If you call someone a dirtbag, you might be insulting them for being dishonest. Or, you might be describing their lifestyle — their pursuit of an outdoor passion at the expense of more mainstream options and commitments.

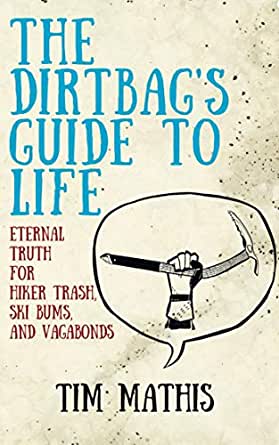

If you’ve ever dreamed of being a rock climber living in a van or becoming a rafting guide, thru-hiker, world traveler, or some other kind of nature-loving, adventure-seeking wanderer, my guest has written a handbook for making it happen. His name is Tim Mathis and he’s the author of The Dirtbag’s Guide to Life: Eternal Truth for Hiker Trash, Ski Bums, and Vagabonds. Tim and I begin our conversation with what it means to be a dirtbag, the origin of the term amongst the early rock climbers who explored Yosemite in the 50s and 60s, and why Tim thinks the lifestyle embodies a countercultural philosophy. Tim then offers a window into why others might adopt this approach to life, by sharing his story of how he personally became committed to dirtbagging. From there we turn to the brass tacks of embracing a life centered on outdoor adventure and exploration, beginning with how much money you need to make it happen, and the kinds of jobs and careers that are conducive to it, including, perhaps surprisingly, the field of nursing. Tim also shares how he responds to criticism that being a dirtbag isn’t a responsible way to live. We then discuss the effect dirtbagging can have on someone’s relationships, and whether this lifestyle is viable if you have a spouse and kids. At the end of our conversation, we discuss how, even if you’re living a more freewheeling lifestyle, it’s important to have a sense of meaning beyond traveling around and doing cool stuff, and the three elements that go into finding that kind of meaning, which apply to dirtbags and non-dirtbags alike.

If reading this in an email, click the title of the post to listen to the show.

Show Highlights

- Where did dirtbagging come from?

- How Tim became a through-hiker

- Why do people become dirtbaggers?

- Why dirtbagging isn’t as expensive as it might seem

- The careers of dirtbaggers . . . are perhaps more varied than you’d expect

- True responsibilities vs. social expectations

- What do relationships look like with a dirtbag lifestyle? What about kids?

- The dark side to the dirtbag lifestyle

- How Tim found some more meaning with his life

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Valley Uprising

- Let My People Go Surfing

- How to Travel Around the World With Just a 20lb Backpack

- How to Take Care of Your Feet on a Hike

- Lessons in Persistence From Tommy Caldwell

- Exploring Life’s Trail, Literally and Metaphorically

- 5 Unexpected Skills Needed on an Ultrabacking Adventure

- The Complete Guide to Hiking

- Hiking With Nietzsche

- How to Hitchhike Around the USA

- Nat Geo article on death by suicide in ski towns

- Finding Fulfillment in a World Obsessed With Happiness

- Against the Cult of Travel

Connect With Tim

Tim’s website

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. If you call someone a dirtbag, you might be insulting them for being dishonest, or you might be describing their lifestyle, the pursuit of an outdoor passion at the expense of more mainstream options and commitments. Have you ever dreamed of being a rock climber, living in a van, or becoming a rafting guide, through-hiker, world traveler, or some other kind of nature-loving, adventure-seeking wanderer? My guest has written a handbook for making it happen. His name is Tim Mathis, and he’s the author of The Dirtbag’s Guide to Life: Eternal Truth for Hiker Trash, Ski Bums, and Vagabonds.

Tim and I begin our conversation on what it means to be a dirtbag, the origin of the term amongst the early rock climbers who explored Yosemite in the 1950s and ’60s, and why Tim thinks the lifestyle embodies a counter-cultural philosophy. Tim then offers a window into why others might adopt this approach to life by sharing his story of how he personally became committed to dirtbagging. From there, we turn to the brass tacks of embracing a life centered on outdoor adventure and exploration, beginning with how much money you actually need to make it happen and the kinds of jobs and careers that are conducive to it, including perhaps surprisingly, the field of nursing.

Tim also shares how he responds to criticism that being a dirtbag isn’t a responsible way to live. We then discussed the effect dirtbagging can have on someone’s relationships, and whether this lifestyle is viable, if you have spouse and kids. And at the end of our conversation, we discussed how even if you’re living a more freewheeling lifestyle, it’s important to have a sense of meaning beyond traveling around and doing cool stuff, and the three elements that go into finding that kind of meaning, which apply to dirtbags and non-dirtbags alike. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/dirtbag.

Alright, Tim Mathis, welcome to the show.

Tim Mathis: Yeah, thanks, Brett. It’s good to be here.

Brett McKay: So you are the author of a book called, The Dirtbag’s Guide to Life: Eternal Truth for Hiker Trash, Ski Bums, and Vagabonds. So I think most people, they’ve heard the term dirtbag, but they heard as a pejorative, like, “That guy is such a dirtbag.” But this book’s about… Dirtbag is actually a lifestyle. For those who aren’t familiar with dirtbagging, what does that entail?

Tim Mathis: You’re right, the term dirtbag, I think it initially originated as sort of pejorative, and even in the way it’s applied, in the way that I use it, it was initially applied to people in a pejorative way, and they’ve embraced it and run with it, as so often seems to happen. But yeah, the basics, I think people who are familiar with outdoor sports in the outdoor community will have heard the term dirtbag as a reference to a certain type of person in the outdoor community. They’re the type of person who I think traditionally, if you thought about these people, they are the people who basically quit their jobs and go pursue their sport. So, they’re either climbers who quit their job and go live in Yosemite for the summer, or they’re through-hikers who go hike the Appalachian Trail or the Pacific Crest Trail, keeps a low-level bartending jobs or something in between hikes, or they’re like the ski bums, or they’re the rafting guides. These people get referred to as dirtbags a lot. They’re the people who I guess, pursue their love of the outdoors, and their love of a particular activity in the outdoors at the expense of other aspects of their life, whether that’s their jobs or their career paths, or money, or whatever it might be.

