Editor’s Note: This is a guest post from Wyatt Knox from Team O’Neil Rally School.

With winter comes a whole new range of driving hazards — darkness sets in much earlier, wind and snow reduce visibility, and ice makes roads slippery and treacherous. Annually, there are over 100,000 injuries that occur from car accidents on snowy or icy pavement. If you live in an area where snow is a winter reality (roughly 70% of the U.S. population lives in areas that average at least 5 inches of annual snow), then it’s vital to have the skills necessary for driving safely in inclement conditions. One of those skills is how to recover from a skid. The feeling of losing control of one’s vehicle can be quite scary, and it’s easy to panic and make the wrong moves if you don’t know what to do.

Below we outline the 5 most common types of skids on wintery pavement, and how to recover when they happen. In general, if you stay calm, restrain yourself from making drastic movements, and follow the tips below, you’ll be able to safely travel the nation’s highways and byways throughout the winter months.

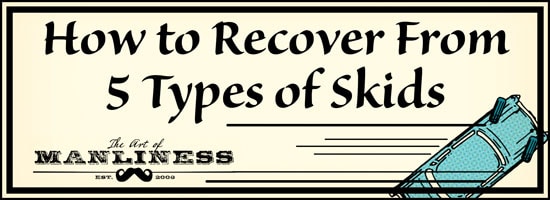

1. Wheelspin

Wheelspin occurs when you try to accelerate too abruptly or enthusiastically for the available traction. The tires will start to spin at a faster rate than the vehicle is actually traveling, which can lead to different outcomes depending on whether the vehicle is front, all, or rear-wheel drive. The cure for wheelspin is simple: just back off the throttle until the tires regain traction, and try ramping it up more slowly and cautiously next time. This makes wheelspin a very easy litmus test for how much grip you actually have. For example, intentionally hitting the gas while leaving your driveway on a snowy day to see how easily the tires spin is like dipping your toes into a pool to test the temperature.

Wheelspin is generally to be avoided in turns, but can often actually work to your advantage when moving in a straight line. On pavement or glare ice, there is no real benefit to spinning the tires, but we need to think of the road surface as three dimensional in many cases. Say you have a few inches of snow on top of a good paved or gravel surface; spinning the tires will chew through the fluff and catch good traction on the underlying surface, which can often make the difference between getting up a snowy hill or sliding back down. The same is true in mud or anywhere else there is a slippery material on top of a hard, grippy material.

Traction control in some vehicles will not allow your tires to spin in this fashion. It will either cut the throttle, apply brakes to the spinning wheels, or both. This might mean that your vehicle can’t make it up slippery hills or even get out of your parking space if there’s snow. Try the same thing with the traction control off and you might find that you have no problem at all.

