We all know people who have a certain magnetism and charisma. What is it exactly that makes them so compelling?

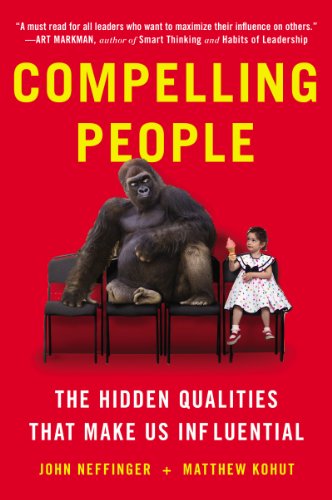

My guest today explores that question in his book Compelling People: The Hidden Qualities That Make People Influential, and primarily locates the answer in two such hidden qualities: strength and warmth. His name is Matthew Kohut and today on the show he explains why it is we find the combination of strength and warmth so attractive in others, and how we can cultivate these traits ourselves, including in the way we dress, carry ourselves, and talk. Matt then gives advice on how to display strength and warmth in different situations we might find ourselves in, from acing a job interview to managing a crisis at work. We end our conversation with that most perennial question of body language: what to do with your hands when you speak.

Show Highlights

- The relationship between strength and warmth in charisma

- Why do we respond positively to strong people?

- What does it mean to be “warm”?

- Are there downsides to warmth?

- How to assess your own warmth-strength meter

- The matrix of how the relationship between these two qualities play out in real life

- How context determines whether to display more warmth or strength (and how to figure it out)

- The importance of your posture and appearance

- Conveying strength when you aren’t physically large/imposing

- The value of non-verbals: our smile, eye contact, etc.

- Cultivating “unconscious competence”

- Showing vs telling that you understand people

- What do you do with your hands when speaking?

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- 5 Ways to Build Your Personal Magnetism

- The Charisma Myth

- How to Be Assertive

- A Study in Charisma From Tender Is the Night

- Our series on the 3 elements of charisma

- Difficult Conversations, Small Talk, and Charisma

- AoM’s social skills archives

- The Misunderstood Machiavelli

- Using Body Language to Create a Dynamite First Impression

- The Ultimate Guide to Posture

- AoM’s style archives

- Dressing Taller: 10 Tips for Short Men

- How to Make Eye Contact the Right Way

- Robert Kennedy’s speech after MLK’s assassination

- How to Improve Your Speaking Voice

Connect With Matthew

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Recorded on ClearCast.io

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Collection by Michael Strahan. Makes it easy to look good and feel your best no matter the occasion; includes sport coats, dress shirts, accessories, and more. Visit JCP.com for more information.

Policygenius. Compare life insurance quotes in minutes, and let us handle the red tape. If insurance has frustrated you in the past, visit policygenius.com.

Saxx Underwear. Everything you didn’t know you needed in a pair of swim shorts. Visit saxxunderwear.com and get $5 off plus FREE shipping on your first purchase when you use the code “AOM†at checkout.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: We all know people who have a certain magnetism and charisma, what is it exactly that makes them so compelling? My guest explores that question in his book, Compelling People: The Hidden Qualities That Make People Influential, and primarily locates the answer in two such hidden qualities, strength and warmth. His name is Matthew Kohut, and today, on the show, he explains why it is we find the combination of strength and warmth so attractive in others, and how we can cultivate those traits ourselves, including the way we dress, carry ourselves, and talk.

Matt then gives advice on how to display strength and warmth in different situations we might find ourselves in, from acing a job interview, to managing a crisis at work. We enter a conversation with that most perennial question of body language, what do you do with your hands when you speak? After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/compellingpeople.

Matthew Kohut, welcome to the show.

Matthew Kahut: Thanks for having me.

Brett McKay: So, you are the co-author of a book called, Compelling People: The Hidden Qualities That Make Us Influential. What got you started researching, what makes compelling people compelling?

Matthew Kahut: Well, my co-author, John Neffinger and I, and a third partner, Seth Pendleton, we came to this through politics, actually. All of us were speech writers, we were working with different folks. And full disclosure, we’re Democrats, and we were watching people lose, in the early 2000s here. And we were trying to figure out, how do we make messengers more effective in that setting? And it led us really on a journey to try and figure out how people got the thing that we call the it-factor. This idea of charisma, or whatever it is you see when you sense that somebody is a very magnetic presence. And around the time we were trying to figure this out, and doing some speech writing for some folks, we also started working with some first clients, and it led us to identify two fundamental problems that clients would have.

Some of them were really towers of strength, in the sense that they were incredibly capable, but they were cold. And that was one set of problems. And then, on the other side, we’d see these people who were the nicest people in the world, but they were always tripping over themselves, and apologizing for themselves. And we saw this again and again, in this early client work. We were sometimes doing things for free with people, and getting friends who were just having problems communicating. And we noticed these two things happening. And we were also research geeks, and we were talking to different behavioral economists and reading social psych. And we looked in the research, and we found an answer that essentially supported our hypothesis, that there was really something there about these two fundamental qualities that we were identifying as problem areas for a lot of people.

Brett McKay: So, yeah, you just make the case that strength and warmth are these two things that people look to, when they’re making judgments of people. Because sometimes we think, oh, when you make a judgment on a person, there’s like one thing you’re looking at. But you say, we’re making two separate judgments on whether they’re strong and warm.

Matthew Kahut: Yeah, that’s right. And in some way, you can think about it almost, I’m going to go pseudo-evolutionary biology here. You see somebody coming over the savanna, far off on the hill, and you look at that person, you think, “Is that person a threat? Is this person, maybe, an ally?” And we make these kinds of judgments all the time. We look at people’s capabilities and their intentions. And we say, “What can this person do? And are they my kind of person?” And so, it’s interesting that we chose the word strength and warmth very deliberately. And yet, in the years that have followed, sometimes I find that talking about capability and connection, is also just as accurate a way to describe these qualities. Because, ultimately, it’s showing people what can you do, and do you care about the same things I do? Are we on the same page, in some way?

