Fishing with a rod and line, and an artificial lightweight lure made to imitate fish prey — that is, fly fishing — was first recorded around the year 200. And while modern innovation has improved the quality and durability of the materials, the basics of the sport and pastime have remained largely the same. Attach a lure (or “flyâ€) to a line, cast it in the water, and see what happens.

Growing up, I fished in a boat with my uncle every now and then, but didn’t take it up on my own beyond that. Ever since moving to Colorado 5 years ago, though, I’ve been intrigued by fly fishing. You see fishermen in nearly every stream you pass by, and our family often encounters them on the trails we traverse. It seems like such an elegant way to pass the time and settle your mind, while also fulfilling the ancient role of Provider.

So over Labor Day, I finally decided to hire a guide and learn the ropes. Below, I’ll share those ropes with you: why you’d choose fly fishing over other methods, gear to look for, fly and casting basics, and finally some concrete tips on actually getting yourself started with this age-old pursuit. Keep in mind this is a guide for folks who have either never fly fished, or have only done so a small handful of times and with little knowledge. It’s for men who’ve wanted to get into fly fishing, but haven’t known where to begin.

If that’s you, I hope this guide can point you in the right direction.

Why Fly Fish? What Distinguishes It From Other Types of Fishing?

“To go fishing is the chance to wash one’s soul with pure air, with the rush of the brook, or with the shimmer of sun on blue water. It brings meekness and inspiration from the decency of nature, charity toward tackle-makers, patience toward fish, a mockery of profits and egos, a quieting of hate, a rejoicing that you do not have to decide a darned thing until next week. And it is discipline in the equality of men — for all men are equal before fish.” —Herbert Hoover, avid fly fishermen

While spin casting with a spinning reel is a great introduction to fishing, many anglers would argue fly fishing elevates this pastime into a real art.

Why is this? What are the differences?

When it comes to the practicalities, the differences are many. To name just a few, in fly fishing:

- the rods are lightweight and much longer

- the bait (or “flyâ€) is super lightweight, artificial, and meant to imitate food (rather than using live bait or heavy lures)

- the line itself is heavier, and is what provides the weight to cast, versus the bait or lure itself

- you’re typically fishing in moving water (and often in the water) vs. the still water of lakes

- you’re almost constantly in motion rather than just sitting on a boat waiting for a bobber to dip; your arms get a good workout

Beyond the practical differences, fly fishing is often labeled as the purer form. It requires craftsmanship and true skill to cast your line, the flies themselves are works of art, and as we’ll see, you become a true master of the environment. When I asked my guide why fly fish, he grinned like the answer was obvious and said, “Why wouldn’t you?â€

With spinning reel fishing, the goal is often a combination of relaxation and volume — catching as many fish as you can while having a nice outing on a boat or sitting in a chair on the shoreline. It’s just easier.

With fly fishing, it’s more of a challenge. Can you trick the fish into biting onto your fly/hook? Not only that, can you successfully get the fish hooked at the right moment, and tease it into your hands/net? Can you navigate the stream, and know exactly where to place (or “presentâ€) your fly, so the fish are most likely to bite?

All of this is why you see romantic stories (and even philosophy books!) about fly fishing; it’s just a more poetic and artful form of the sport.

Now that we know the “why,†let’s get more into the “how.â€

What Kind of Gear Do You Need?

While you don’t need everything pictured above when you’re first starting with fly fishing, this gives you a general overview of the kinds of things you’ll likely eventually acquire and take with you as you get more into it. For a full description of each item pictured, click here.

When you think of fishing, and especially getting started with it, you likely think of all the stuff you’ll need to be successful. When I first got to the fly fishing shop and my guide was walking through all the gear we’d be taking advantage of, I was a little bit intimidated. There were multiple types and weights of line used, a case full of flies (ranging in size from a pinky nail to finger-length), gel to coat and waterproof the fly, tools and cutters for knot-tying and knot-untangling, not to mention waders, vests, and other clothing essentials.

I think my guide saw my wide eyes, because he then said, “Really, you don’t need this much stuff to start. Grab a pole, some line, and some flies, throw it in the water, and see what happens.†He then told me the story of a kid in town he knew who would tie some line to a stick, tie on a fly, and drop it in the water — and he’d catch some fish to boot. Like with anything, when you embrace fly fishing you’ll likely end up with plenty of specialized gear, but you don’t need all that when you’re first starting out.

Flies

Fly fishing gets its name from the bait that is used: artificial “flies†made to imitate what the fish are eating — bugs usually (like various types of . . . you guessed it, flies!), but sometimes even small rodents and other creatures.

There are numerous types and sizes of flies — dry flies, nymphs, streamers — and what you use will depend on the fish you’re trying to catch and your setting. If the fish aren’t biting, you’ll often change out a fly and try to intuit what they might be after that day or season. This is why fly fishermen are often amateur ichthyologists (fish scientists) and entomologists (insect scientists). They know types of fish, what those fish eat in what season, what the bugs look like at different times of the year, etc. My guide’s biological knowledge after years of fishing was truly astounding.