I also think one of the things I talk about in the book, as you mentioned, it’s sort of there’s a lifestyle element to it, but I also think that one of the things that I came to realize as I was writing the book is that it’s also… I think it’s fair to label it as a counter-culture. It’s like a group of people who are rejecting a lot of the mainstream ways of pursuing life in favor of a different path, so they’re in the tradition of lots of other types of counter-cultures like the hippies and the punk rockers, and those sorts of things. These are people who are forging their own path and rejecting the traditional options that are offered to them.

Brett McKay: And what’s the history of dirtbagging? Is this a recent phenomenon is this something that goes back a couple of decades.

Tim Mathis: Yeah, well, it’s pretty interesting once you start digging into it. One of the questions I was trying to answer with the book initially was, Where did this concept come from? And who were the first dirtbags? How long have people been using this term in this sort of way? There actually is a… There is a pretty… You can piece together the history of it, the first people who it seems like were really referred to in this way and embraced it were a group of climbers in Yosemite in the 1950s and ’60s. There’s actually a decent… Actually, a really good film about these guys called Valley Uprising that really tells the genesis story of this dirtbag community that I’m talking about. These were essentially hippies in the ’50s and ’60s, they’re like the credo, hippie, like Jack Kerouac types who were very intentional about the fact that they were disappointing their parents by not pursuing a real job but were going and living in camps in Yosemite and climbing all the time.

And these are rock climbers and these guys put up a lot of the original routes in Yosemite. They’re legendary in the climbing community, it’s guys like Royal Robbins and Yvon Chouinard, who is the founder of Patagonia, is another guy who’s associated with those early stage dirtbags. In his book, Let My People Go Surfing, is another forage and story about how this dirtbag culture was developed, and his story is really about a trip to Patagonia and pursuing surfing at the expense of other things, and just the beauty in that. It’s a term that we’re not really sure… I’m not really sure anyway who used the term first. Actually, Yvon Chouinard gets credited with it. There are some quotes from early on in the ’60s or something, where he mentioned that these guys in Yosemite get called dirtbags, and they are a bunch of dirtbags, but probably he wasn’t the first one to use the term, but he was one of the people that definitely was influential in the concept spreading.

So there’s climbers… I think a lot of times climbers will be protective of the term, like it’s they own it or whatever, but as times going on in the last couple of decades, really. Well, I mean, it’s been 60 years now I guess really, people from all different aspects of the outdoor community have lived the same lifestyle, I guess. My introduction to dirtbagging has mostly been through through-hiking and trail running, and through-hikers are consummate dirtbags because they’re a people who… To hike the Pacific Crest Trail or to hike the Appalachian Trail, it takes five or six months for a lot of people, so you have to organize at least one year of your life around it. So these are people who quit their traditional path and pursue this love of the outdoors. And people do that, you find across all the outdoor communities, there’s dirtbag mountain bikers. Rafting guides are classic dirtbags, I think. They’re another group of people that primarily they work summers, and sometimes they chase summers around the world. Ski bums are also the classic dirtbag types. They’re a people who are just chasing powder, chasing winter around the world. They’re organizing their whole life around this outdoor sport.

So what I think has happened is a lot of people with similar interests pursuing it in a slightly different way have all developed a similar approach to life for similar reasons, and I think the term dirtbag has gotten applied to all of them at different times. And in writing the book and looking at these different groups, the thing that I came to was the idea that this is, really, it’s best if you think about this as a counter-culture, even if a lot of the people in the counter-culture wouldn’t necessarily identified that themselves.

Brett McKay: Well, so you mentioned you, you’ve become a dirtbag yourself. You were in a climb where you got into the counter-culture of dirtbagging through through-hiking. When did this happen? Why did you decide… Was it sort of like a Saul on the road to Damascus? Instant conversion? Or did you slowly find yourself becoming a dirtbag?

Tim Mathis: Yeah, that story is as long or as short as you want. I think there’s a couple different things I would say about it. One is that I think that the outdoors and just kinda playing outside has always been important part of my life. I grew up in the country in Southern Ohio, so very much farm country, not the kind of place you would associate with rock climbing or mountain biking or hiking. Well, I mean, we did a little bit of hiking, but not a lot of this sort of West Coast, rich white people type outdoor activities, but was a lot of the plunging creeks and shooting guns with my friends, and we did some hiking, we did some camping, we did some fishing, all those sorts of midwestern outdoor activities were always a big part of my life when I was young.

And then an important genesis point was, we went, my, at the time fiancée, who’s now my wife, did an exchange program in Australia for a quarter during her undergrad, and I went over there and we basically dirtbagged around for about a month while I was there on the east coast of Australia, and that was very much an eye-opening experience for a kid from a small town Midwest that the world’s a really big place and there’s a lot of cool places in it, and you could spend a whole lifetime exploring. So that planted the seed. After that, we did a lot of different things. We moved to New Zealand after we graduated from college, and we spent a few years there and did a lot of hiking, and I did a Master’s degree that was focused on science and religion that was really focused in a way. I wasn’t thinking of it in these terms at the time, but in a way it was focused on this, it was really the question of how people find meaning and purpose in nature and the world around them.

So that, I kinda got into it academically. We got into trail running after we moved back to the States after the degree. That was in 2005, we moved to the Seattle area and we got really into trail and ultra running. Ultra running itself is basically a lifestyle because in order to train for races that take all day, you basically have to spend all your time that you’re not at work running. So, we’ve gotten in a lifestyle of it there, and then I think the story I wanna tell though is that genesis moment when I connected the dots that this was a thing I was focusing my life on versus just a thing that doing for fun. In 2015, is when the dots connected. We’d gotten into trail running and had been pretty seriously into it for about five years by 2015, and we’ve done a lot of really long races. We’ve done 100-mile ultra marathons and a lot of self-supported stuff, and we’re just looking for next steps.

