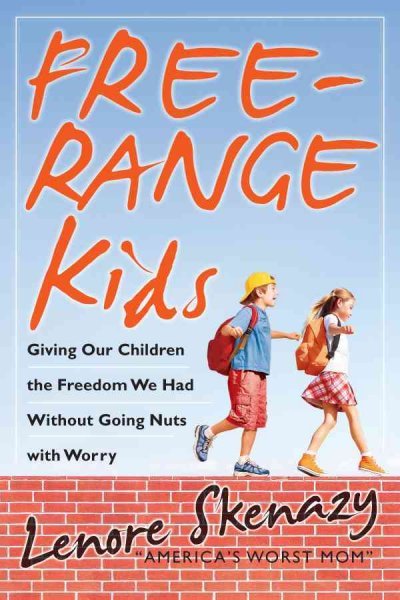

Last month we ran a four-part series about the origins and downsides of overprotective parenting and how to raise more independent kids. My guest on the podcast today was a key resource in that series and has been at the forefront of battling helicopter parenting for nearly a decade. Her name is Lenore Skenazy and she’s the author of Free-Range Kids: How to Raise Safe, Self-Reliant Children (Without Going Nuts with Worry).

Today on the show, Lenore and I discuss how being labeled “America’s Worst Mom†led her to become a leader of a movement to give kids more unsupervised time, the cultural shifts that have happened in the past 30 years that have resulted in overprotective parenting, and why, contrary to popular belief, the chance of your kid getting abducted by a stranger is actually incredibly small. Along the way, Lenore shares some crazy stories of parents getting in trouble with the law simply for letting their children play outside by themselves.

We end our conversation with some actionable steps you can take as a parent to raise independent, self-reliant kids and why it’s important for them to have as much unsupervised play as possible.

If you’re a parent or a parent-to-be, you don’t want to miss this hilarious, but informative episode.

Show Highlights

- The origins of the Free Range Kids movement

- Why people were so upset about Lenore letting her 9-year-old ride the subway alone

- The differences in parenting from a generation ago to today

- The “question” that Lenore despises every time she gets interviewed

- The perils of “Worst-First” thinking

- The miasma of fear that parents are breathing in every day

- Is this fear uniquely American?

- What are the actual odds of your child being abducted?

- The illusion of control that parents hang on to

- The data-fication of today’s children

- Why parents need to cut themselves more slack

- The impact of smartphones on modern parenting

- The societal impetus that encourages parents to call 911 when they see unsupervised kids

- Moral vs rational judgments in parents

- How kids are losing their imagination in this overprotective world

- The dangers of kids not being exposed to risk

- Ideas for how parents can balance risk and safety in raising their kids

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- The original article that got Lenore labeled the Worst Mom in America

- Lenore’s appearance on The Daily Show

- Overprotective Parenting series

- The Ikea sex trafficking story that went viral on Facebook

- The Nurture Assumption by Judith Rich Harris

- How Moral Judgments Distort Perceptions of Risk to a Child

- The Importance of Roughhousing With Your Kids

- Free to Learn by Peter Gray

- Free Range Kids Bill of Rights

- Free Range Kids Project for schools

If there are kids in your life, I highly recommend picking up a copy of Free-Range Kids. Lenore does a bang-up job debunking the myths out there about child safety. Plus, she’s dang funny. There were several times while reading the book that I literally lol-ed.

Connect With Lenore Skenazy

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Squarespace. Start your free trial today at Squarespace.com and enter code “manliness” at checkout to get 10% off your first purchase plus a free domain.

Blue Apron. Blue Apron delivers all the fresh ingredients and chef-created recipes needed so you can cook meals at home like a pro. Get your first three meals FREE by visiting blueapron.com/MANLINESS.

The Great Courses Plus. They’re offering my listeners a free one-month trial when you text “AOM†to 86329. You’ll receive a link to sign up and you can start watching from your smart phone… or any device immediately! (To get this reply text, standard data and messaging rates apply.)

Recorded on ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. And actually this is the 300th episode of the Art of Manliness podcast. Before we get to our show, just want to say thank you all who have been following the podcast for a few years now or have just come on.

It’s crazy, this thing that I started in 2009 and then stopped for a bit, then started back up again in 2013, has grown to be what it is today. We’re at a 50 million total downloads or plays overall since we’ve been doing this, and we get about one million downloads a month. So it’s just crazy. Thank you all for your continued support. Thanks for the letters with feedback and encouraging words. And thanks for sharing the show with your friends.

Here’s to 300 more episodes, and yeah, thanks.

So, let’s get to today’s episode. I’m really excited about it. Last month we ran a four-part article series on ArtofManliness.com about the origins and downsides of overprotective parenting, and how to raise more independent kids.

