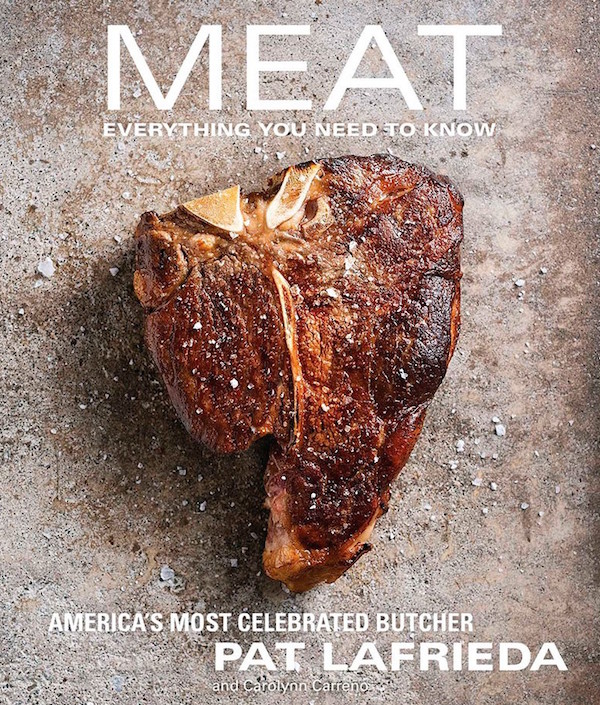

While meat makes up a big portion of Americans’ diet, few people know very much about how meat is sourced and butchered for consumption. Today on the show, I talk to a world-renowned third-generation butcher, Pat LaFrieda, about all things meat, including his new book, Meat: Everything You Need to Know. We begin our conversation talking about his family business in New York City and how it became one of the premier meatpackers in America. Pat then walks us through how that steak you’re grilling got there and all the factors that determine the price of meat.

We then shift from the macro to the micro of meat by discussing the tools Pat recommends every backyard chef should own, how to tell if meat is bad, and what dry aging does to beef. He then shares what his favorite cuts of beef, lamb, and pork are, how to cook them, and why he thinks you should be leery when a restaurant boasts about their delicious sirloin steaks.

Show Highlights

- How Pat got into butchering at a very young age

- How Pat’s company survived a downturn in the industry in the 90s

- The difference between cow and steer

- The business life of a butcher, and how prices get set

- What tools should every backyard chef have on hand?

- Why should people avoid frozen meat?

- Why Pat ages meat, and what happens in the cut during aging

- Can people age steak at home?

- How do you know when meat has gone bad?

- What’s the most underrated cut of beef?

- And the most overrated?

- What’s with NYC steakhouses serving thick slabs of bacon with their steak?

- The best pork cut

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Let’s Hear It for the Cheap Meats!

- How to Cook Pork Butt

- The Reverse Sear: The Best Method for Cooking Steak

- Podcast: Becoming a Backyard Pitmaster

- How to Make Prime Rib

- How to Light a Charcoal Grill

- How to Make Your Own Bacon

- Primal Cooking: Roasting Meat on a Spit

- How to Properly Sear a Steak

- How to Cook Steak on a Shovel

Meat has become a family favorite here in the McKay household. My kids like looking at the cross sections of the butchered animals so they can see what part of an animal is the source of the meat they eat. It’s also filled with fantastic recipes.

Connect With Pat

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Art of Charm Podcast. One of the few podcasts I listen to when not recording my own. Check out all they have to offer at www.artofcharm.com. Don’t miss one of their recent episodes with Paul Bloom about why empathy is actually overrated.

Saxx Underwear. Everything you didn’t know you needed in a pair of underwear. Get 20% off your first purchase by visiting SaxxUnderwear.com/manliness.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. While meat makes up a big portion of Americans’ diet, few people know very much about how meat is sourced and butchered for consumption. Today on the show, I talk to a world-renowned third-generation butcher, Pat LaFrieda, about all things meat. We begin our conversation talking about his family business in New York City and how it became one of the premier meat packers in America. Pat walks us through how the steak you’re grilling got there, and all the factors that determine the price of meat. We get very macro with butchering.

