A few days ago, I was playing some one-on-one basketball with my son Gus. As he was taking the ball back to our driveway’s “half-court line,†he stopped and said, “You know Dad, COVID has really changed our world really fast.â€

It’s an obvious observation, but when your nine-year-old articulates it, it stops you in your tracks for some reason.

Gus is right. The world has really changed really fast due to the global pandemic. And it continues to change rapidly and fluidly from week to week, and even day to day.

The global pandemic has reminded us that we live in a world of uncertainty.

Like a lot of people, I’ve done a fair amount of reflecting during this current crisis. Part of that reflection has turned me towards books that I’ve found helpful in understanding and managing uncertainty in the past. Their insights about dealing with a topsy-turvy world feel more salient than ever.

Below I share a list of those books that I’ve been revisiting and reflecting upon these past few weeks. They’re a mixture of non-fiction, fiction, and even scripture from different religions. What they all have in common is that they seek to answer the question that has plagued humans for millennia:

What am I supposed to do now?

These books have helped me answer that question for myself. Maybe you’ll find them helpful too — not just now, but in the future. For even though there are times when we feel the fickle fluctuations of the world more acutely, life has always been uncertain and always will be.

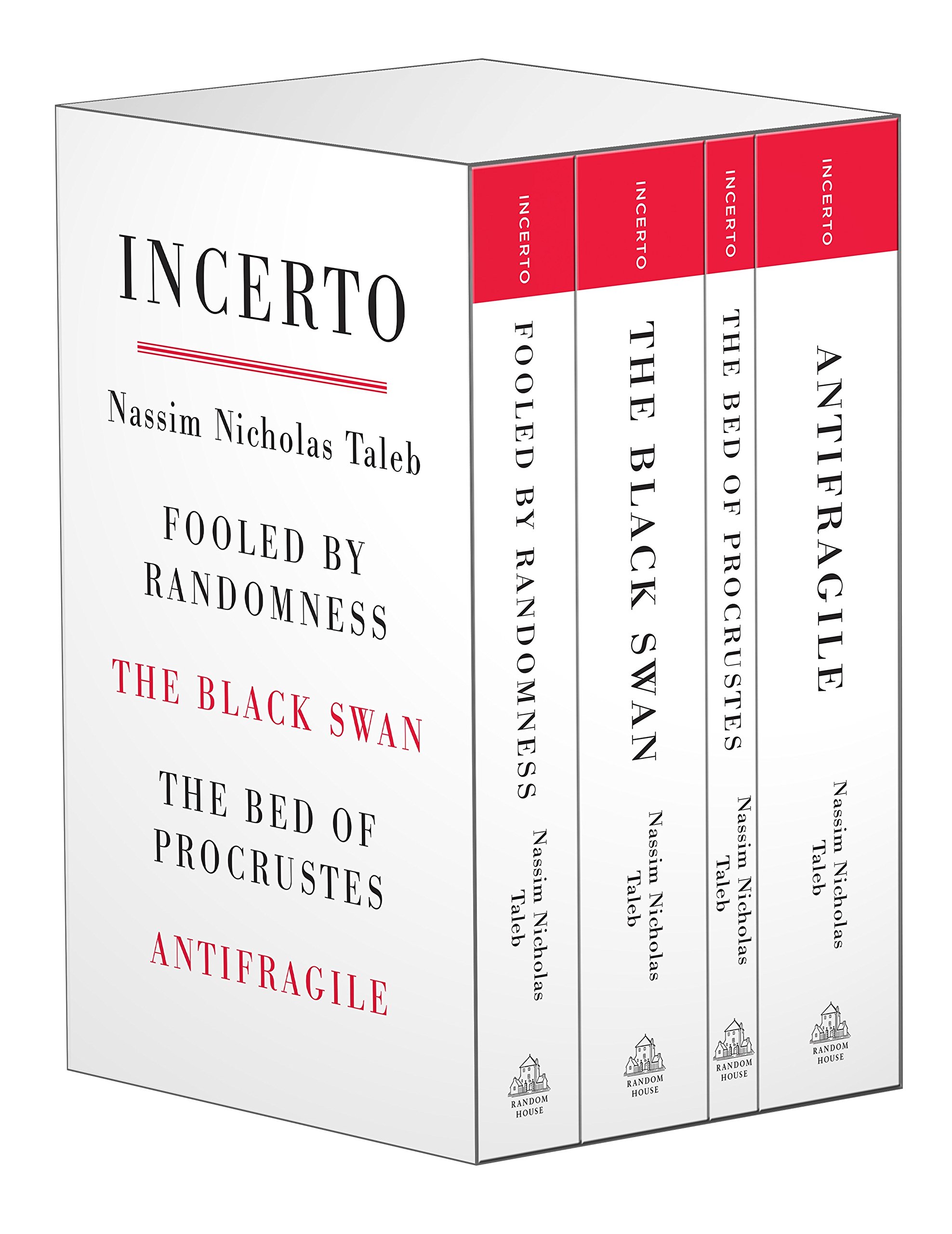

Incerto by Nassim Taleb

Since this box set came out, Skin the Game has been added to the series.

Incerto is a series of books philosopher and probability scholar Nassim Nicholas Taleb wrote that tackles the very issue of how to engage with an uncertain world. The first book, Fooled by Randomness, is about how we perceive (or fail to perceive) the role of chance and luck in our lives.

The next book in this series, The Black Swan, made famous the concept of black swans — unforeseen, unexpected events that have a significant impact on our lives and which are often later given retrospective explanations that make the events look less random and more predictable than they really were.