My guest today on the show was a key resource in that series and has been at the forefront of battling helicopter parenting for nearly a decade. Her name is Lenora Skenazy, and she’s the author of “Free Range Kids: How To Raise Safe, Self-Reliant Children Without Going Nuts With Worry.”

Today on the show, Lenora and I discuss how being labeled America’s worst mom led her to become a leader of a movement to give kids more unsupervised time. The cultural shift that had happened in the past 30 years that have resulted in overprotective parenting, and why contrary to popular belief, the chances of your kid getting abducted by a stranger is actually incredibly small.

Along the way, Lenora shares some crazy stories of parents getting in trouble with the law for simply letting their children play outside by themselves.

We end our conversation with some actional steps you can take as a parent to raise independent, self-reliant kids, and why it’s important for kids to have as much unsupervised play as possible. If you’re a parent or a parent-to-be, you don’t want to miss this hilarious but informative show.

After the show’s over, make sure to check out our show notes at AOM.is/freerangekids.

Lenora Skenazy, welcome to the show.

Lenore Skenazy: Thanks, Brett.

Brett McKay: So you are the author of a book called “Free Range Kids.” It’s all about encouraging parents to let their kids act independently, walk to school by themselves, play in the front yard by themselves. And this book kick-started a movement. The backstory of how this all started is interesting. How did a columnist from New York City start this whole movement of encouraging parents to let their kids wander off by themselves and do stuff by themselves?

Lenore Skenazy: The backstory is simple. I let my nine-year-old ride the subway by himself, he’d been asking me and my husband if we would let him do it. We’re on the subways all the time, we said yes. He took the subway, I wrote a column about it. And two days later I was on the Today Show, MSNBC, Fox News, and NPR. It’s rare you’re on both Fox News and NPR, let me just put it that way. Being described as this horrible mom who didn’t care if her son lived or died, I started a blog that weekend to say, “Uh, yes I do.”

Originally the thing on the side of my blog just said, I believe in safety. I believe in helmets and car seats and seat belts, and mouth guards. I wear extra layers. I just don’t think kids need a security detail every time they leave the house. And that just resonated with people. Both, “Yay! At last, somebody’s saying what I’ve been thinking,” and also, “Oh my god, she should have her kids taken away.”

Brett McKay: So let’s talk about the negative reaction. Why were people so upset about letting your nine-year-old ride the subway by himself? What’s going on there?

Lenore Skenazy: It’s so many things, I’m a general interest reporter. I’ve covered every possible topic from Barbie to bioterrorism. And suddenly I got stuck on the same topic now for almost 10 years. And what’s fascinating about it is, there is so much going on. Why would people think that a mother didn’t love her kid as much as someone watching the Today Show did, who said, “I wouldn’t do that, why would she?”

So the main thing going on is the idea that anytime a child is unsupervised, they are automatically in grave, mortal peril. That’s the new belief. And I didn’t believe this for the longest time, because it seems so strange. But I’ve had so many examples of people truly believing that over the past 10 years, that I’ve come to see that that is the bedrock of a lot of not only parenting beliefs, but school beliefs, and cop and CPS beliefs. The second a child is not in his mom’s sight lines, he’s doomed.

Brett McKay: But what’s going on, because I’m sure a lot of people who are listening to this podcast, they grew up, their moms just kicked them out of the house and said, “Don’t come back until dinnertime,” and they did all sorts … I did that. When I was five years old.

Lenore Skenazy: Everybody did that. Everybody said, “Oh, did you have a free range childhood?” I’m like, “I’m trying to find somebody who didn’t have a free range childhood.” We just didn’t call it that. You went outside, you were on your bike. If you were a guy, you were apparently, like you, I read your piece, you threw dirt clods at each other. And if you’re a girl, you played dolls and you went to the library, and a lot of jump-roping ensued.

What’s different is, I’ll give an example. When I was on the Today Show, and the subsequently for four years, I’d be asked this question in almost every interview. I still am. But it took four years for me to figure out what’s going on. At some point, the interviewer would lower his or her voice and look at me intently, unless it was by phone, which, I assume they were just looking intently at the mic. And say, “But Lenore, how would you have felt if he never came home?”

And I never knew what to say, because it was like, “I don’t know. I forgot to mention I have a spare son at home.” I do, he’s the older son. He hadn’t asked to go to the subway at age nine. I didn’t know what to answer and finally I realized why. It was because that “How would you have felt?” Thing is not a question. It’s an accusation. And the accusation is simply this: why weren’t you thinking about how bad you’d feel if he never came home, and therefore stopped yourself from letting him?

Because to be a good parent in America today, you are really supposed to be going to the deepest, darkest, scariest place, every time your children are out of your eyesight. And if you’re not going to that space, then there’s something wrong with you. You don’t care enough and other people care more, and they will let you know.