We then shift from the macro to the micro of meat by discussing the tools Pat recommends every backyard chef should own, how to tell if meat is bad, and what dry aging does to beef and whether you can do it on your own at your house. He then shares what his favorite cuts of beef, lamb, and pork are, how to cook them, and why he thinks you should be leery when a restaurant boasts about their delicious sirloin steaks. Really fascinating show, a lot of independence tidbits. After the shows over, check out the show notes at awin.is/butcher.

Pat LaFrieda. Welcome to the show.

Pat LaFrieda: Thank you for having me.

Brett McKay: You are a world famous butcher. You’re just coming out with a new book called, Meat. I love it. My kids love the books. They love looking at the cut out’s of the different animals, of the cow, the cross section.

Pat LaFrieda: Yeah, you don’t see it often. You really don’t. Usually, when you Google a cut of meat, you’re usually directed to a photograph that looks like a cartoon of an animal to a general area. I really thought it was important to segment each cut exactly where it lies in the animal.

Brett McKay: Yeah. My kids love it, cause now whenever we eat a hamburger, or a steak, they know what part of the cow it comes from.

Pat LaFrieda: That’s great.

Brett McKay: It’s been fun. Well, before we get to the book and talking about meat in general, let’s talk about your history, background. It’s really interesting. You’re the owner of a famous meat fulfillment company. You’re not a butcher for the average consumer. You actually give meat. You provide meat for all the big restaurants, steak houses in New York City. How did that happen? How’d you get started with that?

Pat LaFrieda: Well, I represent the third generation. I’m also Pat LaFrieda, the third. My dad took over from his father. My dad didn’t have a choice. He was to be in the meat business, and that’s just the way that generation was. My grandfather’s generation wanted their son to carry on their business. My dad, he wanted to opposite. He sent me to private school, off to college, and wanted me to go off and do something bigger and better.

The problem was, that in order to teach me work ethic, he would take me to work, since I’m 10 years old. I loved the business. I loved being the helper on the truck and getting to go down and speak to the chefs, and just knowing what happens in the kitchen. It’s amazing. If you can imagine the perspective of a child going into a kitchen and all the wild things that happen in a kitchen, for a kitchen to work.

When I graduated, with finance degree from college, I got a job on wall street almost immediately. I got my Series 7 in 63, which made me a licensed broker. I could not stand doing that for a living. I begged my dad to come into the family business. He told me, “No. No reason for you to come here. It’s not why I sent you off to get educated.” It was a little bit of a family bout. My aunt had come to my defense and she had run the business with my dad, and was retiring. She was a very tough lady, may she rest in peace. Her name was Lisa LaFrieda. She convinced my dad to let me join the company.

We were very small. We only had two vans that made deliveries. My father, essentially was the head butcher, and had an assistant. They had 44 customers. I would go to work at 3am. I would work with my dad, cutting meat like I knew and was trained to do, and slowly grew the business by running up to a shower, changing into a suit after the meat was cut and the driver left, to make his deliveries. I would walk into restaurants and actually get new accounts, and we grew the business really organically. A grass roots in that regard.

Brett McKay: Yeah. What’s crazy, during the 80’s and like early 90’s … This is when the meatpacking industry in New York City saw a downturn. What do you think helped Pat LaFrieda meat purveyors thrive, not only survive, but thrive during that time, to become this big Juggernaut that you are today?

Pat LaFrieda: Well, I’ll tell you, I joined my dad in 94. When his dad passed away in 89, I could see my dad did not have interest in growing the business anymore. I think it’s part of the reason he didn’t want me to join the business. That was for their generation, and the generation before my dad’s. If you had a meat company in the meatpacking district, there are almost none of those companies that owned their own building, so they were all renting.

Some of these leases were 20 or 30 year leases. There came a time when the meat market became a discovered secret treasure. The real estate values went so high, that if you didn’t own your own building, when your lease was up, you were done, because you couldn’t go from 40 dollars a square foot to a thousand dollars a square foot. You just could not … There’s not that kind of return and net profit in this industry.

My dad always wanted to buy his own property and control his own destiny. The fact of his genius of finding a location down in that area and purchasing it, when those rents did go up very quickly to unaffordable numbers, here I wasn’t in a company protected by the ownership of the building. That was a massive, massive key component to us surviving that period. Art galleries and restaurants, where raw meat used to be hanging, is something that no one envisioned, that was in our industry. My dad did.

Brett McKay: Wow. You mentioned earlier, you know, your day, when you were working with your dad would start at 3 o’clock in the morning. How late would you sometimes work to?

