From boyhood all the way through my college years I loved playing video games – many a night you could find me mashing the buttons on my controller as I worked my way through the levels of Super Mario Brothers and killed bad dudes in GoldenEye.

These days, as a husband and father of two young kids, I don’t have the time nor desire to plant my keister in front of the latest console. And yet there’s an aspect of video games that’s still a part of my day-to-day life. While I’m no longer playing a video game, I’m living one…in the way I parent my children.

Why You Should Parent Like a Video Game

Our oldest kid, Gus, will be four in October. One of the trickiest parts of parenting is figuring out how to get your kid to do stuff they’re supposed to do and stop doing stuff that’s annoying, i.e. temper tantrums, talking back, writing on the walls, etc. No one tells you that parenting is basically one giant psychological experiment in human motivation. Before Gus came along, Kate and I had only a vague idea of how we were going to handle our kids’ misbehavior, but it wasn’t very fleshed out, or, more importantly, field-tested (everybody knows exactly how to be an awesome parent…before they have kids!).

Everyone loves to give you advice about what you should and shouldn’t do when it comes to parenting, and there are umpteen thousand books and blogs out there that this or that friend will rave about. But really, the principles of good parenting are pretty tried and true and generally agreed upon. The real trick is remembering to implement them when you’re about ready to load your toddler into a cannon and shoot ‘em to the moon.

On that front, there is one metaphor that has helped Kate and I tremendously in adopting positive practices: parent like a video game. I picked up this analogy from psychologist Howard Glasser, who argues that the principles that govern the world of video games are also highly effective in getting your kids to behave.

Let’s take a look at what those principles are and how to implement them into your parenting style:

Establish Clear Rules

When you’re playing a video game, you know that button A makes you punch, that touching a bad guy will kill you, and that you need a certain amount of XP before you can level up. Knowing the rules helps you operate confidently within the game’s landscape.

In the same way, make sure your kids know what the rules are in your family. A study done in 1967 by Stanley Coopersmith showed that parents who gave their kids the most rules and limits had children with the highest self-esteem, while those who gave the most freedom had kids with the lowest self-esteem. Kids want limits, and they’re essential to healthy progress.

Keep your rules clear and simple, just like in a video game: input A gets you output B. Every. Single. Time. Giving your child consistent limits, rewards, and discipline is one key in helping them develop an “internal locus of control.†People with an internal locus of control believe that by doing A, they can get B — they see a correlation between action and consequences versus believing in blind luck or that the world is out to get them. Show your kids that good behavior leads to reward, bad behavior leads to punishment.

Promise a reward for an accomplishment, and give it to your child if and only if they attain it. Set a rule and punishment, and if the rule is broken, follow through on the exact punishment promised. Consistent parenting ingrains these kinds of connections in your child’s mind, and bolsters their confidence and resilience.

When they do violate a rule, let them know that they did and begin the “resetâ€:

Issue Short, Consistent “Resets†for Bad Behavior

In Super Mario Bros., if Mario touches a Goomba, he dies and has to start back from the beginning. There are no warnings or counting to three or bargaining with the Goomba about whether or not Mario dies. Mario doesn’t get lectured about how he shouldn’t touch unsuspecting Goombas, nor is he asked why he wasn’t paying attention. Ultimately, Mario touched the Goomba, so he has to go back to the beginning. That’s it – that’s the rule.

Moreover, Goombas stay dispassionate when dispensing their punishment. Sure, they always look grumpy (you’d be grumpy too if you were a mushroom) but they don’t get any grumpier when Mario dies. They just keep shuffling back and forth, pretty much like nothing happened.

The consequence for touching a Goomba is also short-lived. Mario flies up into the air and that trademark “Mario Dies†music plays. But then you’re immediately playing again. You’re not sent to some dungeon level where you have to watch Mario just stand in a prison cell for 10 minutes before you can jump back into the fray.