So I realized the thing I did that was really out of step, was I didn’t do what I now call “worst first” thinking. You go to the worst-case scenario first, and you proceed as if it’s likely to happen. To skip around, that’s why so many people are calling 911 the second they see a kid waiting in a car. They could be napping, they could be playing with an iPad, they could be reading. And they’re in front of the dry cleaners, and the mother is inside the dry cleaners with her back to the car for three seconds while she’s picking up the shirts. Maybe she turns around and waves.

It doesn’t matter. They think that in that short amount of time, the mom is not literally with them, something terrible is going to happen. They call 911 as if the mother had left her child and set the car on fire. And that’s the same thing, believe it or not. It’s this idea that the second you’re not with your kid, you are irresponsible because the child is going to die. I mean, I really wanted to write a second book, which I haven’t written and my agent says, “Don’t write this.” But I wanted to call it, “Quit Imagining Your Kids Dead,” because that is sorta what we’re exhorted to do as parents. And if you’re not doing that, you’re doing something wrong.

Brett McKay: Why do parents do this “worst first” thing?

Lenore Skenazy: Can I just say, I don’t want to start out talking about parents, and I don’t want to blame parents, because we are in a bind as parents. Because it’s an entire society that’s doing it. 19 states have laws that say you can’t let your kid wait in the car, even for a few minutes. Even on a non-hot day. Even with the air conditioning going. Even with everything perfect.

And so there’s a societal shift that thinks of children as in constant danger. And then there’s all these tech products that allow you to follow your kid while they’re walking to school, they’re a little dot on a Marauder’s Map. There’s ones for littler children that allow them to press a button and automatically call the police and you if ever they feel scared.

So there’s an entire miasma out there of fear that we are just breathing in every day. And parents always say, “Well, we’ve always been cautious, isn’t it the job of parents to try to keep their children alive? To care, to worry?”

And of course it is, and I feel the same way. But what’s different is this constant terror about the worst thing all the time. And that’s what I think of as this pollution that parents are stuck breathing in. Is your child at risk? Details at 7. What’s in their lunchbox? Details at 8. Are they being bullied? Details at 9. Can you let your child ride the school bus? Details at 10.

Everything is so scary. Everything is presented through the scrim of fear, we’re just breathing it in. And it’s no surprise that we would turn out to be more “helicopter parents.” We are living in a society that says if you’re not a helicopter parent, you’re doing something wrong. So let’s not talk about parents as if they’ve all gone individually crazy. It’s a society that’s gone crazy, and they can only see children through the lens of what terrible thing could happen to them.

Brett McKay: And is this an American phenomenon, or do you see this in other Western countries?

Lenore Skenazy: I wish it was just an American phenomenon. But I see it literally, I’m an American, I only speak English. But I do see it in the entire English-speaking world. Australia has all these laws. Parents get arrested for going in and paying for what they call petrol, we call gas. Paying for the gas and letting the kid wait in the car, oh my god, anything could’ve happened. And in England, it’s the same thing. Parents are arrested or hounded for letting their kids ride their bikes to school.

I think it’s pretty universal. I don’t think it’s necessarily in every struggling developing country. But in the countries that have time, money and media to spare, it seems really common.

Brett McKay: You were talking about the society, the milieu that we’re in. A lot of it’s the media, 24-hour news cycle, where anytime a missing child comes up, that becomes the main thing. Even though it’s very rare.

Lenore Skenazy: And they don’t even have to be missing. I don’t know if you saw the controversy that was going on two weeks ago, and then a week before that, and before that, before that. People are posting things on Facebook, the best example was one that was two weeks ago, a mom wrote on her Facebook, “Oh my god, you won’t believe what just happened!”

And you’re thinking, “Oh my god, what happened?”

She was at IKEA with three children, one of them in a baby bjorn, so one’s a baby, two are little kids, they’re all under age seven, she’s with her mother there. So it’s the grandma, the mom, and three kids. And she said, “And we were followed by men who were going to sex traffic my children. I just know it. Cause as we moved around the store, the men kept being there, and they kept looking at my children. And god forbid, if I had glanced down at my phone, I shiver to think at what might have happened, I am so lucky I didn’t look at my phone, because that way my children ended up safe and not sex trafficked.”

So what you have there is a story where literally nothing happened. She went to IKEA with her three children and her mother, she came home from IKEA with her three children and her mother, and while she was there, she saw some men and some men saw her. But this was shared, when I started writing about it, it had been shared 89,000 times and everybody underneath is writing, “Oh, this is great information, thank you. You’re so brave, so helpful, this is gonna help me, parents hold your children a little tighter.”

I’m like, “You can’t hold them tighter, one of them was literally strapped to her body, and the two others were there with her mom and their grandma in IKEA where you can’t get out even if you want to get out. You must go past every sham and every toppling dresser before you get to the meatballs.”

