Editor’s note: This is a guest post from James “Buzz” Surwilo (of The Uncle Buzz Workout and Tree Felling fame).

The editors of the Art of Manliness have been requesting a how-to for making maple syrup since, well, they found out that I made a batch last spring. But it’s difficult to write authoritatively on an activity that you have only experienced once, and at that point, I demurred. So another maple syrup–or “sugarin'”–season has come and gone, and my family made our second batch, thus doubling my knowledge base on the subject to just above rank amateur. I now have the confidence to add a piece on making maple syrup to all the other half truths and misleading advice churning around on the internet.

Vermont, as everyone knows, is the birthplace of Chester “Chet the Jet“ Arthur, our 21st president. Maybe less well-known, we are the home of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, have the only state capital without a McDonalds, and have the greatest per capita number of trust fund supported hippies of any state. Vermont also leads the nation in maple syrup production, which, in some small part, I can now share the credit.

Every spring around here the media plays up the maple sugaring season, pushing the occasional cat-rescued-from-tree, naked-Governor-outruns-bears (really, last week), and inmates-add-pig-to-state-police-car-decals (really, last month) off the front page. Tourism brochures encourage visitors go and visit syrup producers, attend a maple syrup festival, ogle maple trees when the leaves turn color in the fall, and, most importantly, fork over some serious cash to bring a jug of the sweet stuff home. A maple tree graces the Vermont state flag. Local restaurant owners would close before serving Aunt Jemima to their customers. You get the message. Maple syrup is iconic in Vermont, and for 30 years, except for buying the occasional gallon, none of this was personal.

Maybe ten years ago or so I met a couple of people at my work who made their own maple syrup in their backyard, and also became friends with a co-worker, Bryan, whose brother and brother-in-law are commercial syrup producers. Somewhere in these chance encounters was the muse to try sugaring, but I was staggering ignorant of the process, which seemed to be part alchemy, part mysticism, and part quantum mechanics, with a vexing vernacular and with enough tightly held secrets as to put the Masons to shame. But making maple syrup is essentially collecting the tree sap and boiling it down into syrup, and I knew that the Native Americans in this region made maple syrup by throwing hot rocks in a hollowed-out tree trunk filled with sap. How hard could it be?

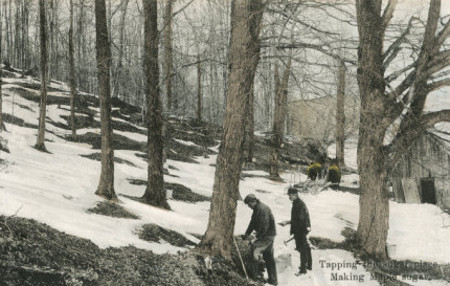

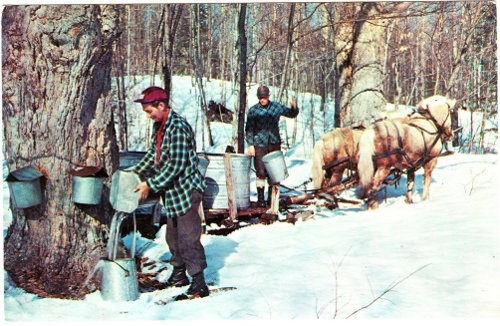

My first–brief–foray into maple sugaring was helping Bryan and his brother-in-law for a day a few years back. Most of the commercial syrup producers have switched from collecting the sap in individual buckets, to collecting it via a network of plastic tubing that runs from tree to tree to the “sugarhouse†where the sap is boiled. But there were still a number of buckets hanging off of maple trees where it wasn’t feasible to run lines. So our job on the cloudless, warm spring day was to walk through the woods collecting the sap from the buckets, empty them in a large tank in the back of a pickup truck, then off load that tank into an even larger tank at the sugarhouse, to be bled into the boiling apparatus. I won’t go into the details of a commercial syrup operation because (1) it isn’t germane to this article, and (2) it remains a great mystery to me, much like what happens behind the curtain in the Wizard of Oz. My takeaway lesson, though, was that the relaxed pace of the work, and the cognitive acuity needed to make quality syrup, lends itself to socializing and drinking a beer or two. I was going to like this hobby!

Two years ago my wife and I purchased a small cabin–known as a “camp†in these parts–on twelve and a half acres of forest in a rural area about 45 minutes from Montpelier, where we live. On the parcel were a number of large, accessible maple trees, known as a “sugarbush.†Now with maple trees of my very own, except for not having a clue about what I was doing, I had no excuses for not trying my hand at syrup making.

