Nowadays when you hear the word “spam,†you probably think of the unwanted emails you get from unknown sources soliciting you for money and information. Little do many people know, the term actually refers to and originates from the glorious canned luncheon meat of the same name. In the 90s when email became popular, users began referring to a classic Monty Python sketch to talk about these unwanted but ubiquitous messages. In the sketch, a couple is dining at a restaurant in which Spam is part of nearly every item on the menu, much to the chagrin of the wife. It’s a funny and weird look at people’s love/hate relationship with the meat:

Before being the butt of a joke in 1970, though, it was on the losing end of soldiers’ jokes during WWII. As we’ll see later, Spam supplied our armed forces with many of their meals. Prior to WWII, however, it enjoyed a brief stint as a popular and innovative product born from the ingenuity of southern Minnesotans.

Since its inception in 1937, Spam has earned heaping amounts of both praise and scorn. It’s truly one of those foods that you either love or hate (and in my experience, the haters often haven’t even tried it!). As I’m sure you can already tell, I rather enjoy Spam. And I should; I was born in Spamtown, USA (Austin, MN, that is), where Hormel is headquartered and where Spam is produced. There’s even a fantastic Spam museum there, which is surprisingly popular among Hawaiians visiting the mainland (we’ll see why a bit later) as well as foreign tourists.

Today, we’re going to explore Spam’s fascinating, oscillating history, find out what this gelatinous and confusing block of meat really is, and share some recipes for you to try out. Tasty and cheap, Spam’s been a food icon for over 75 years, and it’s time you knew the story behind it and put some on your plate.

Spam’s Humble Beginnings

In the late 1920s, canned meat became a common source of food for commercial endeavors — restaurants, hotels, even butcher shops and delis. As the depression took hold, its popularity increased, as companies didn’t wish to be held hostage by fresh meat’s high prices nor by its seasonality. (Believe or not, fresh and natural meat is seasonal!) Whole canned hams and chickens, on the other hand, were always available, lasted nearly forever, and were cheap and easy to cook — slice and heat and you’re done!

Hormel was the leader for this category of food in both inventiveness and food quality. They were one of the first major companies to try canning whole meats, and used quality products to do so. This included the use of pork shoulder, which is a decent cut of meat, but mostly ignored in that era because of the time and energy it took to get the meat off the bone. Hormel’s product was more expensive, so competitors just undercut prices with cheaper ingredients (leftover parts, basically), and the now-famed Hormel had to do something different to stand out. Company president Jay Hormel had an idea for a household product, something family-sized, that would set Hormel apart from the rest.

And so in 1937, Spam was born, after two years of testing various products and recipes. The name was the result of a contest that Jay Hormel held at his mansion in southern Minnesota as part of a New Year’s Eve party. A dapper fellow named Ken Daigneau, brother of a Hormel VP, shouted out “Spam!†almost instantly. He was an actor from New York, but Spam would be his crowning achievement — probably not what he had in mind when he started his career. The word stands for either spiced ham, or shoulder of pork and ham, which is odd, as the original product didn’t actually have any ham in it! It was added in later, as so many people just assumed it was there. It’s likely that after tasting the yet-unnamed meat at the party, Mr. Daigneau thought it mainly a ham product.

Supposedly only a handful of Hormel executives know the truth about what the name stands for, but my hunch is that nobody actually knows, and shoulder of pork and ham would be most appropriate, as that is what Spam is. Other names considered were Brunch and Spic (the latter being an old English term for fat or grease rather than the derogatory meaning we know today) — thankfully neither of those were the winner.

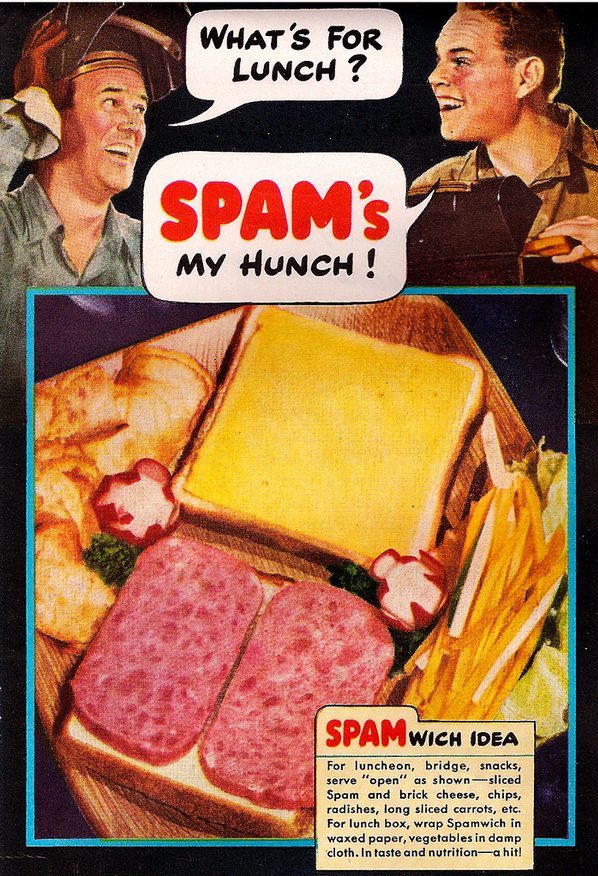

Selling the new product was still a tough go, however. People hadn’t seen canned meat on grocery store shelves and were wary of a meat product that didn’t have to be refrigerated. So Hormel took to their creative department and made sure they saturated newspapers, radio waves, and women’s magazines with punchy ads. It was sold to housewives as a “miracle meat†— it didn’t need “pampering in the refrigerator,†could be cooked in literally minutes, and tasted delicious to boot! It was also versatile, as one slogan chimed, “Slice it, dice it, fry it, bake it. Cold or hot, Spam hits the spot.†The ads worked; by 1940, 70% of Americans were eating Spam and the company had sold over 40 million cans.