And yet this was treated as fact. So you’re just talking about a society that’s so hungry for these stories of terror and child kidnapping and perversion, that it will take a non-story and turn it into something that’s shared 100,000 times as if it’s valuable when it’s BS.

Brett McKay: Yeah, most of it’s BS. What are the actual chances that your child is going to get abducted by a stranger and sold into sex trafficking or be molested? What do the statistics actually say?

Lenore Skenazy: I’ll just give you the one statistic that I have in my book. And my book is 10 years old at this point, eight or nine years old. Crime, for the record, is back to the rate it was in 1963, which is a really safe time to live unless you were the President.

But here’s the deal. I had a guy crunch the numbers for me, because I’m not a good numbers person, and rather than saying it’s 1 in 1.5 million blah blah blah, because everybody says, “What if your child is the one?” I had him flip it.

So he figured out how long would you have to keep your child outside unattended for it to be statistically likely that they would be kidnapped by a stranger?

I’ll ask you, I don’t know if you’ve read my book, hopefully you have and hopefully you’ve forgotten the number. So how long do you think you have to keep your kid outside for it to be statistically likely. Sort of like how many lottery tickets do you have to buy for it to be statistically likely for you to win the lottery, how long would you have to keep the kid outside?

Brett McKay: I remember something like 700,000 days or something like that.

Lenore Skenazy: Years.

Brett McKay: 700,000 years. All right.

Lenore Skenazy: Yeah, actually the Times wrote it wrong. They put days, or hours or something. Hours is really confusing, because maybe there’s 700,000 hours in a week, I really don’t know. But no, it’s 750,000 years. After the first 100,000 it’s not really a kid anymore.

I’m not sure there’s a corporeal body after the first 100,000 years, I have a feeling it’s dust. But that should help some people visualize what a rare, rare crime we’re talking about.

But since statistics don’t really convince anyone of anything, I’ll say it, I’m happy to discuss how rare a crime child kidnapping by strangers is. But it doesn’t matter because even though it’s statistically rare, it is everywhere, everywhere else. It’s on Law and Order, it’s in every Kellerman mystery, it’s on every news channel, if they can get the story they will. If they don’t have a convincing or current story about a kid being kidnapped, then they’ll say it’s the 10th anniversary of, or whatever happened to? And there’ll be America’s Most Wanted and there’ll be To Catch a Predator.

So me talking about the infinitesimal odds is no match for society shoving this story down our throat.

Brett McKay: Right. And I fell prey to that, talked about …

Lenore Skenazy: So to speak. Oh my god. You were prey yourself.

Brett McKay: Right, right. But we talked about this in the story we wrote about on the blog, where my son Gus was out in the front yard, something we let him do, and then we went out there and he wasn’t there. And both my wife and I was like, “Oh my gosh. Someone has kidnapped him.”

Lenore Skenazy: I’ve done that too, gosh. Here I am, the free range mom, and I let my kid come home, and sometimes the after school activities were when it got dark. 15 minutes, your heart can plunge to places you didn’t realize were in your body. It is terrifying. If you’re breathing this stuff in, it’s hard not to think that way, because that’s what we’ve been trained to think.

That’s why when the ladies and I guess guys ask me on the TV shows, “How would you have felt if he never came home?”

That’s a catechism, that is you being trained to think that way. How would I feel, I was the one who let him play outside and now he’s dead and it’s all my fault. One thing that very much impressed me about your blog post was talking about how it’s not just fear and it’s not just the media, it’s not just the constant din of these terrible stories that they’ll drag up from wherever they can find.

It’s this idea also of blame, and this idea that if we only paid more close attention, our children would be perfectly safe, so that anytime a child is hurt, it must be because we totally failed. Our fear of that makes us believe that we just can’t let our kids go. It’s this belief that we can control our child’s fate, if we only pay complete and utter attention. And it’s not just nutter attention to watching them on the lawn, it’s everything they eat, and every person they talk to, and if they get on the bus we should know who they’re sitting next to so they’re not next to a bully.

But there’s this belief, I think it’s more common actually, in highly developed countries and in fact, people who have done well in life, you start thinking that, “I am in control. I got myself this good job, this good education, I have these nice kids,” and once you think that you really are master of your fate and of your child’s fate, the chances of something going wrong loom even bigger, because you of all people should have been able to prevent it.

And in that belief comes the need to watch them all the more closely. I don’t know if that’s making sense, but I think it’s the combination of believing you can control everything, makes you think you must control everything, and then pretty soon you can’t leave anything to chance, which means you can’t let your kid out of your sight.

Brett McKay: That idea, believing you can control everything, that’s kinda crazy, it is sort of insane to think that.

Lenore Skenazy: It is insane. Growing up, you’d laugh at people that had delusions that they were God, or something like that. But now we really think, think about what we can do. With technology, we can check every text our kids ever sent, check every email, look at every Instagram, hear every conversation, we can watch them through whatever it is, tagging them and watching where they go on a map. You can get in touch with them by calling them, or if not them you have their friend’s number, or their brother’s number and you call them.

