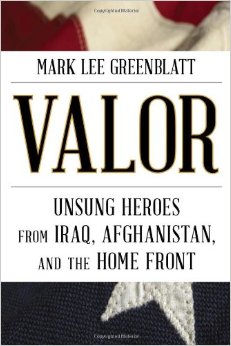

In today’s episode I talk to author Mark Greenblatt about his book Valor: Unsung Heroes From Iraq, Afghanistan, and The Homefront. In his book Mark highlights nine servicemen who displayed bravery above and beyond the call of duty. His stated goal with this book is to introduce Americans to the “Audie Murphy’s” of this generation.

Show Highlights:

- Why the American public knows so little of our modern day war heroes

- Riveting stories of heroic action in combat

- Why one war vet still sends money anonymously to a family in a remote village in Afghanistan

- What we can learn from the men in Mark’s book

- And much more!

You can visit Mark’s website and write an email directly to the men (or the families of the men) highlighted in the book. Mark says they’d love to hear from you.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Finally, I’d really appreciate it if you’d take the time to give our podcast a review on iTunes or Stitcher. It’d really help us out. Thanks!

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. So in American history and culture we have our famous war heroes from the Civil War, from the Revolutionary War, World War I and World War II. These were men who were celebrated for their acts of bravery in the battlefield. People like Sergeant York, George Washington and et cetera. But it seems like these two most recent wars we’ve been involved in, the Afghanistan war and the war in Iraq, we don’t really have those sort of superstar heroes. But the thing is there is some really heroic things going on. There are some men who are doing just amazing things in just dire situations.

And our guest today wanted to find out why that is and he wanted to correct that. His name is Mark Lee Greenblatt and he is the Author of the book Valor: Unsung Heroes from Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Home Front. And in today’s podcast Mark and I talk about like why don’t we know more about some of these brave men who are fighting overseas and some of the things that they’ve done. And then we talk about some of the men that he writes about in his book and what they did and their acts of bravery, the valor that they displayed. And then we also talk about what lessons we can learn from these men. So it’s a fascinating podcast. I hope you would tune in. It’s going to be a good one.

Mark Greenblatt, and welcome to the show.

Mark Lee Greenblatt: Well thanks so much for having me on Brett. I got to tell you before we start that I am such a huge, huge fan of the Art of Manliness. I listen to the podcast all the times. Steve Pressfield’s interview was great about the Turning Pro and Battle of Thermopylae and everything like that. It’s just – this is great. This is one of my favorite things to listen to. So it’s a real honor to be on.

Brett McKay: Well thank you very much, I’m very humbled. So your book is called Valor: Unsung Heroes from Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Home Front. First of all like what inspired you to write this book?

Mark Lee Greenblatt: Well back in 2007 and 2008 I went to these awards banquets where they honored military heroes. And they would recite the stories of what these men and women had done and they were just unbelievable. And there was not a dry eye in the house at these big gallo events. And everyone is crying about how amazing, how inspirational they were. And I remember thinking to myself, how come no one knows these guys, how come – they will be lucky to be bagging groceries if they get a job in the first place, whereas in the past war heroes came home and they were household names and we had ticker tape parades for them in their communities and we’ve really got away from that. And I set out to change that. I said these people – we need to know their stories, we need to know their names and that was really the moment when I said this is something I’ve got to do.

Brett McKay: So – and why do you think – I was wondering that too. As I was reading these stories of these men in combat, I get to wonder like why I haven’t heard about these guys. Because you hear there is a few that I know about, but for the most part I don’t know. And like in fact you’re right like back in World War I and World War II, war heroes were household names like – they even make movies about them like during the actual war while the war is still going on, ticker tape parades. So why is it that these past two wars, the one in Iraq and Afghanistan failed to produce the superstar warriors? Because it’s not anything that the men have done like they’re doing heroic things, but something is going on in the home front that’s not allowing that to happen.

Mark Lee Greenblatt: Right. I think it generally boils down to two or maybe more factors. But the two that pop into my mind instantly are politics and the focus of the media frankly. These wars were generally very political, particularly Iraq. And if you think back to those days, 2005, 2006, 2007, those are dark days I think in American history particularly when you talk about the wars. And the debate was really frenzied and really nasty. And amidst to that turmoil, I think stores of selflessness became passé.

