Biographies are a particularly rich genre of books. By reading them you can learn not only about an individual’s life, but through that personal prism, find an accessible window to the historical period in which they lived. Paradoxically, the more particular something is, the more generally it can be applied, and even if some figure lived a very different and much more epic life than yours, following the contours of their story can grant you plenty of insight into your own.

But what do you do when you decide to read a biography of someone, and find there are multiple options to choose from?

There are said to be upwards of 15,000 books about Abraham Lincoln, the most of any figure in history outside of Jesus. Plenty of other figures have bibliographical files reaching into the thousands, and countless other persons of lesser historical importance have more than a few major biographies about them too. With numbers like that, selecting the best one to read can turn a simple quest for a book to read into a long-term research project. But there are a few methods you can use to sort through the options and find the right biography for you, which I’ll detail below.

Consider the Time Period and Publishing Date

If an individual was particularly eminent, a new biography about them is likely to come out every decade or two. You can find books on the same person published in 1920, 1970, and 2020, and each will give you a very different reading experience; for example, a biography of Thomas Jefferson from the 1950s paints a different picture of the man than does a biography of him from the last decade. All books, just like their subjects, are products of their time.

One of the main differences between older and newer biographies is the way they approach their subjects and how the author views what a biography is “forâ€:

Older Bios

Older biographies tend to concentrate more on a subject’s outward accomplishments than their inner thoughts and private life. They don’t get much into interpersonal relationships nor traffic in psychological speculation. Digging into an individual’s private life was formerly seen as inappropriate, and older biographies are written more like eulogies — summaries of the broader, publicly-known contours of a person’s life, with their failings downplayed, and their achievements emphasized, all tinged with a bit of romanticism and idealism.

In line with this, older biographies are sometimes trying to subtly or not so subtly offer a moral education along with an individual’s story, and are often written in a more inspiring, soul-stirring manner. For example, Robert Richardson’s 1986 biography of Thoreau is far more meaningful than anything new on the market. In general, the most transcendent biographies I’ve read — those that inflame my thumos — are on the older end. It’s a style of writing no longer in vogue, but still worth consuming.

Newer Bios

Newer biographies are written in a more journalistic style, in which the author’s aim is more to pass along information than to impart inspiration; as such, they tend to offer a more balanced, less mythical and romantic view of the past.

Modern biographies often contain updated, more accurate information about their subject, gleaned from declassified medical records, previously family-kept letters, and recently unearthed journals. Such sources are used to fill in details not only about a person’s public life, but to analyze their private life and psychology as well, all of which can really change how an individual is written about and viewed. Modern bios typically take a “warts-and-all†approach to their subjects, not shying away from pointing out a subject’s perceived shortcomings or moral failings, nor from speculating about potential skeletons in their closet. For example, even modern authors like Ron Chernow and Andrew Roberts, who take more of a heroic stance towards their subjects, will write about and address the poor treatment of George Washington’s slaves or Winston Churchill’s belief in the superiority of white, English-speaking people, respectively.

Beyond the difference in tone/approach between older and newer bios, you’ll also find a difference in writing style, with the style of the latter — which relies more on an accessible, narrative format than in decades past — being much easier to read. This newer style of biography isn’t necessarily superior to the drier, more linear style of the past, but it is often more palatable.

Which route you should go when there’s an older and a newer version of a biography available is up to your own tastes and aims with reading. Do you want to be informed? Do you want myths busted? Do you want to be inspired?

Read Multiple First Chapters

The best, easiest way to discern between various biographies on the same person is to simply read the first chapter of a number of books. Within a few pages, you’ll get a sense of the writing style and the author’s general thesis of the person.

Let’s look at the example of Napoleon through two of his recent biographers: When you read the introduction to Andrew Roberts’ biography of Napoleon, you’ll see that the author views the French general through a “Great Man†lens of history — that is, Napoleon was a misunderstood but brilliant and singular leader who changed the course of history through the exercise of admirable and heroic qualities. As mentioned, Roberts writes in a style that harkens back to the “moral†biographies of decades past but have recently gone out of vogue.

Adam Zamoyski, another biographer, has more of a “product of his times†view of Napoleon, and it becomes obvious right away in the preface that the author takes no moral stance towards the man, but simply seeks to explain him. Even looking at the covers, you can see that there’s going to be a difference in their posture towards their subject.