Antifragile then explores how to live and carry one’s self in a world of uncertainty. Taleb proposes strategies that will not only allow you to be resilient in the face of chaos and crisis, but actually grow from these countervailing forces as well.

The Bed of Procrustes is a book of aphorisms designed to expose and highlight the ways we humans fool ourselves into thinking we know what’s going on when we really don’t.

Skin in the Game is Taleb’s fifth and latest edition to his Incerto series, and in it, he explores the ethics of living in an uncertain world.

Taken together, these books provide a big picture roadmap of how to think about and deal with uncertainty. I’ve found myself picking them up a bit more during this pandemic. If you’re only going to read one volume in the series, I’d recommend Antifragile.

Be sure to check out my podcast with Taleb about Skin in the Game.

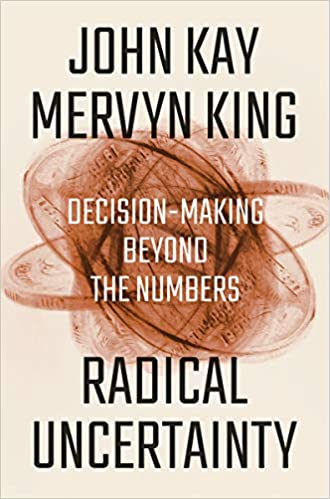

Radical Uncertainty by John Kay and Mervyn King

There are two types of uncertainty in the world. One type is the uncertainty of the insurance industry’s actuarial tables and the casino’s roulette game. This type of uncertainty represents a puzzle which can be navigated using the tools of probability theory.

The other type of uncertainty can’t be tamed with math. There are just too many factors interacting with each other in complex ways for probability theory to be of any use. This type of uncertainty is radical uncertainty.

In their book on the subject, economists John Kay and Mervyn King make the case that to grapple with radical uncertainty, you need to go beyond data and equations to develop a robust and resilient narrative about your current situation and to then continuously update it by asking yourself, “What is going on here?â€

Lots of great examples from the world of business and war. I found this book to be a useful supplement to Taleb’s Incerto series.

Science, Strategy, and War by Frans P.B. Osinga

Fighter pilot and philosopher John Boyd famously contributed the idea of the OODA Loop to military strategy. But while the OODA Loop is oft-cited, it is typically misunderstood as a superficial four-step process where the individual or group who makes it through all the stages the quickest wins.