And in the trail running community, there’s a lot of overlap with the through-hiking community. There’s a lot of people who love being outside and love going long distances so it’s not surprising that you also meet people who’ve done that for extended periods of time on these longer through-hikes, like the Pacific Crest Trail or the Appalachian Trail, or the Continental Divide Trail, or what have you. And so we met a fair number of people who’d hiked the Pacific Crest Trail, and then it planted a seed for us, and in 2015, just our lives lined up in a way that we were at a place financially where we could quit our jobs. We were both nurses so career stability was not really that much of a concern. A great thing about nursing for this kind of lifestyle was you quit a job and come back to another one.

So anyway, in 2015, we decided that we were gonna take the leap and quit our jobs and go hike the Pacific Crest Trail. We’ve never done much longest since hiking like that, and the longest I think we’d been out was probably three or four days before that, but this was a great next step for us after feeling like we’d done our thing with ultra running and looking for what’s next. We got our schedule together and we were gonna leave for the trail in April of 2015, and everything was all prepared, was heading towards my last day at work, and I got a call one day while I was at work that my dad had collapsed at his job, and had gone into a seizure. My dad is not someone who’d ever had seizures, he was 62 at the time, and he never had a seizure in his life. And if you know anything about brain health, if you haven’t had seizures early in life and you start to have them later, it’s a really bad sign. There’s essentially no good reason that that would happen, it’s likely either a stroke or a tumor or something really serious. It took him hours to get him out of the seizure.

In the meantime, I was planning flights back to Ohio, which is where he was at the time. Long story short in that bit, we found out that he had glioblastoma, which is a really… It’s both the most common and the most malignant type of brain cancer. It’s a cancer that there’s no remission for, it’s universally fatal. There’s some treatments that can stretch out life, but there’s no cure for it. So, that was obviously a major shock that came at the same time that we were planning this trip, it was within weeks, so when we were planning to leave. And so, we were thrown into this crazy, “What do we do now?” kind of mode. Essentially, what happened is, my dad ended up getting a surgery that the doc said was largely successful, they were able to get most of the tumor out, they felt good about his prognosis, it was in a part of his brain that wasn’t required for life-sustaining functions. You need your brain, no matter which part of it, you need it, but there are some parts that you can survive without and so you can. His was in the front.

And so he got the surgery, the docs felt good about his prognosis, they felt like he was gonna be around for a couple more years. I’ve been consulting with him and my mom, we decided that we were gonna continue and go on to the PCT, they were pretty insistent on it, actually. They’ve always been part of this. My parents were very supportive, they’ve always been part of this process, and so they wanted us to go, they didn’t want us to cancel plans for them, they want us to go, so that’s what we did. So we started the trail and they actually took us to the start, and it ended up being really, the last time that I saw my dad healthy, this was about, like I said, this was about a month after his initial diagnosis, and so just a few weeks really after his surgery, but he was up and well enough to drive us from Las Vegas to the Stardust. But anyway, they dropped us at the start of the trail and we did the normal stuff you do on a through-hike, which is realizing how hard it’s gonna be, getting into the grind, getting into the rhythm of sleeping outside every night, figuring out how you re-supply and you keep yourself fed and watered.

We walked through the California desert, and we were in the process keeping track of what was going on with my dad and things were progressing, but they didn’t feel great. He got through his chemo alright, he had some nausea and stuff, it wasn’t too terribly bad, but he was doing the things you would expect during chemo and radiation. He was sleeping a lot, he’s feeling tired, feeling miserable, but generally things looked like they’re supposed to look. We talked to mom and she’d always be noncommittal about how he’s doing, and he would put on a brave face when we had talked to him as well. So we just kept plugging along and keeping track of what was happening at home with them. The day after we hit the midway point for the PCT… The PCT runs through the mountains so very frequently you don’t have cellphone reception. So the day after we hit the midway point, we were walking towards the highway where we were gonna hitchhike into town for our next re-supply and we’d started… We turned on our phones ’cause we’re getting back in cellphone service and just started getting all these dings, and that’s actually pretty ominous in that situation ’cause we’d usually get one or two messages and in this case, there’s 15 or 20 there.

It was immediately just had this sense that things were off. Essentially, there was a series of text and voice messages telling us that the cancer was back, and the doctor suggested another surgery and they were wanting to let us know, and I think in that time when that series of text came in, I just knew that our trail was over, that was sort of the sign when the cancer came back that we were gonna get off trail, so we hiked away into town, we made a series of phone calls, we talked to the doctors, and I think as a family decided that it didn’t make any sense to put dad through another surgery because the surgery wasn’t gonna… It was gonna make the quality of his life worse, he might not make it through it, and there was zero chance that it was gonna solve the situation. It was at best gonna give him another month of life or something like that. That would have been miserable and he would have had a healing brain during that period, so he wouldn’t have been even conscious during it.

So, we basically made the decision that we were not gonna treat and we made our way. This was in… We were in Central California, so we made our way from Central California to Reno, and then took a bus from Reno down to Las Vegas where we spent what ended up being the last couple weeks of my dad’s life with him. Again, the doctors initially had given a pretty optimistic prognosis, I think, saying that he might have six more months or something like that, but what actually ended up happening is he passed away within a couple weeks. We were there during that process, obviously, and that was obviously, I think, for anybody who’s lost a parent, there’s a weird transition that happens for everyone when that happens. There’s nothing that shocks you or hits you in the same way, and that’s what we were going through alongside trying to support my dad through suffering, it’s like the loss of my parent.

