When Theodore Roosevelt assumed the presidency in 1901, he became, at 42 years old, the youngest president in the country’s history, and his children with wife Edith were similarly youthful in age. Theodore III (14), Kermit (12), Ethel (10), Archibald (7), and Quentin (4), along with seventeen-year-old Alice from TR’s first marriage, brought an unprecedented level of enthusiastic, early-years energy to the White House.

Though the responsibilities of his office were great, Roosevelt always tried to carve out time for his children, and when he was away on travels, or they were away at school, he would write each of them weekly letters. His children cherished and preserved these missives, and a collection of their father’s favorites was published in 1919; TR said of Theodore Roosevelt’s Letters to His Children: “I would rather have this book published than anything that has ever been written about me.”

While Roosevelt’s larger-than-life accomplishments and private character can sometimes make him seem remote and inaccessible, his letters to his children reveal his personable, playful, paternal side, and his deep love for his family. He wrote warmly about the household’s horses and pets, his roughhousing escapades with the younger children, and, befitting his once-considered career as a natural historian and love of the outdoors, the flora and fauna of his environments at home and aboard (“I think I get more fond of flowers every year,” he enthused).

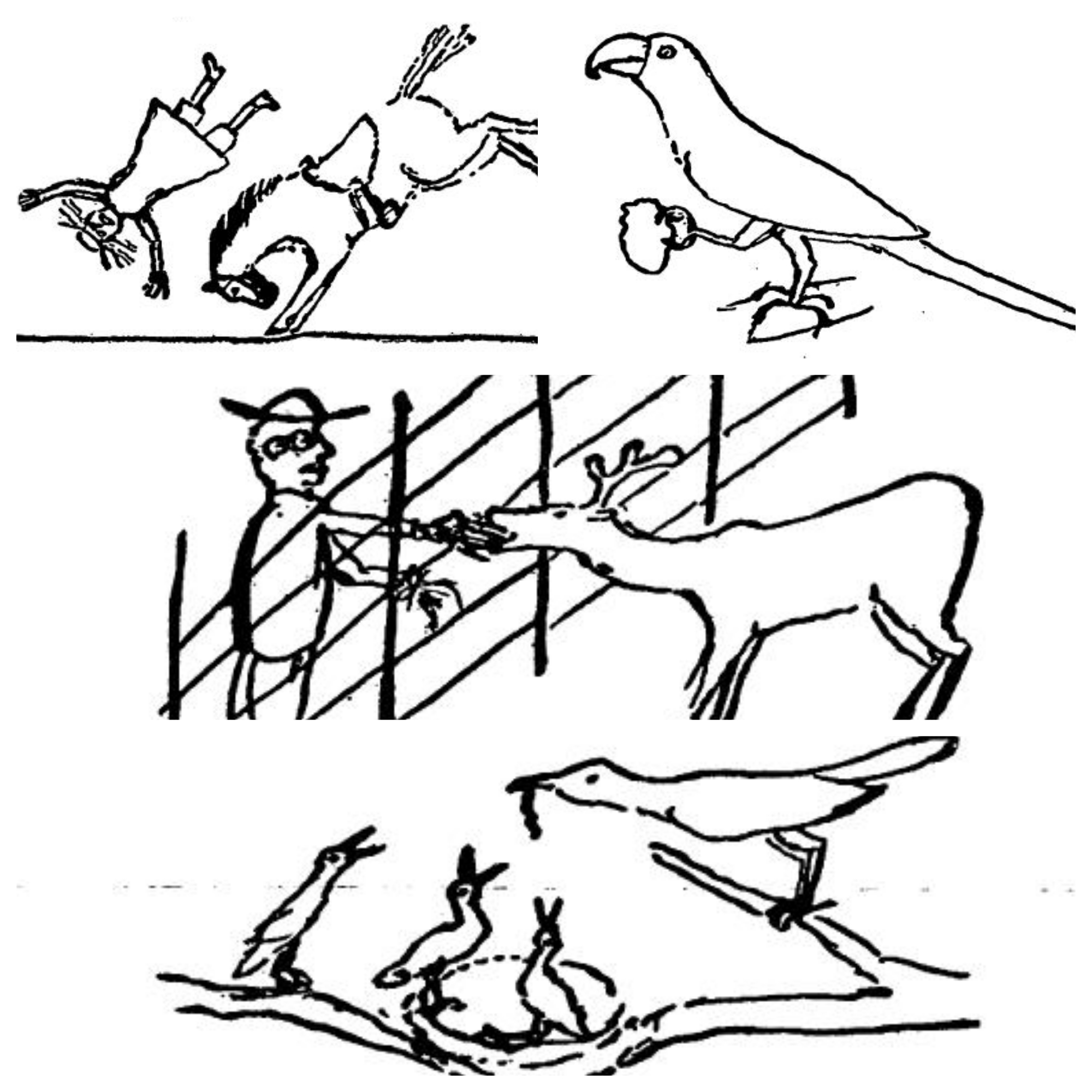

Some of the drawings Teddy included with his letters to his children.