Sugarbush with buckets in place at Buzz and Deb’s “camp.”

In the spring, alternating warm days and below-freezing nights causes the sap in trees to flow. This happens in all trees, but not all trees’ sap contains sugar as the sugar maple’s does. Maple sap from the trees contains about 2% sugar, while finished syrup is between 66%-70% sugar. What that means is a lot of water must be boiled off to concentrate the sweetness. Once it’s at the proper consistency, the syrup must be filtered to remove impurities and packaged in sterile containers. Voila, liquid gold!

Sap from a sugar maple drips into a bucket.

Like most men, I am loathe to ask directions, be it to the highway entrance, to assembling a gas grill, or how to make maple syrup. Asking shows weakness; it shows dependence; it means that you probably actually liked those flowered gardening gloves that you got for Christmas. It gives the men who get asked directions a smug sense of advantage–of possessing some knowledge or skill, no matter how trivial, that you do not. This perceived supremacy, in men’s culture, gives them the right to treat you like an idiot, a right that most men gleefully exercise. And women think it’s as simple as rolling down the window and asking, “Where’s Elm Street?†Not hardly!

I tried to acquire information about maple syrup indirectly through banter around the water cooler, never asking questions per se–lest I let on to my ignorance–but prompting the discussion and making mental notes of the proceedings. There are plenty of women and families who “sugar,” but the people that I happen to know that do it are all guys, and sugaring takes (sometimes complicated) equipment, involves fire, requires you to get your hands dirty, and lends itself to BS-ing and bragging, so it’s exactly the type of subject men love to talk about. And this prompting technique was helpful, and I gleaned the rudiments of maple syrup production. But as with most experiences, hearing about something and doing it are entirely different.

Coincidentally, right about that time the local technical high school offered an evening “It’s Sugaring Time — How to Make Maple Syrup†course (and because this is Vermont, other courses in “Chainsaw Sharpening†and “Detoxifying Your Body With Herbsâ€) which I immediately signed up for. While the course was fun, and interesting, it was only marginally informative for my level of understanding, which was–and remains close to–zero. On the first day of class, the eight or so of us students sat down in the seats in the all-purpose shop class, and the co-teachers started right off by asking, “So…what do you want to learn?†No syllabus, no outline, no written anything, no preconceived thoughts on what information to convey–entirely seat-of-the-pants pedagogy. We “made†maple syrup in the school’s brand new, state of the art, commercial scale sugarhouse with its bewildering arrangement of stainless steel tanks and hoses, reverse osmosis machines, vacuum pumps, oil-fired boiler, gauges, and valves. “Made,†because a sugaring operation of that size is pretty automated. Our role was reduced to filtering and packaging the finished syrup. If I wasn’t adept at screwing caps on containers before, I am now. And we never did get into the woods to tap the trees and collect the raw sap.

As anyone who has ever pursued a hobby knows, the first step, and usually the most fun step, is buying stuff. There is no real work involved, little time committed, no pitfalls and frustrations yet, and there is that primal, but short-lived, felicity that every red-blooded, materialistic American gets when coming home with the goods. If I was going to make syrup, I had to acquire the paraphernalia, and that would edge me one step closer to succeeding.

The first item–or items–that I needed were the buckets that hang off the maple trees, and into which drips the sap. The rule of thumb is about 10 gallons of sap per tap on a good year, or about one quart of finished syrup. 10 taps should then give us 2-1/2 gallons of syrup, which seemed to be a reasonable and doable amount for a rookie.

Buckets ready to be hung from trees.

As the serious sugarmakers dispense with individual sap buckets in favor of plastic tubing, the galvanized metal buckets become readily available to the hobbyist. Around here, there is generally one or two ads on Craigslist for reasonably priced used buckets most times of the year, and more during the spring sugaring season. I paid, I believe, $7.00 for each bucket, lid, and stile (tap), for an initial investment of $70, while I see a new “3-tree starter kit,†being retailed by a commercial maple equipment supplier for $139.95. Hooray for Craigslist!

In order to get the maple sap out, you need, or course, to bore a hole into the tree. Wound it. Make it bleed. And try not to feel too guilty about it. A cordless drill is one of the few, common manly tools that I don’t own. Not that I wouldn’t want one, only Santa has stiffed me year after year. But I do have many friends with cordless drills, so I planned to just borrow one for the day. Meanwhile, because I had read that an old fashioned bit and brace works just fine for a small number of taps, I was keeping my eyes open at thrift stores and tag sales. Never pay retail! Never buy new!

