s talk about one of the most famous bearded men in history who was around the time of Romans. It’s Jesus, Jesus of Nazareth. Today, Jesus is portrayed as having a beard all the time. That’s what we think when we think of Jesus, but you show that that wasn’t always the case during the history of Christianity. Can you talk about the beardiness and non-beardiness of Jesus throughout the early days of Christianity?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Well what we sometimes forget is that the early Christians lived in the Roman Empire and the period that we were just talking about. For a lot of that time … here’s what I got to start with: After Hadrian’s time, shaving comes back in the late Roman Empire and shaving comes back because there’s a sort of a revival of the old style as they tried to keep their empire together and the old style of Caesar and Augustus and so forth.

So shaving is back, if you will. In that time, when Christianity’s really taking off in the Roman world, the early Christians are Romans. They might be Greek speaking, but they’re Roman citizens and their imagery, when they create art and when they imagine Jesus as the Savior, they connect him, quite naturally, with images that they have in their classical culture. Images of Hermes, the Shepherd God, so Jesus is the Shepherd, the Good Shepherd, so they think of Hermes and Hermes is always represented as this young, beardless man.

Or they think of him as Apollo, the god of wisdom and so forth, and so they have all these images of these youthful, beardless immortals and for hundreds of years they presented Jesus in art that way, cuz that’s the visual imagery that they had. It wasn’t till really after the fall of the Roman Empire and the fading away of these old classical ideas and images that Jesus then is reimagined as a bearded man. It’s true that Jesus was almost certainly bearded in real life, but that isn’t why we depict him as bearded. We depict him as bearded because we developed an artistic iconography.

By the way, Jesus always has long hair. Did you ever wonder about that? Why does Jesus always have this long, flowing hair? As well as that beard. That was just part of the iconography of how his image was developed in the early Middle Ages. It’s a holdover, by the way, it’s a holdover from classical times, when long, flowing hair was considered to be part of your youthful vitality.

Brett McKay: That’s interesting. You also point out, in these early depictions, later on, when they’re transitioned from that classical, youthful notion of Jesus, divine Jesus, to the bearded Jesus, there’d be artwork where there would be a bearded Jesus and a non-bearded Jesus portrayed in the same scene.

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: As this iconography is morphing and people are experimenting. “How could we do this?” There was actually a period there where they were both going at the time and artists would be using both. They would typically use beardless Jesus as the Jesus that was on Earth and traveling around and teaching and gathering disciples and performing miracles and then use the bearded Jesus to represent that special last time of his life. The entry into Jerusalem, the passion, the death and resurrection. There really is two Jesus’ when you think about it. There’s the Jesus, the teacher, the miracle-worker, and then there’s the Jesus of the passion and the resurrection.

They would sometimes say, “Well, we could kind of think of him as looking different for those different times.” That got me thinking that artists were really going for is they were creating contrast, so when Jesus is on earth among ordinary bearded men, he’s beardless to represent how different he is. He’s the divine figure on Earth. He’s like an angel who has descended from Heaven, among men. But when he’s ready to enter Heaven, when he goes through his passion and becomes God and not man, and ascends to Heaven, now he’s in Heaven and surrounded by beardless angels and spirits, and here he’s now depicted more typically as having a beard.

I think that’s, again, a contrast so that we’re reminded that although he’s in Heaven, and he’s God, he’s also a man and he has a beard. He’s not an angel. He’s not a spirit in that sense. He still retains his manhood with him even as he sits on the throne of Heaven. I think that’s what they were playing with their imagery and that image of the bearded Jesus in Heaven became kind of the standard look.

Brett McKay: We had this first beard movement during the Roman Era with Hadrian. Then the late Emperor started shaving again to kind of reclaim that kind of classical notion. What happened after the fall of the Roman Empire as we entered into the Middle Ages? Did the clean-shaven look continue?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Well, it did. There was a bit of a breakdown, as you imagine, in cultural and civilization. The church was mostly Roman and Latin-speaking. The church leaders tried to limit the growth of hair. They really enforced short hair. Short, cropped hair, because the New German barbarians that had taken over all around Western Europe were notoriously long-haired and long-bearded. We do have kind of a bearded era here, but the church is resisting, especially in Western Europe, because they want to contrast themselves with the hairy Germans.