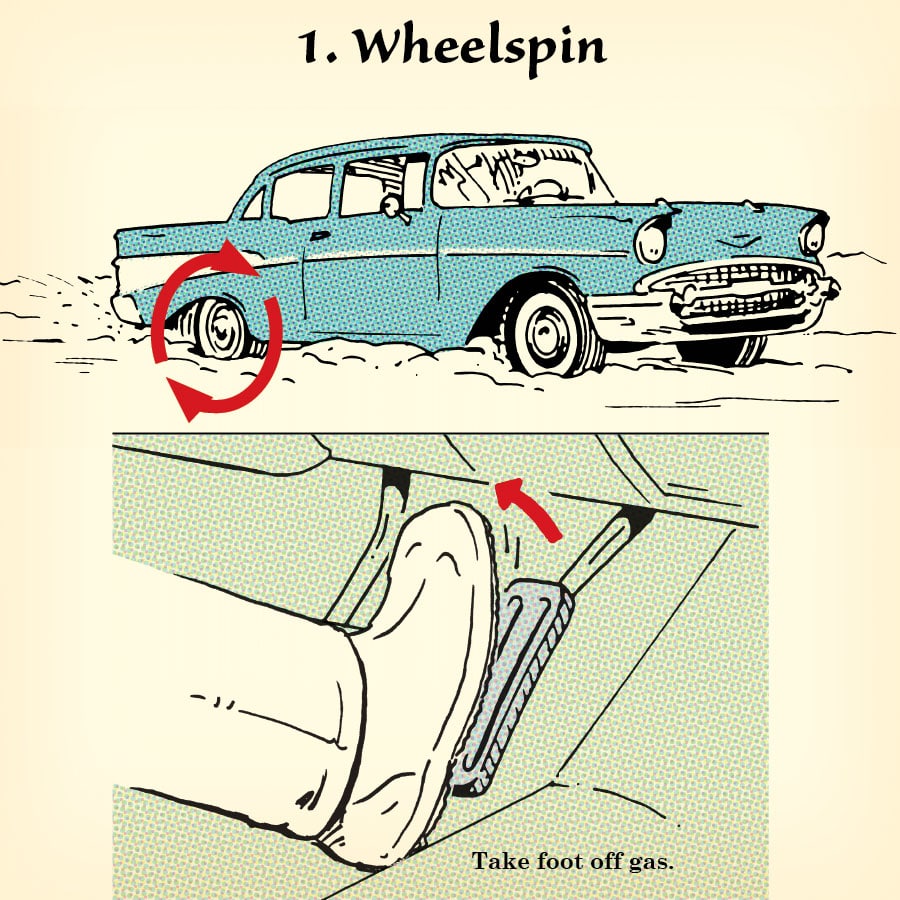

2. Wheel Lockup

Wheel lockup occurs when you try to brake too aggressively or suddenly for the surface you’re on. The tires will essentially stop turning while the vehicle is still moving. The solution is thankfully very simple: release the brakes until the tires start to turn again. You may need to release the brakes completely, and try braking again more softly and progressively.

You may find that you can actually brake fairly hard on a slippery road, as long as you do it smoothly. If you suddenly go from 0% to 50% brake on the snow, for example, the tires will probably lock up. If you build up the brake pressure slowly and progressively, however, you might be able to brake well beyond 50% on the same surface. Just like with wheelspin, wheel lockup can be a very handy gauge to have in changing conditions. Occasionally test the brakes in a straight line as you’re driving on a slippery road to feel for wheel lockup; this is a good indication of how much grip you’re working with.

Wheel lockup can also be an advantage in a straight line, in the same conditions that spinning the tires would have benefit. On a loose surface, locking the tires will scuff away the top surface, often digging in and plowing the soft stuff out of the way to find better grip. On snow, gravel, and especially sand, locking the tires up can stop the vehicle very quickly.

Anti-Lock Brake Systems (ABS) will not allow your wheels to lock up; they’ll pulsate brake pressure at all four wheels so that the tires keep turning. This means that on a loose surface, your car may not decelerate very well, and you’ll need to leave extra braking and following distances to compensate.

