On El Capitan in Yosemite National Park, there was a wall that had never been climbed, and that some said would never be climbed. It’s called the Dawn Wall.

But in 2015, Tommy Caldwell along with Kevin Jorgeson became the first to free climb it. That journey was then made into an award-winning film called Dawn Wall.

Today I speak to Tommy about what led up to that historic climb, starting from how he got involved in rock climbing in his childhood. We begin our conversation discussing the different types of rock climbing and why people often misinterpret what “free climbing” means. We then dig into Tommy’s climbing career, including his early success in sport climbing and the harrowing experience of being held hostage by and escaping from rebels in Kyrgyzstan. We then discuss how Tommy responded to losing a finger and getting divorced, and why he decided to climb the Dawn Wall. We end our conversation discussing the years-long process of preparing for the climb and the virtue of what Tommy calls “elective suffering.â€

There are a lot of little, potent lessons here in how to remain persistent and driven in the face of setbacks that apply beyond climbing to every aspect of life.

Show Highlights

- How Tommy got into rock climbing from a very young age

- What climbing was like for Tommy’s father in the ’70s and ’80s

- What Tommy’s parents thought of his making a career out of climbing

- The different types and styles of rock climbing

- The crazy story of being held hostage in Kyrgyzstan

- What Tommy’s life was like after coming back home

- How his career survived the sawing off of part of his finger

- How Tommy’s life and climbing were affected by his divorce

- Why hadn’t the Dawn Wall been climbed before?

- The grueling process of climbing the Dawn Wall over the course of 19 days

- Why Tommy decided to wait for Kevin in order to finish

- What it felt like to actually succeed in the climb

- Why do people elect to suffer? Why are hardships and suffering worth it?

- How being a father has changed Tommy’s goals

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Dawn Wall (award-winning documentary about Tommy and Kevin’s climb)

- Types of climbing

- Chris Sharma

- Beth Rodden

- When Rock Climbing and Terrorism Collide

- How Tommy re-learned his craft after saw

- Kevin Jorgeson

- A Call for a New Strenuous Age

- Baffin Island

Connect With Tommy

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Recorded on ClearCast.io

Podcast Sponsors

On Running. These shoes are so comfortable you won’t want to take them off. And they have a full range of shoes and apparel to power your full day, on and off the trail. Try a pair for 30 days by going to on-running.com/manliness.

Hair Club. The leader in total hair solutions, featuring a comprehensive suite of hair restoration options. Go to hairclub.com/manly for a free hair analysis and a free hair care kit.

Saxx Underwear. Everything you didn’t know you needed in a pair of underwear. Visit saxxunderwear.com and get $5 off plus FREE shipping on your first purchase when you use the code “AOM†at checkout.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. El Capitan in Yosemite National Park, there was a wall that had never been climbed and some said would never be climbed, it’s called the Dawn Wall, but in 2015, Tommy Caldwell along with Kevin Jorgensen became the first to free climb it. Today I speak to Tommy about what led up to that historic climb, starting from how he got involved in rock climbing in his childhood.

We begin our conversation discussing the different types of rock climbing and why people often misinterpret what free climbing means. We then dig into Tommy’s climbing career, including his early success in sport climbing, the horror experience of being held hostage by and escaping from rebels in Kurdistan. We then discuss how Tommy responded to losing a finger … is important when you’re a rock climber, and also getting divorced shortly thereafter, and why he decided to climb the Dawn Wall. Winter conversation discussing the years long process of preparing for the climb and the virtue which Tommy calls elective suffering. But a lot of little potent lessons here in how to remain persistent and driven in the face of setbacks that apply beyond rock climbing but every aspect of life. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/dawnwall.

Tommy Caldwell, welcome to the show.

Tommy Caldwell: Yeah, great to be here.

Brett McKay: So you were one of the first ever along with Kevin Jorgensen to free climb the Dawn Wall of El Capitan. And we’ll talk about what it means to free climb, because there’s something I learned about rock climbing, reading your book, is all types of different types of climbing. Before we get to that moment where you did this, let’s talk about your backstory. When did you get started with rock climbing? And when did you figure out this was going to be your thing for the rest of your life?