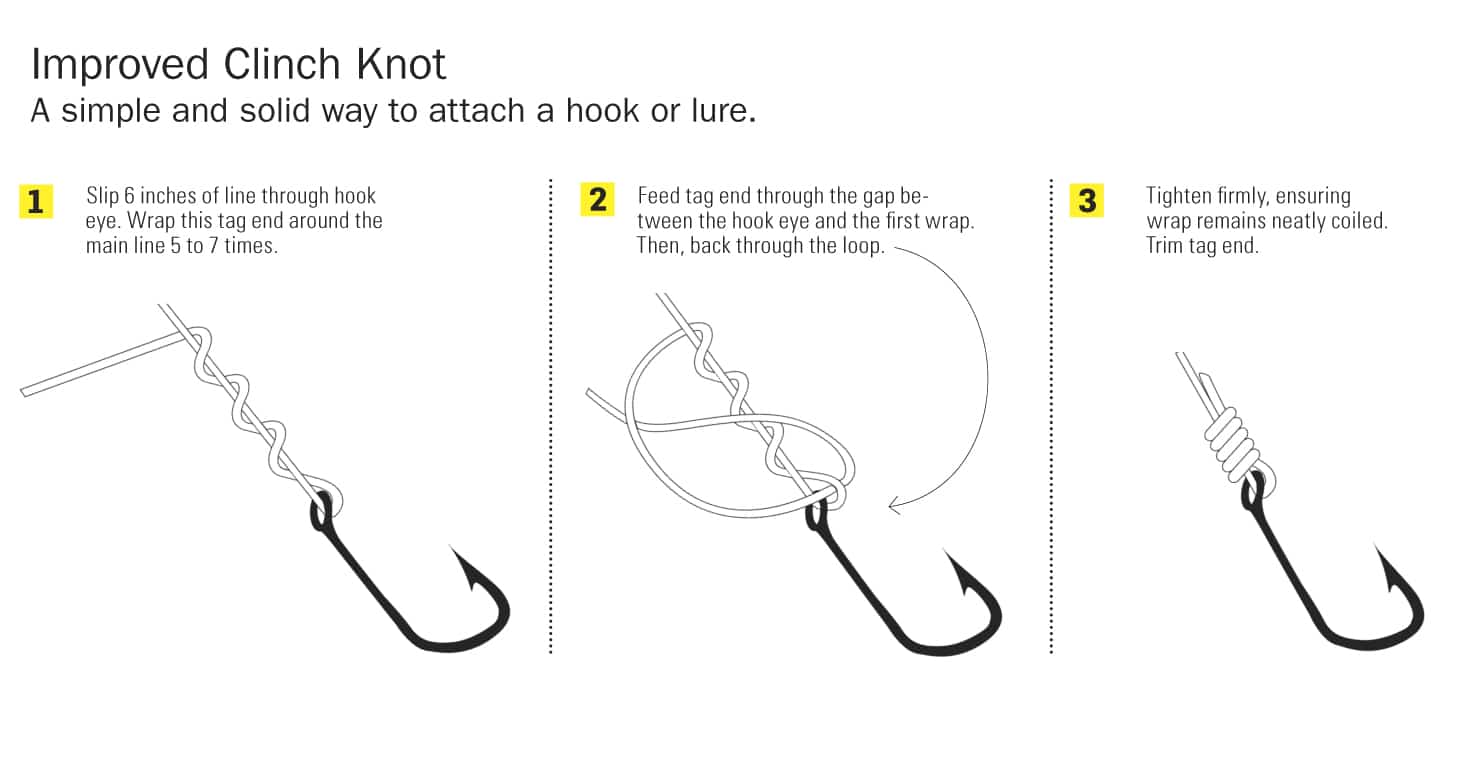

Once you can determine the right fly to use, there are a couple different acceptable knots for attaching that fly to your line, but the “improved clinch knot†seems to a favorite among a lot of experts. Check out this guide to not only that knot, but a handful of others used in fly fishing as well.

A great closeup of a homemade fly. You can see the colored thread carefully wrapped about the hook, with feathers and hairs attached to create that bug-like look.

Once you explore fly fishing, you’ll likely hear about folks who are “fly tying.†This is not a term for tying your fly to your line (as I initially and very naively thought), but rather a term for making your own flies rather than buying them. You’d do this to possibly save money (flies are easy to lose in trees or to rowdy fish), but also for the art of it. Flies truly are works of art, created with various materials like beads, foams, animal hairs, and much more. The beginner angler will not be fly tying; there are literally books written on the craft, and it requires a whole other set of tools and skills. This is something to look into after you’ve gotten the hang of the fishing itself.

Casting and Catching

The GIF above is from an Orvis instructional video. They have dozens of fly fishing videos for you to peruse.

