1. Open book.

2. Read words.

3. Close book.

4. Move on to next book.

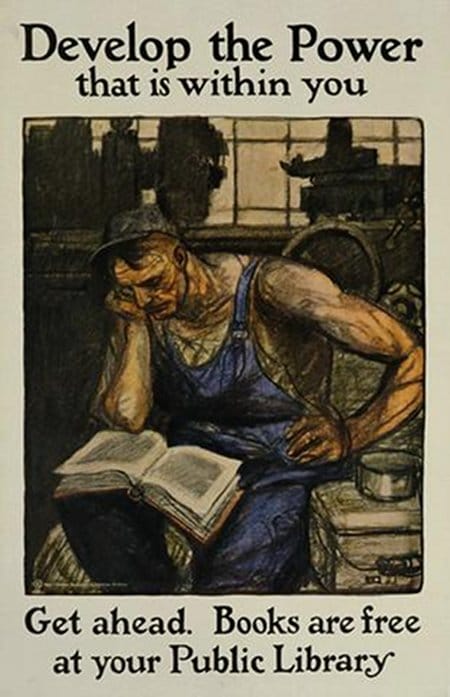

Reading a book seems like a pretty straightforward task, doesn’t it? And in some cases, it is. If you’re reading purely for entertainment or leisure, it certainly can be that easy. There’s another kind of reading, though, in which we at least attempt to glean something of value from the book in our hands (whether in paper or tablet form). In that instance, you might be surprised to learn that it’s not as simple as opening the book and reading the words.

Why Do We Need Instructions on How to Read a Book?

Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested. –Francis Bacon

In 1940, Mortimer Adler wrote the first edition of what is now considered a classic of education, How to Read a Book. There have been subsequent editions that contain great information, but the bulk of what we’ll be covering today is from Adler’s words of advice from nearly 75 years ago.

He states that there are four types of reading:

- Elementary — This is just what it sounds like. It’s what we learn in elementary school and basically gets us to the point that we can understand the words on a page and read them, and follow a basic plot or line of understanding, but not much more.

- Inspectional — This is basically skimming. You look at the highlights, read the beginning and end, and try to pick up as much as you can about what the author is trying to say. I’ll bet you did plenty of this with high school reading assignments; I know I did. Think of SparkNotes when you think of inspectional reading.

- Analytical — This is where you really dive into a text. You read slowly and closely, you take notes, you look up words or references you don’t understand, and you try to get into the author’s head in order to be able to really get what’s being said.

- Syntopical — This is mostly used by writers and professors. It’s where you read multiple books on a single subject and form a thesis or original thought by comparing and contrasting various other authors’ thoughts. This is time and research intensive, and it’s not likely that you’ll do this type of reading very much after college, unless your profession or hobby calls for it.

This post will cover inspectional and analytical reading, and we’ll focus mostly on analytical. If you’re reading this blog, you likely have mastered the elementary level. Inspectional reading is still useful, especially when trying to learn new things quickly, or if you’re just trying to get the gist of what something is about. I won’t cover syntopical reading in this post, as it’s just not used much by Average Joe Reader.

Analytical reading is where most readers fall short. The average high schooler in America reads at a 5th grade level, and the average adult American reads somewhere between the 7th and 8th grade levels. This is where most popular fiction actually falls. For men, think Tom Clancy, Clive Cussler, Louis L’Amour, etc. These are books that are incredibly entertaining, and a great way to spend a weekend afternoon, but if we’re honest with ourselves, don’t challenge our intellect all that much. There are some fine examples of manhood in those characters to be sure, but the point is that you won’t get more out of reading them once than you will out of reading them five times. It’s also why these are the types of books that are always on the bestseller lists — they cater to the level that most Americans can actually read at.

How come people can’t read at a higher level? Are we a society full of dopes? Hardly. Adler argues that the reason actually lies in our education. Once we reach the point of elementary reading, it’s assumed that we can now read. And to a point, we can. But we never actually learn how to digest or critique a book. So we get to high school and college and get overloaded with reading assignments that we’re supposed to write long papers about, and yet we’ve never learned how to truly dissect a book and get the most value out of it.

