Editor’s note: This is a guest post from Joshua Klein.

Earlier this week, I explained why every man should know how to repair his own furniture, and offered some tips for mitigating the need for such mending. In this concluding installment, I’ll go into the how of furniture repair: the basic tools to have, the joints to know, and the instructions to get things fixed up right.

The Basic Toolkit

Fortunately, you don’t need tons of expensive or exotic tools to repair your furniture. In my studio, I have a wide variety of tools perfect for specific tasks, but to get started you don’t need much. Here’s a list of the basics:

1. Hide Glue

This is the single most important tool you’ll need. Adhesive choice can make or break the long-term success of a repair, so don’t try to one-up the artisans of the past. Ancient Egyptian tombs were discovered with furniture still standing thanks to the strength of hide glue. The reason historic furniture survives use for hundreds years is because it was glued with this adhesive.

Hide glue is exactly what it sounds like: an adhesive made from the skins of animals. Furniture grade hide glue comes from cattle hides. The hides are heated in a water bath to extract the gelatinous glue. Once drained off and dried, the glue is ground into granules for sale. Some manufacturers then add ingredients to it to alter the working properties to make it easy to use for repairing wooden objects.

The real beauty of hide glue is that it will dissolve again when hot water is applied directly to it. This makes repairability not only easy but successful. Modern synthetic glues seal the surface of the wood, guaranteeing that no glue will ever be able to be used on top of it again. Every glue fails eventually. Believe me. I see failed joints all the time full of Gorilla Glue and these repairs take the most time to do. Put simply, once a fancy-pants modern synthetic glue is used, no future glue will ever make the joint as strong again. And when you do try to repair it in the future, good luck trying to safely disassemble it.

Another benefit of hide glue is its strength. It’s the epitome of the Goldilocks principle: not too weak, not too strong, but juuuust right. Don’t buy the marketing about the strongest glue on the planet. You don’t want that. The glue line in a joint is supposed to be the sacrificial element in the system. Think about it: when the chair falls backwards on the floor, what do you want to fail, the glue line or the wooden components? Adding more glue into a joint is way easier than trying to repair a severed tenon.

The easiest and most readily available form is Franklin’s Liquid Hide Glue. This little brown bottle can be found at many hardware stores. Another alternative is Patrick Edward’s Old Brown Glue. Watch the shelf life and you’ll be all set.

2. Glue Brush

Because hide glue is water-based, I use any old waterbase brush from the craft store for spreading the glue. For gluing joints and veneer, a 3/8†wide brush will do just fine.

3. Clamps

Don’t skimp here. You don’t want your father’s rusty, greasy pipe clamps from out in his garage. Besides being too heavy for delicate items, you want clean clamps dedicated to fine work like this. I use Irwin’s Quick Grips almost exclusively because they give the right amount of clamping pressure, are lightweight, and have built-in clamping pads so you won’t mar your furniture when tightening. Get yourself 4-6 36†clamps. The 12†kind are handy to have around too.

4. 24oz Dead Blow Mallet

There’s nothing sexy about this mallet but boy is it handy. They’ve got sand or lead shot in the head that helps give an appropriately directed thump where needed.