And in the meantime, we’re in the middle of this giant hike, so after my dad passed away, we spent a few days with my mom and we talked to my mom about next steps, and once again, our initial plan was that we were gonna just stay there in Vegas, and talking with my mom, she was pretty insistent that we were not gonna do that and that we were gonna go back on trail. We made a plan together that she was gonna, she was gonna take us back to the start of the trail, and then she was gonna… She was somebody who had always kind of wanted to do this kind of thing in life, but had never really done it, so she made a plan that she was gonna train and get herself in shape and meet us at the end of the trail, she was gonna hike into the end of the PCT and meet us. It’s about… One of the funny things about the PCT is the actual terminus of the trail, the Northern Terminus of the trail is at the US-Canadian border, but that the exit, the nearest road is still 8 miles beyond there, so you have to hike another eight miles once you get to the PCT before you actually finish.

So my mom decided that she was gonna train and go on her first backpacking trip ever and meet us at the end of the trail, and basically that’s what she did. And we got back on trail and because we’d had the delay with going down to be with my dad, we really had to book it. So we… [chuckle] We took on early and got back our ultra running shoes on and spent two months hiking about 25 miles a day, minimum to make it to the end of the trail by the time the snow fell, and so it became this major like big epic quest, I guess that…

That it finished the way, I guess, we planned it, right? Like we made it by the end of September. My mom borrowed some backpacking gear from some friends, she enlisted my uncle to join her and she hiked in sort of her first overnight backpacking trip and met us at the Northern Terminus, and we sprinkled some of my dad’s ashes there, and then we came out of it.

So this was sort of obviously a big life experience, right? And I think like there’s a couple of different things I’d say about it. The first is that I’ve been thinking about thru-hiking a lot, and about like the way it sort of shapes you, and traditionally, I think when people went on long walks, like if you were to put all your belongings on your back and hike for five months, at the end of that, you’re gonna be in a very different place from where you started, right? That’s really migration. That’s not just a thing people did recreationally, that’s migration.

And I think there’s something… Probably there’s something hard-wired into humans that when you do something like that, you just come out of it expecting that you’re gonna be changed by it and that you’re gonna sort of be in a different world than the one where you started. And that’s something that I think it happens pretty naturally, and most people, I think who thru-hike will tell you that they were changed in some way or another by it.

But the fact that this happened in the context of my dad dying, and dying pretty young, I think that the way it changed me was to give me this sense that life is pretty short and it’s not guaranteed at all. I mean my dad had previously been entirely healthy, it’d probably been a decade since he’d been to the doctor before this, right? And so it just really came out of nowhere, and it just hit me and my wife as well, I think, in a way that just made us feel like we had to do the things we wanna do in life, and we have to think really hard about that, and pursue it because nothing’s ever guaranteed.

And that was really the experience, that sort of comprehensive experience is what led us, I think, to be more intentional about pursuing the things that we love to do, and ultimately that’s come down to travel and it’s come down to these sort of outdoor pursuits like hiking, and we’ve taken up some kayaking, and trail running, and we’re into mountain bike and sail at the moment, so just sort of pursuing those things as more central things in our life, I think that that was…

There’s almost a literal road to Damascus thing there, right? But it was pretty conscious at that point like I said previously, I hadn’t really thought in those terms, so it was just stuff we’re doing for fun, but after this, it was just sort of a very conscious, this is the lifestyle I’m gonna pursue.

Brett McKay: You also… It’s interesting with that story, thanks for sharing that, that you talk to other people who were dirtbaggers, and they had… A lot of them had similar stories of why they became dirtbaggers themselves. They had a big experience, someone died, they got a sickness they overcame, they lost a job, or whatever, and they decided that was the thing that I don’t know, shook them and said, “I gotta start doing the things that I really enjoy,” and they end up being a ski bum or a Thru-hiker, or whatever.

And it’s amazing, the different people from all walks of life, it was people who were once corporate CEOs or people who were just… They started doing that when they were in college and kept going.

Well, let’s talk about… Let’s get, so this is a sort of a big picture of why people become dirtbaggers, it might be a big life event that happens, or they’re trying to pursue… There’s a certain lifestyle they wanna live, a philosophy they’re trying to live out, but what I love about the book is how brass tacks you get with it, because I think a lot of people, they see those folks who are thru-hiking, they’re just camping all the time, they’re skiing all the time and they think, “Man, that would be awesome, but I can never do that.”

And the first reason people give for not being able to do that, basically to just make their whole life an adventure is money, specifically that they don’t have enough money to live a life of adventure. But in this book, you just say, you don’t actually need that much money, so how much money do you actually need to live a dirtbag lifestyle.

Tim Mathis: Yeah, you’re absolutely right. It’s a good question, and it’s a very common reason people look at these sorts of lives and say, “It must be nice to be able to do that,” or, “It must be nice to be able to afford that,” but one of the big driving points of the book, one of the big driving motivations is that you shouldn’t have to have a lot of money to have a good life, and to put together a good life.

And one of the big things that I think I’ve learned as we’ve pursued these types of things like traveling or thru-hiking or whatever, is that you can actually… You can do it on as small of a budget or as big of a budget as you want, right? The thing I’ve sort of talked about is really the goal of the lifestyle talked about in the book is about exploration. It’s figuring out how to sort of experience the world in its fullest and connect with the natural world around you in as direct a way as possible. And you can do that in a lot of different ways. So you can do that in the context of working a job and going out and being a weekend warrior, or you can do it in the context of drifting around Central America or whatever and surfing.

There’s a million different ways you can do it, so really, there’s a million different budgets you can do it on, it’s very individualizable. Maybe the most… Just to give a little bit of concreteness to this, there are actually are some pretty cheap ways that you can… You can travel and adventure. Thru-hiking for us was a nice wake-up call in that regard, because it really only costs about… Most people estimate it’s about $1000 a month to thru-hike on a pretty normal budget.