When his children were young, he often included funny pictures in his letters; as they grew older, he increasingly talked of meatier matters. As the introduction to the book notes, “The playmate of childhood became the sympathetic and keenly interested companion in all athletic contests, in the reading of books and the consideration of authors, and in the discussion of politics and public affairs.”

While he only rarely offers his children direct advice, and doesn’t wax poetic on what it means to be a dad, the letters create an indirect impact that’s even more salient; they impart subtle-but-potent inspiration as to what fatherhood should look and feel like.

While the whole delightful volume is worth a read, below are a selection of some of our favorite letters (some condensed) from TR to his children (as well as a few to relatives/friends about his children).

ARCHIE AND QUENTIN

Oyster Bay, May 7, 1901

BLESSED TED:

Recently I have gone in to play with Archie and Quentin after they have gone to bed, and they have grown to expect me, jumping up, very soft and warm in their tommies, expecting me to roll them over on the bed and tickle and “grabble” in them. However, it has proved rather too exciting, and an edict has gone forth that hereafter I must play bear with them before supper, and give up the play when they have gone to bed.

Today was Archie’s birthday, and Quentin resented Archie’s having presents while he (Quentin) had none. With the appalling frankness of three years old, he remarked with great sincerity that “it made him miserable,” and when taken to task for his lack of altruistic spirit he expressed an obviously perfunctory repentance and said: “Well, boys must lend boys things, at any rate!â€

WHITE HOUSE PETS

White House, June 9, 1902

MY DEAR MR. HARRIS:

(To Joel Chandler Harris)

Last night Mrs. Roosevelt and I were sitting out on the porch at the back of the White House, and were talking of you and wishing you could be sitting there with us. It is delightful at all times, but I think especially so after dark. The monument stands up distinct but not quite earthly in the night, and at this season the air is sweet with the jasmine and honeysuckle.

All of the younger children are at present absorbed in various pets, perhaps the foremost of which is a puppy of the most orthodox puppy type. Then there is Jack, the terrier, and Sailor Boy, the Chesapeake Bay dog; and Eli, the most gorgeous macaw, with a bill that I think could bite through boiler plate, who crawls all over Ted, and whom I view with dark suspicion; and Jonathan, the piebald rat, of most friendly and affectionate nature, who also crawls all over everybody; and the flying squirrel, and two kangaroo rats; not to speak of Archie’s pony, Algonquin, who is the most absolute pet of them all.

WESTERN CUSTOMS AND SCENERY

Del Monte, Cal., May 10, 1903

DARLING ETHEL:

I have thought it very good of you to write me so much. Of course I am feeling rather fagged, and the next four days, which will include San Francisco, will be tiresome; but I am very well. This is a beautiful hotel in which we are spending Sunday, with gardens and a long seventeen-mile drive beside the beach and the rocks and among the pines and cypresses. I went on horseback. My horse was a little beauty, spirited, swift, surefooted and enduring. We had some splendid gallops. By the way, tell mother that everywhere out here, from the Mississippi to the Pacific, I have seen most of the girls riding astride, and most of the grown-up women. I must say I think it very much better for the horses’ backs. I think by the time that you are an old lady the side-saddle will almost have vanished—I am sure I hope so.

It was very interesting going through New Mexico and seeing the strange old civilization of the desert, and next day the Grand Canyon of Arizona, wonderful and beautiful beyond description. I could have sat and looked at it for days. It is a tremendous chasm, a mile deep and several miles wide, the cliffs carved into battlements, amphitheaters, towers and pinnacles, and the coloring wonderful, red and yellow and gray and green. Then we went through the desert, passed across the Sierras and came into this semi-tropical country of southern California, with palms and orange groves and olive orchards and immense quantities of flowers.

TREASURES FOR THE CHILDREN

Del Monte, Cal., May 10, 1903

BLESSED KERMIT:

The last weeks’ travel I have really enjoyed. Last Sunday and today (Sunday) and also on Wednesday at the Grand Canyon I had long rides, and the country has been strange and beautiful. I have collected a variety of treasures, which I shall have to try to divide up equally among you children. One treasure, by the way, is a very small badger, which I named Josiah, and he is now called Josh for short. He is very cunning and I hold him in my arms and pet him. I hope he will grow up friendly. Dulany is taking excellent care of him, and we feed him on milk and potatoes.

I have enjoyed meeting an old classmate of mine at Harvard. He was heavyweight boxing champion when I was in college.

I was much interested in your seeing the wild deer. That was quite remarkable. Today, by the way, as I rode along the beach I saw seals, cormorants, gulls and ducks, all astonishingly tame.

MORE TREASURES

Del Monte, Cal., May 10, 1903

BLESSED ARCHIE:

I think it was very cunning for you and Quentin to write me that letter together. I wish you could have been with me today on Algonquin, for we had a perfectly lovely ride. Dr. Rixey and I were on two very handsome horses, with Mexican saddles and bridles; the reins of very slender leather with silver rings. The road led through pine and cypress forests and along the beach. The surf was beating on the rocks in one place and right between two of the rocks where I really did not see how anything could swim a seal appeared and stood up on his tail half out of the foaming water and flapped his flippers, and was as much at home as anything could be. Beautiful gulls flew close to us all around, and cormorants swam along the breakers or walked along the beach.