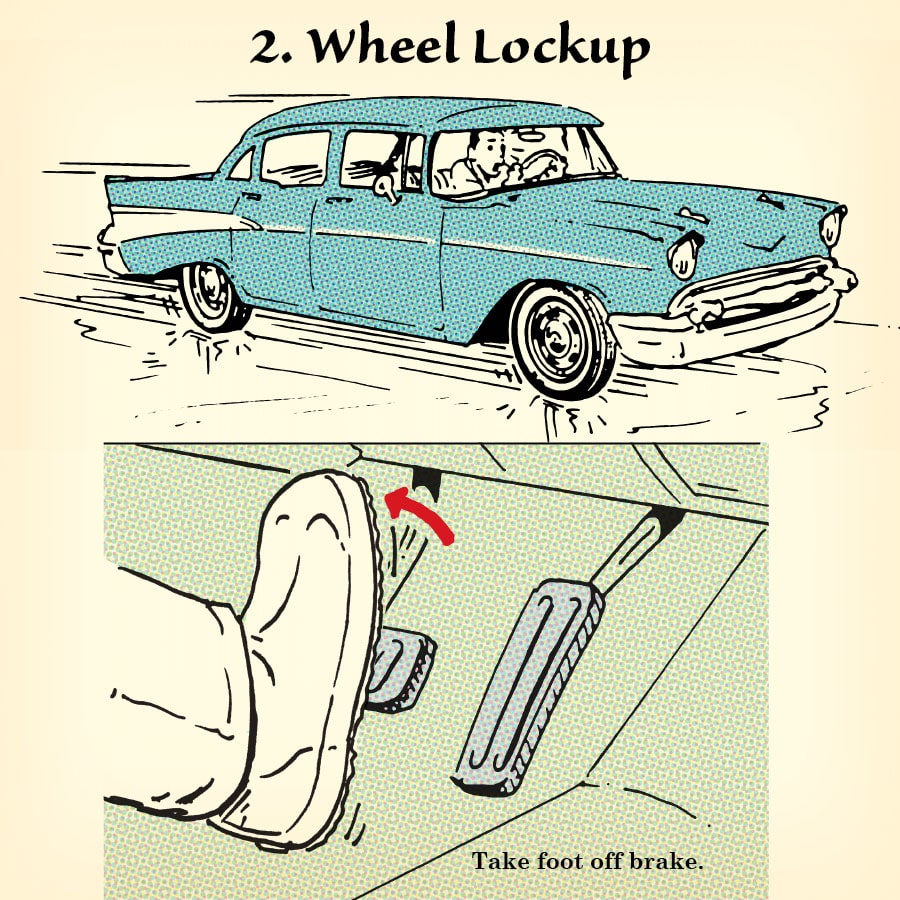

3. Understeer

An understeer skid occurs when the front tires lose grip, and the car is unable to turn around a corner. It’s often referred to as “plowing†or “pushing,†and it most often occurs when you enter a corner with too much speed for the conditions. If you’re doing 70 mph in a 30 mph corner, unfortunately it’s all over…look for something soft to hit and work on reading the road and the conditions better next time. If you’re only slightly too hot coming into a corner, the solution is to let off of the gas and apply the brakes gently, while looking where you want the car to go at all times.

Spinning the front tires can also cause massive understeer. In a front-wheel drive car, don’t spin the tires if you want to have any chance of turning. Locking the front tires in a corner will also cause horrible understeer; if you’re braking aggressively in any vehicle and trying to turn at the same time, you’ll need to release the brakes somewhat in order for the car to steer.

Understeer also happens because of weight transfer. If you’re accelerating, especially up a hill or in a vehicle with soft suspension, there won’t be much weight on the front end and you’ll have to lift off the gas or apply the brake a little to get the nose down. Weight on the front tires will push them down onto (or into) the surface, often giving you much better grip.

Resist the temptation to give the car more actual steering when you enter an understeer skid. It’s the natural thing to do — “The car won’t turn, so I’ll turn more!†— but the problem needs to be fixed with the pedals and not with your hands. You’re either accelerating or braking too much or not enough; adding more steering will only compound the problem and waste valuable time. You have the most grip with slight steering inputs — if your front tires are turned at high angles there’s very little chance they’ll do what you want.

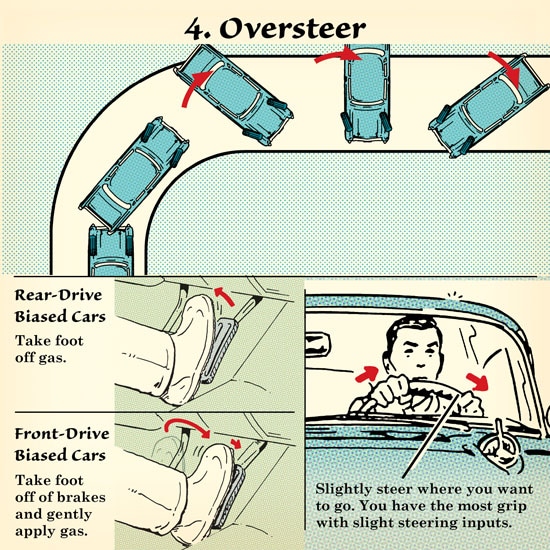

4. Oversteer

An oversteer skid occurs when the rear tires lose grip, and the rear of the vehicle starts to slide sideways. This most often occurs because of wheelspin in rear-wheel drive (and some all-wheel drive) vehicles, and the solution in that case is simply to back off the throttle, look where you want to go, and slightly steer in that direction.

