Today’s parents are empirically less likely to allow kids to explore their neighborhood alone, walk to school, play by themselves, and handle potentially dangerous tools or weapons, and more likely to closely supervise all of their children’s activities, than parents even one generation ago.

Last week we explored why this might be, and offered some hypotheses on the origins of the modern trend towards highly protective parenting.

We posited that its root traces to a variety of fears: the fear of litigation, the fear of peer disapproval, the fear of not spending enough time with one’s children to make them into successful, emotionally well-adjusted adults, and most of all, the fear of something bad happening to one’s kids so that they never even reach adulthood.

Indeed, when parents are asked why they are so protective of their children these days, so much more than even their own parents were of them just 30 or 40 years ago, many will respond that the world is simply a more dangerous place now than when they were kids.

Is this the case? Are children today more likely to be assaulted, kidnapped, or killed than they were a few decades ago?

Today we’ll take a nuanced look into the surprising answers to these questions.

Is the World a More Dangerous Place for Kids Than It Used to Be?

In an article appropriately titled, “There’s Never Been a Safer Time to Be a Kid in America,†The Washington Post presents some very useful graphs and stats that can help us assess whether or not it’s become riskier to let children play without supervision than it was several decades back.

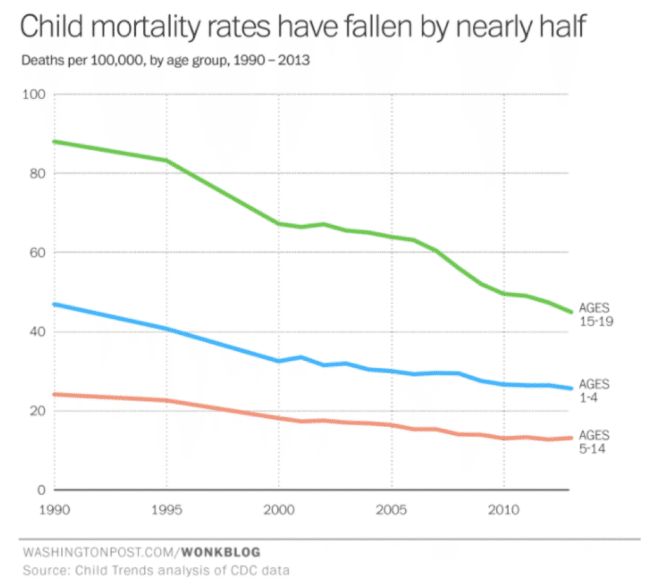

To begin with, the overall mortality rate of children in the United States has been in steady decline for the last 25 years — in fact, it’s never been lower:

Better medical interventions and more vaccinations explain part of this drop in childhood mortality, but not all of it, since the rate’s been declining even in the most recent decade, though standard vaccination regimens haven’t much changed in that time.

We also know that part of the decrease in the mortality of children empirically does have to do with a decline in traffic accidents and crimes, because there are stats that show that, too.

According to the National Highway Traffic Association, between 1993 and 2013 the number of juvenile pedestrians who were either injured or killed by being struck by a vehicle fell by about two-thirds — a dramatic drop made all the more dramatic when one considers that the U.S. population (and the number of vehicles on the road) rose over the same period.

Things are on the down and down regarding violent crimes against children as well. Between 1993 and 2004, violent assaults against children fell by an astonishing two-thirds (with sexual assaults declining even more). And as of 2008, the last year for which the Bureau of Justice Statistics has data available, the rate of child homicides stood at near-record lows.

Overall, the rates of crimes against children have in most cases sunk to levels at or below those of the 1970s, and the risk of a child dying from a crime, accident, or natural cause, which was negligible even 40 years ago, is even more so now; as the WaPo reports, “for a kid between the ages of 5 and 14 today, the chances of premature death by any means are roughly 1 in 10,000, or 0.01 percent.â€

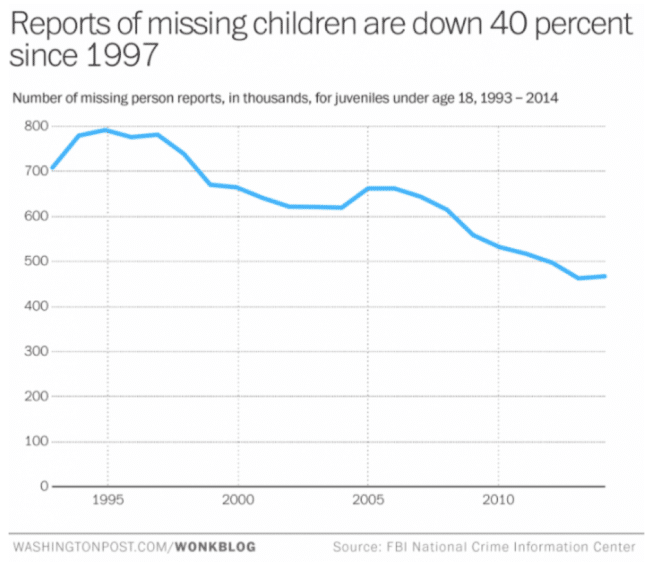

But what about the mother (and father) of all parental worries: the chances of your child going missing?