Tommy Caldwell: Yeah. Rock climbing was a family trade. My dad was a mountain guide. I was out rope climbing from age three. So when I was young, it was just what we did. I was into it, but I wasn’t hugely passionate about it. I didn’t know that it was going to be a thing that directed my life in any ways, until I was a teenager. I think part of the reason for that was there was no other young climbers when I was young, I was the only one. But when I was a teenager, climbing gyms were starting to come around, there was a competition series that started up. And so I suddenly had a community of friends through climbing, and it was a there was something that I was already good at, since I’d been since doing it since I was three years old.

Brett McKay: You mentioned your father, he’s been rock climbing back in the ’70s and ’80s. And I thought this was interesting, because in the ’70s, and ’80s, rock climbing really wasn’t a thing except for fringe folk. What was the sport back then when your dad was getting started in it?

Tommy Caldwell: If you’re into the history of climbing, it was certainly a thing. There was big, incredible climbs being done, and sort of all the techniques were being pioneered, and so he was in with the forefront of that, realizing that the biggest walls in the world could actually be climbed. But you’re right, it was very fringe. It was in an era where most people didn’t want to do risky things just in general. So rock climbers were out there.

And so my dad took it up, he loved it, he did it until my sister was born. But back then it was way more dangerous than it is now. The the protection systems weren’t what they are now. When my sister was born, he actually quit. He took out bodybuilding instead, for a handful years until climbing got safer again, with the invention of sport climbing.

Brett McKay: I thought that was really interesting, it seem like back then when it first getting started, there was this is sort of really very risk taking ethos. There’s a concern about how you rock climbed, not necessarily if you made it to the top, but if you did it in a certain way, right?

Tommy Caldwell: Yeah, climbers were rebels for sure back then. They’re counter cultural, they’re shutting mainstream society. And so in a world that told them not to take risks, they wanted to take as much risk as possible.

Brett McKay: You mentioned that, that sort of started changing with the invention of sport climbing. Walk us through this for people who aren’t familiar with the different types of rock climbing, because I got confused, I found myself getting confused and had to go back. So there’s sport climbing, what is sport climbing? How is that different from other types of climbing? What type of climbing do you do?

Tommy Caldwell: There’s traditional rock climbing, which back in the ’50s meant that you took little bits of metal and you hammered them into cracks much the way a carpenter would pounder the nail, and you attach carabiners, carabiners were invented back then to these bits of metal and then you climbed up. And so the evolution of that is what we now call traditional climbing, which these days essentially means you’re mostly placing your own protection in the natural features of the rock. And one of the reasons it was so dangerous back then is because it really was just stuff that you’d go to the hardware, go to the junkyard and scavenge and pound them into cracks. So it was hard to test it, it wasn’t all that solid.

Nowadays, we have a whole quiver of really fancy, highly tested tools that we can use to make it a lot safer. But anyways, placing your own gear is traditional rock climbing. Sport climbing is where the first essentionist comes along and drills a line of bolts of the route that stay there permanently. So what this allows is for falling to be really an option you can fall whenever you want on most sport climbs and you’ll just sort of slowly come to a gentle stop at the end of your rope as your blare is bland you. And so it allows you to push the difficulties standards really hard. That’s the simplistic difference of those two aspects of the sport.

Brett McKay: What’s free climbing?

Tommy Caldwell: Free climbing is a terrible term first of all. We need to get the word free out of the whole scene but I don’t think that’s going to happen. But what free climbing means is essentially you are climbing the surface of the rock, grabbing the little edges, twisting your feet in the cracks and that’s how you make forward progress, but you do have the ropes and the equipment there to catch you in case you fall. And so free climbing is different from Aid climbing. When you’re aid climbing you pound those bits of metal into the rock. These days you use cams or nuts or all the fancy tools. And then you attach basically a series of leg loops or a little ladder, nylon ladder, to those pieces of gear and you climb the ladder. So you’re not really climbing the surface of rock, you’re just using this very mechanical method to ascend the wall.

And the reason it’s confusing is because most people think when they hear ‘free’ they think no rope, you fall you die, so that’s free soloing.

Brett McKay: Okay, yeah. That’s where it’s confusing. The difference between free climbing and free soloing. When I hear free, I think no, there’s no ropes at all, but there are ropes you’re attaching yourself as you make progress up the wall, correct?

Tommy Caldwell: Yeah. And free climbing you’re. Although free soloing is a form of free climbing, but you just don’t have the ropes when you’re free soloing.