Pat LaFrieda: Oh, we would often be done around 5pm.

Brett McKay: Wow. And I imagine the work is pretty physical?

Pat LaFrieda: Very physical and you have to be able to work in a refrigerator. For anyone that’s never felt that before, 35 degrees, 36 degrees, you know, your entire work day, it does take something, like experience to get acclimated to. I find the largest turnover rate with new employees, is within the first two days. If they can last the first two days, they understand that, okay. Once they get moving and working, I’m gonna warm up. Before you know it, you’re gonna strip a layer or two off, before the end of the day. That fear that … It’s not talked about very often, but there is a fear in someone that gets put into a work environment that’s refrigerated. You have to get over that fear and realize, “Okay, this is normal. This is okay.”

Brett McKay: How does butchering work? Obviously meat comes from cows. Let’s talk about cow as a good example. Do they …

Pat LaFrieda: No, let’s talk about steer.

Brett McKay: Steer. Yes. Steer.

Pat LaFrieda: Well, let’s talk about the difference. The biggest, I think misconception that the general public has, is everyone thinks that beef is cow. Where cow is a female milking cow, is in the dairy industry. Cow meat does exist, but we have opted out of that, with the USDA. Our company doesn’t handle any cow meat. The difference is in the age. Anything that’s over 30 months of age, we don’t touch. There’s a reason for that.

The 30 months of age, or more, can potentially have BSE, which is mad cow disease. It’s never been detected in anything less than 30 months of age. That’s where we get steer. The steer that we use, are on average, 22 to 24 months of age. That’s the difference. When a cow is in its eight year of giving milk, that’s usually about when they’ll send it to be harvested, because that meat has a place in the marketplace as well. It’s just gonna be the lowest form of meat, because it’s older, it’s tougher, it doesn’t taste as good as steer do at 24 months of age.

Brett McKay: So, we’re talking about steer. How does the steer come to you? What do you do with it after that point?

Pat LaFrieda: When I first started we were still using hanging meat on rails and kind of like, the movie Rocky, where Rocky was punching the meat, and it was hanging from a hook. That has changed in my generation. That is a good change, because meat that can fall and hurt someone, just to take that danger out of the scenario, was a great thing. The beef industry has changed in such a way, where it actually follows the most capitalist example possible, in a good way.

What I mean by that is, in my dad’s generation, if he wanted to sell two whole strip loins, that would yield about, let’s say 24 steaks. He would also have to sell the rest of the animal. Where do you sell the whole inside round, bottom round, beef eye round, the chuck, the neck. You have to sell all of those parts and have no waste, because it’d be a sin to have waste to begin with. You wouldn’t be profitable at all.

Farmers actually have to, even take into consideration what the hide would be worth and what is worth in the leather industry at that time. How it’s changed is that meat, at the processing facilities in the country, is broken down into the different cuts and equations get formed. If there’s a huge demand for rib eye, a price will be set for it, at a high price, and that would lower the price of everything, every other cut in the animal. It would go by demand, each week it changes obviously, but that’s the way pricing structure works. I only need to bring in the cuts of meat that I need, that’s vastly different from a generation before me, where my dad would never be able to grow the business in fine dining like we have. We would have had to get rid of the rest of the animal.

For example, inside rounds make great roast beefs. It’s the muscle that we are all sitting on right now. Roasting that, that should really go to someone who’s processing roast beefs, whereas, I need more of the middle meats, the strip loins, the rib eyes, where we get cowboy steaks and Tomahawks. I need more of that meat, and the only reason I’m able to get it is because the person who wants the inside rounds is able to get that delivered to them only. They would have no use for the steaks that I would have use for. It’s become a very sustainable and more importantly, more efficient system than my dad’s generation.

Brett McKay: Does the same apply to pork, or lamb, the same sort of thing, where you only get the cuts you just need?

Pat LaFrieda: Yes. It does apply to lamb, pork, veal, just like it does in beef, but you’ll find that most people eat beef or poultry and then less, lamb, pork, and so on and so. You’ll get more efficiency in the beef industry, than you would the pork industry, when it comes to being able to buy individual cuts.

Brett McKay: How is what you do, different from say, with the neighborhood, the corner butcher does, right? You guys don’t serve individual consumers. Your guys more focused on restaurants.