It’s not nothing, but it’s also actually not that much. You would spend… Most people in their day-to-day life are gonna spend well over $1000. What happens is if you choose to live a life where you sleep outside every night, and you eat out of grocery stores, and that’s really your only expense that actually narrows down your cost pretty significantly. So thru-hiking is a pretty accessible way to travel and adventure financially.

Another thing is a big part of our sort of adventure story has always been around traveling, and there are a lot of places in the world where if you can save up to get a ticket, you can survive on not much money at all once you get there. And we spent about four months traveling around Latin America after we hiked the PCT. And again, it was our budget down there was really only about $1000 a person a month.

So that looked like essentially bussing around, staying in Airbnbs or hostels, checking out beaches, going on hikes, doing low-key stuff but just doing it in cheap countries. So again, that $1000 a month is a good number for somebody who if you’re… I’m not… We’re budget travelers, but I’m not a crazy budget traveler. So I think that’s very doable. A lot of it really depends on where you’re going and what you’re doing.

I talk a lot about career and how you earn your money as well, and one of the things to think about is that going on adventures and these sort of big epic trips are not exclusive of work either. I think that that’s a sort of a misnomer, is that people just play outside all the time, and that’s typically not the case. People are typically working when they’re doing this, and you can… The world is populated by hostel working, like 22-year-olds with no money at all who are surviving basically just on room and board from the hostel and checking out Bolivia or whatever while they’re doing it.

Ski fields are populated by ski bums who make a couple of bucks an hour running lifts or whatever, but get the perk of being able to do what they love on the weekends or on their time off. There’s costs associated, but there’s also ways that you can figure out how to do it even if you don’t have… You’re not starting with much money at all…

Brett McKay: Well, I love in the section on finances, you lay out some rules, and I think that they not only apply to allowing you to live a dirtbag life, they’re just good financial rules, like for example, start with what you have rather than what things cost. Instead of thinking about, “I need to buy… I need to go to REI and buy all this cool stuff.” It’s like, “Well, what do I got already in my garage that I can use?”

Other great tips, go where you can afford, you were talking about that, it’s a no-brainer, things simplified, cut out the things you don’t care about. What I love about it is not only applicable to living a dirtbag lifestyle, but this is just good financial advice for just your life in general.

Tim Mathis: Honestly, most of our financial savvy came from my wife, and my wife was raised in a relatively… Both of us were raised very sort of working-class, but she was raised in relative poverty and she learned from her grandma, who was a bank teller her whole life and raised a family on that income, like how to get the most out of the money you’ve got and how not to waste it.

And so really honestly, most of the financial advice in the book was stuff that basically we’d picked up along the way from just the experience of having to do that. A million things you can take from people who’ve figured out how to get through life without much money that you can apply in a situation that’s focused on trying to adventure more, right?

Brett McKay: Well, I was coming back going back to this idea of career, so some dirtbags, they find careers that suit their adventure choice. So if you’re into skiing, you become a ski bum, you work the ski lifts, if you’re a surfer, you become maybe a surf instructor, and then you can surf or whatever, but besides that, what are some other ways that you saw that people were making money, having a career while still embracing this life of adventure?

Tim Mathis: Yeah, totally, ’cause you have to get through your life, you have to figure out how to make money and career is basically that… I think one of the things I think that’s important, it’s been important for me anyway, is to think about career and what you wanna do in life as separate entities, they overlap sometimes, but they’re not necessarily always the same thing. Sometimes your career, or your job is just the way you make money. And if you’re wanting to figure out how to make money while also spending a lot of time, taking a lot of time off, spending a lot of time exploring, you can think in a lot of different directions.

Like you said, you can do the obvious thing and become a guide and do that for a living, but sometimes you don’t want to… Sometimes that kills it anyway, so some people just aren’t… Not really people persons. So they don’t necessarily wanna do that. So you think about finding a career that is gonna be… It’s not gonna raise eyebrows if you take a lot of time off, or that’s contract-based and it’s sort of built-in that you’re gonna have time to yourself to do other things, and there’s a lot of different…

There’s a surprising number, I think, of jobs like that. When we’re living in the Seattle area, there were just a ton of tech workers who were kinda in that boat, right? They’d take Microsoft contracts, and they’d work on a project for a year and a half, and then they’d be done and they could do whatever they want before they took their next contract. I work… Like I said, I worked in nursing and healthcare is fantastic for that.

There’s so many jobs and so many different types of contracts you can take that it’s pretty normal to take a three-month contract and then take some time off afterwards, there’s a whole culture around it in nursing, and in lots of different healthcare fields. I’ve known people who are various types of healthcare techs who’ve done that sort of thing.

The first time I actually encountered this kind of approach to life was like when I was working construction for a summer after college, and I met a bunch of Union electricians who they would have… They would have jobs intermittently, so they’d be working on a job for eight months or whatever, and then over the winter they wouldn’t have any work, and so they would fly somewhere cheap, they would fly to Thailand or they would fly to Mexico or wherever, and they would just hang out there for a few months waiting for their next job because it was like one, it was an amazing life experience, and two, it was actually cheaper to do that than to stay at home.

There’s a lot of different jobs that are actually pretty well set up for this kind of thing. There are definitely some that are better than others, right? I mentioned that I did a Master’s degree and I was thinking about academics, and one of the whole reason that I quit that track is I realized it was gonna absorb my whole life, and I didn’t want my whole life to be devoted to my job. There are some jobs that it’s harder to do this with than others, if you’re young, you’ve got an advantage ’cause you can pick a career path that’s gonna be more amenable to doing the things you actually like and the lifestyle you want.

Brett McKay: Well yeah and so yeah, you’re thinking outside of the box here when it comes to your career. It’s like if you wanna be a trial lawyer, probably gonna be hard to do, be a dirtbag and that… Do that at the same time. But that’s okay, ’cause you find something you wanna do…

Tim Mathis: Yeah.