I have a number of treasures to divide among you children when I get back. One of the treasures is Bill the Lizard. He is a little live lizard, called a horned frog, very cunning, who lives in a small box. The little badger, Josh, is very well and eats milk and potatoes. We took him out and gave him a run in the sand today. So far he seems as friendly as possible.

A HOMESICK PRESIDENT

Del Monte, Cal., May 10, 1903

DEAREST QUENTY-QUEE:

I loved your letter. I am very homesick for mother and for you children; but I have enjoyed this week’s travel. I have been among the orange groves, where the trees have oranges growing thick upon them, and there are more flowers than you have ever seen. I have a gold top which I shall give you if mother thinks you can take care of it. Perhaps I shall give you a silver bell instead. Whenever I see a little boy being brought up by his father or mother to look at the procession as we pass by, I think of you and Archie and feel very homesick. Sometimes little boys ride in the procession on their ponies, just like Archie on Algonquin.

LOVES AND SPORTS OF THE CHILDREN

Oyster Bay, Aug. 6, 1903

(To Miss Emily T. Carow)

Today is Edith’s birthday, and the children have been too cunning in celebrating it. Ethel had hemstitched a little handkerchief herself, and she had taken her gift and the gifts of all the other children into her room and neatly wrapped them up in white paper and tied with ribbons. They were for the most part taken downstairs and put at her plate at breakfast time. Then at lunch in marched Kermit and Ethel with a cake, burning forty-two candles, and each candle with a piece of paper tied to it purporting to show the animal or inanimate object from which the candle came. All the dogs and horses—Renown, Bleistein, Yagenka, Algonquin, Sailor Boy, Brier, Hector, etc., as well as Tom Quartz, the cat, the extraordinarily named hens—such as Baron Speckle and Fierce, and finally even the boats and that pomegranate which Edith gave Kermit and which has always been known as Santiago, had each his or her or its tag on a special candle.

Edith is very well this summer and looks so young and pretty. She rides with us a great deal and loves Yagenka as much as ever. We also go out rowing together, taking our lunch and a book or two with us. The children fairly worship her, as they ought to, for a more devoted mother never was known.

The children themselves are as cunning and good as possible. Ted is nearly as tall as I am and as tough and wiry as you can imagine. He is a really good rider and can hold his own in walking, running, swimming, shooting, wrestling, and boxing.

Kermit is as cunning as ever and has developed greatly. He and his inseparable Philip started out for a night’s camping in their best the other day. A driving storm came up and they had to put back, really showing both pluck, skill and judgment. They reached home, after having been out twelve hours, at nine in the evening. Archie continues devoted to Algonquin and to Nicholas. Ted’s playmates are George and Jack, Aleck Russell, who is in Princeton, and Ensign Hamner of the Sylph. They wrestle, shoot, swim, play tennis, and go off on long expeditions in the boats. Quenty-quee has cast off the trammels of the nursery and become a most active and fearless though very good-tempered little boy. Really the children do have an ideal time out here, and it is an ideal place for them. The three sets of cousins are always together.

I took Kermit and Archie, with Philip, Oliver and Nicholas out for a night’s camping in the two rowboats last week. They enjoyed themselves heartily, as usual, each sleeping rolled up in his blanket, and all getting up at an unearthly hour. Also, as usual, they displayed a touching and firm conviction that my cooking is unequalled. It was of a simple character, consisting of frying beefsteak first and then potatoes in bacon fat, over the camp fire; but they certainly ate in a way that showed their words were not uttered in a spirit of empty compliment.

A PRESIDENT AT PLAY

Oyster Bay, Aug. 16, 1903

(To Miss Emily T. Carow)

Archie and Nick continue inseparable. I wish you could have seen them the other day, after one of the picnics, walking solemnly up, jointly carrying a basket, and each with a captured turtle in his disengaged hand. Archie is a most warm-hearted, loving, cunning little goose. Quentin, a merry soul, has now become entirely one of the children, and joins heartily in all their plays, including the romps in the old barn. When Ethel had her birthday, the one entertainment for which she stipulated was that I should take part in and supervise a romp in the old barn, to which all the Roosevelt children, Ensign Hamner of the Sylph, Bob Ferguson and Aleck Russell were to come. Of course I had not the heart to refuse; but really it seems, to put it mildly, rather odd for a stout, elderly President to be bouncing over hay-ricks in a wild effort to get to goal before an active midget of a competitor, aged nine years. However, it was really great fun.

The other day all the children gave amusing amateur theatricals, gotten up by Lorraine and Ted. The acting was upon Laura Roosevelt’s tennis court. All the children were most cunning, especially Quentin as Cupid, in the scantiest of pink muslin tights and bodice. Ted and Lorraine, who were respectively George Washington and Cleopatra, really carried off the play. At the end all the cast joined hands in a song and dance, the final verse being devoted especially to me. I love all these children and have great fun with them, and I am touched by the way in which they feel that I am their special friend, champion, and companion.