The rates are down there too — having dropped some 40% in the last two decades:

Again, keep in mind that the U.S. population rose by a third during this time, so that the actual rate of missing person reports fell even more than 40%.

It’s also important to understand that even among the cases of children going missing, very few fit the category of what’s called a “stereotypical kidnapping†— where a kid is abducted by a stranger by force. Among missing adults and children, 96% are actually runaways, with another percentage representing abductions by family members; only .1% of missing person cases are in fact true stranger kidnappings.

This percentage, as well as the overall chance of a child being abducted, has essentially held steady through the decades, standing at about 1 in 1.5 million. In Free Range Kids, Lenore Skenazy provides some incisive context for how truly tiny this risk is:

“The chances of any one American child being kidnapped and killed by a stranger are almost infinitesimally small: .00007 percent. Put yet another, even better way, by British author Warwick Cairns, who wrote the book How to Live Dangerously: if you actually wanted your child to be kidnapped and held overnight by a stranger, how long would you have to keep her outside, unattended, for this to be statistically likely to happen? About seven hundred and fifty thousand years.â€

Overall, then, fewer children are being killed by cars or murderers, or going missing, and the extremely rare chance of their being kidnapped is about the same as when you were a kid.

The world simply isn’t a more dangerous place now that it used to be.

Listen to my podcast with Lenore Skenazy about “free range” parenting:

But Is Crime Going Down Because Parents Have Become More Protective?

A rejoinder to the above data, and the idea that it’s never been safer to let your kids roam and play by themselves, is to posit that the whole reason traffic accidents and crimes against children have in fact gone down is because parents started to be so cautious in the 90s. That is, kids aren’t getting hit by cars because they’re not walking around the neighborhood anymore; kids aren’t being killed because they’re not leaving the safety of their backyard; and while kidnappings haven’t gone down, who knows if they would have gone up, if parents hadn’t been keeping such a close eye on their children.

Would then a return to the “free range†parenting policies of yesteryear only see the rates of childhood mortality rebound?

While it’s possible for this hypothesis to have some merit, it obviously cannot be proven one way or the other. Experts generally reject it though. They point to other factors as being more likely drivers of the drop in accidents and crime: better safety features in vehicles have made them less likely to hit kids; potential murders and kidnappings have been prevented by higher incarceration rates, or by greater access to anti-psychotic drugs for the mentally ill. The rise of cell phones may even be a factor; not so much because they allow parents to constantly be in contact with their kids, but because the mere possibility of their presence has seemingly acted as a deterrent to would-be, but risk-averse, criminals.

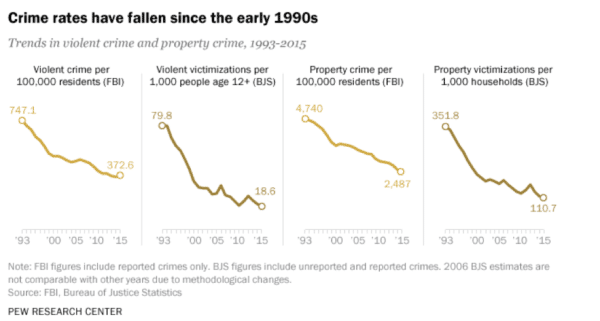

Evidence that cultural/societal factors beyond protective parenting are behind the decline in crimes against children can be seen in the fact that it isn’t the only kind of crime that’s down. As these graphs from the Pew Research Center show, since the early 1990s the rate for all crime — violent and non, against both children and adults — has plummeted between 50-77% (depending on what data is used):

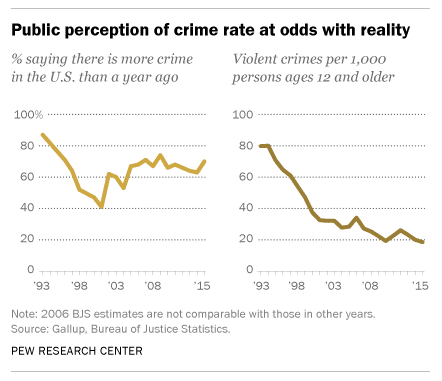

It’s interesting to note the gap that exists between reality and perception; even though the crime rate is down, people still believe that it’s up — a phenomenon that has likely been driven by the rise of 24/7 news, and the way modern television channels and websites lend crime (especially against children) an amount of coverage greatly disproportional to its actual occurrence.