That eventually develops into a full-blown anti-hair attitude and that contrast that they start to establish right away in the 500s expands so by the 700s they’re starting to shave the top of their head, that’s what we call the Tonsure, where they make a bald spot on the top of their head. They started that in the 700s and then the monks started shaving their faces as well as shaving the tops of their heads and then that eventually was adopted by the priesthood as a whole and by the 10th and 11th centuries, so you’re getting into more of the middle of the Middle Ages, you have a really strong contrast between clergy and laity.

The clergy are shaving the tops of their heads, shaving their faces but the aristocracy has sort of maintained this Germanic tradition of beards and hair. So you have a real striking contrast between two types of masculinity and what we’ve done is we’ve recreated what happened in the ancient period that I described earlier where the priesthood was shaved and kings, warriors, were hairy. Then there we are again, we’re back to it in the Middle Ages.

In fact, so much so, that the church built it into canon law. That is to say by the 11th century, it was part of canon law. You could actually, if you were a priest and you refused to shave your face, you would be excommunicated, thrown out of the church. They were pretty serious about it.

Brett McKay: But what was funny, you point this out too, is you had the kings, the aristocracy, held on to their beards, or their pagan beards, and then the priests shaving, but the kings would often make fun of the priests as sort of like, “You guys are womanly, cuz you don’t have a beard.” So the priests developed this idea of the inner beard, like, “Hey, we’re still manly. We have a beard on the inside that you can’t see.”

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Right, well it was the great ideological confrontation of the Middle Ages was the conflict of what was called the two swords, the two kinds of power, divine power and worldly power. The sword of faith, the sword of the flesh. That was the great conflict the entire Middle Ages and the Popes and bishops battled with kings for authority and predominance. It was a back and forth thing and both sides would accuse the other of being inadequate.

The church would say “Your beards are representative of your worldliness and of your sin,” so they could throw it back at them. Yeah, so they were very proud of their ‘inner beard’ where they’re growing a manhood of faith and discernment and purity, whereas the world men are lost.

Brett McKay: Right. I don’t know if you ever saw Dexter’s Laboratory, it was a cartoon. There was a scene where Dexter, he’s a kid, he wants to grow a beard, so he puts on a fake beard and this big-bearded guy tells him, “It’s not the beard on the outside that counts, it’s the beard on the inside that counts.”

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Ah, I didn’t know that, that’s great.

Brett McKay: When I read that bit about the inner beard, reminded me of Dexter’s Laboratory. We did the Middle Ages, pretty much a battle between beardiness and non-beardiness, but primarily clean-shaven because of the predominance of the priesthood and the church during that era.

But during the Renaissance, there was another beard movement. So what was going on there? Why did people embrace the beard?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Yeah, and just have to do a preamble to that and that’s that the beard falls away in the 13-1400s because the churchly standard of shaving becomes adopted by the laity as well. We have the triumph of shaving for at least 150 years there and that’s sets us up for another beard movement then in the 1500s and the height of the Renaissance. This is a deliberate reaction against the past. That’s what the Renaissance was. They invented that word. They said “We live in a different time, we’re going to rebirth, that is to say, we’re going to recreate or renovate our society. We are too stuck in medieval unworldliness, we’re too down on humanity.”

The humanists of the Renaissance were more optimistic and enthusiastic about human potential and they were ready to throw off both the spiritual and the actual real power of the church. A new class of worldly merchants, particularly in Italy, were ready to do this and part of that was the reinvention of a new worldly masculinity, embracing positively our natural humanity and rejecting the unworldliness of the church. Part of that was “Let’s embrace beards.”

So it’s kind of similar to what Hadrian had done, with the old philosopher, the stoic philosophy, is “Let’s embrace nature, let’s not reject nature. After all, medieval is about how corrupt nature is.” But the Renaissance is there’s beauty in nature and human nature’s good. So they’re embracing that.

Brett McKay: Yeah, it’s so funny this pendulum that keeps going back and forth.

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Yeah.

Brett McKay: And then into the Enlightenment, shaving comes back again.