A PREACHING LETTER

White House, Oct. 2, 1903

DEAR KERMIT:

I was very glad to get your letter. Am glad you are playing football. I should be very sorry to see either you or Ted devoting most of your attention to athletics, and I haven’t got any special ambition to see you shine overmuch in athletics at college, at least (if you go there), because I think it tends to take up too much time; but I do like to feel that you are manly and able to hold your own in rough, hardy sports. I would rather have a boy of mine stand high in his studies than high in athletics, but I could a great deal rather have him show true manliness of character than show either intellectual or physical prowess; and I believe you and Ted both bid fair to develop just such character.

There! you will think this a dreadfully preaching letter! I suppose I have a natural tendency to preach just at present because I am overwhelmed with my work. I enjoy being President, and I like to do the work and have my hand on the lever. But it is very worrying and puzzling, and I have to make up my mind to accept every kind of attack and misrepresentation. It is a great comfort to me to read the life and letters of Abraham Lincoln. I am more and more impressed every day, not only with the man’s wonderful power and sagacity, but with his literally endless patience, and at the same time his unflinching resolution.

PROPER PLACE FOR SPORTS

White House, Oct. 4, 1903

DEAR TED:

I am delighted to have you play football. I believe in rough, manly sports. But I do not believe in them if they degenerate into the sole end of any one’s existence. I don’t want you to sacrifice standing well in your studies to any over-athleticism; and I need not tell you that character counts for a great deal more than either intellect or body in winning success in life. Athletic proficiency is a mighty good servant, and like so many other good servants, a mighty bad master. Did you ever read Pliny’s letter to Trajan, in which he speaks of its being advisable to keep the Greeks absorbed in athletics, because it distracted their minds from all serious pursuits, including soldiering, and prevented their ever being dangerous to the Romans? I have not a doubt that the British officers in the Boer War had their efficiency partly reduced because they had sacrificed their legitimate duties to an inordinate and ridiculous love of sports.

A man must develop his physical prowess up to a certain point; but after he has reached that point there are other things that count more. I am glad you should play football; I am glad that you should box; I am glad that you should ride and shoot and walk and row as well as you do. I should be very sorry if you did not do these things. But don’t ever get into the frame of mind which regards these things as constituting the end to which all your energies must be devoted.

I am very busy now, facing the usual endless worry and discouragement, and trying to keep steadily in mind that I must not only be as resolute as Abraham Lincoln in seeking to achieve decent ends, but as patient, as uncomplaining, and as even-tempered in dealing, not only with knaves, but with the well-meaning foolish people, educated and uneducated, who by their unwisdom give the knaves their chance.

A RIDE AND A PILLOW FIGHT

White House, Oct. 19, 1903

DEAR KERMIT:

Yesterday afternoon Ethel on Wyoming, Mother on Yagenka and I on Renown had a long ride, the only incident being meeting a large red automobile, which much shook Renown’s nerves, although he behaved far better than he has hitherto been doing about automobiles. In fact, he behaved so well that I leaned over and gave him a lump of sugar when he had passed the object of terror—the old boy eagerly turning his head around to get it. It was lovely out in the country, with the trees at their very best of the fall coloring. There are no red maples here, but the Virginia creepers and some of the dogwoods give the red, and the hickories, tulip trees and beeches a brilliant yellow, sometimes almost orange.

When we got home Mother went upstairs first and was met by Archie and Quentin, each loaded with pillows and whispering not to let me know that they were in ambush; then as I marched up to the top they assailed me with shrieks and chuckles of delight and then the pillow fight raged up and down the hall.

VICE-MOTHER OF THE CHILDREN

White House, Nov. 15, 1903

DEAR KERMIT:

Mother has gone off for nine days, and as usual I am acting as vice-mother. Archie and Quentin are really too cunning for anything. Each night I spend about three-quarters of an hour reading to them. I first of all read some book like Algonquin Indian Tales, or the poetry of Scott or Macaulay. I have also been reading them each evening from the Bible. It has been the story of Saul, David and Jonathan. They have been so interested that several times I have had to read them more than one chapter. Then each says his prayers and repeats the hymn he is learning, Quentin usually jigging solemnly up and down while he repeats it. Each finally got one hymn perfect, whereupon in accordance with previous instructions from mother I presented each of them with a five-cent piece. Yesterday (Saturday) I took both of them and Ethel, together with the three elder Garfield boys, for a long scramble down Rock Creek. We really had great fun.

THE SUPREME CHRISTMAS JOY

White House, Dec. 26, 1903

(To his sister, Mrs. Douglas Robinson)

We had a delightful Christmas yesterday—just such a Christmas thirty or forty years ago we used to have under Father’s and Mother’s supervision in 20th street and 57th street. At seven all the children came in to open the big, bulgy stockings in our bed; Kermit’s terrier, Allan, a most friendly little dog, adding to the children’s delight by occupying the middle of the bed. From Alice to Quentin, each child was absorbed in his or her stocking, and Edith certainly managed to get the most wonderful stocking toys. Bob was in looking on, and Aunt Emily, of course. Then, after breakfast, we all formed up and went into the library, where bigger toys were on separate tables for the children.