While I used to just read the introduction/preface to make my choices, I’ve recently discovered I should go just a little further and read the first actual chapter. In introductory text, some authors will use a different, more casual tone than they do in the “real†text, which can be a little misleading to a reader who’s trying to choose a book.

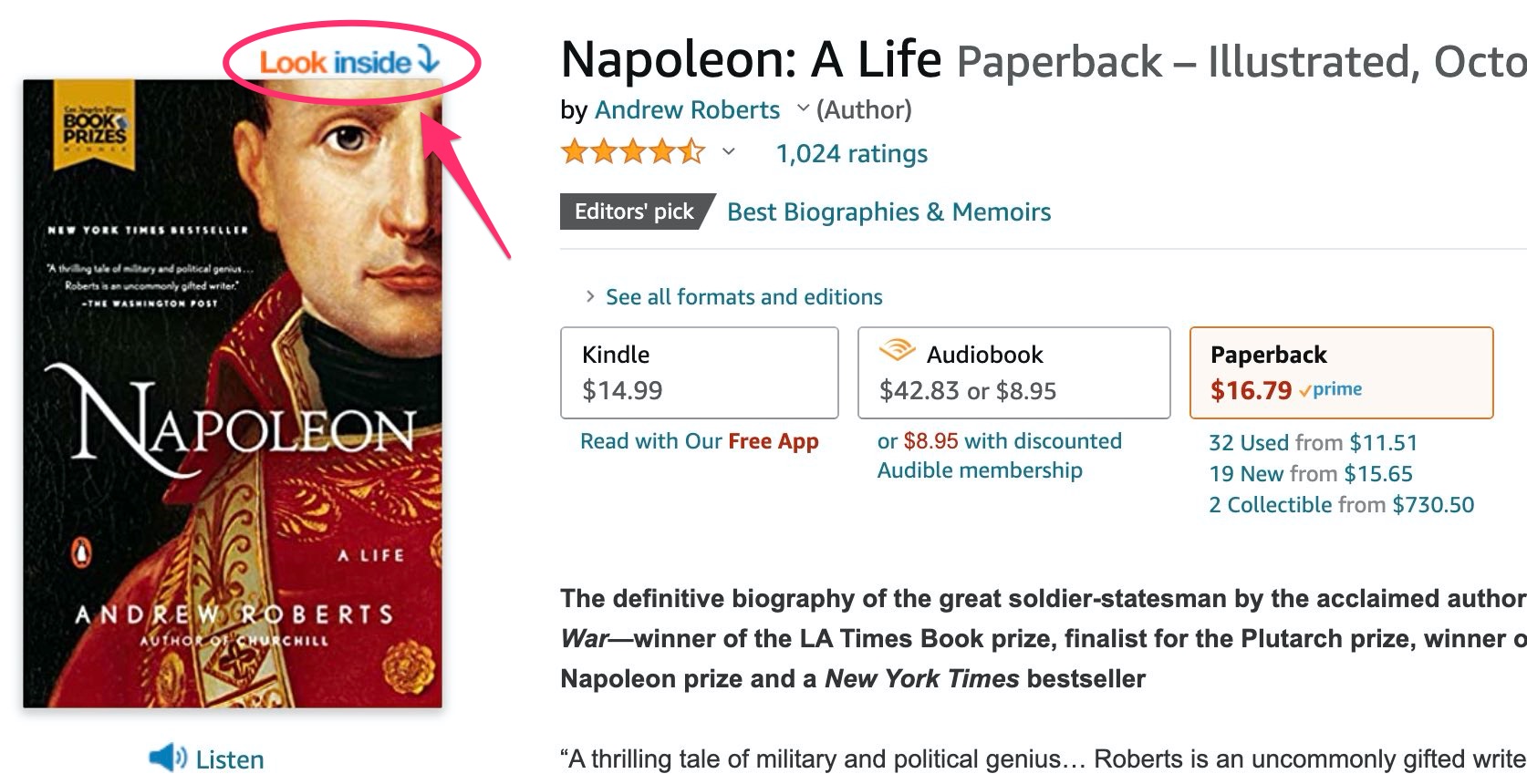

In a bookstore, this sort of comparative reading is an incredibly easy thing to do. Online, particularly with Amazon, you have a few options: 1) Take advantage of the free Kindle samples that Amazon dishes out. There’s no limit, so go crazy. 2) For newer and more popular titles, you can hit the “Look Inside†button on the paperback or hardcover options, and you can often read quite a few pages of the introduction, preface, and/or first chapter(s). 3) If it’s an older, less popular book, you might just have to buy some books and test ‘em out. Here’s a trick to keep in mind: as long as it’s fulfilled by Amazon (and not a third-party seller), you can return any book within 30 days. So grab a few Lincoln biographies, read the first chapter of each, and only keep the one you like best (or maybe you’ll realize you want to read a number of viewpoints!).

Read Reviews

Book reviews, both from average consumers and critics, should be taken into consideration. On Amazon, people are weird about reviews. They’ll get oddly personal or review just the product/packaging or leave a one-word summary of their thoughts (“Terrible!â€). I’ve found Goodreads to be a much more accurate review site because people posting there tend to be dedicated readers. You’re not going to use and post reviews to Goodreads if it’s not a somewhat passionate hobby.

When it comes to critics’ reviews, there are a few places I go. Kirkus Reviews and Publishers Weekly offer short, summary-like takes that are published without bylines in order to remove any semblance of bias. The other primary outlets I go to are The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. Both provide longer form, essay-like reviews that go more in-depth into a book’s strengths and weaknesses, but each can be politically/culturally slanted too. Reading both will provide a good balance.

Reviews shouldn’t be taken without a grain of salt, but if you’ve read a couple chapters of a book and enjoyed it, then gone on to find favorable reviews across the board, going with that particular biography will be a pretty safe bet.

Factor in Length and Time Commitment