Pat LaFrieda: Well yeah, our entire history was based on selling restaurants. Now, an amazing supermarket chain, ShopRite, did approach us last year, and they were big fans of our product in restaurants and wanted to see how it would work on their retail shelf, because what a retailer would normally carry is different from what we do. Dry aged prime steaks is not something you’d normally find. They were shocked. They actually had three times the demand for our products than, what their most optimistic forecaster saw in what our success would be in the general public.

Specializing in the top 10% of what’s produced in our country, has really given us an edge in that. Having beef procurement people on the ground, speaking to the growers, who are the farmers, about exactly how we want, and what we want our beef to be, as far as raising protocols and finishing protocols, that’s taking it almost to the point of being vertical.

We wouldn’t want to be vertical in our situation, because if there’s bad weather in one part of the country, and very little beef came from that part, we would be out of business. Having the ability to spread across the corn belt and to work with different farmers, in multiple states, and then getting the top 10% of product that comes from those growers, is really the key to our success.

That did not take over nigh to happen. It took many years of what’s very important. I think it’s probably true in any industry, is we made sure we paid our bills, before we ate. My father could not sleep, if he thought he owed someone money. If you’re willing to pay someone … That’s a huge problem in our industry. I have an entire floor of personnel, and all they do is try to keep our restaurant customers current and it’s not easy for the restaurants to do so, but we work with them a lot.

As a restaurant may get 30 days of credit from me, I have to pay the growers within seven days. That’s seven days from once it leaves the facility in which it was harvested. I don’t get it for about four days after that. It’s on the road, in a refrigerated truck. Three days after I get the product, the products paid for, and I still have to sell it and then collect the money for it.

Regardless if I’ve collected or not, I have to pay my taxes as if I did collect the money, which is very, very difficult. We’ve had our times when, we have to go back and use our own personal money. It’s been quite some time, since that’s happened. If you’re not careful … You have to pay your taxes. Something that we also take very seriously.

If your restaurants get too far out on you, and there’s too much in receivables, then you won’t be able to pay your meat bill in seven days. The farmer doesn’t want to hear from you. That’s it. You get blacklisted in that industry, you’re done. It’s something that we worked very hard, and always thought about, is that we need to make sure we pay for our product and make sure our farmers get paid before we eat. It’s very simply said in my family.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I imagine it’s a tough business too, because weather can affect price. A few years ago, when there was some drought in Texas, and Oklahoma, the price for leather and for beef went up dramatically cause all the cows were dying.

Pat LaFrieda: Yes. They were-

Brett McKay: I meant steers. I said cows again.

Pat LaFrieda: In those years, there was an amazing amount of corn production. That’s what kept beef affordable, is that finishing them off on corn, that’s inexpensive, even through those droughts, corn production was great. You could see it more in poultry. Poultry right now costs a little bit less than when I started with my dad in 1994, full-time, which I think is remarkable.

I think it’s what kept food pricing and the inflation of food pricing where it is. We all see the difference in what our grocery bill is, right? I think the one thing that has kept it, even affordable, is the availability of corn in our country, plays a huge role in the industry, and in pricing.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk a bit about your book and some of the tips you’re providing. What I love about it, you look at each type of meat. You’ve got beef, pork, lamb. You have veal. Not only do you talk about the different cuts, which I find extremely useful, but you also provide some recipes. Let’s sort of talk big picture here. I know a lot of guys listen to podcasts. They like to cook outdoors, grill, and particularly they’re probably grilling meat of some sort. What tools do you recommend that people have on hand for all their meat preparation and meat cooking needs?

Pat LaFrieda: I would say as a butcher … People love to show me their knife set. It’s kind of comical. As a guest, over anyone’s house, like, “Hey Pat. Look at these knives I bought from this maker.” As I look through them, none of them are meat knives. To have a knife, which we call a boning knife that de-bones, let’s say a leg of lamb, or a rib of beef, to a longer scimitar knife, to cut slices off of a whole strip, or to cut beef into maybe stew. Its important. They’re very different from a chefs knife, or a pairing knife, or something that’s made for produce. That’s the first key tool you need.

The biggest issue I see in grilling is when you have a grill that is not able to get to the temperature in which you want. That’s a big debate. What’s better, natural gas or charcoal? Of course charcoal tastes better. If you have the hours that I do, which translates into very little amount of time that you have to barbecue. I need gas. I gotta cook with gas. I gotta get that grill up as high as I can, as fast as I can. I don’t have time to play with charcoal every time I grill. If I did, I wouldn’t be able to grill anywhere near as much as I do. I think having a grill that’s able to reach the temperature that you want in the timeframe that you want.