Once you have your gear and fly all set, it’s time to cast. When you watch seasoned fly fishermen in action on the stream, it’s like seeing art in motion. The way the arm moves, followed by the line and fly, so delicately placed on the water exactly where it’s wanted. Let me tell ya, that’s not what it looks like for the rank beginner.

So here’s the scoop on fly casting: find someone to teach you. That’s truly the key. I could try to describe in text and illustrations how it happens, but that’s just not going to work. For this article, I actually researched the viability of putting together an illustrated guide on casting. But when I saw other guides that were out there and folks trying to describe it, I actually got more confused than when I was with my guide and trying it out with a rod in hand.

There are too many types of casting, too many subtle motions and arm movements, and too many ways to make mistakes for me to try to relate that all to you here on a website. Of all the projects and skills I’ve written about for the Art of Manliness, this is the one that most needs to be learned in the flesh, either from a friend or family member who fishes, or from an expert who you’ve paid to help guide you along.

The same goes for hooking and ultimately catching the fish. There’s a whole terminology that goes into casting and catching:

- Presentation

- Monofilament

- Strike

- Indicator

- Setting the hook

- Leader

- Tippet

- Riffle

And this is just a small sample. You don’t want to be wading into those waters on your own — literally or metaphorically.

So, how does the beginner actually go about getting started? Let’s take a look at that next.

Tips for Getting Started: A Linear Progression

Take a class. Chances are high that no matter where you live, some outfitter is offering a class on fly fishing. Be it a sporting goods store, a dedicated fly fishing shop, or even a community college, there are a lot of places putting on free (or low-cost) classes to learn the art. Orvis is a great place to look — they offer free classes in 42 states. They tend to start with a lecture portion on what I’ve covered above (but more in-depth), followed by hands-on instruction about lines, knots, flies, and casting. Depending on the shop, they’ll also have next-level classes, which sometimes include practicing in a stocked pond.

Casting a line into the East River near Crested Butte, CO. I had a great experience with Almont Anglers; give ’em a shout if you’re in the area!

Hire a guide. After you’ve taken a class or two, hire yourself a guide to take you on a half-day or full-day outing on the water. (If, that is, you don’t have an experienced friend or family member willing to take you and show you the ropes.) You can only learn so much in a classroom setting, even if there is some hands-on instruction involved. There’s nothing like being in the stream and seeing what a seasoned vet does in regards to which flies to use, where to cast, how he troubleshoots things, etc.

I would recommend going in that order of taking a class first before hiring a guide. I did not do that, and about half of our half-day together was spent teaching me the ropes and practicing in a pond, which likely could have all been accomplished beforehand.

A guide can be expensive — look to spend $150-$500 depending on your location, and whether you’re doing a full-day or half-day outing. Makes for a great gift to save up for if that’s a little out of reach.

Practice tying your knots and casting. While not on the water, you can practice a few things at home. First, work on your knots; lines and flies (which are often tiny) need tying together, and it’s only with plenty of practice that you can do so deftly and efficiently. My guide could rig up a fly in less than 30 seconds, while I was fumbling with what felt like sausage fingers for a couple minutes before getting it just right. That doesn’t seem like much time, but when you’re out in the river, it adds up. Plus, if you’re fumbling with your fly in the water, dropping it means losing a couple bucks right then and there.

Along with the guide listed above in the “Flies” section, Orvis also has a good encyclopedia of knots that one might use while fly fishing. (They truly are a gold mine of fly fishing info and instruction.)

You can also practice casting at home, though it’s admittedly a little tougher because you need adequate room to do it. If your driveway or backyard is long enough, start there. If you don’t have room at home, go to a large park, or even a lake to practice your casting, with actual fishing being a secondary pursuit to your practice efforts.

Start in lakes. While fly fishing is generally pictured as taking place in streams, plenty of fishermen practice their craft in lakes. Especially here in Colorado, it’s rather common to see guys (and gals) wading into cold mountain lakes. For the beginner, that’s going to be the easier route to go for one main reason: it’s just easier to keep an eye on your fly when the water is still.

When fly fishing, there’s no bobber or super obvious jump on the line to cue you into a fish being hooked. Rather, you have to carefully watch your fly and line, and tug up when you see or feel slight movement in order to hook the fish (called “setting the hookâ€). In a flowing river or creek, when your fly and line is drifting and undulating with the current, it’s really hard to tell if that gentle tug on the line is a fish, or just a rock, or even the tug of the water itself. Start in lakes to really get the hang of things.

Prepare to practice. A lot. I asked my guide about how long it took him to really master all this stuff, and he said it happens in phases. First you get good at casting and tying your knots, then you get good at noticing when a fish has shown interest in your fly, then you get good at setting the hook, then you get good at successfully reeling in and nabbing your fish, and finally once you have all that stuff taken care of, you can pay attention to the science of the fish and bugs, and know how to read the water and your environs. So, be prepared to try a lot, and fail a lot, before getting to a point of truly being comfortable in the water.