So there’s actually an app, I can’t remember if it’s on Indiegogo or if it already exists, where you can match up how much and what your child ate that day, I guess maybe they have to input it, or maybe the thing listens to the crunching in your kid’s mouth, I have no idea. It also compares it to how much activity they’ve gotten, because of course with a Fitbit built into every phone, then you know how many steps they’ve taken and how many stairs they’ve climbed. And they’re trying to tell you that you can tinker with your child. Oh look, today they ate 17 more potato chips than they walked.

And so then you can press a button and make your kid, “Hey kid, before you come home today, in fact, while you’re inside today so I know you’re safe, you must do 17 more steps so that it balances out.” So you’re treating your kid almost like a robot or an app that you can tinker with. You can always be watching it, you can fix it if something is wrong. It’s not the old parental thing where you try to teach them some lessons and then you’re delighted when you find out that a few of them stuck. It’s constant supervision.

Brett McKay: And what’s funny, though, is we think we can do all these things to help our kids not just be safe, but be awesome. Be super smart, super athletic. But the research shows your kid’s gonna turn out the way he’s gonna turn out, and your input as a parent, it has an effect, but not as big as you think it’s gonna have.

Lenore Skenazy: Yeah. There’s a great book that came out oh gosh, 20 years ago called The Nurture Assumption, about how we assume it’s our nurture that creates our kids. And there’s always these fantastic stories of twins.

And my favorite one from this book was about an identical twin separated birth. One was raised in Trinidad to Jewish parents, and one was raised in Germany to Catholic parents. And when they finally met up god knows how, they looked at each other and they were both wearing aviator glasses, they both had applets, those little things on your shoulders that look like military decorations. They both read magazines starting at the back, going to the front. And they both flushed the toilet before they went to the toilet.

And so we wonder, gee. Do we think both sets of parents did exactly these things, or was this somehow pre-programmed? And I think you’re right. I think a lot of what we think of as our input on children is really just pre-programming.

Brett McKay: So that idea should relieve some parental anxiety. I think a lot of parents are freaking out about, I gotta get my kid into this preschool, I gotta have them watch Baby Einstein or whatever they’re doing nowadays so they’re super smart.

Lenore Skenazy: Yeah. I wish parents would cut themselves a ton of slack. Because we are in a society that is cutting them zero slack at all. What was I writing about yesterday? Oh.

There was this horrible story in Atlanta, it was at this rotating restaurant at the top of a tower. Everybody agrees, it was a couple feet from his parents, and somehow he got caught in the rotating mechanism and he died. It was just a tragic story. The restaurant has been around for over 35 years, this was the first and only time something like this happened.

And I looked at the first five comments on the Yahoo version of this story, and the first one was, “Parents watch your kids.” And the second one was, “What lazy parents, I bet they were looking at their phones.” And the third one was, “This is what happens when you don’t watch your kids, I would never let my kids out of my sight.” Fourth one was, “Excuse me, these people just experienced a tragedy, could we cut them a little slack?” And the fifth one was, “I never let my kids out of my sight, what were these parents thinking?”

So there’s not a lot of slack that parents are allowed to partake of these days. Everybody has an opinion, everybody thinks you’re doing it wrong. Everybody thinks that there’s no such thing as an accident, it all has to do with negligence, usually parental negligence.

And that’s why parents think that they must and they can control everything. Because they’re told that they can, that this was not a horrible accident. I told people, “Just believe in something else. Believe in God, or believe in fate or luck, but don’t believe that parents control everything. No human controls everything.” But we’re told we do.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that brings up an interesting point. Because I think a lot of parents, they want to encourage their kids to be these free range kids. Do things outside of their sight, but they’re not so much afraid of the kids getting hurt or abducted or whatever. They’re afraid that they’re gonna be the next social media story, where they’re just being publicly shamed.

Lenore Skenazy: But let me tell you, as a social media story, the social media story is one part of the equation. And the other part of the equation is that if somebody sees their kid outside unattended, because we all have cell phones, cell phones have such an interesting impact on parenting in this weird way, people who see a kid walking alone might think oh, that’s a little unusual.

But if they had to wait til they got home and picked up the phone and remembered to call the police, they would forget. But because they have the phone with them, and because everybody seems to believe they’re in the middle of a Jerry Bruckheimer movie, and they’re always seeing the most exciting, amazing sex trafficking or kidnapping in the making, they pick up the phone and say, “Oh my god, I just saw a child outside.”

And then they call the 911 operator, who feels like, “God, if anything bad happens, people are gonna know I was the 911 operator and I said who cares if a kid is walking home, it’s not that big a deal.”