Brett McKay: Alright, okay, so I think another reason, and you talk about this in the book that people feel squeamish about becoming a full-time adventurer, is that it doesn’t feel responsible. It’s like you’re becoming a bum, just skiing is all you do. What’s your response to this reluctance.

Tim Mathis: Yeah, I think this is a big one. People think about responsibilities. That’s a really vague term. You’re like, “I’ve just got too many responsibilities.” What does that even mean? And there’s a couple of different things like I think it’s worth pointing out. One of them is that a lot of the things that people think of as responsibilities are actually just social expectations and they’re not actually things that you should or you have to do.

This gets right into that concept that dirtbagging, these people are basically part of a counter-culture because the counter-culture in a way, is critiquing a lot of traditional notions of what it means to be a responsible adult. Being a responsible adult doesn’t necessarily mean that you have to have… You have to own a house or you have to have nice clothes, or you have to pursue a certain type of career, or you have to provide all the best in terms of financial and material things for your kids.

Those things aren’t responsibilities in the sense that they aren’t things that you actually should or have to do, and I think actually some of those social norms that are thought of as when people think of the term responsibility are actually super destructive and not just for individuals, but they’re part of what’s driving the destruction of the natural environment that we live in, and overconsumption and this sort of disconnect from the people around us and the environment around us.

Some of those responsibilities are actually things that I think are healthy to kind of attack and critique. And one of the things I talk about, and one of the ways I think about this is that dirtbags are kind of like monks and nuns, in the sense that they’re the people who are practicing this approach to life in the most extreme ways, and they’re sort of learning things and communicating things that other people can learn from.

They might… Quitting your job and traveling for two years might be something that most people aren’t gonna do, but the people who do do it, they learn things about life that are gonna be really valuable to other people around them. So that’s one of the ways I think about how this sort of lifestyle can be responsible, is it’s actually communicating something important to the world and you’re learning important things about life that other people gain from.

Another thing I talk about though, is that the stuff that you actually should be responsible for, there are things… There are things you should do in life, treat other people with respect, you should meet your financial obligations, if you’ve got debts, you should pay them off, you should be a decent person, you should contribute to your community, all those sorts of things, but there’s no reason at all that you can’t do those things in the context of also pursuing your passions, if exploration is your passion, pursuing that is an entirely responsible thing to do that you can… That the world will gain from.

Brett McKay: Gotcha, so okay, I think that’s a good distinction. Make sure you make a distinction between your actual responsibilities and just social conventions. But I think yeah, the social conventions that can still be hard to overcome, right ’cause there are people who are just like, “Man, this is not what you’re supposed to do,” but who says? Right?

Tim Mathis: I think it should feel weird to live in a way that critiques the sort of mainstream approach to life, it should feel weird because those things are the things that are ingrained, and it’s a hard thing to do, ’cause it’s never clear, there’s always a lot of fuzziness, what are the shoulds in life? I think all of us are trying to figure that out as we go along.

Brett McKay: Alright, let’s talk about relationships and living the dirtbag lifestyle, so these early dirtbaggers, they’re probably bachelors, they had their buzz, but I imagine they weren’t married or had girlfriends, or whatever, is dirtbagging conducive to relationships?

Tim Mathis: Yeah, that’s another big one. And I think in the book, I definitely… There’s a little bit of a reality check with that one, where I’m like, “Yeah, actually, if you choose to go pursue some path in life that’s focused on, that’s gonna take you outside of normal social circles, it’s gonna take you… You’re gonna travel a lot, and those sorts of things, it is gonna impact your relationships, and there are some relationships that won’t survive that, and I think that that just is a reality.

It’s a thing that I’ve experienced myself as we’ve moved around. You do just lose some connections. The internet has made maintaining connections across a distance way easier, but you’re still not seeing the same people on a day-to-day basis. But I mean, the flip side of that is when you do this sort of stuff, you also meet other people who are doing the same. I think of it in a lot of ways, like any interest, if you become an engineer, you’re gonna meet lots of other engineers, if you become an adventurer, you’re gonna meet lots of other adventurers. So one of the things I talk about in the book is the concept that Cuba gets cool…

The general idea is, if you do cool stuff, and if you pursue stuff you’re passionate about, you’re gonna meet lots of other people who are doing the same, and you’re gonna build new relationships with them, and you guys are gonna inspire each other to do even cooler stuff, talk a little bit about marriages and relationships and that sort of thing, and those are tricky ones, like family relationships, I think are the trickiest because you don’t necessarily… You don’t always have the same interests as your family members. And I’ve been super lucky that Angel my wife and I both are really into this kind of thing, and so we’ve spurred each other along, it’s one of the reasons I think we’ve been able to build our life around it in a way that a lot of people wouldn’t. We both kinda wanna do it.

It’s true, there’re some people who their partner really doesn’t wanna… They don’t wanna spend all weekend every weekend running ultra marathons, or they don’t wanna take six months off and go bus around Europe or whatever, it’s just not their thing, and so those are trickier to manage, and then if you add kids into the equation, it’s a total crapshoot. At least with your partner, you know a little bit about them before you form a relationship. With kids, who knows what they’re gonna be like. It is true, and it impacts you and I think it’s one of those responsibility, things too. I think that if you have kids and it’s best for them to be in a situation at home or continue with their school or whatever. It is irresponsible to not provide that support for them, so there are ways in which relationships should and do impact on the choices you make… But that doesn’t necessarily mean that you don’t spend… Don’t focus your life on the things that you care about and think are important and figure out how to do those in different ways, it just means that your life looks different.

Brett McKay: Well, the thing about the kids, you actually encountered people who are living the dirtbag lifestyle with kids. I think there’s a lady. I think she might have been a single mom, had like six kids or something, and she was hiking a through trail with all our kids and she’s making it work, I was like, “Hey, good for her.”