I wonder whether there ever can come in life a thrill of greater exaltation and rapture than that which comes to one between the ages of say six and fourteen, when the library door is thrown open and you walk in to see all the gifts, like a materialized fairy land, arrayed on your special table?

THE MERITS OF MILITARY AND CIVIL LIFE

White House, Jan. 21, 1904

DEAR TED:

This will be a long business letter. I sent to you the examination papers for West Point and Annapolis. I have thought a great deal over the matter, and discussed it at great length with Mother. I feel on the one hand that I ought to give you my best advice, and yet on the other hand I do not wish to seem to constrain you against your wishes. If you have definitely made up your mind that you have an overmastering desire to be in the Navy or the Army, and that such a career is the one in which you will take a really heart-felt interest—far more so than any other—and that your greatest chance for happiness and usefulness will lie in doing this one work to which you feel yourself especially drawn why, under such circumstances, I have but little to say.

But I am not satisfied that this is really your feeling. It seemed to me more as if you did not feel drawn in any other direction, and wondered what you were going to do in life or what kind of work you would turn your hand to, and wondered if you could make a success or not; and that you are therefore inclined to turn to the Navy or Army chiefly because you would then have a definite and settled career in life, and could hope to go on steadily without any great risk of failure. Now, if such is your thought, I shall quote to you what Captain Mahan said of his son when asked why he did not send him to West Point or Annapolis. “I have too much confidence in him to make me feel that it is desirable for him to enter either branch of the service.â€

I have great confidence in you. I believe you have the ability and, above all, the energy, the perseverance, and the common sense, to win out in civil life. That you will have some hard times and some discouraging times I have no question; but this is merely another way of saying that you will share the common lot. Though you will have to work in different ways from those in which I worked, you will not have to work any harder, nor to face periods of more discouragement. I trust in your ability, and especially your character, and I am confident you will win.

In the Army and the Navy the chance for a man to show great ability and rise above his fellows does not occur on the average more than once in a generation. When I was down at Santiago it was melancholy for me to see how fossilized and lacking in ambition, and generally useless, were most of the men of my age and over, who had served their lives in the Army. The Navy for the last few years has been better, but for twenty years after the Civil War there was less chance in the Navy than in the Army to practise, and do, work of real consequence. I have actually known lieutenants in both the Army and the Navy who were grandfathersmen who had seen their children married before they themselves attained the grade of captain. Of course the chance may come at any time when the man of West Point or Annapolis who will have stayed in the Army or Navy finds a great war on, and therefore has the opportunity to rise high. Under such circumstances, I think that the man of such training who has actually left the Army or the Navy has even more chance of rising than the man who has remained in it. Moreover, often a man can do as I did in the Spanish War, even though not a West Pointer.

This last point raises the question about you going to West Point or Annapolis and leaving the Army or Navy after you have served the regulation four years (I think that is the number) after graduation from the academy. Under this plan you would have an excellent education and a grounding in discipline and, in some ways, a testing of your capacity greater than I think you can get in any ordinary college. On the other hand, except for the profession of an engineer, you would have had nothing like special training, and you would be so ordered about, and arranged for, that you would have less independence of character than you could gain from them. You would have had fewer temptations; but you would have had less chance to develop the qualities which overcome temptations and show that a man has individual initiative. Supposing you entered at seventeen, with the intention of following this course. The result would be that at twenty-five you would leave the Army or Navy without having gone through any law school or any special technical school of any kind, and would start your life work three or four years later than your schoolfellows of today, who go to work immediately after leaving college. Of course, under such circumstances, you might study law, for instance, during the four years after graduation; but my own feeling is that a man does good work chiefly when he is in something which he intends to make his permanent work, and in which he is deeply interested. Moreover, there will always be the chance that the number of officers in the Army or Navy will be deficient, and that you would have to stay in the service instead of getting out when you wished.

I want you to think over all these matters very seriously. It would be a great misfortune for you to start into the Army or Navy as a career, and find that you had mistaken your desires and had gone in without really weighing the matter.

You ought not to enter unless you feel genuinely drawn to the life as a life-work. If so, go in; but not otherwise.

JAPANESE WRESTLING

White House, March 5, 1904

DEAR KERMIT:

I am wrestling with two Japanese wrestlers three times a week. I am not the age or the build one would think to be whirled lightly over an opponent’s head and batted down on a mattress without damage. But they are so skillful that I have not been hurt at all. My throat is a little sore, because once when one of them had a strangle hold I also got hold of his windpipe and thought I could perhaps choke him off before he could choke me. However, he got ahead.