So the 911 operator calls the police, and the police go there, and they’re part of this society too, they’re told that anytime a child is unsupervised they’re in danger, so they pick up the kid and then they pass it along to Child Protective Services. And Child Protective Services has no impetus to not be hysterical, in a way. Because if they shrug and say, “Oh this is just a kid walking home, I agree, I used to walk home at that age too, isn’t it great, they get to have some fresh air.”

They can think that, but they also think, “I better do a very thorough investigation, because now that this family has landed in front of me, if god forbid, the one in a million chances that something bad does happen to this kid afterwards, my name is on the report saying no big deal, they just let their kid walk home from school.”

And so at each step of the way, there’s no downside to overreaction from the anonymous caller, we’ve allowed anonymous calls to Child Protective Services since the 70s. From the caller to the 911 operator, to the police, to Child Protective Services, everyone has to cover their ass and nobody has ever called in and said, “Why did you start this gigantic investigation of a family simply because they believed that their 10-year-old was fine walking home from school, or their five-year-old was fine waiting in the car while mom got the pizza.”

Brett McKay: And that’s insane. I was watching a clip of you on Reason.com, where you’re talking about a study that shows that parents, when they do this, when they call protective services on another parent, they’re not so much concerned about the safety of the kid, they’re more concerned about the moral culpability of the parent.

Lenore Skenazy: Oh yeah. No, this is a fascinating study that was done at the University of California-Irvine. Frankly, based on my blog. And what they were interested in was, how come we keep arresting parents for putting their children in literally almost nonexistent danger, when a kid is waiting a few minutes in a car. And it’s not a kid waiting in the IBM parking lot, where you can reasonably assume somebody went into work and forgot the child, which is how kids die.

But when the kid is in front of the post office or the library.

So the study went this way. They told five different groups of people the same story, that a four-year-old was waiting in a car for half an hour. But they gave each different group a different scenario as to why the kid was in the car. And the first group was told that the kid was waiting in the car, the mom had gone to drop a book at the library but bam, she was hit by a Mack truck and she was knocked out cold for half an hour. Okay.

Second group is told that the mom had to do some work, something for her work. Third group is told she was exercising. Fourth group, she’s volunteering. And fifth group, that she spent that half an hour meeting up with her lover.

And then they asked these five groups, how much danger they thought that the child was in, in that half hour. And the most common answer was 10, on a scale of 1 to 10. No matter what, more people than anything else thought that the child was in complete and utter danger the entire time.

But when they did the average, the people that thought the child had been left in the car accidentally by a mom who was trying her darnedest to get right back to the kid but just couldn’t because of that Mack truck, they thought the kid was on a 6 of danger. People who knew that the mom had to go do something for her job, that kid was in a little more danger, they thought. And then the group that had been asked about the volunteering, a little more danger. Finally, the group that thought the mom had gone to visit her lover, ding ding ding! The kid was in massive, massive amounts of danger.

And what’s really interesting, is that it shows that when we think we’re being logical and we’re making a rational danger assessment, we are actually making a moral judgment. And the more immoral we judge the mom, the more danger we think she put the kid in. She meant to come back to the child, but she didn’t, that’s still a good mom. But she’s going off to meet her lover, that’s a bad mom. The kid is half an hour, either way. They’re waiting in the car without the mom. But somehow the mom that went off to meet her lover, has somehow left the kid in outrageous danger compared to the mom who was gonna turn right around and come right back to the car.

An interesting corollary to that study is, they did the same study but a smaller sampling. Asking those same five situations, but asking about a guy, a dad had been hit by the Mack truck, had to do something for work, blah blah blah. Went to meet his lover. And for the male, the danger that the people thought the child was in when the dad was hit by a truck or when the dad went to work was exactly the same.

So in other words, for dads, whether they’re knocked out cold or work, work is something that they must do, they have no choice. But for women, even women who had to do something for work, it was automatically, people started perceiving a little more danger, because why is she working instead of constantly keeping her eyes every single second on her child?

Which is why one of the things I try to point out about this model that we’ve been sold on, this helicopter, hovering, constant supervision model of parenting that no generation has ever had to do til now, is I think of it as a back door way of anti-feminism. Because nobody is saying “Women can’t work, they should be home watching children, they’ve got a God-given job to do and that is just to be a mother and a caregiver.”

Nobody says it that way. But they do say, “Okay, you’re out of work, you get home at 6, you pick up the kids, you go to the dry cleaner, you must take the triplets out of their car seats and drag them into the dry cleaner. Then you have to get them each a lollipop. Then you have to take the lollipop away, because it’s right before dinner. And then you have to put them back in the car seats, take off their snow suits because you’re not allowed to wear a coat in a car seat, and then strap them back in, and then get them back home and then take them all out again,” and nobody has said, “You’re not allowed to have a moment’s free time, that’ll teach you to work,” but we’ve said it’s for the safety of our precious children.