Heroes were sort of old news and it was sort of romanticized to go the other way and find the stories that were bad. And that was the balance that I was trying to fix. I felt that it’s got out of whack that people would know very few American soldiers who are serving overseas and the few that they did know where for bad reasons. Like Lynndie England in the Abu Ghraib Scandal or for controversial reasons like Pat Tillman or Jessica Lynch. We had no one that was just by Audie Murphy or Sergeant York in World War I. And that was exactly the void I was trying to fill.

And the other thing was the media. I think there was showing these kinds of story, these positive stories were viewed in the media as being biased in favor of the war and sort of propping up the Bush administration at a time when that was I think very passé. And so I think that was – those two things really created an atmosphere were stories of heroism just got lost.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Do you think we’re also as a culture uncomfortable with violence for good purposes? I mean even it’s used for good, do you think we’re sort of uncomfortable kind of lauding war exploits?

Mark Lee Greenblatt: I think as a part of that, I would say that there is violence all around us. I mean you look the at movies and video games, in a way we’ve become desensitized to that sort of violence. But I think there is also another factor that might be a play which is that we have a bit of a disconnect between the folks who serve and their families and the folks who don’t. And I think that disconnect, back in the day everyone knew someone who is serving. It was either the guy down the block or someone in your own family whereas now I think there is a chasm between those who are serving in those and those who aren’t. And so those folks don’t have it in front of them and aren’t so committed to knowing these stories and publicizing these stories. And so I think that’s a third factor that really goes into why these names are not household names like in years past.

Brett McKay: Okay. I think I remember reading and maybe I read this incorrectly, but do we give fewer medals for valor during the two most recent wars than we did in previous wars and if so why is that?

Mark Lee Greenblatt: Yeah. I don’t know about in total in terms of all of the medals, but certainly with respect to the Medal of Honor which is the one that gets the most notoriety, I mean the most attention and really kind of frames the perception of these things in the American public. Certainly those are way off. In World War II I think it was, it was one per 35,000 and in the last two wars it’s something along the lines of one per every 115,000. So it’s dramatically different. And part of the problem is the nature of the battles that we’re facing, at least this is what I’ve read is that DoD regs say that the Medal of Honor has to involve enemy combatants. And so when someone does something heroic in the face of say an IED attack, there is no actual enemy combatant. And so for a while I believe that held up or at least it skewed the Medals of Honor versus in previous combat. And I think there is an effort to change that or review that, because that’s really kind of changing the numbers and therefore changing the perception of the wars in the way they were talking about.

Brett McKay: Okay. Another thing as I was reading this reminded me, because before I read Sebastian Junger’s War and then your book reminded me of it is just the tactical difficulty of these two most recent wars. And I think a lot of Americans understand what the – what our fighting soldiers are facing and what they faced over those and some case still facing today. How were the two most recent wars different from previous wars that we’ve been in?

Mark Lee Greenblatt: Well I think the big thing is that we’re not fighting a known enemy in the sense that they’re not wearing uniforms and they’re not using sort of typical battle tactics. They’re just popping up as snipers in the middle of the street and using IED’s in a way that I think is different from previous engagements, at least on the scale that we’re seeing. And that has – had a dramatic impact.

The – one thing that the impact on the guys is that you can never really let your guard down. We’ve had so many infiltrations where purportedly friendly forces are then turning their weapons on Americans that our guys can’t really put their guard down. So there is no downtime and that keeps them on edge for long, long periods of time. And so I think that has over the long haul a really detrimental effect.

At least what I heard was that it was – that was really hard just keeping your mind engaged at all times. I mean that goes – that gets old after a year long deployment. And so I think that change is really having an impact and that’s hurting them when they come back. I think that’s very difficult for them to deal with when they come back, because they’re always on edge, always looking for a long period of time looking around the corner, looking in that – at that debris in the street wondering whether that’s an IED. And so when they’re walking down the street in their hometown they were reminded of these things and sort of show constantly on the rain. And I think that gets – that weighs on them and that really has had a dramatic impact.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And I mean I guess the Iraq war is a little more of a traditional war where there was an army perhaps, but like the Afghan – the war in Afghanistan, that was just crazy. I mean first off Afghanistan is like – just the environment there is just crazy, it’s one of the most harshest places on earth and then you have like these – you describe these – some of the encounters and they happen in these little small villages that have these winding goat trials and you – I mean you don’t – you really can’t see what’s coming at you. I mean it’s just really – when I was reading that I just – I couldn’t imagine being in those guys’s place.