That’s our task today with this post. Again, I’ll mostly cover analytical reading, but I’ll also touch on inspectional reading, and a couple other related tidbits as well.

Inspectional Reading

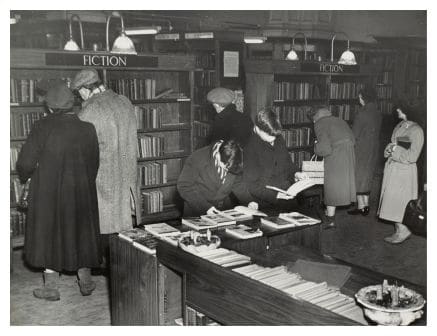

As mentioned above, there are certainly times when inspectional reading is appropriate. It’s particularly useful when you’re at the bookstore trying to pick out your next book and deciding if the unknown object in front of you is worth the dough. (The good news is that you can also do this with ebooks — in most cases you can scan the cover, the table of contents, the introduction, etc. before actually buying.) This type of reading is also handy when trying to learn new things quickly, or when you’re just trying to get the gist of something. It’s great for the kind of reading you should be doing to stay current in your career as well; books related to a certain industry can often be full of fluff and chapters that just don’t apply to your particular job, and inspectional reading lets you glean the things that are actually helpful without wasting time on irrelevant material.

As mentioned above, there are certainly times when inspectional reading is appropriate. It’s particularly useful when you’re at the bookstore trying to pick out your next book and deciding if the unknown object in front of you is worth the dough. (The good news is that you can also do this with ebooks — in most cases you can scan the cover, the table of contents, the introduction, etc. before actually buying.) This type of reading is also handy when trying to learn new things quickly, or when you’re just trying to get the gist of something. It’s great for the kind of reading you should be doing to stay current in your career as well; books related to a certain industry can often be full of fluff and chapters that just don’t apply to your particular job, and inspectional reading lets you glean the things that are actually helpful without wasting time on irrelevant material.

You can often get a pretty good feel for a book with inspectional reading by following the steps below. (To get the most out of this, you can actually follow along with a book off your shelf — it will only take 5-10 minutes.):

- Read the title and look at the front and back covers of the book. This seems obvious, but if you pay attention, you can glean much more than you would have originally thought from just the cover of the book. What’s the title? Spend 10 seconds thinking about the title and subtitles. What is it telling you? We often glance over titles, but they often offer deep insight into the meaning of the book. I think of some of the classics I’ve recently read, The Sun Also Rises, The Grapes of Wrath, even Frankenstein. There’s more to these titles than meets the eye. In that last example, I’m told that the book is really more about Victor Frankenstein than about the monster he creates. It’s more about his human character than about horror. Are there images on the cover? What could those images be conveying? An incredible amount of time and money goes into cover art, so don’t neglect it. What does the blurb on the back of the book say? We often quickly scan these, but if we’re paying attention, they give us a great, succinct plot that often reveals what the book is truly about. Now it should be said that sometimes titles, cover art, and blurbs are designed more for marketing and increasing sales than they are about accurately conveying the ideas of the book, but they can usually still provide us with valuable clues as to the book’s content.

- Pay special attention to the first pages of the book: the table of contents, the preface, the prologue, etc. These are incredibly useful pages. The table of contents will give you an outline of the entire book, which with non-fiction can tell you much of what you need to know right there. It’s a little harder with fiction, and many novels don’t have a table of contents, but take advantage of the ones that do. Especially with novels that are considered classics, you’ll often get all kinds of introductions and prefaces. For instance, my 50th anniversary one-volume edition of The Lord of the Rings has a very detailed three-page table of contents. That’s followed by a “Note on the Text†that gives me a bit of its publishing history and Tolkien’s process in writing. I then have a “Note on the 50th Anniversary Edition†that tells me that certain changes were made using Tolkien’s notes and journals. There’s then a foreword from Tolkien himself that tells a little bit of his own purpose in writing. And then I get to the prologue, which is part of the book itself. Even reading just the first sentence tells me, roughly, what the entire series is about: “The book is largely concerned with Hobbits, and from its pages a reader may discover much of their character and a little of their history.â€

- For non-fiction, skim headings and read the concluding chapter. The headings will actually often tell you the bulk of what you need to know of any non-fiction book. The text beneath the headings is often just fleshing out that main thought or theme. You can also read the conclusion to get a feel for what the author thought the main purpose or point of the book was. This is a little harder with fiction, as you don’t often get much for headings (outside of chapter titles), and at least for me, I certainly don’t want to know the end of the book. Although, I do know a fair amount of people who do; I still don’t understand that.