Brett McKay: Okay. You started doing traditional rock climbing with your dad when he was doing it. In high school you got into sport climbing, correct?

Tommy Caldwell: Yeah, I got into sport climbing and then pretty quickly into competition climbing because it was really the gymnastic form of climbing. It’s gymnastics little body types, scrawny, strong people are really good at this. Sport climbing that’s what I was. Big adventure climbers, more traditional climbers had to have a lot of experience to do it safely. And when I was a teenager, I just didn’t have tons of experience.

Brett McKay: Competition climbing, this is another twist here. So the competition climbing, what does that look like?

Tommy Caldwell: Competition climbing is essentially sport climbing on an artificially built wall where they can control all the elements, they can make the route harder and harder as you go higher. And so the way that the scoring works is usually the person who makes it the highest is the winner.

Brett McKay: Okay, got you.

Tommy Caldwell: And there’s also bouldering, by the way. Bouldering is just on small rocks where you’re not high enough generally to hurt yourself all that badly when you fall. So you don’t use ropes but you just land on the ground. And there’s also bouldering competitions.

Brett McKay: So you were doing this all throughout high school. After high school, what was life for you? Did you decide to throw yourself deeper into rock climbing at this point?

Tommy Caldwell: I wasn’t a very good student, I would say. And as I progressed through middle school and high school, I found myself going on all these amazing trips. First of was my dad but then at some point in high school, I started going on them alone, and I was seeing the world and I was meeting really cool people and I was learning a lot. The classroom was never a great environment for me to learn but traveling the world was a really great environment. And so I got totally addicted to it still within High School. I graduated early from my senior year of high school and went to France for a month. And I also would go on big climbing trips, at every summer vacation.

And so by the time it was time to go to college, I felt like I had found something better that suited me better, the idea of going to college, which would make it … so I had to stop traveling. I had a lot of dread when I had that thought.

Brett McKay: What did your mom think about this? I’m imagining your dad really encouraged this, this passion of yours, but was your mom, “I don’t know about that,” which is a typical mom.

Tommy Caldwell: Well, it was interesting. My father was an educator as a middle school teacher. And so he could see it from both directions, he thought school was very important. But I think both my mother and my father could look at me and see that I had a chance to do well at this sport of climbing. And they also admired the the hand to mouth existence that rock climbing … the full time rock climbing was. They thought that was good for you to go through it. It’s almost going on a pilgrimage or something. So for several years I lived on $50 a month, and traveled around and climbed. And you learn a lot about the world when you do that. And so they were in support of that. They wanted me to live in impoverished lifestyle for a while. I don’t think they ever dreamed that it would have turned into what it is now. I thought they figured I’d go and travel around the world and climb for a few years and then go back to college. But I never ended up doing that.

Brett McKay: That didn’t happen. Well, you also talked about after college, you did a lot of traveling. One of the places you went was France, right?

Tommy Caldwell: Yeah. I go to France almost every year still. So from the time I was just out of high school or even before I graduated from high school until now, I go to France quite often.

Brett McKay: What’s going on there and in the rock climbing world in France?

Tommy Caldwell: When I was younger, it was all about sport climbing. France was the center of the world first sport climbers, and the best, physically, strongest climbers were in France. And therefore the way that the rock forms in France is this big overhanging limestone caves and that’s incredibly jeunesse fun way to climb. And if you want to become a good climber, what’s best is to spend a lot of years building those kinds of strengths. So that’s the reason I went to France. Now that’s still the reason I go to France … back then, still the reason I go to France now is training.

Brett McKay: The other thing you did … experimented with while you were traveling Europe, traveling the world after college was Alpine. This is another type of climbing, Alpine. Is that you alpines, alpining?

Tommy Caldwell: Yeah, alpine climbing is basically climbing on big mountains and snowy environments.

Brett McKay: Okay, so that’s when you probably see the guys with the giant ax, pickax thing?

Tommy Caldwell: Generally, it can encompass a lot of things depending on sort of the style of the alpine climbing you want to do. I generally stay away from the snow although I do. Well, I say that with a bit of hesitation. Sometimes dealing with snow and ice climbing is just a must to get to a lot of the tops of a lot of the mountains that I want to climb. But generally I try and climb the sheer big rock walls, which means I usually have a nice ax with me but I’m not using it that much of the time.