Mark Lee Greenblatt: Yeah, that’s right. And I think the other thing is that if you think about World War I and World War II, our guys were going over to Western Europe. They can appreciate Western Europe. They may not speak the language, but they know what a bakery looks like, they know what’s going on in the streets, in the signs and they can get some semblance of what’s happening, whereas when you’re in a rural village in Afghanistan that is as far away as you can get. I mean one of the guys that I interviewed described the landscape is like walking on the moon. He was like literally in a different place in the universe from what he was familiar with.

And I think doing that over and over again with languages that are so different and the cultural experiences are so different, I mean they couldn’t really relate the people, the goat herders that they were interacting with. And I think that really overtime just really weighs on the guys in a way that’s different from previous wars where it’s – so you can understand the terrain better, your brain is working less actively, because you know what the church looks like and that sort of thing. And so I think that has another impact as well.

Brett McKay: So we will get into some of the specific stories here in a bit. But before we do that, what did all the men who you included in your book have in common? Or I mean I guess what I’m saying is what trades gave them valor or made them a hero?

Mark Lee Greenblatt: There are two things that really emerge. One is the sense of brotherhood, the selflessness, this team work. It’s overwhelming when you talk to these guys. And the nine that I profiled, but also the other folks that I interviewed, the other men and women that were in the stories, the sense of brotherhood is unlike anything we see in civilian life. I mean the willingness to do anything; literally anything to save your buddy is just – it’s sort of all inspiring. And I mean that in the actual real way like inspired all in me that they were so willing to do anything for each other. It is just a fascinating characteristic that I tried to convey to the readers. I really tried to put them in their minds and convey that just their willingness to do something, because I don’t think we can appreciate.

The second thing is in each of the stories the men had these moments amidst the males from going on around them where they were in relative safety. And what I mean by that is like the bullets weren’t firing directly at them. They were inside the building when the shops were being fired in the alley way immediately outside, that sort of thing. But in each of the stories, the heroes decided to put themselves in greater danger. They left that position of relative safety and put themselves in greater danger in order to save a life or accomplish a mission. And that moment was fascinating to me.

I had to find out more about that. And so I really slowed downtime and I was asking these guys minute-by-minute, second-by-second what you’re thinking then, what’s happening then, what’s happening then and try to place the reader in their bodies, in their minds as these dire circumstances are unfolding and say what is making you think about going into that, into the sniper’s fire or jumping into the swirling water in the middle of the Atlantic, in the middle of this horrific storm. What’s making you jump in there and do that and that was just a fascinating moment and that was what I tried to capture for the readers.

Brett McKay: Well you did a good job capturing both the brotherhood and why these men made the decision that – and yeah, I will be honest, when I was reading to these stories talking about brotherhood and some things we talked about on the side before like talking about honor, all right, this idea that you – it’s all about caring for your brotherhood and being concerned about your status within the group and that means putting the team before you. And that was another common threat to all these guys like it was the team before self…

Mark Lee Greenblatt: That’s right, self-sacrifice, yeah.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And as I was reading these stories like I will admit like I was like man, I want to signup just so I can experience that sort of brotherhood, because like I’ll be honest I don’t think I’ve ever experienced anything like that or close to it. Maybe something is on a small magnitude, but I’m sort of envious in a way of these men who had that experience. I don’t envy like the – being in – having to worry about IED’s, but I envy that sense of commodore and brotherhood. And I think a lot of men probably want that in their life too.

Mark Lee Greenblatt: Absolutely. I mean I thought the exact same way. There is that envy that you’re just like wow that is so captivating that you can be part of something that you would literally die for. I mean that is just mind-boggling and I was so inspired by that. And one of the stories involve the guy named James Hassell who literally a mortally injured guy through crossfire and both of them said they weren’t particularly close. It wasn’t like they were best friends, it wasn’t like they had grown up together, it wasn’t like they were soul mates or anything like that. But James was like that’s my team mate and I am not going to let him die.

And Chris Kyle, one of the Navy Seals, he didn’t even know the guy that he saved and he put himself in extraordinary danger, literally liberating a group of marines he did not know and single handedly pushing off in sergeant snipers to liberate them. I mean just a captivating moment and he didn’t even know them. It was just that sort of generic team that he was a part of and I just found that just so overwhelming.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I mean I love the idea that self-sacrifice forces you to – when you’re doing something for others you push yourself beyond your limits I feel like. So I feel like in America at least right now there is a sort of idea that I want self-fulfillment, I want to become the best me and it’s all about doing stuff for yourself, all right. You do like you meditate or you exercise, but you don’t really do it for anybody else. But like in my experience when I’m doing something, when I’m trying to serve another person, whether it’s my family or the people I write for like that pushes me beyond what I think I’m capable of.