White House, April 9, 1904

DEAR TED:

I am very glad I have been doing this Japanese wrestling, but when I am through with it this time I am not at all sure I shall ever try it again while I am so busy with other work as I am now. Often by the time I get to five o’clock in the afternoon I will be feeling like a stewed owl, after an eight hours’ grapple with Senators, Congressmen, etc.; then I find the wrestling a trifle too vehement for mere rest. My right ankle and my left wrist and one thumb and both great toes are swollen sufficiently to more or less impair their usefulness, and I am well mottled with bruises elsewhere. Still I have made good progress, and since you left they have taught me three new throws that are perfect corkers.

WHITE HOUSE JOYS

White House, May 28, 1904

DEAR TED:

I am having a reasonable amount of work and rather more than a reasonable amount of worry. But, after all, life is lovely here. The country is beautiful, and I do not think that any two people ever got more enjoyment out of the White House than Mother and I. We love the house itself, without and within, for its associations, for its stillness and its simplicity. We love the garden. And we like Washington. We almost always take our breakfast on the south portico now, Mother looking very pretty and dainty in her summer dresses. Then we stroll about the garden for fifteen or twenty minutes, looking at the flowers and the fountain and admiring the trees. Then I work until between four and five, usually having some official people to lunch—now a couple of Senators, now a couple of Ambassadors, now a literary man, now a capitalist or a labor leader, or a scientist, or a big-game hunter. If Mother wants to ride, we then spend a couple of hours on horseback. We had a lovely ride up on the Virginia shore since I came back, and yesterday went up Rock Creek and swung back home by the roads where the locust trees were most numerous—for they are now white with blossoms. It is the last great burst of bloom which we shall see this year except the laurels. But there are plenty of flowers in bloom or just coming out, the honeysuckle most conspicuously. The south portico is fragrant with that now. The jasmine will be out later. If we don’t ride I walk or play tennis. But I am afraid Ted has gotten out of his father’s class in tennis!

ON THE EVE OF NOMINATION FOR PRESIDENT

White House, June 21, 1904

DEAR KERMIT:

Tomorrow the National Convention meets, and barring a cataclysm I shall be nominated. There is a great deal of sullen grumbling, but it has taken more the form of resentment against what they think is my dictation as to details than against me personally. They don’t dare to oppose me for the nomination and I suppose it is hardly likely the attempt will be made to stampede the Convention for any one. How the election will turn out no man can tell. Of course I hope to be elected, but I realize to the full how very lucky I have been, not only to be President but to have been able to accomplish so much while President, and whatever may be the outcome, I am not only content but very sincerely thankful for all the good fortune I have had. From Panama down I have been able to accomplish certain things which will be of lasting importance in our history. Incidentally, I don’t think that any family has ever enjoyed the White House more than we have. I was thinking about it just this morning when Mother and I took breakfast on the portico and afterwards walked about the lovely grounds and looked at the stately historic old house. It is a wonderful privilege to have been here and to have been given the chance to do this work, and I should regard myself as having a small and mean mind if in the event of defeat I felt soured at not having had more instead of being thankful for having had so much.

BIG JIM WHITE

White House, Dec. 3, 1904

BLESSED KERMIT:

The other day while Major Loeffler was marshaling the usual stream of visitors from England, Germany, the Pacific slope, etc., of warm admirers from remote country places, of bridal couples, etc., etc., a huge man about six feet four, of middle age, but with every one of his great sinews and muscles as fit as ever, came in and asked to see me on the ground that he was a former friend. As the line passed he was introduced to me as Mr. White. I greeted him in the usual rather perfunctory manner, and the huge, rough-looking fellow shyly remarked, “Mr. Roosevelt, maybe you don’t recollect me. I worked on the roundup with you twenty years ago next spring. My outfit joined yours at the mouth of the Box Alder.†I gazed at him, and at once said, “Why it is big Jim.†He was a great cowpuncher and is still riding the range in northwestern Nebraska. When I knew him he was a tremendous fighting man, but always liked me. Twice I had to interfere to prevent him from half murdering cowboys from my own ranch. I had him at lunch, with a mixed company of home and foreign notabilities.

Don’t worry about the lessons, old boy. I know you are studying hard. Don’t get cast down. Sometimes in life, both at school and afterwards, fortune will go against any one, but if he just keeps pegging away and doesn’t lose his courage things always take a turn for the better in the end.

WINTER LIFE IN THE WHITE HOUSE

White House, Dec. 17, 1904

BLESSED KERMIT:

For a week the weather has been cold—down to zero at night and rarely above freezing in the shade at noon. In consequence the snow has lain well, and as there has been a waxing moon I have had the most delightful evening and night rides imaginable. I have been so busy that I have been unable to get away until after dark, but I went in the fur jacket Uncle Will presented to me as the fruit of his prize money in the Spanish War; and the moonlight on the glittering snow made the rides lovelier than they would have been in the daytime. Sometimes Mother and Ted went with me, and the gallops were delightful. Today it has snowed heavily again, but the snow has been so soft that I did not like to go out, and besides I have been worked up to the limit. There has been skating and sleigh-riding all the week.

The new black “Jack” dog is becoming very much at home and very fond of the family.