The consequences for your kid’s misbehavior should be similarly consistent, dispassionate, and swift. Glasser argues that when we engage in heated lecturing and angry cajoling after our kids mess up, we’re just “rewarding†them with our energy and attention — two things all children want from their parents. The form that attention takes isn’t as important to them as the fact that they’re getting it — period. As Glasser shrewdly observes, “No one would purposely give a child a hundred dollars for breaking a rule, but we inadvertently do it all the time by way of giving children the ‘gift of us’ as we are doling out the consequence.â€

Instead, when your kids break a rule, the consequence should kick in immediately without a bunch of preliminary back and forth and emotional hullabaloo. Don’t give them a warning and don’t negotiate with them. Just issue the consequence, be it a time-out or taking away screen time or adding a chore to their routine. Glasser argues that any consequence that temporarily takes away the kid’s options and deprives them of your attention can be effective.

When you deliver the consequence, do it dispassionately. Don’t get angry or raise your voice and start lecturing or ask why they’d do such a thing. And never criticize their character (“You’re so naughty!â€), but just their behavior (“We don’t throw blocks in this house.â€). Making them feel as though their character is inherently flawed just induces passivity and hopelessness. Bad behavior, on the other hand, is temporary and something they can work to overcome. As neutrally and unemotionally as possible, simply say something like, “Uh oh, you’re throwing a tantrum. You broke a rule. Go to your room to calm down and stay there until I get you.â€

In addition to staying completely calm as you issue a consequence, remember to keep the punishments as consistent as possible in both their timing and severity. Remember, input A gets them output B. Every time they throw a block, you calmly send them to time-out. Don’t let your mood dictate the punishment, so that when you’re tired and don’t want to deal with it you just let the infraction slide, and when you’re irritated, you totally flip out on them. Every time they break a certain rule, they get the same dispassionate tone of response, and the same punishment. See? This is what happens when you touch a Goomba.

It’s also important to make the time-out, or “reset†short, just like in video games. You don’t want to sequester your kid in their room for twenty minutes only to have them throwing books from their shelves and rolling around on the ground screaming like a banshee the entire time. The purpose of the reset is to get kids to stop whatever inappropriate behavior they’re doing and then get them back into “game play†as soon as possible so that they can get positive reinforcement for behaving well. Time-outs don’t work unless kids have rich time-ins, which brings us to…

Create Rich and Rewarding Game Play

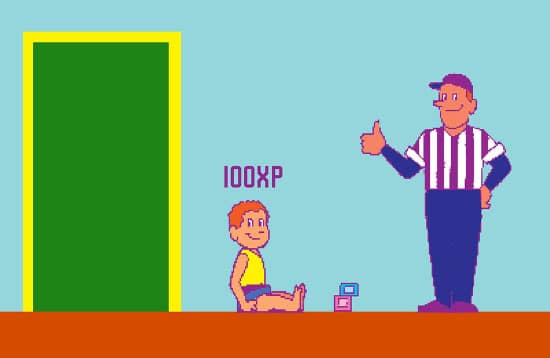

In video games, it doesn’t matter how much you die and get sent back to the beginning, you still want to keep playing because the game play is so stinking fun and rewarding. You’re constantly getting feedback and rewards for accomplishing certain tasks. Stomp a Goomba, and you get 100 points; kill a bad guy in Final Fantasy, earn XP; beat a Big Boss in Zelda, get a piece of the Triforce. The video game is ready and waiting to reward you with coins, XP, or new weapons as soon as you do something that warrants them.

Whenever we experience a reward in a video game, our brain gets hit with a bit of dopamine which 1) makes us feel good and 2) re-wires our brain to motivate us to keep on doing what we’re doing. The way video games stimulate our dopamine production is part of what makes them so seemingly addicting. Resets in video games due to dying or not completing a level in time only make you more driven to get back into the game and get some more hits of that feel-good dopamine.