Brett McKay: Yeah, I think this is great that, I mean, you came from this in the political perspective, because politicians, from the very beginning, have been balancing these two factors. Like, why politicians, they want to appear strong, but it’s like why they kiss babies, right? When they’re on the campaign trail.

Matthew Kahut: Exactly.

Brett McKay: Because they want to appear warm. Or, it’s like, they’re like, you want to be the guy that you can have a beer with, right? That’s relatable.

Matthew Kahut: Right, sure. Right. And that relatability factor is why people eat fried dough at county fairs, and do all those kind of things you were mentioning.

Brett McKay: Even though they hate it, and you can tell they just not want to be there. All right. Let’s talk about these two attributes. What do you mean by strength? And why do we respond positively to strong people?

Matthew Kahut: Well, strength, the easiest way to think about it, and again, if the word capability works better for you, use that. But, think about it as a combination of your skill, plus your will. The academic words that we tend to connect to make this concept are competence and assertiveness. And not to go too far down the rabbit hole here, but, the academics, who have looked at these two qualities, they really focus on competence and warmth. John and I, in our practice, we were really seeing something more than that. Competence alone doesn’t really explain what we respond to in people, there is a facet of our will, that’s in here. The assertiveness side of it. In other words, you can probably think of people who are really competent at something, but they don’t speak up for themselves. They don’t put themselves out there.

So, we combine these qualities, and hit on this idea of strength or capability, as the thing that really matters. And at a fundamental level, strength says, you can get things done. It also says, you can protect yourself and you can protect others. And that’s part of what’s really attractive about strength, is, when we see somebody who’s either very capable at something and we admire their capability, or that ability to protect. That’s a very positive thing. Now, there’s a downside to strength too, which is that strength can be used to get things done that you don’t want done. When you see someone else using their strength in a way that is not to your liking, they don’t share your intentions, then you look at that strength and say, “Oh, my gosh. Yikes.” And there, it can elicit a fear response, when it’s all strength, no warmth.

Brett McKay: And you also highlight in the book that some people are skeptical of strength. They’re like, “I don’t know about that.”

Matthew Kahut: Absolutely. So, when you think about… I’ll go traditional here, when you think about, let’s cast our minds back 50 years, it’s the anniversary of Woodstock here. Think about hippies looking at the establishment, back in the 1960s. And this is on the backdrop of the Vietnam War, and all those kinds of social factors. There was a very skeptical view of what you might think of as traditional strength at that time. And you can argue rightly so. And it’s a very interesting dynamic. There are people who, almost as a disposition, are skeptics about what you might think of as traditional strength displays. And I don’t mean to say that they’re all hippies, there are plenty of people who share that disposition of all sorts of stripes, politically. But, it’s an interesting thing that you see.

Some people, when they see a person posturing in a way that is traditionally perceived as strength, given whatever culture you’re in, they’ll give it the hairy eyeball and say, “What are you up to?” And they won’t necessarily believe it’s anything more than that kind of a posture. Or, they might even just reject the posture on its face.

Brett McKay: So, what goes on our body, when we display strength?

Matthew Kahut: Yeah, well, I mean, the key hormone where strength is concerned is testosterone. And that’s not a secret. And it’s also about, one of the things that people tend to associate strength with, on the physical side, is taking up space. And so, when you think about how you feel when you are triumphant, when you’re taking up a lot of space, while you’re doing those kinds of things, your hormones are shifting too. And people who have just been in some sort of a more triumphant kind of a setting, feel more confident, and their hormonal balance is shifting as they’re doing these things too. Where, we’re never at rest, hormonally, we’re always doing something. And for sure, there are different effects that kick in, depending on what behaviors we’ve just had.

Whether we’ve just been victorious, or felt like we did something really well. Or, if, on the other hand, we’ve just experienced some sort of a setback, or, are feeling downcast or dejected.

Brett McKay: All right. So, strength is competence and will, what does warmth look like?

Matthew Kahut: Warmth is very context based. I think the easiest way to think about warmth is showing people that you share their concerns, their interests, maybe even their emotions, depending on what’s in play. And that can include values as well. And like I said before, a lot of times, I talk about a sense of connection. Because, warmth is, it can both be biological, in the sense of the way we feel around the people who we’re closest to. Think about parents and their children, there’s that warmth that is really something that begins with skin to skin contact between mothers and infants. And then, there’s also this sense we have with people we know in a more broadly social way, of just having things in common with them.

And we feel that they share our perspective in some way, or they see the world through a common lens with us, even if we don’t agree with them about everything. And, for most people, most of the time, walking through life, I find that’s a more user friendly definition of this. It’s that sense of connection, where you see the world through a common lens, you feel like, “This is my kind of person.”

Brett McKay: So, the downside with strength, is that, it can be looked at with suspicion, or it can be, you’re using it the wrong time. There’s downsides to too much warmth, right?

Matthew Kahut: Right. So, the extreme of warmth is, the nice guys finish last. This is kind of Charlie Brown with Lucy pulling the football away from him, if I can use an old cartoon metaphor here. It’s essentially that you can come up cross as the lovable loser, or, at the extreme, somebody who elicits a pity response. If you think about somebody who’s super, super nice, but they just keep tripping over their own shoe laces. At some point, you’d say, “Oh, that’s too bad about him.” And that’s sort of all warmth, no strength, at its extreme.

Brett McKay: And what’s going on with our biology, when we’re displaying warmth?

Matthew Kahut: Well, the primary hormone that’s in play with warm is something called oxytocin. And it’s this feeling of togetherness with other people. Some people call it the empathy hormone. And it’s not just about that, I want to be clear that oxytocin is something that we feel when we’re with people who we’re very connected to. Oxytocin is a complex hormone, it’s also the thing that makes us strikeout of people who are outside of our tribe, so to speak. So, I want to be clear that it’s not just all warm and fuzzy, but it is absolutely what we’re feeling, when we get the warm and fuzzy with other people.