Recently I found a grill … I almost didn’t even look at it. It’s the size of a toaster, and kind of looks like a toaster without the door. It’s made in Germany. It’s made by Otto Wild. Restaurants would call it a salamander, or a cheese melt, where the heat’s only coming from above. It has this great tray underneath that you put a little water in first, so that you never get a flare up. There’s no fire ever, if you are cooking a great quality cut of meat, it mostly has a lot of intramuscular fat, so that’s the marbling you see. It’s going to lose some of that fat in the cooking process, and leave behind a great tasting steak.

To be able to do it in a manner where you don’t have this huge flaring up, when you’re trying to get a sear on meat, is very important. Otherwise, what you get is the steam effect. You get that gray steak, that’s gray throughout, because you tried to get some color on it, but by the time that happened the heat was able to transfer through the steak all the way through and to cook it all the way through. The least desirable for a butcher to eat a cut of meat like that.

Brett McKay: Gotcha. So, good knives, some meat knives, and then a grill that can get you the right heat …

Pat LaFrieda: Right.

Brett McKay: …are the big essential things. All right, well let’s talk about some of the things you hear about meat. You talk about this. Why should people avoid frozen meat? What happens to meat whenever you freeze it and then thaw it and then cook it?

Pat LaFrieda: Well, if you know where the source of meat is, there’s nothing wrong with freezing meat. I don’t like frozen meat, because traceability. It all depends. If you’re to buy frozen meat, why would anyone want to buy frozen meat, when meat is readily available in America seven days a week?

The reason that I don’t like frozen meat in that regard is, because when you freeze meat and then defrost it, you’ll notice so much more purge, some much more of the natural juices are escaping and they’re in that package when you defrost it. Frozen meat, it’s very questionable as to traceability, where it’s from. And then it does lose some quality. If it didn’t, my life would be a lot easier, because everything we make, we would make it ahead of time, and freeze it and ship it. It’s just not the way it is.

The fresher the meat is cut, to include dry aged meat, so now we’re talking about aged meat, that’s been aging for 45 days. If that’s portioned and then eaten within a few days, that’s the best steak you’re ever gonna eat. If you were to take that meat and freeze it, and defrost it, and then cook it, you lose a lot of the great qualities of what was preserved. That’s just natural in the freezing process.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about aged meat. What are you doing there? What does aging beef do and why does it taste so much better than just cooking it when it’s fresh?

Pat LaFrieda: Dry aging beef is really controlled decomposition of the meat. We are making sure that the meat does not get rotten as it would normally in 60 days, or 120 days is the max that go, by making sure that the variables in the room are correct. That’s wind circulation, that’s temperature, and that is the humidity, keeping the humidity down in the room. What we’re doing is letting the collagen that holds the muscle fiber together, really break down and what it’s leaving behind is something that’s got a lot more flavor than when it was fresh.

It’s kind of like, trying to pick up a water balloon, with two fingers. You can do it with a dry aged steak. A fresh steak would be more like the water balloon, where it’s dropping down. Very much like you would, broccoli rabe is a good example in produce, where we’re trying to get the moisture out, so we kind of put it in a saute pan, with some olive oil and cook it for a while.

What we’re doing in the dry aging process, is making a lot of that water come out of the muscle group and there’s plenty that we have to shave off, when we’re ready to portion that product. Anything on the exterior is removed. What’s left behind is an enhanced beef flavor that is so much more tender, I should say, and so much more flavorful than when it was fresh.

Brett McKay: Gotcha. Is this something that people could do at home, or does it require a lot of fine tuning, and using special equipment to get the right conditions till it ages properly?

Pat LaFrieda: It’s a great question. It’s almost impossible to do at home, unless you have a refrigerator that was dedicated to that, and one in which you could read the internal temperature of the refrigerator, and the humidity. The humidity’s got to be controlled. We have several system that take the moisture out of the air. It’s very difficult to do at home, it’s nearly impossible to get it right, unless you have a very small amount in the refrigerator and you were able to read the environment.