Tim Mathis: Yeah, it’s our friend Amy, who we actually… We just kind of met her actually randomly in Seattle, we didn’t meet her through-hiking, but she hiked most of the Appalachian trail with two twins, and so two young sons and then two daughters, and one of her daughters has Down syndrome, so she’s figured it out, right? If she can figure that out, I think her sons were six or seven when they started the trail, one of them finished, one of them didn’t, but if she can figure out, a lot of people can figure it out. We have friends who right now are traveling around with two young sons, and they basically don’t have a home base, they just kind of travel to different parts of the world for a month or two at a time, and they run an online business, and they’re raising their kids on the road. Another woman who I actually grew up with in Ohio, I found out after I wrote the book, actually has been traveling in an RV with her…

I think she has three kids and her husband for years, just to different parts of the country. Home schooling, living on the road, so there’s people who figure it out, more power to them, and we haven’t had children, and it’s definitely made decisions less complicated, but people clearly do figure it out, and every family is gonna have different strategies that are good for them and work for them. But yeah, totally, people figure out how to live some pretty crazy lives, boat people are great for that too. Hang around the Marina and you’re gonna meet families full of people who are sailing around the world and doing all kinds of crazy stuff.

Brett McKay: Well, so okay, dirtbagging, can have adverse effects on your pre-dirtbag relationships like friends, family, before you’re just gonna lose touch with them ’cause you’re gonna be gone… Possibly be gone a lot. But as you said, you’re gonna be introduced to a new community, and that community of fellow dirt baggers, they can help you ease the financial burden, ’cause then you start sharing stuff with each other and they start sharing tips, or they… You crash at their place or whatever along when you’re visiting them, so that community that’s there can actually make this easier for you.

Tim Mathis: I think that that’s one of the things once you start meeting people who are into this kind of thing, it’s a very supportive community, it’s a web of people around the world really. After the trip to Latin America in 2016, we’ve spent most of our time with a general base in the Pacific Northwest in Seattle and then Tacoma, but we’ve been on the road for as much as we’ve not, and we tend to crash at people’s houses that we know… We either free camp or, we crash at people’s houses, and so the amount of money I’ve saved just from having cool supportive friends, it’s been in the tens of thousands of dollars just over the last few years, just because people are supportive and we try and do the same thing, if we can let people borrow our house or our car, if we’re not using it, we’re gonna do it because yeah, I think it’s part of the way that you support each other as people who are trying to live cool lives, like I said, when you start doing this, like some of the coolest people I’ve met have been through through-hiking, we met lots of other cool people through sailing events, we’ve sort of gone along for. You just meet people who live cool lives, and as you start to do that, you build a network of people all over the place that you can connect in and stay with.

Brett McKay: Well, let’s circle back. So one of the things that you talked about earlier, in your story becoming a dirtbag was one of those points was your master’s thesis on finding meaning in nature, and you have a section on this about how to build a meaningful life around the dirtbag lifestyle. And it sounds to me, it’s like, “Oh yeah, I’m gonna go and live my passion and whatever, be out in the outdoors doing things that I love,” but you highlight… There’s sort of a dark side, there can be a dark side to the dirtbag lifestyle, for example, I read this article too, you highlight the National Geographic talked about in ski towns, there’s been an uptick in suicides from there from just guys who would identify themselves as ski bums. What’s going on there? What do they think is going on there?

Tim Mathis: Personally. I kind of experienced this myself, so I mentioned that we hiked the PCT in 2015, then 2016, we took an extended trip to Latin America, and when we weren’t there, we were mostly traveling around the American West, and after a year, a year or so, I just really felt pretty empty and just this sense that we were… I was like Spending life drifting around looking at pretty things, which is great for a week or two even a month, but after a while you start to feel like, what in the world am I even doing with my life? Like, why am I doing this? And I think that’s one of the big traps with pursuing something that’s like a passion or recreational, or even something that across time you’re gonna lose your ability to do, it’s one of the things with being in those types of sports, as you get older, you just physically lose the capacity to do it, either you get injured or you just… The natural process of aging. And if you’ve been centering your life on that stuff, that can trigger some pretty intense mid-life crises, you’ve hit at a point where this thing that you really have centered your life around, you can’t do anymore.

It’s true that… The National Geographic article said there was data saying that there’s suicide rates are higher in ski towns, kind of conjecture on my part, but I would imagine that that’s basically the dynamic. You have these old ski bums this has been their life and now they can’t do it, so they don’t figure out how to make the transition. And one of the reasons I wanted to talk about that in the book is ’cause I actually think it is an essential… The book itself is really focused on how do you manage to live a good life and do the things that you really need to do to survive in this context sort of dirtbagging context. And I do think that actually having sense of meaning and purpose in life is an essential because eventually you’ll either give up on the lifestyle or you’ll just give up on life in general, and neither one of those really is…

Neither of those is a good outcome. There’s a really good book that I used as a framework for my chapter by a writer named Emily Esfahani Smith, that’s called The Power of Meaning, and it’s basically about this concept, it’s about the question of how do human beings develop a sense of meaning and purpose in life and the thing I like about it is a lot of times when you think about meaning and purpose it’s always very ethereal, it’s spiritual. And it doesn’t mean anything. The book is basically based on a series of interviews she did with people who reported having a strong sense of meaning in life, and she looks at the things that they did and have that helped to produce that, and so she gives some really practical guidelines and directions and I think like the things that she comes to are really useful to think about, and they’re true for anybody.

So they’re true for people, if they’re sort of working their nine-to-five, and they’re just as true for someone who decides to set out on the ocean and spend their life sailing between Pacific Islands. So the thing she talks about for the ways that people maintain a sense of meaning are, one, they have a sense of community connection, so they have a sense of belonging and a place in the world, building a community of people, even if you’re sort of drifting around building a community of people that you feel connected to and having a clear sense of how you fit into it, then there’s also a need to feel like you have a purpose and in a very specific kind of way, right.