Brett McKay: So, warmth is our ability to connect with others. Are we able to be both strong and warm, at the same time? Display competence and will and connection, at the same time?

Matthew Kahut: It’s really hard, let’s put it that way. John and I hit on the idea that it’s like multitasking. In the sense that, you’re never truly doing two things at once, you’re shuttling back and forth between them. And the same is true with people who are doing the strength and warmth in the same appearance, if you will. So, when you’re with somebody, and you sense their capability, and then, you sense their sense of connectedness with you, or vice versa, that’s the better way to think about it, is, different situations, even within the same meeting with somebody, will, in some way, offer you a chance to show them your capability, and, or, your sense of connection to them.

And it’s much more likely that you’re going to have a chance to show both, one after the other, or back and forth. Then, that anything would happen, where you would just be able to nail it, so to speak. First off, it’s very hard, because there’s a balancing act between these things. They are intention with each other. And realistically, the situations that come up, typically ask you to show one, more than the other, in any given moment.

Brett McKay: You call it like there’s like a hydraulic factor going on between the two. Like, one goes up, the other goes down.

Matthew Kahut: Right. That’s exactly right. The more strong you seem, the less warm you seem, and vice versa. And so, that’s why, if you’re cognizant of these things, and you know your own tendencies, then, it can be helpful to keep an eye on, “Hey, have I overexerted here on the strength side?” I have to remind people, “Look, I’m on your side,” or vice versa. And it’s not that you’re doing this in some high self-monitoring way, so much as you’re just being emotionally intelligent with people, and making sure they don’t lose sight of these things, where you’re concerned.

Brett McKay: You mentioned earlier, that, you alluded to it. There’s like a spectrum of strength, plus warmth combinations, right? If you’re just super nice, all warm, no strength, that elicits that pity response from people. I mean, what are some other combinations on that, I guess, it’s a matrix that you’ve developed?

Matthew Kahut: Yeah. So, this two by two, which came out of some of the academic research, was, it’s something that it’s fun to play with. So, if you think about yourself, and your combination of strength and warmth, as something you can plot on a two by two graph, then, here’s one way to think about the thought experiment. And then, I’ll get to your question about the combinations here. So, if you ask 10 of your friends, “Hey, here are these two qualities, strength and warmth. How would you put a dot for me on this two by two here?” And then, you average those dots. That gives you a pretty good idea of where you stand. None of us are great at seeing ourselves, as others do.

But, if you had 10 of the people who knew you best, put a dot on that thing, and then, you average those dot, that would give you an idea of pretty much how other people are seeing your combination of showing them that sense of capability and connection, or strength and warmth. Now, as far as archetypes that fall between these things, it gets granular at this point. It’s almost like thinking about young archetypes or something. One of the things that I found, talking about this with people, since the book came out, is that, there’s a category of people who oftentimes are subject matter experts. Who, while they’re doing strength more than warm, the strength they’re doing is really about competence. And it’s not this kind of domineering, assertive strength. They’re doing a lot of subject matter expertise. There’s typically really, really smart people, who are really invested in what they do. And they sometimes have warmth challenges, but they are fantastic at the competence side of strength.

Now, another side of it is the person who is the bully, essentially. Who’s domineering. They may not know much, but they’re great at just pushing people around, and they can lack that warmth. Those are some of the gradations on the strength side. On the warmth side, where you have some degree of capability, but you have people who are helpers, for instance. Their instinct is to do for others, and they’re the person who maybe the go-between with people, the person who is always mediating or facilitating interactions among people. That’s something you can see with someone who is more warm than strong, but they’re also, they’re not deficient on the strength side. And you have people who play roles that require a little bit more of one than the other.

It’s hard to generalize about people in different combinations too much here. But, when you think about people doing things like teaching, or doing things like parenting, both of these qualities are acquired in these roles. And it’s worth thinking about, how are you navigating these things? Rather than thinking about archetypes that you see in the four quadrants. It’s almost more interesting to think about the roles you’re playing, and how they might require some of each.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And I liked that you had this matrix, and you talked about different responses you give to people. Because that was useful for me. So, you talked about someone who’s low on warmth and low on competence, or low on strength. Those type of people, they’re just really annoying. Right? So, you have contempt. But, you know those people that you’re just like, “God, jeez.” He’s not useful for anything, and he just, he aggravates you. Everyone’s had that person in their group. So, yeah, that’s low warmth, low strength, that you have contempt, or you’re just annoyed by them. High warmth, low strength, that pity response. High strength, low warmth, that could be in view of fear. And then, the sweet spot is high strength, high warmth, and that sort of admiration. Like, that person has prestige.

Matthew Kahut: That’s right. And the way I like to think about that, is, you can almost draw some concentric circles out from where the two lines cross. And you can sneak into the quadrant of high strength, high warmth area. The strength plus warmth quadrant. And this could be lots of people you know. You might say, “Hey, this person really gets things done, and I admire her.” And that might be somebody who’s in there for you. And then, you can think of somebody you’ve worked for, who was the best boss you ever had. And say, “Wow, that’s a person who’s really got it going on here. I admire that person.” And then, you can go for the history books. And you go for those people who you say, “Wow, great leader, who used all that capability on behalf of others.”

So, it’s not just people who have buildings in the town square, who make it into that upper quadrant there. Think about team captains, for instance, if you ever played sports. That person, ideally, is the person who was both great at their position, and also, they had the ability to inspire, lift up, really rally people together. And that’s the warmth side in that setting. So, that’s an interesting… I find that there’s room in each of these quadrants. It doesn’t mean you’re just kind of automatically the tippity top of each of them.

Brett McKay: Right. So, I imagine, whether you display strength or warmth, is very context dependent. So, it’s like some situations call for strength, and others, warmth. How do you figure out when you need to display strength, and when you need to display warmth?