Another way to assess the impact of protective parenting on keeping children safer is to look at the rate at which they’ve injured themselves at playgrounds over the last several decades; because playgrounds (and the way families use them) have changed in a way less influenced by confounding variables than society at large, they provide a good test case as to whether a greater emphasis on safety can significantly mitigate childhood risks.

Since the 1970s, municipal park departments have spent millions and millions of dollars revamping playgrounds to make their equipment as injury-proof as possible. Out have gone tall, metal jungle gyms, steep slides, monkey bars, and seesaws (without stabilizing ballasts in the center), along with the pavement, and even wood chips, covering the ground beneath them. In have been put plastic, low-level, prefab apparatuses, mounted atop rubber matting.

Yet despite the significant transformation of children’s play areas, the number of injuries and deaths resulting from them have hardly budged.

According to the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, the number of visits to hospital emergency rooms attributed to playground equipment (both home and residential) was 156,000 in 1980 and 271,475 in 2012. That seems like a big increase, but only if you forget to take into account the fact that the population of the U.S. rose by a third over the same time period. On a per capita basis, there was 1 playground-equipment-caused emergency room visit per 1,452 Americans in 1980, and 1 per 1,156 Americans in 2012 — a decrease of only .02%.

In other words, intensive efforts to safety-proof playgrounds, and closer supervision of children’s use of them by parents, have not made a significant impact on preventing injuries. If vigilant supervision of children in a contained area like a playground can’t move the ticker on this risk, then it stands to reason that vigilant supervision of children in general has not likely driven the dramatic drop in crimes against kids.

From the above data, we can reasonably draw the following conclusions:

- It’s a safer world today than when modern parents were kids, and that likely has little-to-nothing to do with the emergence of a more protective parenting style.

- The fact that the number of kidnappings hasn’t changed, and the number of playground-caused injuries has only marginally declined, shows that no amount of vigilance can prevent all tragedies and accidents; there’s a degree of randomness in the world that simply cannot be completely controlled.

- Even if we were to implausibly conclude that protective parenting has hypothetically driven all of the drop in childhood mortality, the crimes-against-children rate in the absence of this neo-vigilance would still only be back to the levels of the 1970s and 80s, which was negligible even then. So we’re back to the fact that the world is, at the very, very least, no more dangerous now than when modern parents were kids — and were allowed a degree of freedom denied today’s children.

Okay, these stats are interesting and all, but what if that 1 in 1.5 million is MY kid?

It’s hopefully mindset-shifting and comforting to know the stats outlined above, and that the world isn’t actually a more dangerous place than it used to be.

But that doesn’t mean there’s no risk in today’s world for children. The chance of a kid being abducted may be 1 in 1.5 million, but that’s still one real live, flesh and blood, cherubic child. The light and joy of some parents’ lives. Maybe the light and joy of your life.

Even if overprotective parenting could prevent just one serious injury or death, wouldn’t it be worth it? And even if the unchanging rate of kidnappings goes to show that such things are just completely random, and can’t be controlled even with the most strenuous of efforts, wouldn’t every parent simply feel better knowing they did everything they possibly could to prevent it from happening?

The answer to these questions would be an unequivocal yes…if protective parenting could be pulled off without any adverse side effects.

Unfortunately, however, the more we seek to nullify the risks of accidents and crimes befalling our children, the more we elevate the risk of significantly harming their bodies, minds, and spirits in other significant ways.

To the risk of NOT letting your kids do risky things, is where we will turn next time.

Read the Whole Series

The Origins of Overprotective Parenting

Is the World a More Dangerous Place for Kids Than It Used to Be?

The Risks of NOT Letting Your Kids Do Risky Things

3 Keys to Balancing Safety and Risk in Raising Your Kids

__________________________

Sources

Free Range Kids: How to Raise Safe, Self-Reliant Children (Without Going Nuts With Worry) by Lenore Skenazy

No Fear: Growing Up in a Risk Averse Society by Tim Gill

Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children From Nature-Deficit Disorder by Richard Louv

How to Raise a Wild Child: The Art and Science of Falling in Love With Nature by Scott D. Sampson

50 Dangerous Things (You Should Let Your Children Do) by Gever Tulley and Julie Spiegler

“The Overprotected Kid†by Hanna Rosin