Brett McKay: So in college you’re making a living, rock climbing. How do rock climbers make money? Do you win money at competitions? Is it sponsorships? How does that work?

Tommy Caldwell: Yeah, in my college years, that’s how it started. Since I had been climbing since age three, I could make a little bit of money at competitions. But like I said, that amounted to on average $50 a month. I’d usually spend most of my competition winnings going to the next competition. And I was good at that, but I wasn’t that good at that. There was another gentleman, another friend of mine named Chris Sharma, who basically would win every competition he entered back then. So he made a better living than I did.

But pretty soon I started to acquire a little bit of sponsorship. One of my first sponsors 510, the sponsorship manager had come from the tennis world and she’d seen sponsorship of really young people go badly oftentimes, and so she was really concerned about making sure that I stayed humble. But it really at first it was just getting three pairs of free shoes a year. And then it’s just sort of gotten better and better since then as the sports grown and now there’s legitimate climbing celebrities, which really didn’t exist before.

Brett McKay: So you’ve been traveling the world after high school. In 2000, you decided to go climbing in Kurdistan, what was going on in Kurdistan that made it attractive place to happen? And then what happened to you while you were there?

Tommy Caldwell: That time I was 19 and 20. I was starting to transition out of sport climbing and get into big wall free climbing, climbing really big walls, traditional climbing which is way more adventurous. And my favorite place to do that was Yosemite but you always dream about a place more exotic because Yosemite has some of the best big walls in the world, but it’s right in the middle of Yosemite National Park in California.

But there’s this place in Kurdistan that had rock and walls similar to Yosemite, and it also had good weather. There’s big walls all over the world but some of them are in Pakistan, they’re really high elevations, or Baffin Island and you got to go across [inaudible 00:14:15], and just deal with a lot more. Kurdistan had great weather and big walls. And it was a place that people had been going for probably a decade but there was still a lot of first two cents to be done there. There’s tons of terrain to explore. So that’s what drew us there, but really drew the other members of the team there. I was just the tag along boyfriend. My girlfriend at the time, Beth Rod, was sponsored by The North Face and she got an opportunity to go on this trip, and then she convinced The North Face to invite me along as a rigger for rope, so I could put up rope so the photographers can get around and take photos to advertise The North Face equipment.

Brett McKay: But then while you were there climbing, you guys became hostages of some rebels in the area? Was there a war going on? What was happening there?

Tommy Caldwell: Yeah, it turned into a war that year. We were climbing our first wall of the trip, so we were climbing this 2000 foot wall called the Yellow Wall, and these ones are big enough that they take multiple days, so we’re sleeping in our portal ledges which are hanging cots 1000 feet up the wall. This one morning when a rebel insurgency called the Islamic Movement, it was Uzbekistan, moved into the valley. And the political situation is a bit complicated, but some ways it boils down to opium trade, but sometimes they try and traffic drugs over these remote high mountain valleys because there’s not much in the way of border patrol back there. And that part of Kurdistan is there’s borders everywhere. Borders of Uzbekistan and Kurdistan were both within 30 miles of us. And so it just so happened that they came through this valley that we were climbing in, and they saw us up on the wall, and they came to the base of the wall with their long range assault rifle. At first at dawn and they started shooting up at us, and they were pretty good shots. They were able to get bullets right between our two portal edges, which were about four feet apart. So we knew we had to come down.

Brett McKay: How long were you held hostage for?

Tommy Caldwell: Six very life changing days. The whole situation elevated drastically. Once we got down we were taken hostage and then just a few hours later the Kurds military moved in the valley and a full on war broke out around us. It was intense in a way that I couldn’t even comprehend before going on that trip.

Brett McKay: How did you all escape?

Tommy Caldwell: The short answer is we ended up pushing one remaining captor off a cliff and running to Kurdie military outpost which was about six or eight miles down the valley, but obviously a lot led up to that six days. When the Kurdies military showed up, we had to abandon all of our food and warm clothing and run as captors of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and hide for those six days, and progressively got weaker. We were pretty close to succumbing to hypothermia and so got quite desperate.

But our captors were almost worse off than we were in a way because they had to abandon all their freedom warm clothing and we’re climbers and this is really steep terrain. So we were comfortable on the terrain in a way that they weren’t.

Brett McKay: How did this change your climbing career? This really traumatic experience.