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Yeah, well, you know, each time needs a different form of masculinity and the liberation of the Renaissance is all good and well, but for other reasons, not because of liberation as such, but that late Renaissance era, we call it, well, it was off of the Reformation and the age of religious wars, it became a very chaotic time in European. Disastrous time in many respects, the late 1500s, early 1600s were just terrible in social and political terms and so there was in a sense, too much freedom, too much disorder and so royal courts became the center of the effort to restore order and that means social as well as political order.

That meant a new kind of masculinity that needs to be more disciplined, more regulated and more cooperative, more peaceful. Part of that was this elaborate court ritual that was developed. Fancy clothes, fancy stockings, fancy wigs and of course, the eradication of all natural hair. When you wore those big wigs you see in the late 1600s, 1700s, when you wore those wigs, you shaved your head completely. You got to get rid of all your hair and then you put on this massive wig and then you shave off your natural hair so that it’s all controlled and very, very perfect, not unruly nature.

It’s a war against nature. So Renaissance you say “Let’s liberate nature!” And then you’re saying “Oh, too much nature, so let’s control it.” We’re going into a reaction again.

Brett McKay: All right, we had the reaction against that, but then, as we had the first beard movement with Hadrian, then the second beard movement during the Renaissance and then the Enlightenment-

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Well, you could call that the third because we had beards in the Medieval-

Brett McKay: Medieval times, right. But then there was another beard movement during the Romantic Era, which was a reaction against the Enlightenment Era, so I guess the Romantics were embracing nature once again and so that’s why you gotta grow a beard?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Right. Well, yeah, I think so. Romanticism and the beard were accepted by the extreme Romantics, the poets or the liberal-y students, the people were most animated by this exciting idea of liberal romantic ideas that were percolating after the Revolutionary Era of the end of the 18th century. But it never took off, it never became a movement as such because the authorities, the middle classes, and the monarchies and so forth that existed were afraid of Romanticism and afraid of liberal ideas, so they repressed it and it was socially unacceptable.

You had young people, kind of like the ’60s, you have young people espousing this radical new romantic poetry and dreaming about liberation and growing beards and the older, more powerful generation are saying “Oh, this is way too dangerous, we don’t like this. Beards are radical.” If you watch Les Misérables, or you read Les Misérables, there is discussion about the young men wearing beards.

But what happens is that there are a bunch of liberal revolutions led by romantic, bearded young men in 1848 all throughout Europe. France, Germany, Italy, but all those revolutions, if you can imagine like the 1960s, youth actually tried to overthrow the government. It collapsed because they were disorganized and didn’t have any leaders. So all that enthusiastic, political romanticism got kind of crushed in 1848 and 1849. So in the heap of wreckage of that romantic dream, the radical beard is dead and it was no available for all men, it was no longer a threat, so then more and more men experimented with mustaches and maybe longer sideburns and then “Why not a beard, yeah!”

So all of a sudden in 1850s, boom, the big fourth beard movement arrives and men embraced the idea of beards again. The fastest, most immediate, most sudden beard movement ever because I think men had been eager to grow beards for a long, long time and you see the muttonchops and the whiskers, the burnsides going down, down, down the side of the face, but they can’t bear to actually let it grow into a beard because then that would be radical. There’s all this pent up desire of men in the 19th century to grow their facial hair. Then finally when it’s safe in the 1850s, all of sudden, boom, everybody. It’s just like overnight.

I show a cartoon which shows a woman at a train station and these porters are coming to take her bags and they’re all big-bearded guys and she’s just scared to death cuz what in hell, you know, she thought she’s being attacked by thieves, robbers. There’s a sense of almost shock that all of a sudden everyone’s growing beards. It’s really hilarious.

Brett McKay: Right. Now we get some of the most famous beards, they’re very iconic from that period. Abraham Lincoln.

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Right, right, but this is a decade later. He’s a late adopter, would I say.

Brett McKay: He’s a late adopter.

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: He’s a late adopter and he’s very cautious, he’s a, first of all, he’s a lawyer and he’s a politician and these guys have to be very cautious about their public image. People say, “Join the beard movement, Abe.” And he said “Oh, that would be kind of over the top, don’t you think?” He’s very shy and then this little girl writes a letter to him during the campaign and mind you, he’s not campaigning. Presidents didn’t campaign in those days. He stayed at home, but letters come to him and a letter comes from a girl and she says “I saw your picture, your campaign picture, and we all agree that you would look so much better with a beard, you have such a thin face.” He ponders this, and he says “Well, I think it would affectation if I grew a beard now.”