If you truly understand the scientific and philosophical ideas Boyd references in his writing, you discover that the OODA Loop is actually a complex learning system — a multi-faceted method for dealing with uncertainty.

The problem is, it’s hard to suss out how Boyd’s concepts can be synthesized into this system, as he never wrote down his ideas about the OODA Loop in a formal paper; he only shared his thoughts in oral briefings.

That’s where Frans P.B. Osinga’s book Science, Strategy, and War comes in handy. Osinga painstakingly pieces together Boyd’s disparate briefs, notes, and lectures to show how the implications of the OODA Loop extend far beyond a simple four-step process. This is the best book I’ve read on the OODA Loop, and worth your study. For the CliffsNotes version, check out this article.

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

The capricious buffetings of uncertainty can wreak havoc on our emotions, leaving us feeling anxious, depressed, and helpless. Stoic philosophy can help us manage our emotions in times of uncertainty by prompting us to sort through what we can and cannot control, and instructing us to calmly endure the latter and focus on the former.

Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius was one of the last Stoic philosophers, and today is arguably the best known. Thanks to his personal writings that eventually became Meditations, Marcus left us with concrete guidance on how to put Stoicism into action. Thousands of years later, it’s still one of the best primers on Stoic philosophy, and is full of maxims that will help you steady your mind in the midst of chaos. Check out Jeremy’s takeaways from his first reading of it a few years back.

Greek Tragedies

For the Greeks, theatrical tragedies were more than just entertaining plays: they were a cathartic religious rite that trained the soul. While the storylines differed, philosopher Simon Critchley argues that all of the tragedies are about how to live in a world of ambiguity and uncertainty:

In play after play of the three great tragedians (Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides), what we see are characters who are utterly disoriented by the situation in which they find themselves. They do not know how to act. We find human beings somehow compelled to follow a path of suffering that allows them to raise questions that admit of no easy answer: What will happen to me? How can I choose the right path of action? The overwhelming experience of tragedy is a disorientation expressed in one bewildered and frequently repeated question: What shall I do?

While the tragedies don’t provide clear-cut answers to how to solve the mystery of uncertainty, they spur us to think hard about the nature of its vicissitudes. What’s more, they show us that even though we might feel disoriented, we still have to take action and move forward, just like the characters in these plays.

The Baghavad Gita

Sacred Hindu scripture, The Baghavad Gita begins in the middle of an apocalyptic war between families. A young warrior named Arjuna rides up to a battle about to unfold with his charioteer Krishna, a god in disguise.

Arjuna asks Krishna to stop. What Arjuna sees unnerves him: his own kin is gathered together to fight him. As a warrior, Arjuna is duty-bound to take part in the war, but he doesn’t want to raise a sword against his family. He cries out to Krishna, “Conflicting sacred duties confound my reason!†He continues his lament:

My limbs sink,

My mouth is parched,

My body trembles,

The hair bristles on my flesh.

The magic bow slips

From my hand,

my skin burns,

I cannot stand still,

My mind reels.

Arjuna sinks to the floor of his chariot, paralyzed by confusion as to what he should do.

The rest of the Gita is Krishna’s counsel to Arjuna on how to carry himself in a world of uncertainty. The big takeaway is the importance of taking action, while understanding and accepting that you have little or no control over the outcomes of your actions. Or, as Krishna puts it, “You have the right to work, but never to the fruit of work.â€

While we can’t completely control how things turn out, we can always control what we do. And control = courage.

Book of Job

When bad things happen to good people, we often find ourselves asking God or the universe, “Why?â€

The Book of Job throws that question back at us and asks, “Why not?â€

Job shows that misfortune can strike the just and the unjust, the good and the evil. And that while we can’t always control the whirlwind of fate, we still have control over how we react to it.