I’ll tell you, what you would normally get, if you tried to do it at home in a refrigerator, because a refrigerator is a natural dehumidifier. Any refrigerator has water that it expels. That water is expelling is from inside, the moisture that’s inside the air, that gets on the coils, and gets drained out, or in some refrigerators, it is evaporated off the top. It’s still not enough to keep up with the amount of water that’s in the muscle of a whole loin, let’s say. It’s not worth your time. You can make prosciutto’s at home. That’s something that’s controllable. Dry aged meat, more times than not, it would rot on anyone trying to do it.

Brett McKay: Speaking of rot, like, how do you know when meat is bad? There have been instances where I have meat. It’s been in my fridge for a few days, and like, it’s kind of turning gray, and I’m like, “Is this still edible?” I throw it out. Sometimes I think, “Well, maybe I shouldn’t have thrown that out, it was actually good.” Is there any tell tale signs that you’ve got some rotten meat and you shouldn’t consume it?

Pat LaFrieda: Ugh yeah. I laughed at what you were describing. I know exactly what you mean. The best way to see if meat is still good, because … The turning gray is not a problem. That’s oxidation. It’s gong to happen. If you were to make fresh ground beef right now and form it into a patty, and put it in your fridge, the next day if you were to break it open, in the middle, it would be turning a darker brown and you would wonder, “Wait. Is this still good?” And then would eventually turn to a grayish color. All of that is fine. That has to do with the oxygen and oxidation.

The best way to tell if meat is good or not, by it not being a bright-ish green color, which is obvious, right? Beyond that, smelling the meat. If the meat smells good, most likely it is good. I myself, as a butcher have taken steaks home and put them in the fridge, then you’re like, “Oh. I forgot I had those steaks in the fridge,” five days later. Well, all you have to do is open the package and smell the meat. If the meat still smells good, it’s good. No one really explains it like that. That is the best way to tell.

Brett McKay: As a butcher, you’re a professional here. What do you think is the most underrated cut of beef?

Pat LaFrieda: The most underrated. Probably flat irons, especially for the price. Flat Iron’s are from the front shoulder. They’re from the clod, and more specifically from the top blade steak, is exactly where it is. Blindfolded, it tastes the same as a New York strip steak. It’s about 25% of the cost, of a New York strip, but you wouldn’t be able to tell the difference between the two. The striation in the muscle is the same, the marbleization is the same, and the flavor is the same. When you find this, you know, cuts of meat like that, that have a New York strip steak experience, at 25% the cost, it’s a great economy cut.

Brett McKay: You now, what’s crazy are these economy cuts though. Sometimes they get really popular and then they’re more expensive. That happened with flank steak, I feel like, a few years ago.

Pat LaFrieda: For a little while it happened with hanger steak. I mean, hanger steak came back. Hanger steak is the butcher steak, because it’s the only muscle in the entire animals that you need to remove, before you split the animal. On the assembly line, as the animal is eviscerated and the hide is removed, it’s then split. You have to pump the brakes for a second and remove by opening up the actual cavity, because the hanger steak is on the inside, and it hangs from where the kidneys are. You need to remove it first, before you split the animal, or you’ll damage it.

It’s not symmetrical, like every other muscle in the animal, or in any mammal. The hanger steak if about 2/3rds as big on one side and the other third on the opposite side. That was a steak that was not easily marketable by a butcher, because they never thought of taking it out first, so when you got it, it was after the animal was split, and it didn’t really look much. You couldn’t make many portions, enough to sell to one restaurant to put on a menu. It had a lot of flavor, and butchers would then take it home, or throw it into the ground beef mix. One or the other.

When it was discovered how much flavor it had, and the breakers would start to remove it before and they were able to get enough of them to sell to someone like myself, who could then portion them into usable steaks, they became very popular, and doubled in price for a while. They’ve since come down a little bit, but that’s an example of economy cut that got more expensive than I would say, something comparable to it.

Brett McKay: Right. So, flat iron steak, most underrated. What do you think is the most overrated cut of beef?

Pat LaFrieda: The most overrated cut, I think is anything that’s referred to as sirloin. Nobody knows what the heck sirloin is. You know, you’ll put a TV on and there’s that commercial for surf and turf and it’s some sort of seafood and a sirloin steak. Oh boy. Oh boy. No one knows what the heck sirloin is.