Thus with kids, Glasser argues that the key to making time-outs work is that you have to make “time-in†or “game play†rich and rewarding by giving your kids positive energy and attention for the good stuff they’re doing (or the bad stuff they’re not doing). “If the child perceives there is nothing worth missing out on then what is the motivation for wanting to stay in the game?†he asks.

Creating rich and rewarding game play for our tykes can be pretty hard. Unlike video games that are programmed to reward you anytime you do a certain task, us human dads lack the omnipresence to dole out praise for every good thing our kiddo does.

The other thing that makes creating rich and rewarding game play difficult is that the simple act of showing appreciation is hard, especially when you’re trying to praise your kids for bad behavior they’ve managed to abstain from. Our minds are evolved with a negativity bias so that “bad things†sound alarms in our brains while “good things†hardly register. So it takes intentional work to remember to point out and give praise to your toddler when he isn’t throwing a tantrum in the face of a potentially frustrating situation.

But that effort pays off. Glasser and other researchers point out that positive feedback is more effective than negative feedback in teaching kids appropriate behavior. So as much as you can, aim to “catch†your kids doing something good. Point out and praise even the most mundane actions. If your kid picks up her toys without asking, say something like, “Jill, that was great how you picked up your toys. It showed me how considerate you are and how much of a good helper you are.â€

Just as importantly, point out and show appreciation when your tyke isn’t doing something he shouldn’t be doing. For example, if your kid usually throws a temper tantrum when you tell him it’s time to go to bed, but this time he heads to his room without a peep, say, “Brian, I appreciate how you started getting ready for bed as soon as I told you to. Way to stay calm, buddy.†Ding! Your kid just stomped a Goomba.

If he’s sitting at church and keeping himself occupied quietly, say, “Sam, good job staying quiet and calm during church. I know it can be hard to do that sometimes.†BAM! Your tyke just earned 1000XP and is on his way to leveling up to a well-adjusted adult.

I know there’s a current in our culture that says kids are over-praised and that this coddling turns them into entitled brats. There’s some truth to that, but here’s the key difference: With this parenting method, you’re not rewarding them for nothing, or just for being. You praise them for good, small, tangible things they actually do. It doesn’t turn them into spoiled turds; it creates a neural pathway where they keep wanting to do the right things again and again.

Stay in the Moment

Video games don’t hold grudges about past slip-ups nor do they sit around anticipating that you’ll mess up in the future. Video games are present in the moment; every game is a fresh start in which the pitfalls to be avoided are exactly the same, and the player has exactly the same chance to earn rewards as he always does.

Don’t hold a tantrum that your kid threw yesterday over his head today nor treat your kid like he’s already committed a peccadillo even when he hasn’t. Just keep doling out dispassionate resets and consistent rewards.

Conclusion

Clear rules and consistent punishments bolster children’s resiliency because they know exactly what to expect. Doing A will always get them B — for better and worse. They know they can choose their behavior, but they can’t choose the invariable consequences. And positive reinforcement motivates them to more often choose good behavior over bad. This isn’t groundbreaking advice, but the video game analogy has honestly proven amazingly effective in helping us both remember to implement these tried and true principles on a day-to-day basis. It’s actually become somewhat of a game for us, in seeing just how calm and composed we can remain while issuing consequences, and how often we can catch Gus doing something good.

So far this parenting methodology seems to be working great. That’s not to say that Gus is the paragon of a well-behaved child. He has his moments, but for the most part he’s a really good kiddo. Our times hanging out are largely calm, enjoyable, and a lot of fun. Of course it’s hubris to think that just because your kid is doing well now, he’ll continue to stay on the right path as he grows up. No parent knows what will happen over time and I can’t make any claims for this method’s long-term efficacy. I can just say that for now this approach has been very effective for him, and it’s given us an accessible, helpful framework for guiding our parenting decisions, instead of going at it willy nilly.

So, when it comes to parenting, rather than harnessing your inner Dr. Spock, consider tapping into your inner Dr. Mario. Now if there was only a Konami Code for potty training….