That’s what he says to her, but he does in fact, grow his beard right then and there while he’s sitting home while the election’s going on, so that finally when he emerges after the election and takes the train to Washington, he’s a bearded man. He stops in Northern New York where that girl lived and asked for her by name to come up to him. She came to see him and he said to her “Look, I’ve followed your advice.”

Brett McKay: There you go, the rest was history. We’ve been talking about beards, but what of the mustache? It’s not a full beard, so it’s kind of like a compromise. Is there any cultural significance of the mustache throughout western history?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Yeah, well the mustache has a long, long history with aristocracy and therefore the military. I think the most important thing that developed was in that Romantic Era that I talked about, the Napoleonic Wars at the very beginning of the 19th century. Napoleon’s army and the other armies like the Prussians and the British, that were fighting the Napoleonic Wars, and the Austrians certainly, adopted a style which they thought was pretty awesome.

It was modeled on the look of the Hungarian Hussars. These are Hungarian cavalrymen who were part of the Austrian army, ultimately. They had these awesome look that comes from their history. They had these big bearskin caps, they had these leopard pelt saddles, they had ribbons and embroidery, they were colorful, they were dramatic, they had a curved saber sword and then they had this big, black mustache. The whole look was just awesome, it was original shock and awe, that these cavalrymen would come charging at you and you just run, you know, just at the sight of them.

That was the idea and the European armies adopted this because it was so awesome and this is the Napoleonic Wars. By the end of the Napoleonic Wars, by 1815, all the European cavalrymen are looking like that and their army is drawing up new costume regulations or uniform regulations to adopt to this. Then more units want to do it. They say, “Wow, this is fantastic and we want to look good too.”

So it spreads to the other officer corps. By the middle of the 19th century, now all military units are excited about this and more and more units are permitted and by the middle of the 19th century, it’s actually become regulation in most European armies that all officers and even all enlisted men have to have a mustache as part of their military look. It’s a regulation, you must have a mustache.

In fact, a lot of young men, imagine an 18 year old recruit who’s got not very thick hair, maybe even blonde, and they can’t grow much of a mustache, they had to have a regulation black mustache. If you had a blonde mustache you had to color it. If you didn’t have a mustache you had to put something on, get a fake one because it was regulation, it was your costume. There’s all these complaints in newspapers, like “Oh, we’re not paid enough to get our good-quality fake mustaches.” There’s some fun stories about that.

Then that remains true all the way up to World War I. The French, the British, the Germans, the Austrians, they all required their soldiers to wear a mustache. I have the best accounts from the British Army because the British recruits were complaining that they didn’t want to have to wear a mustache. It was inconvenient to maintain it, to trim it and so forth, and what happened was that during the First World War, the British had to go to the draft in 1916.

When they instituted the draft, they realized they had a morale problem because a lot of the young recruits didn’t have mustaches, didn’t want to grow them and it wasn’t fashionable at the time, it wasn’t their image, they didn’t like it and so the Army, they actually had a court-martial, they started court-martialing men for not having mustaches. Then the higher officials started to rethink this and think “Is this really worth our time to court-martial men for not having mustaches when we’re asking them basically to be cannon fodder on the Western Front?”

They re-examined, re-evaluated and rescinded the order right in the middle of the War because court-martialing was not worthwhile. It coincides with the use of gas masks and so we tend to think that it’s gas masks that made mustaches go away, but that’s not true. You can fit a gas mask around a short mustache anyway. It was more an issue of morale.

Brett McKay: Right, so this begins the 20th century, the movement away from beards, from facial hair and we enter this age of clean-shavenness that we still see today.

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Yeah, well, there are a bunch of reasons that kind of conspire a perfect storm right at the beginning of the 20th century to make this happen. We’re already moving away from beards, the younger generation wants a slicker look and mustaches are actually really the look for a lot of the late 1880s, 1890s. Then by the turn of the century, though, as my story about World War I tells you, mustaches were going out of favor and there’s a perfect storm.