Tommy Caldwell: It change it in a lot of ways. Like I said, going on into the trip I wasn’t a well known climber, I was just the tag along boyfriend. We got back from Kurdistan and then Beth, my girlfriend at the time, we bonded very heavily. And we also were trying to find a way to cope with the trauma of what we had been through. So we climbed together and we were fueled, and I would say me more than her possibly by this sort of deeper, darker, almost stronger force. Climbing had been my safe place, it had been what had brought me joy for my entire life. And so when I was in a place where I was feeling all mixed up in the world, that’s where I returned to, I went to El Cap.

But sensations like fear and pain had been totally reset. And I pretty quickly realized that if I can go big wall climbing and not really have to worry as much about fear and pain, I’ll do way better. And so it went from this devastation to empowerment to sort of curiosity about the limits of my chosen passion, which was big wall climbing, and so it really jump started this … a career doesn’t seem like the right word, but jump started what my life is today.

Brett McKay: Well, then what happened a few years later? This was devastating. You accidentally sawed off your index finger because you guys were building a house together.

Tommy Caldwell: Yeah, that was only a year, or less than a year after Kurdistan.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and fingers are really important for a rock climber.

Tommy Caldwell: Yes. It was a time in my life when, the only real future that I knew was rock climbing. And I was starting to make a living at it. I was like this is something that I could actually support a lifestyle doing. And then I sawed off a finger and just in a home remodeling accidentally, I was using a table saw, not that experienced with using a table saw and ended up chopping it off.

Like you said, I think everybody in my community except for maybe Beth and maybe my father, “He’s done.” Climbing is so much about finger strength, and if you lose a finger, it’s over. But I had this pretty pivotal moment in the hospital. I was in the hospital for two weeks, I went through three surgeries, and they just didn’t work. And in the end, the doctor came in sat down next to me and he said, “Tommy, we tried everything we can, your finger’s essentially dead, we’re going to have to remove it permanently. And you should start thinking out about what else you want to do in your life, because you’re not going to be able to be a professional climber anymore.” The doctor was actually a climber himself.

He stood up and left. And then I remember Beth looking at me and just being, “He has no idea what he’s talking about.” That was really the right thing. I don’t know if it’s just inherently built in to me, but when I have these big challenges with these big setbacks, they turn into fuel. And so Kurdistan was that, but my finger in a way was that too. I wanted to prove the doctor wrong, I wanted to prove to myself that I still had it. And so I got way more scientific and serious about the ways that I climbed. And almost even more so than Kurdistan, it was the biggest leap in, and sort of how good I became as a climber.

Brett McKay: Did it take you a long time to get back on the wall? Was it just a few weeks after the last surgery? Or, did it take a little bit longer?

Tommy Caldwell: I was climbing within a week of the last surgery but not well. I think I had very low expectations, so it was really easy to exceed those expectations. So my first day climbing, I was, “Oh, I’m actually climbing okay.” And then, a month later I was getting close to being able to sport climb on his heart of roots as I had with all 10 fingers. And then six months later, I was doing things that were harder than I had ever done. It was a pretty powerful time of life.

Brett McKay: And then a few years later, another setback, you married Beth in that time, but then your marriage ended. Did that affect your climbing? Did you go into a funk or was it one of those moments again where that became sort of fuel for your climbing?

Tommy Caldwell: At first, I certainly went into a funk and all these setbacks, went through evolutions, but I think, essentially, we had bonded really, really heavily through Kurdistan, and I think Beth needed to escape that, that very deep bonding, and so she left me in a way that pretty heavily devastated me. But like I had learned through a lifetime of encountering these setbacks, it just made me double down at it. Made me look at the things that I sort of appreciate and enjoyed the most in the world.

And really, the main thing that it did, it made me try and find the next big huge thing that would cause … that I would have to change as a person, to do. Like a climber, that I would have to become so much better. And she is the person to do, because I wanted to get lost in that process. And so that was the infancy of the Dawn Wall.

Brett McKay: The Dawn Wall. So tell us about the Dawn Wall. Why hadn’t this part of the mountain never been climbed before?

Tommy Caldwell: So El Capitan for a lot of years was only climbed by aid. And then in the ’70s, a few people figured out ways to climbed free, to build a free climb it. When I started getting into climbing out on El Cap, that’s what I was doing, is I was free climbing all the existing routes. But other it’s at that time I went up these pretty obvious crack systems to train climbers, how you could look from afar and imagine that those walls could be climbed. But there is this one aspect of that just looked sheer, and blank, and it didn’t look there was really anything in the way of crack systems.