Matthew Kahut: You’re spot on, that it is totally context dependent. And all of us are different in different settings, too. So, think about your work self and your family self, or your social self. And you’ll probably come across differently in different settings. You think about some jobs that are really competence driven, in the sense that you’re there, and it’s all business all the time, I don’t know. Air traffic controllers or something. Where, you really have to just be super hyper-focused, and the competence is the thing that you are there for. Then, it’s not so much about being, I don’t want to generalize about any given job. I don’t mean to say, air traffic controllers are warm people, by any means. But, certain such settings will obviously require you to focus on one or the other.

Go the other way, therapists. Therapists have to be great listeners. They have to start with that sense of drawing people out and being able to connect with them. So, certain settings tell you what they’re looking for. Beyond that, it really becomes a question of emotional intelligence, and asking yourself, “What do I need this person to understand for me? Do they need to understand that I can get this thing done? Or, do they need to understand that I see the world through their lens?” And I think you can ask these questions in a way that is not trying to manipulate people. It’s really from a question of shared understanding. To me, that’s what the real nugget of the book is. That, is that, it’s not about posturing, it’s not about putting on something. It’s about really asking yourself, “How can I help connect more deeply with this person? Do they need to know I can get this done? Or, do they need to know that I understand what matters to them?”

Brett McKay: Yeah. You talk about Machiavelli in the book. He said, in the print, “It’s better to be feared, than loved.” You’re saying, well, maybe sometimes, rarely. But, most of the time, you should probably look for being loved, and having that respect. Maybe not necessarily feared, but respected.

Matthew Kahut: Right. Well, okay. So, the Machiavelli thing, since we’re going there, if you read on, no one ever reads beyond that sentence. He says, “It would be best to be both, but it’s very difficult in one person.” And so, we’re going for the Michael Scott of the office answer, which is easy, both. And we’re saying, “Look, there are opportunities for most of us in everyday life. We’re not princes vying at the highest end of politics for skulduggery, and we’re not trying for the brass ring that Machiavelli was addressing in his book, The Prince. But, for most of us, day to day, I think that we have opportunities to show people both that we are capable, and that we care about the same thing as they do.

Brett McKay: And so, let’s talk about some of the things you dig into, and how we can display strength or warmth. And you start off talking about nonverbal cues that we give off. And the first one is our appearance.

Matthew Kahut: Sure.

Brett McKay: So, how does our appearance help determine whether we’re perceived as strong or warm? And by appearance, I mean, this could be, I mean, we can go clothing, we can go your body size, your body shape, whatever.

Matthew Kahut: Sure. Well, think about that for a second. One way to do this test for yourself, by the way, is, if you just are watching something on a screen, turn the mute button on, so there’s no sound, and just watch people. You can do this watching TV, or you can do it if… A great way to do this, if you actually are working on this for yourself, is, get some video of yourself out in the wild. If you’re in a meeting or something, or you have a presentation or a speech or something, get some video of it, and get a look at yourself with the sound off, and ask yourself, what do you see? And we see strength, typically, first through posture.

And you could be wearing a T-shirt, or you could be wearing a suit, and you’ll still see the strength in the way that someone expresses themselves through good posture. This is the freebie for me. For everyone, is just good posture. I mean, this is the low hanging fruit. And you’ll would be shocked how many times, John and Seth and I, are still telling people, “Hey, stand up, sit up.” Because, it’s one of those things that we know oftentimes, we’re just not aware of this in our day to day life. But, that is the nonverbal number one clue, that, we are, in some way, taking up our full height and our full width.

Now, you mentioned appearance and dress. And if we can dig into that a little bit too, if you want. It’s an interesting thing I’m not a fashion person, but I have just some thoughts about it. I’m curious, you had a specific question about that. Or, which one to go into more generally?

Brett McKay: Yeah, let’s go like, what type of clothing makes people appear competent and strong? And then, is there clothing types that make people feel, or perceived as warm?

Matthew Kahut: Well, I mean, obviously, some of the research on this, looks a little funny to me, just as somebody who’s read a lot of research. But, dark colors. There’s a reason people wear black in more solemn occasions and more somber things. When you think about the clothes that people in finance wear, they were blacks, blues and grays. And those things now, in our culture, we’re conditioned to think of those as the more sober and serious colors. And so, if you’re trying to affect a more professionally competent demeanor, those kind of choices can do that for you. Now, we’re in a shifting time too, and I spent a lot of times with tech firms. And, if you wear, God forbid, you wear a suit, you’ll be laughed at the office.

But, we have entire workforces, where people are wearing the equivalent of jeans and T-shirts to work. And so, then you’re making these choices, and you’re making them in ways that are through different gradations. Then, you saw, even 10 or 15 years ago on workplaces. And so, you have interesting choices around this stuff. That, I think it’s a shifting landscape, and I don’t have as hard and firm recommendations as I have for somebody who’s thinking about how they’re going to present themselves to a CEO of a Fortune 500 company. I think, like I said, it’s a moving target right now. The interesting question to me about it is, when something’s almost like uniform, and you’re trying to fit in, a little bit, that speaks to warmth, more than it does to strength.

Then, the question is, how do you also make sure that you’re showing people that you came to play, if you think of that as more of the capability side?

Brett McKay: Well, speaking of your world of politics, you see this sort of how people changed their clothes, where they’re displaying strength or warmth. At the debate, the men are wearing suits, power ties, whatever. Say, for Andrew Yang, he decided to go no tie, which caused an uproar. But then, when they go to the county fairs, they’ve got no coat on, they’ve got the top button unbuttoned, they’ve got their sleeves rolled up. They say, “Hey, I’m relatable.” So, there’s an example of that being played out.

Matthew Kahut: Absolutely. Mayor Pete’s an interesting example. He’s gotten some attention for the fact that he’s essentially wearing a uniform. He’s wearing the white shirt, the blue tie, every day. And it’s his brand now. He’s made that his brand, as much as Steve Jobs made the black mock turtleneck his brand. And it’s interesting, because, if you’re trying to stand out in a group of 20 people, then, doing something consistently like that, helps in that respect. And, in his case, is also a competence driven brand. He’s wearing the white shirt and the tie, that you could have seen anytime in the last 50 years essentially. And as a younger guy, as a guy who’s not just massive physically. He’s not 6’2″, 225 pounds or something. He’s asserting competence with that uniform.