Oversteer also occurs fairly often when you’re going too fast for the conditions, and apply brakes while turning a corner. This will shift much of the vehicle’s weight onto the front tires and off of the rear. The rear will start to come around simply because there is no weight on those tires, especially in pick-up trucks, front-wheel drive cars, or other vehicles that are naturally light in the back. This also happens going downhill around corners for the same reason. Again, the solution is to look down the road where you want to go, release the brakes, and even accelerate a little to put some weight back onto the rear tires to stop them from sliding.

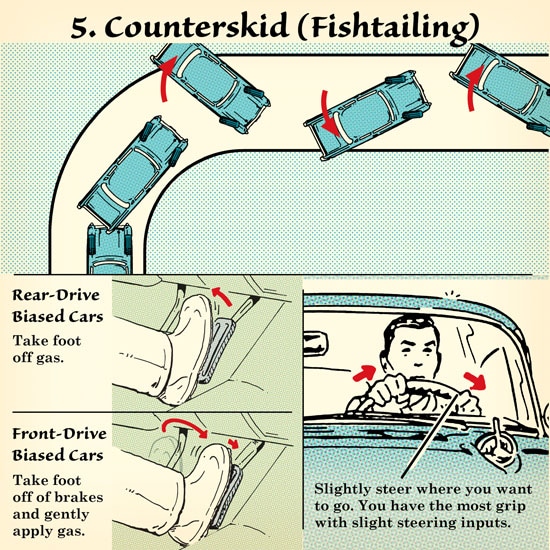

5. Counterskid

The counterskid occurs when you have met with oversteer and failed to correct appropriately. The rear end of the vehicle will skid back and forth, often building momentum with each swing. If you don’t fix the first or second skid, you’ll often generate enough energy to make the third skid very violent and difficult to recover from.

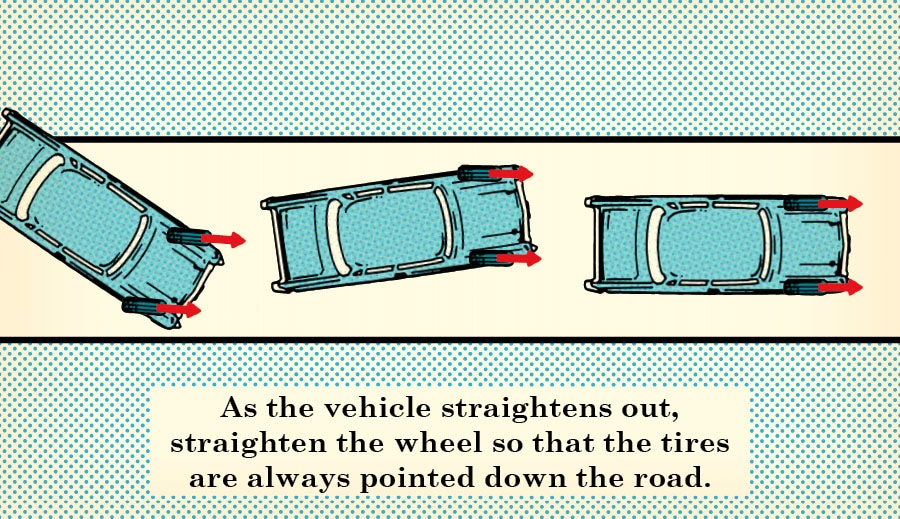

When you encounter oversteer, the key is to look down the road and only use enough corrective steering to point the front tires where you want to go. As the vehicle straightens out, straighten the wheel so that the tires are always pointed down the road. Counterskids most often happen when drivers correct late, overcorrect, and then repeat this mistake until they’re off the road. Known as “fishtailing†or “tankslapping,” counterskids can be difficult to recover from, but your vision is the key. Regain control of the steering, don’t let the car bounce back and forth, and you’ll be fine.

___________________

Wyatt Knox is a former US Rally Champion in the Two Wheel Drive Class. He is also the Director of Special Projects at Team O’Neil Rally School, instructs at several performance driving schools in the US, and currently races in both North and South America.

Illustrations by Ted Slampyak

Tags: Cars