With Archie and Quentin I have finished “The Last of the Mohicans,” and have now begun “The Deerslayer.” They are as cunning as ever, and this reading to them in the evening gives me a chance to see them that I would not otherwise have, although sometimes it is rather hard to get time.

PLAYMATE OF THE CHILDREN

White House, Jan. 4, 1905

(To Mr. and Mrs. Emlen Roosevelt)

I am really touched at the way in which your children as well as my own treat me as a friend and playmate. It has its comic side. Thus, the last day the boys were here they were all bent upon having me take them for a scramble down Rock Creek. Of course, there was absolutely no reason why they could not go alone, but they obviously felt that my presence was needed to give zest to the entertainment. Accordingly, off I went, with the two Russell boys, George, Jack, and Philip, and Ted, Kermit, and Archie, with one of Archie’s friends—a sturdy little boy who, as Archie informed me, had played opposite to him in the position of centre rush last fall. I do not think that one of them saw anything incongruous in the President’s getting as bedaubed with mud as they got, or in my wiggling and clambering around jutting rocks, through cracks, and up what were really small cliff faces, just like the rest of them; and whenever any one of them beat me at any point, he felt and expressed simple and wholehearted delight, exactly as if it had been a triumph over a rival of his own age.

NOVELS AND GAMES

White House, November 19, 1905

DEAR KERMIT:

I sympathize with every word you say in your letter, about Nicholas Nickleby, and about novels generally. Normally I only care for a novel if the ending is good, and I quite agree with you that if the hero has to die he ought to die worthily and nobly, so that our sorrow at the tragedy shall be tempered with the joy and pride one always feels when a man does his duty well and bravely. There is quite enough sorrow and shame and suffering and baseness in real life, and there is no need for meeting it unnecessarily in fiction. As Police Commissioner it was my duty to deal with all kinds of squalid misery and hideous and unspeakable infamy, and I should have been worse than a coward if I had shrunk from doing what was necessary; but there would have been no use whatever in my reading novels detailing all this misery and squalor and crime, or at least in reading them as a steady thing. Now and then there is a powerful but sad story which really is interesting and which really does good; but normally the books which do good and the books which healthy people find interesting are those which are not in the least of the sugar-candy variety, but which, while portraying foulness and suffering when they must be portrayed, yet have a joyous as well as a noble side.

A TRIBUTE TO ARCHIE

White House, March 11, 1906

DEAR KERMIT:

I agree pretty much to all your views both about Thackeray and Dickens, although you care for some of Thackeray of which I am not personally fond. Mother loves it all. Mother, by the way, has been reading “The Legend of Montrose” to the little boys and they are absorbed in it. She finds it hard to get anything that will appeal to both Archie and Quentin, as they possess such different natures.

I am quite proud of what Archie did the day before yesterday. Some of the bigger boys were throwing a baseball around outside of Mr. Sidwell’s school and it hit one of them square in the eye, breaking all the blood-vessels and making an extremely dangerous hurt. The other boys were all rattled and could do nothing, finally sneaking off when Mr. Sidwell appeared. Archie stood by and himself promptly suggested that the boy should go to Dr. Wilmer. Accordingly he scorched down to Dr. Wilmer’s and said there was an emergency case for one of Mr. Sidwell’s boys, who was hurt in the eye, and could he bring him. Dr. Wilmer, who did not know Archie was there, sent out word to of course do so. So Archie scorched back on his wheel, got the boy (I do not know why Mr. Sidwell did not take him himself) and led him down to Dr. Wilmer’s, who attended to his eye and had to send him at once to a hospital, Archie waiting until he heard the result and then coming home. Dr. Wilmer told me about it and said if Archie had not acted with such promptness the boy (who was four or five years older than Archie, by the way) would have lost his sight.

What a heavenly place a sandbox is for two little boys! Archie and Quentin play industriously in it during most of their spare moments when out in the grounds. I often look out of the office windows when I have a score of Senators and Congressmen with me and see them both hard at work arranging caverns or mountains, with runways for their marbles.

Goodbye, blessed fellow. I shall think of you very often during the coming week, and I am so very glad that Mother is to be with you at your confirmation.

A BIG AND LONELY WHITE HOUSE

White House, April 1, 1906

DARLING QUENTY-QUEE:

Slipper and the kittens are doing finely. I think the kittens will be big enough for you to pet and have some satisfaction out of when you get home, although they will be pretty young still. I miss you all dreadfully, and the house feels big and lonely and full of echoes with nobody but me in it; and I do not hear any small scamps running up and down the hall just as hard as they can; or hear their voices while I am dressing; or suddenly look out through the windows of the office at the tennis ground and see them racing over it or playing in the sandbox. I love you very much.

MORE ABOUT DICKENS

White House, May 20, 1906

DEAR TED:

Mother read us your note and I was interested in the discussion between you and over Dickens. Dickens’ characters are really to a great extent personified attributes rather than individuals. In consequence, while there are not nearly as many who are actually like people one meets, as for instance in Thackeray, there are a great many more who possess characteristics which we encounter continually, though rarely as strongly developed as in the fictional originals. So Dickens’ characters last almost as Bunyan’s do. For instance, Jefferson Brick and Elijah Pogram and Hannibal Chollop are all real personifications of certain bad tendencies in American life, and I am continually thinking of or alluding to some newspaper editor or Senator or homicidal rowdy by one of these three names. I never met any one exactly like Uriah Heep, but now and then we see individuals show traits which make it easy to describe them, with reference to those traits, as Uriah Heep. It is just the same with Micawber.