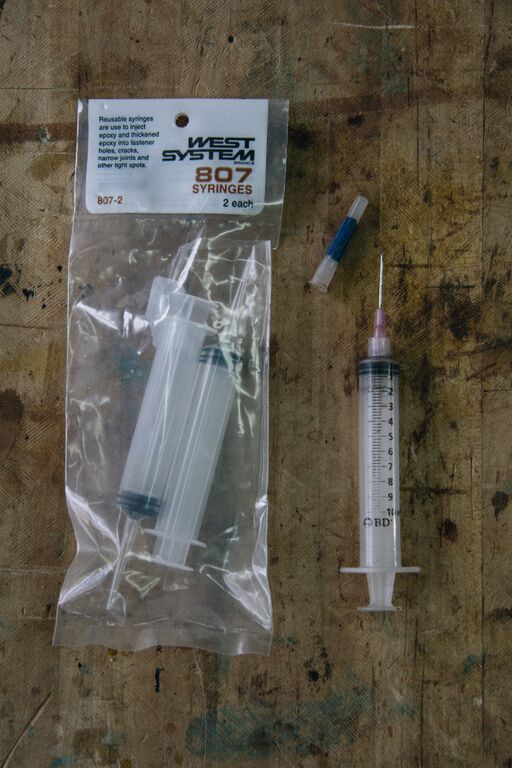

5. Medical Syringe or West System Epoxy Syringe

In order to get hot water into a joint, you will need a way to apply small amounts directly to the joint line to let it seep in. Small syringes are perfect for this. I heat water in the microwave, fill the syringe, and squirt it exactly where needed.

6. Fine Rasp or 80-Grit Sandpaper

You’ll want a way to clean up glue residue on tenons and inside mortises before re-gluing. You don’t want to remove any wood from the joints, just hardened clumps of old glue that may impede reassembly. If it’s hide glue applied on hide glue, this clean-up is not for adhesion purposes, just ease of assembly.

7. High Pressure Injector

While not absolutely necessary, it can save you a lot of effort and time in the right circumstance. By drilling a 1/16†hole into the joint from the underside, you can inject water-diluted hide glue into a loose joint. By plunging the tenon in and out a few times until you see glue squeezing out around the mortise, you introduce fresh glue into the joint without complete disassembly. It’s an extra $30 well spent if you save yourself a few hours wrestling a big project.

Before we move on, here’s another no-no to add to Gorilla Glue and giant clamps on small delicate parts: nails. Don’t use nails to “tighten†a loose joint — they don’t stabilize it. It only makes disassembly a mess. Removing nails always mars the surface and if you don’t see them before forcing a joint apart, you end up with major damage.

Know Your Joints

Last time I offered an illustrated overview of the major parts of chairs. Such terms are good to know in order to save you from having to struggle over what to call the “spindle-thingy†that’s broken.

How are these things put together, though? Only when you’ve got that under your belt can you come up with a good way to repair it. So let’s take a look at some of the most common furniture joinery.

The Mortise and Tenon Joint

This joint is the most fundamental joint you will find in antique furniture. It consists of a hole (mortise) and a correspondingly shaped tenon which fits snugly into the hole. The joint can be rectangular or circular. This joint is used on just about every part of a chair, the bases of tables, and chests with drawers.

The Dovetail Joint

The dovetail is the strongest way to join two boards at 90 degrees to each other. It consists of a wedge-like shape (like half a bow tie, or eponymously a dove’s tail) cut into a board, which is then joined with a piece that’s been cut to fit. The genius of this joint is the mechanical lock that secures the boards to each other even before you glue it. These are the joints that people ogle at when they pull open an antique drawer. I admit they look attractive but I assure you, they’re more than a pretty face. It’s a very strong joint and that’s why it’s used.

The Dowel Joint

The Industrial Revolution sought to mechanize construction in order to manufacture furniture less expensively. One of the solutions to economize construction was to replace the traditional mortise and tenon joint with two or three dowels. This joint is not as strong as a full tenon and can make repair slightly more challenging.

There are many more joints for special situations but for the home handyman these three are going to be the bulk of what you find in your task at hand.

The Ten Commandments of DIY Furniture Repair

As an overview to the basic principles of restoration, I’ve put together a list of The Ten Commandments of Furniture Repair. Because it’s intended to serve as a reminder when it comes time to get out the glue, print it out and hang it up in your workshop. It’ll come in handy.

- Thou shalt honor original artisanal workmanship.

- Thou shalt preserve original material.

- Thou shalt not use nails.

- Thou shalt disassemble carefully.

- Thou shalt use hide glue.

- Thou shalt use appropriate clamps.

- Thou shalt dry clamp first.

- Thou shalt not remove a historic finish.

- Thou shalt not use polyurethane.

- Thou shalt take it to a professional when necessary.