And since I’d spent so much time on the wall, probably more than anybody at that time, I was maybe the one person that knew that on this rock that from a afar looks totally blank, sometimes edges form, and if you train yourself just right, you can start to learn to climb from one to the next. And so it just became this giant puzzle. I actually spent almost a year swinging around and trying to piece together this huge puzzle and build the belief that it was possible.

Brett McKay: So it took you a year to have that sort of investigation and preparation before you actually started climbing? Or, was it more than that?

Tommy Caldwell: It was on and off for a year and I was climbing on it. The holds that you grab are so tiny, a lot of them, you have to actually mark them with a little bit of chalk to even know that they’re there, they’re almost too small to see with the naked eye very easily. So I was mapping out the sequences and doing that. By myself I had developed these ropes, soloing techniques, to be able to go up there, and try the individual moves. I knew that if I could do all the individual moves, then the route was theoretically possible.

And so after a year, I got to the point where I was able to … I found a path where I could do all the individual moves, but then piecing them together for 3000 feet was the real daunting part.

Brett McKay: And then how did you sync up with Kevin Jorgensen to do this?

Tommy Caldwell: I actually gave up on it. I pieced it together, I was like, “This is a route, somebody will climb this someday, but it’s just ridiculously hard. It’s so above and beyond anything I’ve done before that I’m never going to be able to do it.” I’ve worked on film projects throughout my career. The main filmer that I worked with Josh Law from Bigger Productions called me and he knew what I was seeking on the Dawn Wall. And he said, “Okay, well, if you’ve given up on it, we should make a film about this, so we can put it out there to the next generation,” because he felt pretty strongly like this was the future, this would be a big deal in the future.

So I went up with a crew of four people and spent a week climbing on the individual sections, sleeping up on the wall with the crew, and making this film to show off the beauty and the wonder of that route. And then they put out a video called Progression, they do a tour called the Reel Rock Tour, and it’s always the cutting edge stuff that’s going on in climbing. And that video showed up in the Real Rock Tour for one year, and Kevin saw the video. And at the end of that video, I make this call out. I was like, “I don’t I don’t know if I’m ever going to do this, but I wanted to put it out there for the next generation.” And Kevin was looking for something new. I think he’s heard that and he’s like, “Well, I’m the next generation.” So he called me up.

At first I wrote him off because I was like, “He’s … ” Kevin had never climbed anything that. He was a boulder, which means he rarely climbed more than about 30 feet off the ground. But since he was such a good boulder, he could do the individual moves better than I could. So I agreed to go up there and see how it went with him.

And first, I was just sort of mentoring him, but I thought … He inspired me to join him back on the project. And that started the six years partnership that it took to actually get it done.

Brett McKay: Wow. And then when you guys finally decided to make the ascent, how long did it take to go up the wall?

Tommy Caldwell: 19 days. And we tried several times, I think we tried three times to do ground up assess. Because most of our time was just spent aid climbing around on the wall and trying the individual moves and piecing it all together and figuring out how to live up on the side of a big wall and climb really hard for long periods of time. And then once we get all the moves wired into our brain and then our memory, then we would make these ground up attempts. And we failed miserably twice. And then our third time is the one that worked. We actually made it and took 19 days.

Brett McKay: Walk us through, how do you feel whenever you accomplish it? Do you feel awesome? How long does that feeling last?

Tommy Caldwell: The feeling was all over the board. As we were climbing for those 19 days, it was very dramatic, because I had managed to get through the hardest section of the climb. And I got to a point where I knew success was pretty much inevitable, I could climb to the top relatively easy, but Kevin was failing. And the way that you do these climbs is you break them up into rope lengths or what we call pitches, and there was 32 consecutive pitches. And so to constitute a successful ascent, you just have to climb each of those 32 pitches in a row, but if you fall you can return back to the beginning of that pitch. You don’t have to go all the way to the ground.