Mrs. Nickleby is not quite a real person, but she typifies, in accentuated form, traits which a great many real persons possess, and I am continually thinking of her when I meet them. There are half a dozen books of Dickens which have, I think, furnished more characters which are the constant companions of the ordinary educated man around us, than is true of any other half dozen volumes published within the same period.

ATTIC DELIGHTS

White House, June 17, 1906

BLESSED ETHEL:

Your letter delighted me. I read it over twice, and chuckled over it. By George, how entirely I sympathize with your feelings in the attic! I know just what it is to get up into such a place and find the delightful, winding passages where one lay hidden with thrills of criminal delight, when the grownups were vainly demanding one’s appearance at some legitimate and abhorred function; and then the once-beloved and half-forgotten treasures, and the emotions of peace and war, with reference to former companions, which they recall.

I am not in the least surprised about the mental telepathy; there is much in it and in kindred things which are real and which at present we do not understand. The only trouble is that it usually gets mixed up with all kinds of fakes.

PRIDE IN AMERICA

On Board U.S.S. Louisiana, Nov. 14

DEAR TED:

I am very glad to have taken this trip, although as usual I am bored by the sea. Everything has been smooth as possible, and it has been lovely having Mother along. It gives me great pride in America to be aboard this great battleship and to see not only the material perfection of the ship herself in engines, guns and all arrangements, but the fine quality of the officers and crew. Have you ever read Smollett’s novel, I think “Roderick Random” or “Humphrey Clinker,” in which the hero goes to sea? It gives me an awful idea of what a floating hell of filth, disease, tyranny, and cruelty a warship was in those days. Now every arrangement is as clean and healthful as possible. The men can bathe and do bathe as often as cleanliness requires. Their fare is excellent and they are as self-respecting a set as can be imagined. I am no great believer in the superiority of times past; and I have no question that the officers and men of our Navy now are in point of fighting capacity better than in the times of Drake and Nelson; and morally and in physical surroundings the advantage is infinitely in our favor.

It was delightful to have you two or three days at Washington. Blessed old fellow, you had a pretty hard time in college this fall; but it can’t be helped, Ted; as one grows older the bitter and the sweet keep coming together. The only thing to do is to grin and bear it, to flinch as little as possible under the punishment, and to keep pegging steadily away until the luck turns.

QUENTIN’S SNAKE ADVENTURE

White House, Sept. 28, 1907

DEAREST ARCHIE:

Before we left Oyster Bay Quentin had collected two snakes. He lost one, which did not turn up again until an hour before departure, when he found it in one of the spare rooms. This one he left loose, and brought the other one to Washington, there being a variety of exciting adventures on the way; the snake wriggling out of his box once, and being upset on the floor once.

The first day home Quentin was allowed not to go to school but to go about and renew all his friendships. Among other places that he visited was Schmid’s animal store, where he left his little snake. Schmid presented him with three snakes, simply to pass the day with—a large and beautiful and very friendly king snake and two little wee snakes. Quentin came hurrying back on his roller skates and burst into the room to show me his treasures. I was discussing certain matters with the Attorney-General at the time, and the snakes were eagerly deposited in my lap. The king snake, by the way, although most friendly with Quentin, had just been making a resolute effort to devour one of the smaller snakes. As Quentin and his menagerie were an interruption to my interview with the Department of Justice, I suggested that he go into the next room, where four Congressmen were drearily waiting until I should be at leisure. I thought that he and his snakes would probably enliven their waiting time. He at once fell in with the suggestion and rushed up to the Congressmen with the assurance that he would there find kindred spirits. They at first thought the snakes were wooden ones, and there was some perceptible recoil when they realized that they were alive. Then the king snake went up Quentin’s sleeve—he was three or four feet long—and we hesitated to drag him back because his scales rendered that difficult. The last I saw of Quentin, one Congressman was gingerly helping him off with his jacket, so as to let the snake crawl out of the upper end of the sleeve.

QUENTIN’S “EXQUISITE JEST”

White House, Jan. 2, 1908

DEAR ARCHIE:

Friday night Quentin had three friends, including the little Taft boy, to spend the night with him. They passed an evening and night of delirious rapture, it being a continuous roughhouse save when they would fall asleep for an hour or two from sheer exhaustion. I interfered but once, and that was to stop an exquisite jest of Quentin’s, which consisted in procuring sulphureted hydrogen to be used on the other boys when they got into bed.

They played hard, and it made me realize how old I had grown and how very busy I had been these last few years, to find that they had grown so that I was not needed in the play. Do you recollect how we all of us used to play hide-and-go-seek in the White House? and have obstacle races down the hall when you brought in your friends?