How to Make 4 Common Furniture Repairs

Alright, so you’ve got your hide glue. You’ve got clamps. Dead blow mallet? Check. We’re ready to get into the nitty gritty. Here’s how to make four common furniture repairs.

1. Loose Chairs

This is by far the most common repair you will run into. We ask much more of our chairs than any other piece of furniture. Because of long hours of use and strain, these things take a beating.

We all know the experience of plopping down into a chair that groans and creaks with each movement you make. Maybe you are even in the place of perpetually shoving the stretchers back in after they pop out of the legs each time a person sits down. Let’s take care of that before someone gets hurt.

If the chair only has one loose joint and the tenon comes all the way out of the mortise, that’s as easy as applying new hide glue and clamping it back in place. What if it doesn’t come all the way out? In that case, a high pressure syringe can be a life saver. Drill a 1/16†hole under the joint at an angle so that it goes into the mortise. Then dilute your hide glue a little bit in warm water, fill the syringe, and plunge the glue into the hole. In order to move the glue around the tenon, pull the tenon in and out as much as is possible until you see glue seeping out of the mortise all the way around the tenon. Clamp it up overnight and you’re done.

What if many joints are loose? In this case it is best (and more efficient) to disassemble and reglue. Before you start disassembly, make sure you examine all the joints to make sure no one drove a nail into the joints. If they did, you can either use a nailset to drive it all the way out the other side or dig around the head in order to get a grip on it for pulling it out.

Start by labeling each joint with blue painter’s tape. Put the same letter or number on both the mortise and the tenon side of the joint. Once every single joint is labeled, you can carefully begin to spread the joints apart. The Quick Grip clamps I recommended can be reversed to become spreaders. You can use the spreaders to apply a slow and even pressure. Make sure the spreading is balanced on both sides and not just one joint at a time.

If the joints are not loosening up with spreading pressure, try using your dead blow mallet to give it a gentle rap. This controlled jolt can cause the glue line to fracture, successfully releasing the tenon. If this doesn’t work, use your medical syringe to inject a tiny amount of warm water at the joint line. Allow the water to seep down into the mortise, wiping away any water on the finish. After you allow it to sit a few minutes, the glue will begin to soften, making it easier to spread free. Any joint that isn’t loose at all even after a few taps of the mallet should be left alone. Don’t fix what ain’t broke.

Once all the components are disassembled, knock any clumps of hardened glue off the tenons with a fine rasp or 80-grit sandpaper. The goal is to remove glue without removing wood. Do not remove wood from the tenons. That would make your joint loose even after it’s glued!

When every joint is cleaned up, it’s important to do a test run assembly. This “dry clamp†is critical not only to understanding the logical flow of assembly but also because it shows you if there will be any problems refitting the tenons back in. Sometimes chunks of glue can hold you up. Put all the parts back together and apply full clamping pressure just as if it was the real thing. Once you’re satisfied that you know how it’s going to go, disassemble and get your glue.

This liquid hide glue should give you 20-30 minutes of working time before it starts to gel. Apply glue to the tenon and the mortise, spreading it around for an even coverage. Assemble the entire chair and clamp it with firm pressure on a flat surface. Be careful not to overdo the clamping pressure here. It is possible to deform the frame out of square this way.

You should see a tiny amount of glue squeezing out of the joints. That’s how you know you used just the right amount. You can clean up that glue while it’s still wet with a rag that’s damp with warm water. Leave it clamped up overnight and you’re all set. Your chair has new life!

2. Loose Veneer

Although veneer is attractive and an economical use of resources, it can be susceptible to damage. Eventually every glue fails and in this case when it does, you’ve got little chips of veneer that pop off. When this happens, make sure to save every piece. Lay the fragments in place to double check you’ve got it all. If it fits in with no gaps, that’s a good day. If there are gaps, you can use an exacto knife to cut new veneer pieces to fit the losses.