- Consider reading some reviews of the book. Your most likely destination will be Amazon. Often the top-rated review on Amazon offers a lot of information about the book – a summary and/or some of the book’s strengths and weaknesses. Unfortunately, you also have to take Amazon reviews with a grain of salt. Some negative reviews are from people who perhaps read a chapter and didn’t like something (see below regarding how to critique a book), or didn’t read the book at all! And sometimes people simply have an axe to grind against the author and are trying to “sabotage†them. And sadly when it comes to positive reviews, authors and publishers these days will sometimes pay for fake reviews of the book (a good clue for this is a whole boatload of 5-star reviews posted on the very same day/week the book is released). So look at the aggregate rating the book has received, then read a few 5-star, 3-star, and 1-star reviews and evaluate their credibility in order to get a better overall sense of the quality of the book.

Analytical Reading

You don’t need to do this type of reading for just anything. Only undertake it if you really want to get the most out of the book in front of you. Even Adler mentioned that not every book deserves this thorough treatment. But, many do. To read a great book and simply throw it back on the shelf to collect dust is in many ways a waste. The tips below apply to both fiction and non-fiction, but I’ll note where something may differ.

Let’s find out how to get the most out of what we read:

First, look up a bit about the author and the other books he/she has written. This is a personal thing. Before I pick up a book, I almost always look up the author and/or the book itself on Wikipedia. I like to know how old the writer is, what some of his or her motivations were, how autobiographical it may be if it’s a novel (you’d be surprised how many are), etc. This just gives you a little context into the author’s life that will hopefully help you understand the book a little better.

Second, do a quick inspectional reading. This is partially why I wanted to cover inspectional reading in the first place. A good, thorough reading of any book will include it. Look at the cover, always read the opening pages, etc. I know far too many people who never read introductions and just get right into page one. You’re skipping the valuable information that can actually frame the entire way you read the book. You don’t need to jump ahead to the conclusion, but at least get all that you can out of the cover and those opening pages.

Third, read the book all the way through, somewhat quickly. Adler actually calls this a “superficial readingâ€; you’re simply trying to digest the overall purpose of the book. Now, this doesn’t necessarily mean speed-reading. It more means that you won’t stop and scrutinize the meaning of each and every paragraph. It means that when you get stuck in a place that’s hard to understand, you’ll keep on going anyway. It means that when the story slows down a little and gets boring, you don’t just read 10 pages a day, but you’ll keep powering through with the purpose of understanding the flow of the book as well as you can right off the bat. In this reading you are underlining or circling or taking notes on things you have questions about, but you aren’t looking into those questions just yet. When you’re done with the book, go back through and look at what you underlined or circled or took some notes about. Try your best to answer a few of those questions you had. If you have the time and desire, re-read the whole thing again. I often do a semi-quick reading like this for many classics that I’m reading for the first time, but then I’ll go back a few months later (okay, sometimes it ends up being years) and read it a little more slowly.

This is where many people struggle with reading older or more complicated books. You might stop 50 pages into The Iliad because you’re just too confused about the language and the style. It’s actually best to just power through that and understand what you can, and then come back to your misunderstandings later. Better to have some knowledge than none at all.

Fourth, use aids, only if you have to. If there is a word you don’t know, first look at the context to try to discern its meaning. Use your own brain to get things going. If it’s something you simply can’t get past, or the word is clearly too important for you to glance over, then pull out the dictionary. If there’s a cultural reference that you can tell is important to understanding the particular passage, Google it. The main point is that you can use the tools around you, but don’t lean on them. Let your brain work a little bit before letting Google work for you.