Sirloin steak does not have much flavor at all. It’s part of the love handle of a steer. It comes from the top butt, the peeled knuckle, or the flap meat. One of those three muscle groups. Anything cut out of one of those three muscle groups, is considered sirloin. Retail butchers seem to throw that word around a lot and that’s why I think it’s the most overrated, because real sirloin steak is not much of a steak at all.

Brett McKay: Gotcha. Okay, I’ll remember that next time I go out to eat.

Pat LaFrieda: Don’t confuse that with strip loin.

Brett McKay: Okay.

Pat LaFrieda: Strip loin steak, very different from sirloin steak. Strip loin is a New York strip, from the back.

Brett McKay: What is, sort of the characteristics of a New York strip?

Pat LaFrieda: That’s the classic steak that’s the L part of the T-bone. That’s the steak on that side, so that’s from the back. There’s a finite amount of them per animal and that’s where I said earlier, about 24 steaks for those two strip loin pieces. It’s one of the more expensive cuts and center cut strip loin has no … They call them vein steaks, but it’s really a nerve that runs through. Got no vein, or nerve that runs through any part of the steak, so that you have this great steak experience. When you eat the best steak of your life, it’ll most likely be a rib eye, or a strip loin that’s been aged and is prime and domestic.

Brett McKay: Maybe you can answer this question. My friend has asked me about this. I have no clue about it either. You are a purveyor of meats to New York City steakhouses. What’s with New York City steakhouses, serving big, thick strips of bacon with steak? I don’t really see it anywhere else. It’s only in New York City. Do you know what’s going on there?

Pat LaFrieda: You know, some say it’s the classic cut. I think I’m a long the lines of … I’m on your side on that one. I’m not really sure why that is. I’ve asked my elders about that very question. They said, “Well, why would I wanna eat the bacon, before I eat my steak?” I think you have some traditional New York City steakhouses that have been doing that forever. A lot of clientele have gotten accustomed to that. It has become a tradition. I’ve been to many steakhouses in which my guests have ordered bacon to come out, before the steak, as an appetizer. To me it doesn’t seem to fit, but it’s not for me to decide. It’s just for me to provide.

Brett McKay: Okay. That’s weird. Okay. It’s unsolved. Let’s get that guy from Unsolved Mysteries on it, if he’s still alive. Let’s shift gears to pork. There’s a lot in there. What do you think is the most overlooked, or cut of pork from folks that you think … Man, if people really embraced it they would get a lot of enjoyment from it.

Pat LaFrieda: I think the pork butt. The pork butt is the pork shoulder. In beef it would be the chuck. Why it’s called butt is because they used to be stored in big containers called, butts, and shipped up to Boston. The pork butt, or shoulder is very tender. With a pork butt, it’s very inexpensive. To slice one inch steaks from a pork butt, is really, just as good and tender as the center cut pork loin, or pork chops. I mean, it’s such a versatile cut, where, if you wanted to make pork stew, all the way to a pork steak, I’d make it from the pork butt. You’ll have a number of muscle groups that you’re cutting through, but they’re all tender. I think that’s the big takeaway from a pork butt.

Brett McKay: I like that. Well hey, Pat, where can go to learn more about the new book?

Pat LaFrieda: Well, the book on Amazon. If anyone wanted to know more about the book, you go onto our website, lefrieda.com. There’s more information there about the book. The book was really crafted and make with a lot of careful time to really show where each steak, or each cut comes from and it’s different characteristics. In that regard, some companies have bought it for their entire staff, that are in the meat business, just to use as guide. I find myself using it as a guide, when I’m trying to explain to a chef, where certain cuts come from, and what’s good about them and not. It’s a great guide. Again, it’s available on Amazon and to learn more about it, my websites a great place to go.

Brett McKay: Pat LeFrieda. Thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Pat LaFrieda: Thank you my friend. Thank you for having me on.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Pat LeFrieda. He’s the owner of Pat LeFrieda meat purveyors. He’s also the author of the new book, Meat; everything you need to know. It’s available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can also find out more information about his work at leFrieda.com. Also, check out our show notes at Awin.is/butcher, where you can find links to resources, where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another addition of, The Art Of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art Of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoyed the show, you got something out of it, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or stitcher. If you’ve done that already, I’d really appreciate it if you’d recommend us to a few friends, cause that’s how most people find out about the podcast. As always I appreciate your support. Until next time, this is Bret McKay, telling you to stay manly.