As I’ve taught more — and particularly, as I’ve done more after-action evaluation on which books actually make a difference in the lives of students and friends — I’ve come to value more books and writers that economize well. . . . over time I’ve come to prefer Robert Dallek to Robert Caro for a biography of Lyndon Johnson. Both of them are brilliant, and Caro’s details are amazing, but there’s a lot more bang per paragraph in Dallek’s 400 pages than in Caro’s 3,000-plus-page version. —Senator Ben Sasse

When I first started reading biographies, I’d go full obsessive bibliophile and want to explore the longest series and thickest books I could find. I read Sasse’s philosophy on brevity when it was published a couple years ago and thought it was lame. But I gotta say, a couple years later and with dozens more biographies in my “books read†list, I agree with him more and more.

Life is a busy endeavor and motivation for a personal reading project can be hard to come by. Staring down a multi-volume biography can be so intimidating as to render you unable to even start. It’s perfectly acceptable to pick a shorter book that won’t take as much time, and as Sasse said, offers “more bang per paragraph.†Sometimes a book like that will spur your interest and lead you to further reading; sometimes, on the other hand, you’ll realize that a relatively bite-sized sampling is all you needed on a certain subject.

And don’t neglect what are often called “micro-histories†of certain individuals. These are books that delve into a single aspect of a subject or just a short period of time in their life rather than the entire cradle-to-grave treatment. These sorts of books can speak volumes to the essence of a person and give the reader an outsized impact without requiring the commitment of a door-stopping tome. When it comes to Grover Cleveland, for instance, I much preferred Matthew Algeo’s slim The President Is a Sick Man to the multiple 500+ page options. It also helped me realize that I don’t really care to know much more about Cleveland.

Read Authors You Know You Enjoy!

Once you find an author you really like, stick with ‘em! This is sort of an obvious point, and yet when it comes to choosing the next subject of my reading endeavors, I don’t factor it in often enough. Jean Edward Smith, for example, writes incredibly readable and insightful books that have been among my favorites in the biography category. What I haven’t done yet, but should, is take up his books on John Marshall and Lucius Clay—less sexy subjects—rather than dive into unknown authorial waters with more recognizable subjects. Ditto for other writers I admire, like Walter Isaacson, Ron Chernow, Robert Massie, etc.

Again, this is a tactic I’ve only half-heartedly put into practice thus far, but have been immensely rewarded by and plan on doing more of in the coming year.

For more reading tips and book recommendations, subscribe to my weekly newsletter.

Tags: Books