Mark Lee Greenblatt: Absolutely and that’s born out in all of these stories. I mean it’s exactly that. They’re willing to do more for someone else. One of the guys, James Hassell, the marine I was talking about earlier, he said that the fear wasn’t dying himself. He was sort of over that. The fear was that he would do something wrong or did not do enough and then that would result in someone else, another marine dying. He said that was the motivation to do anything. It wasn’t about himself. He said if I died, but I saved other marines in doing so, I would be successful, I would be happy with that. And it’s just a mind-boggling concept and that was something that’s just so inspiring and in fact clearly what you’re talking about, they’re willing to do so much more on behalf of their team mates than perhaps for themselves.

Brett McKay: Yeah. That example right there is a perfect example of just traditional honor, right like you – it’s all about – it’s all about the team, that’s what honors. And I think in America and in the west like we – most civilians don’t understand that sort of honor. Like for us honor is like integrity, personal integrity. I live by my code. But honor in the sense that what the Roman’s talked about and what Theodore Roosevelt talked about, that still exist in combat today. It’s really cool. Here is a question I have. How did you get these men to open up about their stories? Because most soldiers, particularly ones who have been awarded medals or distinctions for combat or for valor, they’re very hesitant to talk about it, they’re very humble, they will just say things like oh I was just doing my job, but you stories are very detailed like you said. So how did you get them to open up and talk?

Mark Lee Greenblatt: Well first of all I should say none of them wanted to tell their story. They all said exactly what you’re talking about. I’m not a hero. I did what anyone else would have done. I just happen to be in the right place at the right time. And frequently they said I’m not the hero, it’s the guy next to me that was the hero. So I mean it’s just stunning how – and they really believe it by the way that this was not some sort of like talking points that they have. They really genuinely believe it and so they bristled when I would use the term hero. In fact I frequently would not use the term hero or heroic or anything like that. I would just say it’s pretty cool what you did and can you tell me about it.

But in order to get them to participate in the project, it was very difficult. I basically had to beg and please with them and to get them to tell their story. And what I told them was – and I wasn’t playing faster moves or anything like that. I was very obvious about it. I said look these stories need to be told and it’s not about you and your story, it’s about using your story as an example for what everyone is doing, for what all the 10s of 1000s of men and women are doing overseas. And in order to spread the word about what all of you are doing, I need to tell some stories and yours is one. And I think they believed in that.

Again it was shifting it away from them as an individual and more about the group and they believed in that. And the other thing was that I told them that I’m donating a significant portion of the proceeds to military and veterans related charity. So I think that helped them get over the fact that they were – didn’t want to hold themselves out as being exceptional, but they would do it for a better cause maybe. So I think that helped.

But in terms of like actually sharing the details which I think is part of your question as well is I’m a trained investigator, this is what I do for a living. I’m an attorney and I conduct investigations and I’ve done that for a long time. And so these were akin to depositions or witness interviews that I’ve done a large number of times. And so what I did was I treated it like that where I would interview them and drill down into the details and extract as much information from them as possible. And one of the guys told his wife, this guy doesn’t get it, he keeps asking me the same question over and over again and that’s one of my standard tactics is keep asking, keep asking, there is always more there. And that was it.

It was basically deposing them and asking them difficult questions and I will give them all – huge credit because they all stuck with me. They all answered my questions. They never said no. They never bristled at the questions. There was a lot of crying. There was a lot of very difficult moments crying by them, crying by me. I was so moved by what they were telling me. I mean these stories of individuals literally dying in their arms, I mean you get chocked up just tearing it and it was really emotional. There are also some really funny moments too. I mean some laugh out loud funny moments where I had to stop the recorder for a second, because I was chuckling so loud. So anyway, it was just a wide range of emotions. But getting the details from them was no easy feat, let me tell you.

Brett McKay: Well I’m glad you’re persistent, because I feel fortunate to have read these stories. So let’s get into give people a taste of what’s in your book. Are there any stories in particular that stand out to you or where some of your personal favorites. I know it’s like picking children, but what’s something – what’s a story in the book that you particularly like?