So about halfway up, Kevin started falling on one of the pitches, and he cut his fingers quite badly and I remember grabbing onto these little, little tiny razor sharp edges, so once you get little cuts in them, things tend to downward spiral. It was middle of winter, we realized that to climb this route, we had to climb when the temperatures were absolutely as cold as we could find because your skin’s a little bit harder, the rubber on your shoes is a little bit harder. You don’t sweat at all. So we ended up climbing in the middle of winter. But the problem is, these big storms can roll in. So when Kevin was failing, it felt quite urgent, because if the storm roles in, ice fall comes down, you have to basically run away, and it will fail again.

It just turned into this dramatic thing. And then the news caught hold of it and it went big in the New York Times, and there’s all these news trucks on the valley, it was just very surreal thing. I think I knew that success for me personally, could happen if I decided not to wait for Kevin like a week before we topped out. But luckily I did wait for Kevin. And some of the glory moment was on the last day where we camped a few hundred feet from the top. It was just me and Kevin, and then our one filmer for Brett Law, Josh’s brother. And we were just sitting there when the sun came up. And we knew that we’re going to make to the top and it just felt incredible because it wasn’t distracted.

When we got to the top it was just a circus. There was like 50 reporters there, and I just wanted to hang out with my wife, my kids, and my life became very different, very quickly after that.

Brett McKay: What have you done after that point?