Brett McKay: So, not only do our clothes can display warmth or strength. And again, as you said, it’s context dependent, you have to be very attentive to what’s going on in the group. But, just even like the appearance that we were born with, right? Like our head shape, our face shape, body shape, skin color. That can influence whether we’re perceived as competent or warm.

Matthew Kahut: Absolutely, yeah. All the stuff we’re born with. It’s funny, because, in some way, these things, it’s frustrating to talk about them on the one hand, because you have the hand you’re dealt, and there’s very little you can do about it. And then, what we try to focus on in the book is, the things you can turn the dials on. But you’re absolutely spot-on that these are the things that we show up with. And people do read signals into everything, from height, weight, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation. All those things do send strong or warm signals, and they quickly, rapidly descend into stereotype behavior too, or stereotype judgments rather, not the behaviors. The stereotype judgments of the people who are perceiving.

And look, all of us stereotype people, when we’re looking at them at first glance. And, if you think you’re not doing it, you’re probably fooling yourself, you are fooling yourself. Because, there has just been reams of research done on this. And it’s a challenging thing, and it raises all kinds of questions about how our brains work. But it’s a sorting mechanism, essentially, for us. And rightly or wrongly, it’s something that does, like you said, send the strength of warm signals.

Brett McKay: Well, do you know of one, for men, that, a common trait that you’re just born with, either you have it or you don’t, is height. I mean, the studies show that men who are taller, are perceived as more competent and powerful, and shorter men are not. So, if you’re a short guy, you might hear that’s like, “Well, I’m hose.” Not necessarily so, you highlight research and studies that show that, even a guy who’s not 6’5″, or 6’4″, or above six foot even, there’s things they can turn, dials they can can turn, where they can still be perceived as competent and strong by people.

Matthew Kahut: So, posture is the thing I mentioned earlier. And look, I’m 5’9″. So, for me, I sure do, I wish I were three inches taller, you bet. But, I’m not. And I’m relatively slender too. So, for me, standing up straight and taking up my full height with my shoulders, is part of what I just need to do, to make sure I don’t get lost in the shuffle. And doesn’t mean I walk around like a peacock, with my chest out. It just means, I want to be cognizant of that as somebody who’s a little smaller of stature than probably two thirds of the guys that I bump into, in a professional setting. So, there are things you can do around that. You also have choices around appearance too. And again, some people who want to make sure they don’t get lost in the shuffle, might make fashion choices to help with that as well.

So, there is a tall premium you mentioned it for sure. The funny thing about tall folks is, a lot of times, tall guys, because the world’s not built for them, they will slouch. And sometimes, they will throw away their natural advantage. That thing they were born with, that all the rest of us say, “Wow, I wish I had a couple extra inches.” Some of them will, in some way, undo that by slouching. And partly, it’s because doorways are too low for them. But, partly, it’s because they don’t want to hover over people. And they don’t want to make people uncomfortable. And when people are going into public facing settings, I always say, “Hey, own your height.” Because, you’ve got it, flaunt it.

Brett McKay: So, another nonverbal cue you talk about that can display both strength and warmth, depending on how you use it, is a smile. Which is interesting, because you think smile is just being warm. That’s how you show, like, “Hey, I like you. I’m okay, you can approach me.” So, let’s talk about, how can a smile display strength as well?

Matthew Kahut: Right. Well, we talked about this thing we call the steely smile. And the steely smile is that thing that you see that’s, first off, it comes paired with the good strength cues like posture. So, it’s your standing up, full height, full width, and your head is straight. And this is important. Because, one of the things that we don’t typically think about is, head angle also sends signals. If you’ve ever played with a baby or a puppy, and you’ve done this thing, where you cock your head back and forth, you can entertain babies for hours doing this, by putting your head off angle, and you smile at them, and they smile at you. And puppies will go… with you too. And that’s warm, when you have your head cocked off to the side. And that’s a great thing to be able to do when you’re trying to connect with somebody.

But, when you think about this stronger smile, it’s head straight up and down. It’s like a plumb line running straight down the center of you. And then, the smile is not that it’s your eyebrows or head. It’s not, “Hey guys, great to see you.” It’s, “Hey, how are you doing?” And it’s a smile on the bottom, but your gaze is relatively even at the top. It’s not the eyebrows up at half, the flag at half mast, so to speak. Now, that’s not to say that that’s not a good smile in other settings, but it’s the nice guy smile. And the nice guy smile says, “Hey, I’m not a threat.” The stronger smile we’re talking about here, where your posture is solid, and your gaze is relatively level, it’s still a smile. Your eyes are still crinkled at the corners, but you’re not as eager as the eyebrows up smile, if you will.

Brett McKay: Another aspect of something in our face that displays strength or warmth are our eyes. What role does eye contact play in conveying strength or warmth?

Matthew Kahut: Eye contact is so interesting, and I just want to be really clear at the outset. Eye contact is the most culturally specific cue that is hard to generalize about. So, eye contact in American settings… I hate to generalize about it in American settings, because we’re a huge country of a diverse population. But, the norms you see, let’s say, in American professional settings, are that, a lot of eye contact is expected. Especially, if you’re listening to someone, you’re expected to be looking them in the eye. And the fact that we’re comfortable with eye contact, where somebody says we’re confident. And it’s also a way we connect with people. So, eye contact is really about strength and warmth.

One of the things we mentioned the book, is that, two words that speak to this, have a shared root. Think about intimacy and intimidation. Two boxers at the way in, they’re staring each other down, that’s the intimidation factor. It’s all eye contact, and whoever blinks first, loses. And an intimacy, obviously, in love, we’re making eye contact with people. And so, it’s interesting how eye contact is really required of us for both. And if we’re uncomfortable with eye contact, or we’re avoidant with it, then, it can raise questions about trustworthiness, or our comfort with something, or our confidence. It can raise a whole host of questions, depending on what the context is.