One of the factors is the new interest in cleanliness. It was now understood that disease was caused by microbes, little bugs and these little microbes, they figured out, actually live in hair and they could use the microscope at this time, they look at hair and oh my god, there’s all these microbes on it. Now hair is scientifically dirty, diseased. So removing hair is tantamount to cleanliness.

That’s one thing. Another thing is that this is the age of body-building. Guys like Eugen Sandow are coming along and introducing this idea of muscle building and body-building. That becomes a new way to display masculinity, youth, toughness and vitality. Eugen Sandow, he realizes right away, if you shave your body, you shave your chest and back and so forth, your musculature comes out more cleanly. So it’s muscles versus hair here, and if you’re going for the muscles, you’re going to try to remove the hair and although Sandow had a short mustache like an aristocratic man of his day, eventually the idea of the clean shaven, smooth, muscular, athletic look is taking over.

The third thing is that we’re entering the age of corporate employment and corporations want their employees to represent the company well and look professional and orderly and disciplined and so we’re having a kind of new regulation society that’s not unlike what I talked about with the courts back in the 17th and 18th centuries where we want discipline as our primary. Discipline and reliability, as well as cleanliness as our primary attributes of a good man, a good employee. Companies started to enforce shaving regulations, even banned not only beards, but mustaches as well.

Even from the police forces. Police have this military tradition of loving to look like military. Even today you’ll see that, right? I mean, police love to have a mustache because it kind of has a military look to it. But a lot of police forces back in the early 20th century were telling their men, “Get rid of those mustaches.”

Brett McKay: We’re still in that today, but you are seeing sort of a resurgence of the beard. What’s the status of the beard today? Does it have any larger cultural significance like it did in times past or is it sort of like any other post-modern idea where the meaning of the beard depends on the person or the group?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Yes, the thing about today is we live in a very culturally fluid time. What I’ve been describing all this time is patterns that are established by elites, dominant political groups and they establish a form for themselves and then sort of impose it as the norm for everyone as much as they can, so we have more of a monolithic style and that’s been true all the way up through till recent times.

I think today we’re seeing a more fluid cultural dynamic where there isn’t one type that is enforced on everyone and there’s some good things about that, I guess, but as a historian or as a sociologist, it’s very difficult to say what’s going on because you have all sorts of people following different drummers. You have quite a tremendous variety of attitudes to facial hair, but I will say that there’s a great deal more acceptance in the last 20 years. Very much more. Even Walt Disney company allows workers at it’s theme parks, since 2012, to grow modest facial hair, which was strictly forbidden up till then.

So that shows you that we are becoming much, much more tolerant of facial hair and because we’re more tolerant, I think we’re going to have it. Because men are always going to want at least the option. When people ask me “Are beards here to stay?” I’d say yeah, I think they are here to stay because we’ve reached a high level of tolerance and I think that beards help men develop style of look for themselves and to establish themselves as men and that too, is increasingly difficult in our society where masculinity’s more and more up for negotiation.

Going back to our theme that we’ve followed in this whole discussion. Because beards are associated with nature, and with natural masculinity, it always is a resource there for men to use to stake at least a basic claim to their nature as men, and I think that’s why it’s going to stay.

Brett McKay: Well, Christopher Oldstone-Moore, this has been a great conversation. We really dug deep, but there’s so much more in your book that people can find out more. Is there any place where people can learn more about the book or your work?

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Well, I think the book is widely available now in paperback, so that’s good news. I’ve done a couple things in the Wall Street Journal, and you can even find an interview of me on CBS Sunday Morning and if you Google around, you’ll find some smaller articles where I make some commentary about our present situation if they want to read.

Brett McKay: Well, fantastic, well Christopher Oldstone-Moore, thank you so much for your time, it’s been an absolute pleasure.

Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Great, thanks, it’s been the same for me.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Christopher Oldstone-Moore. You can check out his book of Beards and Men on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/beards, where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out The Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoy this show, have gotten something out of it, I’d appreciate if you take a minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher, help us out a lot. As always, thank you for your continued support and until next time, this is Brett McKay, telling you to stay manly.