Mark Lee Greenblatt: Well yeah, as you said it is like picking children. I couldn’t possibly like – folks would ask me do I have a favorite, no. There is – I mean I love them all and I do actually have some level of love for these guys. I mean I feel a kinship with them. But there are couple of stories that are interesting on multiple different levels and I think that’s what gets me a little bit like one guy Mike Waltz, he was a Special Forces Commander, a Reserved Special Forces Commander who is leading a squad in a very remote village in Afghanistan. And they had words there were insurgents there and Mike was leading his squad through the village doing a regular petrol. And they had been paired up with an Afghan unit.

And Mike had grown to really admire the Sergeant Major of the Afghan unit and that this guy Sumar and he really respected him and he got to know him and he asked Sumar, he said why are you in the army putting yourself and your family at risk. And he said essentially that he was doing it so that he could give his children a better life and have his sons earn enough money so their sons wouldn’t have go to the madrasahs where they would get fundamentalized, radicalized. And so Mike grew to love this guy and it was really interesting and they had developed this sort of relationship even though they are going through an interpreter this whole time.

And fast-forward to the next day and they’re on a patrol and there is an ambush and machine guns mowing them down. And Mike stands up and he is literally firing against these two machine guns that are very, very close, essentially point-blank range. And mike is standing there in the middle of this riverbed shooting back at them with just a pistol. He is not wearing his helmet, he doesn’t have any grenades and he is firing back with a pistol. I mean it’s just – you get the image in your mind, it’s unbelievable. One of the medic that was in his unit who was standing there watching all this said when he looked from his perspective, they were so close that the fire from the machine guns and from Mike’s gun where essentially touching. That’s how close they were.

And just captivating this moment, but then here is the part that gets even better. So Mike eventually goes for dice, a cover behind this little tiny stone wall and he saw that Sumar had got shot. And so he runs out into the kill zone, right. The insurgents could start firing at any moment, but Mike runs out into the kill zone and grabs Sumar and he is dragging him back into behind this wall trying to protect him. And as he is dragging him Sumar – he hears his last breath, he hears Sumar die in his hands, in his arms and it was obviously a tragic moment. Fast-forward a bit, they survived that firefight and Mike later heard that Sumar’s family had to send their kids to the madrasahs because they couldn’t afford the other schools.

And so Mike on his own spending his own money began to support Sumar’s family. He would wire money, figured out this way to wire money to a remote Afghan family in order to pull those boys out of the madrasahs so that they wouldn’t be radicalizing even more kids. And Mike has been giving the money for years now and he has never met them. He just knew Sumar. And I just found that so captivating not just the fact that he was fighting against these machine guns at essentially point-black range with a pistol, but that he would do all that. He would run back in and save – try to save Sumar’s life and then literally supports the family on his own, his own money. I just found that overwhelming and it’s just so inspiring.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I knew, that was one of my favorites. All of them are great, but that one really touched me. But yeah, I mean there is just – there are so many, so there is how many, there is nine total stories?

Mark Lee Greenblatt: Nine total and I can talk about each one of them like – I mean it’s just – the thing about supporting the family just kind of kicked it up a notch that if anyone – if folks are going to hear about any one story, I think that’s a good one to hear about. But I’m happy to talk about the others, I mean one of the guys, we’ve talked about James Hassell earlier and Marine Grunt who is an awful firefight in Jaffe and one of his comrades like I said was brutally – I mean awfully injured by a shrapnel from one of the insurgents and they knew he was going to do die if they didn’t get him to the medevac unit, medevac unit was about 100 yards down in alley. The problem was there were insurgents shooting directly into that alley.

And so they said we got to get Ryan out and James reached his hand up and said throw him on my back, that’s what he said. Right then and there is no hesitation. And that’s what they did and James as he is about to leave this building, go out into the crossfire where insurgents are literally shooting right down where he would be running, he fought back to a promise that he had made his mother that he was going to come back to her from Iraq in one piece and he actually thought to himself at that moment, I’m about to break that promise. He thought he was going to die, but he wasn’t going to let Ryan die, he was at least going to give it a shot. And that’s what he thought as soon as – and just as about as he is going to run into this alley and then he goes and he runs down and I tried to slow down the time and present each step essentially as he is running down this alley.