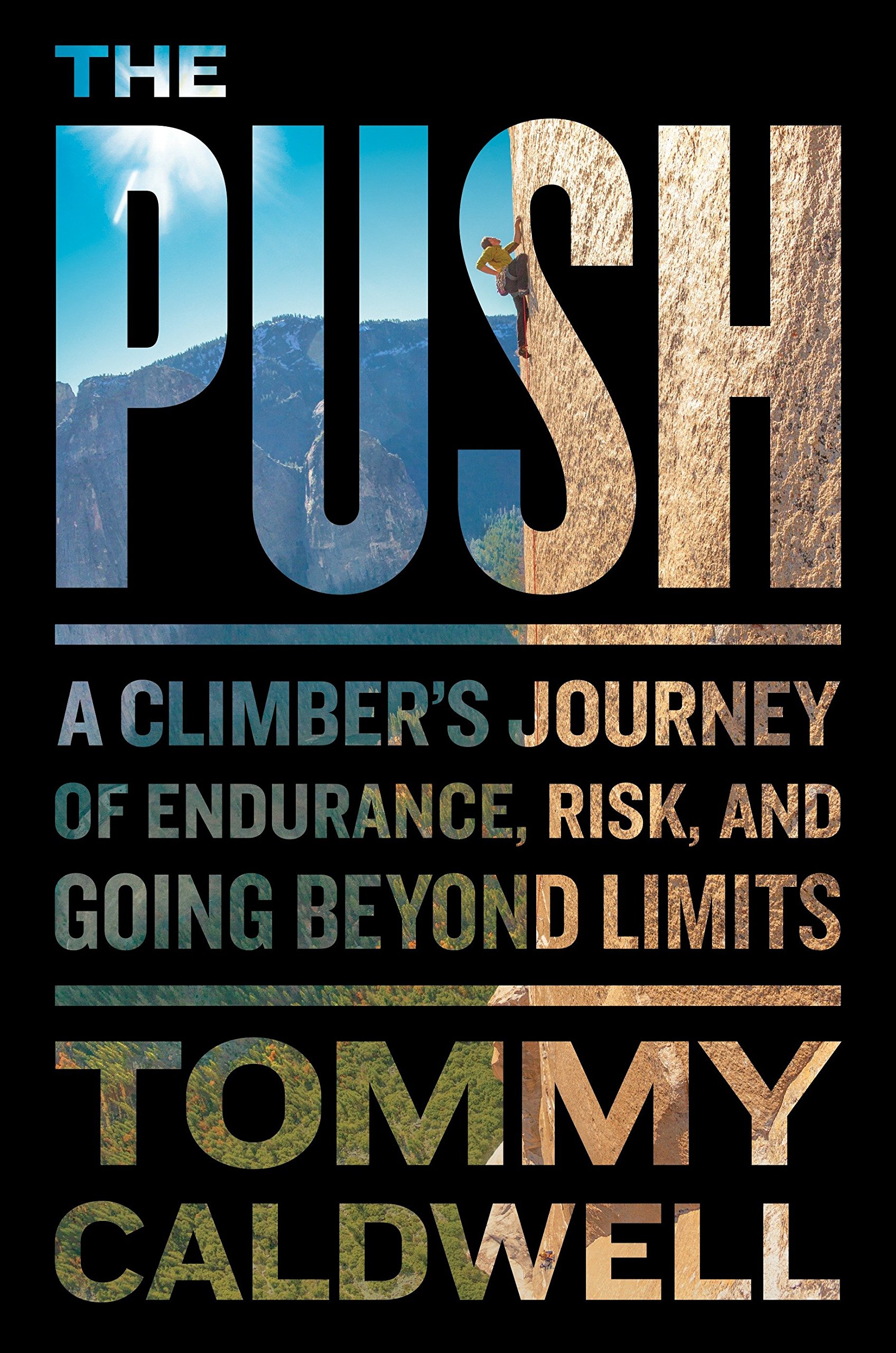

Tommy Caldwell: I’ve spent the last four years now, I guess it’s been just over four years since we climbed the Dawn Wall. I guess living this new life, I wrote a book, the movie, The Dawn Wall came out not too long ago, it’s available on iTunes now. So taking all that video footage and putting it together into a proper movie took three years. I’ve been doing other climbing trips as well in that time. But I would say I spent a lot more time at the office working on the computer, doing interviews, doing film festivals, doing book events, I travel.

Brett McKay: One thing I love from your book is you talked about this idea of elective suffering. What do you mean by that? And why do you think choosing … Why do you think people should elect to suffer?

Tommy Caldwell: I think that most people can relate to that. Because things that are valuable don’t come easy. And so, if you find a way to find joy in the midst of suffering, that’s a good thing. But I guess elective suffering, really speaks to creating hardship on purpose, because you know it’s going to change you as a human being. And I feel my story and its essence is about unintended hardship, but really, since I figured out a way … I kind of got addicted to hardship in a way, so it became elective suffering. Climbing the Dawn Wall was incredibly hard work and it put us through a lot and so therefore, it created this life that was elevated or at least I felt that way. I’m still back to addicted to that. Like everybody’s got these big dreams or these big goals and usually what keeps them from doing that is the suffering component, it’s just too much work in the end. But if you can find a way to enjoy that process, to really truly enjoy that process, that’s the elective suffering.

Brett McKay: Are there any unclimbed walls still out there in the world that you have your eye on? Or, have they all been climbed?

Tommy Caldwell: There are lots of really really amazing big walls. Most of them are in remote locations that require big expedition travel to go to. Like this place that I’ve always wanted to go, I haven’t made there yet, Baffin Island. Baffin Island is 100 Yosemite’s but you got to deal with our the Arctic environment and polar bears, and ice break up, there’s a lot of them, right on the ocean. They’re just remove and therefore more dangerous than I’m willing to accept right now because I’m a father.

I always aspired to go more and more into that big adventure travel world, but I started noticing that all my friends that were doing that were dying. And so for me, that just doesn’t feel like an option. So I keep finding myself going back to Yosemite, because Yosemite has these big really inspiring routes. But the rock is so good and I’m experienced enough that I don’t feel it’s that dangerous. It fulfills this need to sort of explore when these big incredible objectives are available in Yosemite. It’s not new walls per se, but it’s new routes on these walls. And so I find myself continually going back there every year and finding new big routes in Yosemite.

Brett McKay: Well, Tommy, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about what you do?

Tommy Caldwell: They can pick up my book, The Push, on most local bookstores but also Amazon is a good way to get that or you can see the Dawn Wall movie, which won Audience Choice at the South by Southwest Film Festival. It’s gotten pretty big, the movie’s really good. Like 100 minutes snapshot of my entire life. Man, people absolutely love it, so you can get that on iTunes. And I think in a couple weeks, it’s going to be on Netflix as well.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well Tommy Caldwell, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Tommy Caldwell: All right, thank you so much.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Tommy Caldwell. He’s the first person to free climb the Dawn Wall on Yosemite’s El Capitan. He’s written about that experience in his book “The Push; Climbers Search For The Path.” There’s also a documentary about it and you also find out more information about his work at his website tommycaldwell.com. Also check out our show notes aom.is/dawnwall, where you find links to resources, we delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM podcast. Check out our website artofmanliness.com where you can find her our Podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles rewritten over the years about how to be a better husband, better father, a better all round man. Also if you haven’t done so already I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher, it helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think will get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay. You not only listen to the AOM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.