Fifth, answer the following four questions as best as you can. Now, these questions could have been listed as the first step, as you should keep these in mind from the second you start reading. But, they quite obviously can’t be answered until you’ve read the book. This, Adler says, is actually the key to analytical reading. To be able to answer these questions shows that you have at least some understanding of the book. If you can’t answer them, you probably haven’t quite paid attention well enough. Also, it’s my opinion that you should actually write (or type) these answers out. Consider it to be like a book journal. It’ll stay with you and become much more ingrained than if you just answer them in your head.

- What is the book about, as a whole? This is essentially the back cover blurb. Don’t cheat, though. Come up, in your own words, with a few sentences or even a paragraph that describes what the book is about. This can actually be surface level; you don’t have to dig too deep. For instance, boy meets girl, boy falls in love with girl, boy makes stupid mistake and distances himself from girl, boy redeems himself and gets the girl.

- What is being said in detail, and how? This is where you start to dig a little deeper. When you’re done with that first reading of the book, Adler recommends writing an outline of the book yourself so you get a feel for its organization and overall tenor. Briefly go back and page through the book, jogging your memory of the key points. With non-fiction, outlining is pretty straightforward. With fiction, you could do it by chapter or by setting/scene. By chapter you would simply list the chapter numbers/names and a couple sentences of what it’s about. For books with very short chapters, it could even just be a few words. For setting/scene, you just follow the characters around and say what happened of significance there. I just finished The Sun Also Rises, which could be segmented into its various settings: Paris, the fishing trip, Pamplona, and post-Pamplona where the characters go their separate ways.

- Is the book true, in whole or in part? These last two questions are where we get to the meat of reading. As before, for non-fiction, this is a relatively easy (or at least easier) question to answer. Is what the author said true? Are the facts they presented true? With fiction, it’s more about asking if what was written is true to the general human experience, or even to your own experience. In The Great Gatsby, is that feeling of loss and the futileness of great wealth true to the human experience? I would certainly say so. This is partly what turns great books into classics. They ultimately speak to the most basic truths of humanity in story form.

- What of it? What’s the significance? If the book is indeed saying something true about the human experience, or about manliness, what’s the takeaway? If something strikes a chord with you, and you do nothing with it, it becomes at least partially wasted. There is something to be said about literature that stands on its own merits of simply being great literature, like art, but I’ve learned there is almost always a takeaway. Or at least a way in which you may think differently about the world. My understanding of life in America during the Dust Bowl was greatly increased after reading The Grapes of Wrath. There wasn’t necessarily something I would do in reaction to it, but my appreciation for farmers and farming families of that time period certainly grew. That’s definitely a valuable takeaway.

Sixth, critique and share your thoughts with others. Notice that this step is dead last. Only after having read the entire book, and thoughtfully answered the questions above, can you critique or have meaningful discussions about the book. When reading Amazon reviews, it’s clear when someone stopped reading three chapters in and gave a terrible review. Be extra careful about coming right out and saying, “I understand the book.†You can certainly understand parts of a book, but to have no questions at all probably means that it wasn’t actually a good book to start with, or you are full of yourself. When discussing, be precise in your areas of agreement or disagreement. To simply say, “This is stupid,†or, “I don’t like it,†offers nothing to a conversation. Also know that you don’t have to agree or disagree with everything about or in a book. You can love some parts and really dislike others.

Now you’ve read a book for all its worth! Huzzah! To execute all of these practices for every book you read would be exhausting and time-consuming. I know that my enjoyment would probably be lessened if I did this for everything I read. So, take a few points and apply them to your reading. Personally, I resolved to read the difficult books I encounter all the way through (not something I’ve always done in the past), and to keep a short journal of every book I read that answers, at least in part, the four questions above.

Why Read Analytically?

This can sound like a lot of work, and you may be asking yourself if analytical reading is really worthwhile. Isn’t reading something you do for pleasure and entertainment? Partially, yes. You certainly don’t need to be sketching out an outline while you’re reading Dan Brown’s Inferno on the beach this summer (although maybe doing so will help you solve the mystery before Langdon does).