And long story short, he saved Ryan’s life. He literally saved Ryan’s life by carrying him down that alley to the helicopter and to have these amazing moments I had this interview with Ryan about what it was like to be carried on James’s back as the bullets are raining out. And he was pretty sure he was going to die not just from the shrapnel, but from getting shot. Just the moment of when they turn the corner away from the shooting, just a celebratory moment was pretty cool. It was a pretty good story and as you know because you’ve read the book, it’s got a bit of a tragic ending.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Mark Lee Greenblatt: Because James after he left the marine core came home and at 30 years old out of nowhere he just collapsed on his kitchen Monday over a Labor Day weekend and tragic, tragic story he never came to. And his wife, he is survived by a beautiful wife and lovely four-year old daughter. It’s just a tragic story that he could do something so heroic, so amazing overseas literally saving lives, but then he had his life tragically cut short and there is an amazing coda on top of that frankly that he was an organ donor and his wife just told me not too long ago that James’s organs where then donated to a number of people that he – she heard back that his organs actually saved four people’s lives. So even in death James Hassell was saving lives, pretty incredible, pretty inspirational.

Brett McKay: That’s amazing. Well I mean we could talk about each of them, but I don’t want to, because I want people to go out there and get your book and read these stories for themselves. I can imagine that talking to these men and then writing their stories down has changed you. How has writing this book made you a better man?

Mark Lee Greenblatt: A couple of different ways. There are lessons from these guys and I’ve really tried to incorporate them. One of them is perspective frankly, a couple of these guys, I mean all of them believed they were going to die at some point during the stories that I tell, the incidents that I described. And I think about – I actually think about what they were going through in my moments of stress. And they seem so small, so patty.

There was one guy who – Dan Foster, who single-handedly held off an insurgent ambush of his little remote outpost and he had suffered major, major injuries. And he looked at a mirror at one point back in the medics tent and he saw this awful injuries to his face, he lost his teeth substantial bone structure and his upper and lower jaws, I mean it was a disaster, it was awful. But Dan went back into the fight after he saw those injuries in the mirror. And so when I’m having a difficult time with my first world problems, I actually think about the moment that Dan Foster looked in the mirror and went back into the fight. So when you ask how have I changed, how has this improved my life, I think I’ve got some perspective where before as my wife and I went down, I would get really pissed. But now I actually think about Dan Foster and I try to get a bit of perspective on the situation that my problems aren’t so bad.

And I think about these guys, Chris Choay in Afghan, I mean a army paratrooper who is in Afghanistan earned a silver star at one point did something truly incredible and he called it the loneliest moment of my life. He thought he was going to die and I think about that when some idiot cuts me off in track and all that I lose my cool. I actually think about Chris Choay about how he can lose his cool in the loneliest moment of his life and he thought he was going to die and he then preceded to do something incredible and heroic. I actually try to think about those guys and incorporate their experiences in my life to make me a better person. And I think that’s a good lesson for all of us frankly. A bit of perspective really will kind of make you reduce the stress, make things roll like water off a duck’s back a bit more in our lives.

Brett McKay: Very good. Well our time is coming to an end. There is so much more we could talk about, but where can people find out more about your book Valor?

Mark Lee Greenblatt: On my website, markleegreenblatt.com and one very cool feature about it which I invite everyone to use is I have set it up that folks can go on and email directly with the heroes. So they can email the guys that we talked about, Mike Waltz, Chris Choay, all the folks we talked about. And for the – there are two of them, James and Chris Kyle passed away since they returned home, but folks can email their families. And what – I would invite people to reach out and share their thoughts about hearing their stories and feel free to ask questions or even if they just want to say thanks. These are great guys and I know they would want to hear from people. And I think they will interact. So I would invite you to go on and shoot them an email and you will probably get a response.

Brett McKay: That’s awesome. Mark Greenblatt, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Mark Lee Greenblatt: Thanks so much, Brett. This has been great.

Brett McKay: Out guest today was Mark Greenblatt. He is the Author of the book Valor: Unsung Heroes from Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Home Front. You can find that on amazon.com or bookstores everywhere. Also make sure to checkout his website markleegreenblatt.com and you can actually email some of the heroes that he highlights in his book Valor, a pretty cool thing. So that’s markgreenblatt.com.

Well that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to checkout the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. And again if you enjoy this podcast, you’ve got something out of it, I would really appreciate if you take the time to give us a review on iTunes or to Stitcher or whatever. That would help us get the word out about the podcast and let more people know about, so yeah please do that. Until next time, stay manly.