And somehow, for the safety of our precious children, mothers are spending hours and hours, I think the number’s actually nine hours more per week. That’s one whole working day per week, supervising their children, than they did back when fewer moms were working in the 70s.

Brett McKay: Right. So it seems like we’re guilting people into, oh, you’re not spending that much time with your kids, so you gotta spend more time with them and make it more arduous for you.

Lenore Skenazy: Right. It’s not like it’s this fun time, it’s a lot of schlepping.

Brett McKay: Right. So if parents shouldn’t worry about their kids getting abducted or hit by cars or if they’re walking home, things like that, what are some things parents should genuinely be concerned about when it comes to their kids’ safety?

Lenore Skenazy: Well, I’m concerned about some of the things that really are rising. Diabetes, and depression, possibly obesity, although I keep seeing conflicting reports on that. And those are things that happen when kids don’t have free time. When kids have free, unsupervised time, and they can go outside, and there are other kids who are getting free, unsupervised time, that they can play with, then they get fresh air, they get their yeah-yeahs out. They figure out something that literally interests them, whether it’s making a fort.

I spent hours, I don’t know why, looking for four-leaf clovers. I mean, there’s something they can fall into that they love that teaches them focus, or it’s a group activity and it teaches them how to get along with each other and how to compromise and how to hold themselves together, even if they’re frustrated, because that way the game can continue. I thought the ball was in, you thought the ball was out, but I want to keep playing, so I just, “Okay, ball’s out,” and then we keep playing.

So when we’re taking all those opportunities away from our kids, because we’re replacing them with structured, supervised activities that we think are safer, I think we’re making our kids less safe in terms of growing up. In play, you get so many life lessons that are gonna help you in terms of getting along with people. In little league you learn how to hit the ball, but in a sandlot game, you learn how to throw the ball a little easier to the kid who’s kinda klutzy, and you can practice doing it a goofy way, because nobody’s counting it, it’s not towards the little league championships.

You can be creative, you can afford to just be yourself. This is what I worry that we’re taking out of kids’ lives. This might be completely wrong, and this is an idea that was birthed this morning as my husband was leaving and he was talking about some of the people he worked with, they’re all very foodies, it’s a millennial thing to be a foodie, which I can understand. But he felt that they didn’t have a lot of other interests, and I worry that you don’t give kids the time to fall into chemistry, or to really love origami, or to make things or to write little stories. If they don’t have any of that free time, I’m not sure they end up fully developing.

So I do worry about that.

Brett McKay: I think it’s interesting too, you mentioned that by trying to protect our kids all the time, we’re actually making them less safe. They don’t know how to trust themselves or how to handle themselves when they’re actually on their own, when they’re 18 and in the real world by themselves, they don’t know how to handle themselves.

Lenore Skenazy: Well, everything takes practice. And if there’s an adult at the game, the adult will declare the teams, and the adult will decide if the ball is in or out. The adult will tell you, you have to go to the end of the line or whatever, but when it’s just kids, Peter Gray is one of my heroes, he wrote a book called Free to Learn. My god, interview him, he’s so wonderful.

But he points out that in adult-led activities, the adults are the adults. But when there’s no adults around, the kids learn how to be adults, they learn how to keep the game going, they learn how to teach the game. And if we keep taking those opportunities away from them, because we want them to be in something structured because first of all we think they’ll get better at the thing, and they probably will get better at whatever is being taught, like literally how to kick the ball.

But they don’t get better at organizing their friends, and coming up with something to do. So one idea that Peter and I had together, that is so simple that I would like people to consider doing, is since it’s hard to find other kids playing outside these days, that’s why people call 911 when they see a kid outside, it’s like seeing a lemur escape from the zoo. It’s like, what’s it doing out there?

Why not, after school, when there are all sorts of scheduled activities that your kids could go to, whether it’s soccer, or Mandarin, or piano, have the school leave the gym open and the playground open, and maybe put some boxes out there to build things with or some balls, jump ropes. And I guess for legal purposes you have to have some adult in the corner with the EpiPen, but other than that, have that person standing back, and here’s a chance for kids to finally have a quorum of other kids, mixed ages.

Mixed ages are great to play together because when you’re only with kids of your exact same age, it’s a little more competitive, but if you’re there with a younger kid, you turn a little softer and you teach that kid. And if you’re there with an older kid, you want to be the older kid, so you learn how to be a little more mature.

So you have mixed age kids together with no agenda, no adult calling the shots, and time. So you have the critical mass of kids, and you have a place for them to be together, and if you don’t pick them up til 6, it’s great for the working parent. There’s a place for the children to be, and it’s a facsimile of what our childhoods were, which is time after school that just happened to be outside the neighborhood and not at the playground.

Brett McKay: That’s a great idea. I love that.

Lenore Skenazy: I have two other important ideas that I’m trying to spread if you’re game.