So now I had what I needed to collect the sap, but the trees were scattered in the woods somewhere (although, I hoped relatively close to the road), and I would need something to agglomerate and tote the hoped-for copious volumes of sap back to my truck, as I planned to do the boiling at our house, 30 miles away. As luck would have it, a local, high volume restaurant sells empty, reclosable 5-gallon plastic containers which once held their frying oil. I bought a dozen–which probably made about a day’s worth of French fries for this place–at a buck a piece. Another score!

With drill and buckets in hand I ventured into our woods. Sugar maples are easy to identify when they are leafed out, but a little trickier when everything is bare. Luckily, I remember a scant amount of forestry from college 30 years ago, and tapped into the first 10 good sized maple trees I came to. The idea is to drill a 7/16†diameter hole about 1 ½ – 2 inches into the tree, and tap the stile into the hole. Onto the stile hooks the collection bucket, along with the bucket lid. All in all, very easy and guilt free. After all, trees don’t flinch or cry when perforated, and it isn’t as if nausea-inducing blood spurts out.

Buzz bores a hole into the tree in preparation for the insertion of the stile (tap), as Buddy the dog looks on.

Buzz’s wife Deb hangs a bucket on the tree.

With hopes high, Buzz checks to see how the sap is accumulating.

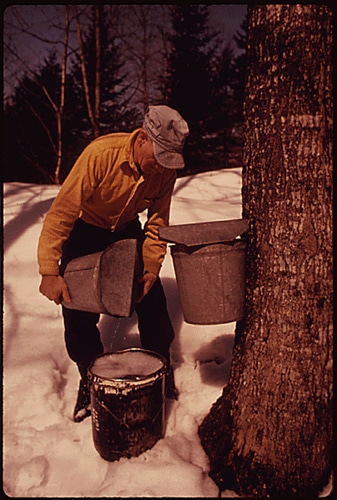

Buzz and a friend transfer the sap from the bucket to a 5-gallon container.

After a few weeks of driving from home to the sugarbush, checking the buckets every couple of days, I had burned about 100 gallons of gas, and had collected about 60 gallons of sap for the effort. Every drop seemed precious as a pearl, and I bemoaned inconsequential spill while transferring the sap from bucket to 5-gallon container.

Transporting the sap via pickup truck was a delicate business, but easier than pulling it by sled, as it was done not too many decades ago.

As I mentioned, maple sap becomes maple syrup by ridding it of water. And while big operations now employ reverse osmosis to partially concentrate the sap, making maple syrup always involves boiling the sap. And boiling some more. And boiling still more. It takes about 40 gallons of sap boiled down to make one gallon of syrup. To illustrate, think of the biggest stock pot that you own, fill it to the brim, then boil it down until about a quarter inch of liquid remains. That’s a 40 to 1 reduction. It takes a lot of time and it takes a lot of energy. And if you were to do it on your kitchen stove for any quantity of sap worth boiling, the steam would saturate the house. Not a good idea.

Some folks that I know make syrup on their gas barbeque grill, but that just didn’t have the romantic, agrarian ambiance that, in my way of thinking, was the essence of sugaring; it seemed like it would be cheating. Also, we heat our house with wood that I cut myself from our woods, and usually have an excess supply. Most often I’m like the grasshopper, fiddling away while the rest of society’s ants work diligently, but I enjoy the physicality of woodcutting, and an overfull woodshed is the result. With the wood being “free,” why would I burn tank after tank of propane? And so I decided that I’d built a free-standing concrete-block fireplace holding up an old, metal grate refrigerator shelf on which I’d place the boiling pans. Cheap, but effective.

I had also, over the course of time, purchased two new, and one used, big, 5 gallon, galvanized metal pots in which to boil the sap. Preferable would have been shallow pans, like restaurant steam table pans, as the more surface area on the flames the better, but I could never score these used, and new pans were priced well out of reach.

Once I had my Rube Goldberg boiling apparatus constructed and the fire stoked, I filled three pots about 2/3 full of sap. And then…nothing really happened. Or, it was very anticlimactic. Up until the sap is set on the heat source, everything was hard work, or at least taking action, or thoughtful consideration for the next step. But suddenly I was left with nothing immediate to do, as it takes a long while for the sap to reach the boiling point, and even longer for it to begin to evaporate appreciably. It takes a little getting used to, this inertia, but I quickly acclimated to throwing an occasional log on the fire, and replenishing the pots with sap. Now for that beer and some deep introspection!