Brett McKay: Yeah. You’ve even said, in America, it can be very context dependent, even like in the situation. So, in some cases, someone not giving eye contact to somebody, would be like a strength display, right? It’s like, “You’re just not even worth looking at, I’m going to look away from you.” Right?

Matthew Kahut: Right. Yeah, and that’s so funny. Because, in another setting, not looking someone in the eye, could be, you’re avoiding them because you’re scared of them. So, you’re spot-on, it’s at 100% context driven.

Brett McKay: Or, you can stare someone down. And that’s like a display of strength. And then, sometimes, you look someone in the eye because you’re supposed to show respect. So, it’s like a subservient thing. So, yeah, it’s all context dependent. So, you’ve got to have that, I guess, develop that emotional intelligence to figure out what’s the best thing to do in whatever situation.

Matthew Kahut: That’s right. One last thing I’d say about this, is, if somebody’s not giving you the eye contact you’re expecting from them, this is especially true in a work setting, ask yourself, could there be a cultural thing in play here? Or, could it be that this person’s uncomfortable in some way. And I would just suggest that people be generous about that a little bit. A lot of the stuff we’re talking about around body language and nonverbal communication, it can almost become this thing of a checklist in people’s minds, “Oh, they’re not looking at me, therefore, it means X.” And I would suggest being a little more generous, especially around eye contact. Because, you just don’t know how people were raised. And there are so many different expectations culturally, even among people who are raised in different parts of the country, that I really hesitate to generalize too much about it, and I encourage people to try to understand that people may have a different norm or expectation, depending on where they’re from and what was normal where they grew up.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I think that’s a good point about not obsessing too much about this stuff, and making it a checklist thing. Because, what ends up happening is, you’re going through your head, it’s going to make whatever encounter you have, super awkward, right? Or, could make it awkward. Because you’re just thinking, “Okay, am I being strong? Am I being warm?” So, you’re probably not looking strong, because you’re looking like, going through the thing through your head. And you’re also not looking warm, because you’re being incredibly awkward. Because you’re trying to figure out, “All of my boxes checked.”

Matthew Kahut: Totally, yeah. It’s funny, Bruce Springsteen said something, about year or two ago, that completely caught my ear about this. He said, “The weirdest and worst place you can be, when you go on stage, is if you suddenly realize, “Hey, I’m on stage now.” Because, you’re not there, you’re just thinking about the fact that you’re there.” And the same is true around all this. And here’s where this gets tricky is, how you operationalize the insights in the book around posture, or gesture, or eye contact, or anything like that, and it’s really, a process of making this stuff second nature. And so, there is a learning curve. And at some point during that learning curve, it does feel self-conscious. And the idea is to get this beyond self-conscious to the point where it becomes unconscious.

Because, our nonverbal behavior is largely, utterly unconscious to us. We’re really not aware of what we’re doing. And if you’re thinking, “Where are my hands?” Something like that. Then, you’re distracting from making a really good connection with somebody. And so, going from that conscious incompetence to the unconscious competence, as they call it, that continuum, it does take a little bit of practice, and there is a process where this stuff leaves your conscious mind, and you want to get there as soon as you can. And that’s why, one of the things we do when we’re working with speakers, is getting them practicing, practicing, practicing, watching themselves on tape, and then forgetting about it, so that these things become second nature, and you’re not thinking, “Oh, my gosh, I’ve got my head off axis again,” or whatever.

Brett McKay: So, you’re talking about nonverbal cues, how can our words display strength or warmth?

Matthew Kahut: Well, let’s start on the strength side. A lot of strength is about being very clear, being very concise, and knowing what you’re talking about. Thinking about it as expert. Clear, concise, and expert. And people who tend to talk in bullet points, that’s what that’s about. An extreme of this might be, if you think about military communication, where it’s very critical that you communicate the bare facts really quickly, and no one is unclear about it. Or, think about communication in operating rooms, where people have to be very specific about what they say, that’s really strength-based communication in a lot of ways. And there are lots of different kinds of settings where you can think about that, where the words are very carefully choreographed and mapped. And anything that’s extraneous, is out, because it’s not helping with the competence.

The thing that I find as much more interesting in some way, is that, the warmth side is where there’s often a lot of low hanging fruit. And when you think about what warmth in words means, it essentially means, you’re connecting with people. You’re showing them you care about the things they care about. And that, I find, they tend to not necessarily have the vocabulary for that, or think about ways that you can demonstrate that.

Brett McKay: I mean, what does that look like, for the warmth side?

Matthew Kahut: Well, we talked about this idea of showing people that you understand their concerns, their interests and their emotions. And the way you do that, there are a couple different ways. One of the easiest ways, the shortcut to do this, essentially, is to tell them a story that shows them, rather than trying to tell them. Rather than saying, “Oh, yeah, I get where you’re coming from.” You use an anecdote, or some sort of a story that essentially demonstrates exactly that. Because, we’re all wired to take in the story, we love stories, just as human animals. And if you can use story language to show people that you felt the same way they felt, you’ve experienced something that’s similar to what they’ve experienced. All of a sudden, they feel that sense of connection, you didn’t have to do anything to make that point.

There are a couple other things too. So, one is using the same language they use. I know that sounds really obvious. I don’t mean, you’re speaking English, they’re speaking English. I mean, using the same kind of vocabulary they use. Sometimes, people who have specialized lingo, for instance, speak that specialized lingo around people who don’t speak it, and then, the people they’re meeting, are lost, and they don’t know what the heck they’re talking about. So, that creates a barrier to that warmth, to that sense of connection. And being actually a great listener and asker of questions. I don’t mean an interrogator, but somebody who really takes an interest in other people, that’s where warmth starts for me. Is by saying to somebody, “Hey, it’s great to meet you.”