It’s no surprise that the Book of Job has been a favorite piece of literature for people who have had to deal with uncertainty on both a personal and a mass scale. Abraham Lincoln often turned to Job during his strife-filled presidency, and writer Joshua Wolf Shenk makes the case that it helped shape Lincoln’s spiritual worldview and understanding of the limits and responsibilities of human agency:

Lincoln responded with both humility and determination. The humility came from a sense that whatever ship carried him on life’s rough waters, he was not the captain but merely a subject of the divine force – call it fate or God or the ‘Almighty Architect’ of existence. The determination came from a sense that however humble his station, Lincoln was no idle passenger but a sailor on deck with a job to do. In his strange combination of profound deference to divine authority and a willful exercise of his own meager power, Lincoln achieved transcendent wisdom.

The Odyssey by Homer

The Odyssey is the tale of Odysseus’ ten-year journey home to Ithaca after the decade-long Trojan War. Along the way, he encounters one setback after another. Odysseus’ misfortune is so great that it leaves this epic hero in tears at times.

But he prevails.

Why? Because he is “the man of many wiles.†He’s resourceful, cunning, and adaptable. He understands that in a world of uncertainty, being rigid leads to destruction. You have to learn to bend. But most of all, you have to keep moving forward.

Now, it should be noted that Odysseus’ problems are mostly his own fault. If he hadn’t gotten cocky when he tricked the Cyclops, he might have made it home sooner. Perhaps that’s another lesson on uncertainty from The Odyssey: beware of hubris.

The Road by Cormac McCarthy

We’re going to be okay, arent we Papa?

Yes. We are.

And nothing bad is going to happen to us.

That’s right. Because we’re carrying the fire.

Yes. Because we’re carrying the fire.

In The Road an unnamed man and his son pilgrimage across a post-apocalyptic landscape, trying to find food, stay alive, and avoid capture by savage tribes of baby-eating barbarians. The father is sick and dying. He knows he won’t be around much longer. So he teaches his son skills he’ll need to survive. Most importantly, he teaches his son to “carry the fire.â€

Carrying the fire is a metaphor for living life nobly, even in the face of depravity. The Road is a reminder that even when the old rules have vanished, evil is on the march, and chaos reigns, we can still choose to be good. We can still keep up our standards. We can still make the right decisions.

I read this book once a year. It’s become my modern-day Greek-tragedy-esque ritual of catharsis.

Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry

If you’ve been following AoM long enough, you know that Lonesome Dove is my all-time favorite novel. I’ve read it five times and even named my son after one of the main protagonists, Augustus McCrae.

It wasn’t until about the third time reading Larry McMurtry’s 800+ page Western epic that I understood what kept me coming back to the book: It’s all about human beings trying to figure out what to do when they don’t know what to do. Like the Greek tragedies, Lonesome Dove is about encountering uncertainty.

One of the main characters, Woodrow Call, ponders the futility of plotting out the future after his crew experiences an early setback in their cattle drive from Southern Texas to Montana:

Though he had always been a careful planner, life on the frontier had long ago convinced him of the fragility of plans. The truth was, most plans did fail, to one degree or another, for one reason or another. He had survived as a Ranger because he was quick to respond to what he had actually found, not because his planning was infallible.

Surviving in a world of uncertainty requires you to adapt to the situation you find yourself in, rather than holding tightly to a vision of the world as you expected it to be. Woodrow understood you had to update your mental models if you wanted to make it in the unpredictable West.

And like the Greek tragedies and the Gita, Lonesome Dove teaches that even if you don’t know what to do, sometimes the only thing you can do is to keep moving forward. This is conveyed poignantly in a scene in which an Irish boy who’s joined the drive crosses a river and stirs up a swarm of water moccasins that kill him:

Call knelt by the boy, helpless to do one thing for him. It was the worst luck — to come all the way from Ireland and then ride into a swarm of water moccasins.