As the late great Stephen Covey taught us, however, a man should always be “sharpening the saw.†This means keeping yourself sharp in all areas of your life. Doing any kind of reading is beneficial, but engaging in analytical reading from time to time can greatly enhance these benefits and help us become better men in several ways:

Increases your attention span. The internet has given us more reading opportunities than ever before. But oftentimes our cyber reading consists of skimming and/or quickly jumping from one thing to the next without giving each much thought at all. Have you ever tried to talk to someone about something you read on the net earlier in the day only to find you couldn’t really recall much about it? Reading a book analytically gives your focus and your skills for diving into a single thing deeply and mining it for all it’s worth some much needed training and exercise. It greatly sharpens your ability to handle something as a whole, rather than in part.

Enhances your critical thinking abilities. You can read, but how are you at examining something critically? Analytical reading hones your ability to evaluate truth, weigh evidence and sources, synthesize information, make connections between different things, evaluate claims, discover wisdom hidden below the surface, understand others’ motivations, interpret symbolism, and draw your own conclusions. Quite obviously these skills are not limited to helping you better enjoy books, but are absolutely vital in becoming an independent, perceptive, and well-informed citizen and man.

Shapes you into a better man. A man who sees personal growth as being something important to him will take time to meditate on life and consider the areas in which he can improve. Books facilitate this reflection in a unique way because they present us with characters or stories (be they real-life or fictional) that we can relate to in at least some small way.

As an example, I just finished the recent sci-fi hit, Wool. It’s a unique story with great characters, and the author is fast becoming a celebrity in the indie publishing world. I could have quite easily read it and moved on to the next book in the series. But to pause, and read through passages that I highlighted, and take even just 10 minutes considering what can be learned from the book gave me a greater reading experience. Wool forced me to ask myself if there are areas of improvement in my life that I’ve glanced over simply because it’s something I’ve always done. It forced me to ask about the ways in which I’ve lessened risk simply because it was the easier way to live. I learned that doing the right thing is often terribly uncomfortable. It’s not the first time I’ve learned that lesson, but seeing it again in a unique story gives me yet another chance to be reminded of the importance of that lesson.

Reading analytically offers valuable opportunities for this kind of needed reflection and can help you think through the kind of man you are, don’t want to be, and definitely hope to become.

Additional Reading Tidbits

- Consider paper vs. ebook. I was once a Kindle devotee. I still do a lot of reading on it, but I’ve moved to actually preferring paper. Even though you can scan all your Kindle notes and highlights at once, it’s actually easier to navigate a paper book, and skim it, in my opinion. There’s also something to be said about the reading experience. With digital devices, you really only get one sense involved — sight. With a physical book, you get multiple senses involved, making it a more immersive experience. You can feel the paper on your fingers as you turn the page, you can smell that new book (or old book) smell that is so distinct. What’s your preference? Has it changed?

- Consider new vs. used. This is just a personal thing, but I love used books in many cases. I appreciate just knowing that someone before me has enjoyed this very text. Especially when it’s an old book, it’s always fun to wonder how many people had their eyes on these words, and what kind of setting they were in. On an airplane in 1960? In a bar in the 80s? Perhaps in college just a few years ago?

- Consider your variety of fiction vs. non-fiction. There are significant benefits to reading a variety of genres. I am almost always reading one fiction and one non-fiction book at the same time. Your mind grows as you experience new things. Don’t pigeonhole yourself into thinking you only like one genre. I recently read some science fiction (something I didn’t think I liked very much) at the recommendation of a friend, and now I want to read much more. I’m hooked.

- Consider whether to take notes in the book itself. I love underlining great sentences and taking short notes in pencil of things that pop into my head as I read. The only time I don’t do this is when it’s a book I plan on either giving to a friend to read, or giving away to Goodwill or a used bookstore. Some people are quite opinionated about this one, so let’s hear your thoughts!

Keep up with all my reading and bookish ideas by subscribing to my weekly newsletter.

Tags: Books