Brett McKay: Oh, yeah. Spread them more.

Lenore Skenazy: Okay. One is to make sure like parents do not feel like, “I’d love to send my kid outside but what if I get arrested for negligence?”

I’m trying to get towns and states, either or, to pass the Free Range Kids Bill of Rights, which is one sentence long, and it simply says, “Our kids have the right to some unsupervised time, and we have the right to give it to them without getting arrested.” So that says it all.

We’re not going to say parents have a right to neglect their children, or to abuse their children. But if they think their kid is old enough to walk home from school, or like your Gus, your Gus walked at age six to his grandparents’ house half a mile away. If you think that Gus is ready to do that again, some bystander who calls 911 won’t get anywhere with turning you into a criminal, because all along the way, people will be allowed to say, “Yes, but the parent thought the child was ready,” and if the police are called in, the police say, “Hey, Gus. Do you know where you’re going?” “Yes?” “Do your parents know where you are?” “No.” “Okay. Well, do you know their number?” “Yeah.” “Okay, well, let’s call them.”

So you can intervene as a concerned citizen, but it doesn’t turn it into a criminal act on the parents’ part, trusting their kids to play outside or wait in the car for a few minutes on a non-boiling hot day, or come home as a latchkey kid.

So the Bill of Rights is not saying you have the right to neglect or abuse your kid, it just says you have the right to trust your kid, and we believe you know your kid better than we do, because you’re the parent.

So the Free Range Kids Bill of Rights is actually on my site, if you go to FreeRangeKids.com. At the top, there’s a little tab that says, FRK, Free Range Kids Bill of Rights.

Do you want to hear the other thing?

Brett McKay: Of course.

Lenore Skenazy: Quickly, the other thing is just the Free Range Kids, and you can change the name, I’m not completely megalomaniac about this, but the Free Range Project at schools is the teacher telling the kids in her class, go home today and ask your parents if there’s one thing that you feel that you’re ready to do, if you can do it, that maybe you haven’t done yet for one reason or another. It could be walk the dog, make dinner for the family, go run an errand, pick up your brother from school, whatever it is.

And because the school endorses it, and because it’s a one-shot deal, parents who let their kids walk once don’t necessarily have to let them do it again. The parents usually say yes, and from what I’ve seen, it’s only a handful of schools that have done this yet, but it is a screaming success. It is so amazing to me how outlandishly proud parents are when the kid comes back and they’re bringing home the milk, or they made the dinner, or they went and got themselves home.

The parents are at least as excited as the kids. And even though it is this one-shot deal, the simple fact of the matter is, once you see your kid walk, you don’t want them to go back to crawling. You don’t say, “Well, look, he’s taking his first steps, now go back to crawling.”

It’s the same thing when your kid runs an errand for you. You don’t say, “Well, that was great, never again.” You say, “Okay, and by the way, could you tomorrow go to grandma’s house?”

So it’s easy, it’s free, it takes no time at all. I do a lot of speaking, I speak at a lot of schools, and sometimes I speak to the kids at the school too, and the kids are wildly excited about doing this project. So it gives them freedom and it shows them that their parents aren’t just worried about them. It shows them that their parents have a little bit of belief in them, that they’re willing to say, “Okay, you are old enough to ride your bike to your friend’s house today, even though I hadn’t let you do that til now.”

Brett McKay: Awesome. Well, Lenore, this has been a great conversation. You mentioned people can find out more information about your work at FreeRangeKids.com, is that right?

Lenore Skenazy: You bet, yeah. Book, blog, Twitter speeches, everything is at FreeRangeKids.com.

Brett McKay: Awesome. Well, Lenora Skenazy, thank you so much for your time, it’s been a pleasure.

Lenore Skenazy: Oh, thank you Brett. And thank you for your essay. I thought that your part about control was really illuminating for me, that’s why I reread it. It was great.

Brett McKay: Well, thank you so much. My guest today was Lenora Skenazy, she’s the author of the book Free Range Kids, it’s available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere.

Also check out her website, FreeRangeKids.com, where you can find updates about crazy stuff that’s going on, parents getting in trouble for letting their kids be kids, as well as some resources that you can use in your community to encourage unsupervised play with your kiddos.

Also check out our show notes at AOM.is/freerangekids, where you can find links to resources, where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website, at ArtofManliness.com.

Also want to let you know we have a newsletter, a daily or weekly edition, you can sign up for that at ArtofManliness.com/newsletter. When you sign up, we’ll send you five free e-books, all designed to help you become a better man. Some really good ones there.

I recommend signing up for the weekly digest if you’re like me, you don’t like to get emails every day. We basically send you on Saturday of all the articles and podcast and other news going on, the ArtofManliness.com.

So again, ArtofManliness.com/newsletter. You’ll get five free e-books upon signing up, so go check that out. Thanks for continuing to support, and until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.