Call said nothing. The boy’s age had nothing to do with what had happened, of course; even an experienced man, riding into such a mess of snakes, wouldn’t have survived. He himself might not have, and he had never worried about snakes. It only went to show what he already knew, which was that there were more dangers in life than even the sharpest training could anticipate. Allen O’Brien should waste no time on guilt, for a boy could die in Ireland as readily as elsewhere, however safe it might appear.

‘It seems too quick,’ he said. ‘It seems very quick, just to ride off and leave the boy. He was the babe of our family,’ he added.

‘If we was in town we’d have a fine funeral,’ Augustus said. ‘But as you can see, we ain’t in town. There’s nothing you can do but kick your horse.’

Life sometimes rolls over us. Our choices are limited. But we still have the choice to get back on our horse and kick.

Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl

Viktor Frankl was a psychotherapist who was sent to Auschwitz for being a Jew. Upon entering the concentration camp, they took the last of his belongings, including his clothes, his wedding ring, and the manuscript of a book he was writing. By leaning on his rich inner life and helping other prisoners, along with some strokes of good luck, he lived to tell his story, which is a lesson about the control one has to make a bad situation not necessarily good, but survivable. Frankl teaches us that even when it seems like our choices are constrained, there remains an element of agency that can never be taken from us:

The last of the human freedoms: to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way. And there were always choices to make. Every day, every hour, offered the opportunity to make a decision, a decision which determined whether you would or would not submit to those powers which threatened to rob you of your very self, your inner freedom; which determined whether or not you become the plaything to circumstance, renouncing freedom and dignity.

“In a Far Country†by Jack London

This isn’t a book, but a short story — my all-time favorite short story — written by Jack London.

It follows the ill-fated tale of two men who set out to seek gold in the Klondike. These naive, indulgent, and inflexible city dwellers — “Incapables†as London calls the type — lack the skills and mindset to make it in the North and struggle to adapt their anticipated dream of easy wealth to the realities on the ground.

“In a Far Country†speaks to the importance of flexibility, attitude, and mental resilience; the true nature of romance and adventure; and that vital pillar of manhood — camaraderie and the willingness to pull one’s own weight in a group of men.

London scholar Earle Labor argues that “In Far Country,†particularly the beginning paragraphs, perfectly encapsulate Jack’s “Northland Code” — the qualities required to survive and thrive in the wilderness; they also perfectly encapsulate the qualities needed to survive and thrive in the landscape of uncertainty:

Tags: BooksWhen a man journeys into a far country, he must be prepared to forget many of the things he has learned, and to acquire such customs as are inherent with existence in the new land; he must abandon the old ideals and the old gods, and oftentimes he must reverse the very codes by which his conduct has hitherto been shaped. To those who have the protean faculty of adaptability, the novelty of such change may even be a source of pleasure; but to those who happen to be hardened to the ruts in which they were created, the pressure of the altered environment is unbearable, and they chafe in body and in spirit under the new restrictions which they do not understand. This chafing is bound to act and react, producing divers evils and leading to various misfortunes. It were better for the man who cannot fit himself to the new groove to return to his own country; if he delay too long, he will surely die.

The man who turns his back upon the comforts of an elder civilization, to face the savage youth, the primordial simplicity of the North, may estimate success at an inverse ratio to the quantity and quality of his hopelessly fixed habits. He will soon discover, if he be a fit candidate, that the material habits are the less important. The exchange of such things as a dainty menu for rough fare, of the stiff leather shoe for the soft, shapeless moccasin, of the feather bed for a couch in the snow, is after all a very easy matter. But his pinch will come in learning properly to shape his mind’s attitude toward all things, and especially toward his fellow man. For the courtesies of ordinary life, he must substitute unselfishness, forbearance, and tolerance. Thus, and thus only, can he gain that pearl of great price, — true comradeship. He must not say ‘Thank you;’ he must mean it without opening his mouth, and prove it by responding in kind. In short, he must substitute the deed for the word, the spirit for the letter.