And then, getting into what’s interesting to them. And just being the person who’s able to ask them a simple question and unlock things, and say, “Huh, that sounds really interesting, tell me more about that.” If you are good at that, you’re good at warmth. Now, the last thing along this line, is validating people’s concerns, their interests. Especially, their emotions. Where, you’re dealing with somebody, and they say, “Matt, I’m really frustrated that you did blankety-blankety-blank.” If you can validate that frustration, that goes a long way toward demonstrating this warmth. And especially around emotions, everybody’s emotions are true on their face. You may not agree with somebody about the substance of something, but you can’t argue with people’s emotions.

And if you can validate their emotions, when they say, “Look, I’m frustrated.” And you say, “Look, I hear you, and I’m sorry that this is frustrating. I know what you mean.” If you can do that from a place of legitimate agreement, or some sort of affirmation. Well, it’s not window dressing, you have to feel it, that’s the trick here. Is, it has to be genuine. But, if you can validate like that, that’s the warmth with words.

Brett McKay: So, yeah, you gave a great example of showing that you understand, instead of telling you understand. You gave the example of Robert Kennedy, when he was giving a speech, he was in Minneapolis, it was in front of a lot of… I guess, the audience is African American. And he got the news that Martin Luther King was assassinated, and he had to be the one to break the news. And he did it in a way where, he showed people that he understood the anger and pain they felt.

Matthew Kahut: Right. That’s right. That, this is a really great historical example. Where, I mean, you think about the anger in that community, and the sense of outrage that Martin Luther King has been assassinated. You’re in an African American community, you are a white man who’s standing there to deliver this news. And you know that this could provoke any kind of reaction. It could provoke violence, it could provoke any kind of thing from an audience that’s going to feel so devastated by this. And he talked about the sense that he had experienced loss too, he had lost a brother too. And everyone in that audience knew what he meant, because they knew about his own brother being assassinated. And he didn’t, in any way, it was nothing condescending in the way he did this, he just was pitch perfect in the way that he expressed that sense of anguish about what people were feeling, and was able to connect himself to it, in a way that was genuine, because of his own shared past, that people were already familiar with.

We call this move, getting in the circle with the audience you’re with. And if you can do that, if you can show people who are already in one place that you have felt the same way, or you do feel the same way, or you have some experience that legitimately connects to the way they are feeling, or the thing they’re experiencing, that’s it. That’s really what warmth comes down to.

Brett McKay: So, let’s talk about this display of strength and warmth in different situations that all of us will encounter. One example you gave was a job interview. And so, that’s one, you have to show both. Because, the goal is you want to show you’re competent. But, also, two, you’re trying to show, “Hey, you would really want to work with me, I’d get along with you.” So, how do you do both in that one, maybe 20 minute interview.

Matthew Kahut: You’re spot-on that you are going to be showing both in these settings. Here’s my thought about that, is, the resume got you in the door on your competence. The resume doesn’t typically do warmth, it’s a strength display. And then, the questions, as they come, are asking you to do a little bit of both. To me, the, “Tell me about yourself,” question, which is often the first one that comes in, is asking you to do, essentially, the quick version of, “So, here’s who I am as a person. And here’s what kind of person I am, here’s what kind of professional I am.” And you’re doing a little bit of the competence by being relatively succinct about it and knowing your story that you can give somebody in that fairly quick bite there.

I think, part of what you’re trying to remind people, like you said, is that, you’re going to be a good team player. You’re going to be somebody people are going to want to come to work with. So that, as you’re thinking about showing people examples of what you’ve accomplished in the past, it’s not about you, it’s not the me show, it’s the me, succeeding with others, helping others succeed, being the person who was able to lead, or to be the driver of that collaboration. Because, honestly, none of us get anything done alone at work, it all happens in a team setting. And reminding people that you know how to work effectively with others, to lead others effectively, whatever, however you want to characterize that, that’s what a lot of the warmth is going to come across, as far as the content of what you say.

Then, the way you say it, of course, is, it’s not rambling, it’s not just the me show. It’s showing the person that you’re listening to their questions, and giving them appropriate signals non-verbally, that you understood what they want to hear. It’s a whole combination of those things that does the warmth there too.

Brett McKay: So, another thing that people, well, all of us probably have to do at some point in our life is, either give a speech, or a presentation. And I thought, in the book, you guys made a really interesting point that, public speaking is a lot trickier now than, say, 100 years ago. Why is that? What’s changed?

Matthew Kahut: Well, it’s interesting because we live in the age of Ted. And there are literally hundreds of thousands of people who have met this level of speaking that they need to do, where, they’re putting on these 10 to 15 minute talks, they’ve got them memorized. And, nowadays, we are really prioritizing conversation over oration. And what I mean by that is, a Ted talk is supposed to be intimate. And part of the intimacy is where you’re wearing a microphone. So, you can use your conversational voice. You’re not orating, so that the people in the back of the room can hear you. You’re not projecting your voice in some way, that people had to, before amplification. And, you’re supposed to give people some of yourself, as well as know stuff.

And, I think it’s tricky, because, first off, the bar’s high because of the TED effect. But, it’s also just that, the time where you have to figure out, how can you bring enough of yourself, so people get that sense that you’re showing them your true, or authentic person? And, how can you demonstrate that sense of competence or expertise that people want to take from you, something for them to hear. Why were they listening to you in the first place? Was it something interesting about your background? Do you know something? And it’s making sure you balance those things, that’s, in some way, fundamentally different than it used to be. Where, it was more about speakers, speaks, audiences, listen. Now there’s a more conversational dynamic to it.

And what was more formal speech, now it just sounds stiff and wouldn’t. So, it has to have that conversational tone. And yet, you also have to hit that mark for competence.

Brett McKay: So, how do you display that intimacy and warmth, when you’re in front of a large audience? You can have a more conversational tone, but, are there other nonverbal cues you can do?