You feel like you’re useful to the world, I think that’s a thing that I come to a lot, is if you’re feeling like you just not sure what your direction is in life, you just figure out ways to make yourself useful. It’s having that sense that you have a purpose in the world, that’s very concrete, like you’re doing something beneficial for the world. She talks about a sense of transcendence, which is the sense of having a connection beyond yourself, again, transcendence that’s a very… Like very, fiery kind of word, but really what she’s talking about is feeling a connection to the world around you, whether that’s your community, whether that’s the natural world, whether that’s some sort of religious connection, people who feel like their life is purposeful, have a sense of connection to transcendence, and personally, I think this one is very natural to a lot of people who are in the community, like the sort of outdoors community, a lot of people go out into the wilderness and into mountains or into the woods on a regular basis because they have this sense of big-ness and transcendence, and they’re part of something that’s much bigger than themselves, so that’s one that I think outdoor recreation is…

It’s so popular because it gives people that sense of transcendence in a way that a lot of other things don’t. Then finally, she talks about storytelling, basically, she’s just saying you have to be able to think through your story, your own personal story, and place it in the context of the world, you have to be able to make sense of how your life fits into the bigger picture, and that’s really what telling your own story is about. It’s being able to make sense from a story perspective of how you fit into the world. So all those things, I guess, are things that… That’s not very specific, but I think it’s good because throughout life, you’re gonna have to think of how to cultivate a sense of meaning, and the way to do it is to think about the different things that will actually provide that sense of meaning, and those things you can work out in a lot of different ways, in a lot of different contexts.

Brett McKay: So what did you do personally when you were filling that sort of existential funk after the tour, the American West, what did you do to inject some more meaning into your life?

Tim Mathis: Yeah, good question. So one of them I went… Basically, I went back to my job as a mental health nurse, so that is definitely one of the things where I feel like I’m providing some value to my community. I worked for about 10 years as a mental health nurse, so I went back to that and I started working more shifts there, and then my wife… One of the things I haven’t talked about is, my wife started a business called Boldly Went that was focused on holding events in the outdoor community where people could tell their stories, and then we created a podcast and sort of online content coming out of those stories. So building that business was another way that we definitely started to re-cultivate a sense of meaning and purpose and direction.

Brett McKay: Have you… I imagine you encountered a lot of people out on the trail who were… They were basically just trying to escape from something, escape from life, and they weren’t really trying to embrace something constructive or meaningful. How do you make sure that if you decide, I’m gonna become a Pacific, I’m gonna become a true through-hiker, that you’re not just running away from your problems and you’re actually trying to turn towards something constructive?

Tim Mathis: That’s a good question. I think that human beings are pretty good about instinctually recognizing when something’s wrong in their situation and something needs to be done, but they’re not always that good at figuring out what to do in response, and I think you’re right that there are a lot of through-hikers out there who life has just been a mess. And so they go on the trail to try and solve it, and I think that’s true with a lot of escapists kind of things. If you travel internationally too, and you get on the backpack or circuit, you’re gonna meet those kind of people as well who are just basically like, home sucked, stuff went really sideways. So now I’m in Ecuador and I don’t know what I’m gonna do when I go back. It’s kind of tricky, and I think part of the process itself helps a lot of people figure out what to do next, the general process of travel, the general process of doing something physical a lot of times, a lot of people sort out their problems on the run, a lot of people sort out their problems while they’re traveling, so I think…

I think it’s a good prescription when there is something wrong for a lot of people just to do it and see where it goes, but… Yeah, but I think that, again, it comes back to that question of responsibility. If you’re running away from doing things that you should do or doing things that you need to do, then you’re going down the wrong path, you have to figure out how to address those things how to confront those things whether that’s like problems in relationships, or if it’s financial problems or whatever. You have to figure out how to address those things. A lot of times, what that comes down to is finding something meaningful to replace those relationships or drug addictions or whatever with, just finding something better to replace it with. Move in a healthier direction. It’s a good question. It’s not an easy question, but yeah, I think these types of processes can be part of the answer.

Brett McKay: Well Tim, where can people go to learn more about the book and your work.

Tim Mathis: Yeah, so the easiest place to find the book is on Amazon, it’s true of pretty much everything in the world, so… Yeah, Dirtbag’s Guide to Life: Eternal Truth for Hiker Trash, Ski Bums, and Vagabonds, it’s on Amazon, it’ll be on a bunch of other sites as well, pretty much wherever you buy your books, and then I’ve recently launched a blog called dirtbagsguide.com that’s focused on continuing to write on some of the same things that were in the book, but just trying to make sense a little bit of the 2020 context as well. And I have an Instagram account that’s just… If you just search dirtbag’s guide to life, that’ll pop up, but I’m not that great at keeping that up, and I’m kind of over social media marketing, but you can go to Instagram too, and then my wife and I’s business is called Boldly Went Adventures it’s, boldlywentadventures.com. There’s about four years of podcasts there that are stories from all types of people in the Outdoor community, a lot of blog content, that sort of thing that people can check out as well.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Tim Mathis thanks for this time. It’s been a pleasure.

Tim Mathis: Yeah, man, thanks for having me. It’s great.

Brett McKay: My guest here’s Tim Mathis, he’s the author of the book, The Dirtbag’s Guide to Life. It’s available on Amazon.com. You can find out more information about his work at his website, boldlywentadventures.com, also check out our show notes at aom.ios/dirtbag where you can find links to resources. We delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The AOM podcast, check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you’ll find our podcast archives, and if you’d like to enjoy ad free episodes, the AOM podcast, you can do so on Stitcher premium. Head over to Stitcher premium dot com, sign up, use code MANLINESS at checkout for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS, and you can start enjoying ad free episodes of the AOM podcast, and if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple podcast or Stitcher, it helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you, please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think will get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support until next time this is Brett McKay reminding you not only to listen to AOM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.