The boiling process began in the late afternoon, and went into the evening, then into the night. I found that a good, roaring fire made the pots boil like crazy, but as soon as the fire would ebb slightly, so noticeably would the rate of the boil. Before long I got the system down so that every 25 minutes or so I needed to stoke the fire and add sap to the three pots.

By and by, as night turned to late night, fatigue overcame me. I knew that I would never be able to stay awake until morning, but by the same token, the sap needed to boil until it was syrup, and that would take hours more. Luckily, we have a finished basement with a futon that’s usually reserved for the dog. But about midnight, I grabbed an alarm clock, booted the dog off, set the alarm 25 minutes ahead, and collapsed on the futon–clothes, boots, and all. In 25 minutes the alarm went off; I got up, stumbled outside, loaded up the fire with wood, poured raw sap into the boiling pots, went back down the cellar, reset the alarm, and, surprisingly, immediately dropped off to sleep. I repeated this process every 25 minutes until dawn, and each time the alarm went off, jarring my slumber, I would have no idea where I was, or what was going on. You would think that somehow, after enough repetition, some small part of my brain would be cognizant of what was happening, what was expected. But no, I would dependably wake up with total amnesia, thinking, “Where I am? What am I doing here?â€

So it’s 7 o’clock in the morning, and I’ve been up and down all night babying the sap into syrup. I’m tired, smelling of smoke, unshaven, hair askew, and wearing the same clothes for the past 24 hours. All of which, if it was the weekend, would be pretty normal, but not on a Tuesday, when I should have be heading off to work. The almost-ready liquid had been condensed into one pot, and we were ready for the final steps. Because getting the syrup to the correct consistency is the trickiest part of the whole operation, I finished the last bit of boiling on the kitchen stove. There was so little water that needed to be evaporated that I had no worries of peeling the wallpaper off the walls. Serious sugarers use a hydrometer to measure the density of the liquid to know when the syrup is syrup, but for my purposes, a candy thermometer works fine. The sap will boil and boil at close to the boiling point of water, 212oF, for a long time, then climb rapidly when the sugar content rises. When it hits 219oF, it’s done. And it doesn’t take much more boiling at that point to turn it into maple molasses, then maple cement.

But we paid close attention and hit the 219 mark, and it looked like syrup, anyway. The final step in the process was to filter out all the pine needles, bird turds, and other junk that may have fallen into the boiling pans. Filtering is also necessary to get out the minerals, called niter, or sugar sand, that are naturally present in the sap. Without filtering, the syrup is unappealingly cloudy, and could have gritty texture. Certainly not desired after all this work. Syrup is filtered best when it’s hot out of the pan; once it cools and thickens it tends to stay on the filter rather than passing through. And you want to get the hot, sterile syrup into sterile containers, before any nasty germs can take hold. The first two years of sugaring we just used multiple layers of cheesecloth for the filter medium. It worked to a point, but we had to filter the syrup twice to get most of the niter out, and the cheesecloth soaks up a lot of syrup, which seemed wasteful. I’ve now invested in genuine cloth syrup filters, but I’ll have to wait until next year to try them.

We filtered the syrup directly into pre-sterilized pint and quart mason jars. Once filled to about ¼ from the top, we laid them on their sides to ensure that the still hot liquid touched the entire inside of the jar, to make doubly certain that the syrup wouldn’t spoil. When we were done, that first year, we stood back and admired our gallon and a half of syrup! Cool!

The finished product: liquid gold!

Now that I’ve done it a couple of times, I really see the appeal to backyard sugaring. I don’t know, and don’t want to know the economics. But there is something almost magical in the process: the creation of something out of nothing with your own two hands. When it’s springtime in Vermont, a man’s sap, like the trees’, is flowing. Sugaring is a great way to throw off winter’s yoke. It’s being outdoors performing physical tasks, contemplatively tending a fire under starry skies, involving the family in a common interest, mentally challenging yourself to invent clever ways to make the process better, and then ending up with a very unique and delicious product. I heard countless times that maple sugaring gets in your system, that it becomes a simple highlight of the year, and now I know why.

Photographs by Deborah Johnson-Surwilo