Matthew Kahut: Absolutely. And a good speech will take you on a journey, and it’ll do a bunch of these things. And sometimes, there will be a moment where you’re really just hitting the marks on what you know. But then, sometimes, there will be there, a change of direction, or a pause, or a break. And someone will tell a more personal story. Maybe their voice will come down a little bit, and say, “Look, this is really hard.” Something that you’re listening and you’re connecting to them as a person, and then, they bring you back up. And so, it’s thinking about hitting multiple notes in a talk. It’s not all at one level the whole time, it’s making sure that there are different beats in it, where you’re connecting with what people already know. And then, taking them into unfamiliar territory, where they haven’t been there before, and giving them enough variety.

It’s like a symphony, where you’ve got to have enough different movements to it, that, it keeps people engaged the whole time, but also, takes them into unfamiliar turf at some point.

Brett McKay: So, what do we do with our hands? That’s the question everyone is asking now. What do I do with my hands, when I’m not there?

Matthew Kahut: Right. This is the one thing, when we work with people in person, that they remember more than anything. Because, everybody’s obsessed with this question. Now, look, let’s just acknowledge culturally that there are differences around gesture around the world. So, let’s put that on the table. Within the United States, at least, one way to think about this is, a lot of times, the gesture that’s seen as strong, and almost as a cliché, is the karate chop. It’s the kind of straight down, your hand’s almost like a blade. It goes straight down and says, “Look, here’s the thing,” and it’s very insistent. And if you’re twice as strong, it’s the double karate chop. The right hand and the left hand.

And you can almost look like a Ginsu knife salesman on infomercial, at two in the morning, saying, “Buy now,” with the hands like that. It’s kind of a joke. And then, that’s where we think about it as an extreme of strength. On the other extreme of warmth, think about if you’re welcoming your relatives, who have come great distances to see you. And you open your arms to them at the airport. And so, warmth is really opening ourselves to people. Strength is almost drawing that barrier. And if you think about the balance between these things, between this blade that’s cutting the air in front of you, and arms wide open, it’s almost like, imagine you had a basketball in your hands, and you had it somewhere between your hips and waist.

Yeah, go ahead and do it right now. Imagine you’re-

Brett McKay: I’m doing it right now. Yeah. Definitely, an imaginary ball here.

Matthew Kahut: The imaginary ball is actually a great tip, if you’re the kind of person who’s not sure what your hands should be doing when you’re gesturing. And, depending on the point you’re making, your ball can get bigger or smaller. So, if you’re making a little bit bigger point now, now make your ball a beach ball. Now, if you’re ever going to do one of these TEDx talks or something like that, that biggest point your life, that big takeaway, is that thing at the gym, that Pilaties ball, that giant thing. And now, you’ve got the ball out, it’s maybe beyond your shoulders on either side. Now, you can shrink the ball back down. Now, maybe in your left hand, there’s just a baseball there for a second. So, move that baseball out to the left side. Maybe shift hands, put the baseball on the right hand side. Sometimes you can pass it almost like a basketball. And the ball is a helpful corrective, if you’re the kind of person who flops around a little bit with your hands.

I don’t mean to say, “Hey, just do this ball thing all the time.” That would be a misconstruing of what I’m saying here. But, if you’re a person who you’ve seen yourself on video, and your hands tend to flail all around, and they’re just doing things like the illegal motion sign that you see your referees do in football. Or, something that is not consistent with what you’re saying, the ball can be a nice thing. Because, it does a little bit of strength, and a little bit of warmth. It’s open, but it also has a little bit of control or poise to it.

Brett McKay: So, let’s talk about a crisis time. Let’s say, at work, you’re a leader, and that something’s happened, right? It’s all hands on deck. I imagine, again, you’re wanting to display strength, to show that, “Hey, we’ve got a plan.” But, you’re also wanting to display warmth, because people are probably feeling anxious or whatever. So, what does that look like?

Matthew Kahut: It’s so specifically context driven, that it’s hard to generalize. Sometimes, you have to be the person that says, “All right, let’s do this.” And that can be the perfect answer. And that’s the thing that sets people’s minds at ease, on that setting. Depending on another instance, it might be the person that says, “Look, this is really tough.” And they do the warmth move first. And then, they say, “Because this is urgent, I’ve got to go do this.” It can be a quick pivot there, depending on the setting. So, it’s hard to know what the setting, who the protagonists and what the specifics of the challenge are. But, if there’s a question of people needing a little bit of a morale boost, maybe that’s where the warmth moment comes. If it’s really about, “Which way do we get out of the jungle here.” Being the person who says, “Let’s go that way.”

That can be the place where you say, “Okay, we need just the strength, the competence answer now. And somebody who sounds like they know which way to go.

Brett McKay: So, you’re going get the balance, strength, and warmth.

Matthew Kahut: Right.

Brett McKay: Sometimes, show strength. Sometimes, you’ve got to show the warmth. Well, Matt, this has been a great conversation, where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Matthew Kahut: Well, the book is out there on Amazon and all those places. And we have a bunch of resources on the KMB Communications’ website about this. And I’ve written a few things on medium over the years, that people can find as well, if they just search on my name. It’s been a real pleasure to talk with you about this. It’s been fun seeing this stuff work out in the wild for several years at this point, and it’s fun to talk through it with you.

Brett McKay: Well, Matt Kohut, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Matthew Kahut: Thanks for having me.

Brett McKay: My guest is Matthew Kohut, he’s the co-author of the book, Compelling People. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. Check out our show notes at aom.is/compellingpeople, where you can find links to our resources, where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of AOM podcast. Check it at our website at artofmanliness.com, where you can find our podcast archives. There’s over 500 episodes there, as well as thousands of articles we’ve written over the years, on things like charisma and social skills. Stuff we talked about in the podcast today. And if you’d like to enjoy add free episodes of The Art of Manliness podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, use code, manliness, to sign up for a free month trial Stitcher Premium. Once you sign up, download the Stitcher app in Android or iOS, and start enjoying the new episodes of Art of Manliness podcast, ad free.

And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate it if you take one minute to give us review on iTunes or Stitcher, it helps that a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member, who you think would get something out of it. Shoot them a text or something. As always, thank you for the continued support, until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you not only listen to the AOM podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.