After you’re sure you’ve got all the pieces, test to see if the glue is hide glue. If it’s an antique, I bet it will be. If it’s modern, who knows. The best way to test is to place a little bit of warm water or saliva (I’m serious) on the glue under the veneer. Let it sit for 20 or so seconds. If it becomes sticky, rejoice, because you’ve got hide glue. If not, you have to get an exacto knife and carefully scrape the glue off the surface without removing wood. (A black light bulb can help tremendously to show you where to scrape.)

Once you’re sure the veneer and where it broke out of is free of synthetic glue, spread your liquid hide glue on the back of the veneer fragment and on the furniture. To clamp it, sometimes I use a small piece of Plexiglas to flatten it in place with clamping pressure. If it fits nicely, I use a blue tape butterfly technique. I simply twist a 1-2†piece of painter’s tape in the middle and stick one side to the veneer and pull it to where I want it and stick the other side down. It works really well on the edges of tops to pull the veneer tight. The twist in the tape makes it a lot stronger and enables you to see what’s going on underneath. After leaving it overnight, remove the tape and wipe up any excess glue with warm water.

3. Stripped Screws

Although minor, this is a really common issue. The way that people usually deal with this is to remove the hinge and drill it out to insert a plug of new wood. They then drill a new hole. This works but is most often unnecessary. A much simpler fix is to fill in the hole a little bit. Some people use toothpicks to fill up the hole, but I use cloth. Take a small piece of cloth, dip it in glue, and use an awl to jab it into the hole. Try to push the cloth to one side of the hole rather than clumped into the middle. After the glue fully dries, you can trim it flush with a razor blade and reinstall the screw. More often than not I need to use a drill bit to clear a straight path for the screw to enter. The repair is easy, strong, and won’t be a headache to deal with later.

4. Stuck Drawers

You know that chest of drawers that no one wants to use because the drawers are always stuck? Let’s take a look at what may be going on. When drawers are hard to pull in and out, the first thing I look for is to see how much wear there is on the drawer sides and the runners on which it slides. On a piece that has seen more than a century of use, these parts wear down significantly. Once the drawer sides are worn to nothing at the back, then the drawer bottom starts dragging. Also, the runners frequently have a deep groove worn into them.

Let me offer you a few fixes. First, try prying the runners off and flipping them over. This will give you some new usable life without having to make new pieces. Often they were just glued and nailed on. Apply new glue and carefully line them back into place. The nails will hold them in place as the glue dries.

The worn drawer side bottoms can be planed straight and new wood can be glued on and shaped to replace what’s missing. This is something I would recommend to someone with some woodworking skills. If that’s not you, this may be a task for a professional.

Other drawer issues can be seasonally related. When the humidity rises in the spring, wood absorbs more water from the environment, causing it to swell. This makes moving wooden parts harder to operate.

If you notice the drawer is really tight, find where it is rubbing and carefully plane it down. Sides? Top edge? Is the drawer bottom dragging? I try to plane the interior elements inside the case before the actual drawer itself because then it won’t be seen. Plane a little, check the fit. Plane a little more, and again check the fit. Take your time with this job. Each fitting should give you feedback about the adjustments you’re making.

I will add lastly that sometimes just waxing the drawers’ sides and runners with paste wax will do the trick. You can certainly do this to buy yourself some time but it will not fix the underlying issue. It may only temporarily address the presenting complaint.

Conclusion

There are many other repairs one could encounter in their home, but I think these examples will show you the general approach you can take to repairing your furniture. A couple key principles will set you on the right path: 1) use hide glue, and 2) minimize invasive repairs. This is a recipe for success. Any time you are thinking about removing original material or replacing parts, make sure you know that it is absolutely necessary. It’s always easier for a professional to work on a hide glue repair on original material than new parts stuck together with Gorilla Glue.

_______________

Joshua Klein is a furniture conservator/maker in Midcoast Maine. He is currently writing a book about the furniture making of Jonathan Fisher (1768-1847) of Blue Hill, Maine. He regularly blogs at The Workbench Diary (http://workbenchdiary.com) and is the founder of Mortise & Tenon Magazine (http://mortiseandtenonmag.com).