What Is Spam?

People tend to believe that Spam is made from leftover pig parts and chock full of artificial additives, but it’s actually downright wholesome compared to other processed foods; its only ingredients are pork shoulder, ham, salt, sugar, and some sodium nitrite. Eating fast food is definitely much worse for you than Spam.

While you’ll see a lot of sources out there saying the canned meat is made mostly of ham, it’s about 90% pork shoulder and 10% ham. It contains zero non-meat fillers, nor any snouts, lips, ears, etc. While the FDA allows tongue and other mystery pig parts in luncheon meat, Hormel doesn’t use any in Spam. The pink color, which tends to understandably throw people off, is entirely from the sodium nitrite, which is a preservative. It’s not all that good for you — no preservative really is — but it’s the same thing found in hot dogs, deli meats, etc. A little bit of it now and then won’t kill ya.

Perhaps the most offensive trait of Spam is the gloopy gel that coats the meat and tends to make a lovely vacuum-sucking sound as it comes out of the tin. This gel that coats and coaxes the meat out of the can is called aspic — basically the stock fat that comes from the meat after it’s cooked. Don’t worry, it’s a natural thing, not some added chemical to help it slide out of the can, as many folks assume. In fact, this gelatinous goo is quite good for you, as it’s almost entirely protein. It should be noted that as of a few years ago there is a small amount of potato starch in Spam, as to reduce the gooey coating a little bit.

Spam, uniquely, is cooked in its can. The ingredients are vacuum mixed, then canned, then cooked hydrostatically — meaning water is the source of the heat. This method of cooking the meat in the tin is why Spam has a near-indefinite shelf-life.

How WWII Changed Spam Forever

While spam was already a national hit by the time WWII began, the war would take its ubiquity to a whole new level. The military loved canned luncheon meat because it was nutritious, filling, cheap, easily transportable, and had an extremely long shelf-life. By the time the war was over, Hormel had provided 150 million pounds of meat to the war effort, and during that time, 90 percent of the company’s canned goods were going to the military.

While widespread dissemination of spam made Jay Hormel and his company rich, the soldiers on the receiving end of shipments were less happy about the canned meat’s infiltration of their rations. You would be too if it’s nearly all you ate for years on the front lines. It was meant to be served at bases and camps as a B ration along with a variety of other foods, but various distribution difficulties and other wartime issues meant that GIs were routinely getting served Spam 2-3 times per day. WWII veteran Thomas Clancy recalls, “You had it fried in the morning with chemical eggs. They burned it black as a painted door. They’d cut it up and put it into stews. They put it in sandwiches. They backed it with tomato sauce. They gave it to us on the beach. You got so you really hated it.â€

Because of its pervasiveness overseas, it earned catchphrases like “ham that didn’t pass its physical,†“meat loaf without basic training,†and “the real reason war was hell.â€

Unbeknownst to soldiers, though, military Spam was different than U.S. consumer Spam. It was sent in 6lb tins, didn’t contain ham, and was extra cooked and salted to deal with any bitter cold and brutally hot environment the meat might be found in. Although they weren’t getting “real†Spam, the soldiers spared no effort railing against it, writing up poems, drawing cartoons, and sending Jay Hormel thousands and thousands of hate-filled letters. One anonymous poem became especially (in)famous:

“For breakfast they will fry it;

For supper it is baked;

For dinner it goes delicate —

They have it pat-a-caked.

Next morning it’s with flapjacks,

Or maybe powdered eggs —

For God’s sake where do they get it?

It must come in by kegs.Oh, surely for the evening meal

They’ll cook up something new!

But the cooks they are uncanny,

Now the Spam is in the stew.

And thus the endless cycle goes;

It never seems to cease —

There’s Spam in cake and Spam in pie

And Spam in rancid grease.â€

Such scorn ate at Mr. Hormel. In an interview in 1945, he said “Sometimes I wonder if we shouldn’t have…†but couldn’t bear to finish the sentence. The interviewer noted “We got the distinct impression that being responsible for Spam might be too great a burden for any one man.â€

Because of their distaste for Spam as a foodstuff, soldiers found a variety of other uses for it during wartime. Its greasy fattiness made it useful in numerous ways: as a skin conditioner, as gun lubricant, as waterproofing material for boots and tents, and even mixed with lighter fluid or gasoline as a candle. Some soldiers inked Spam slices to use as playing cards and were able to play poker with them for a period of multiple months. Even the discarded tins were repurposed to make pots and pans and even toy trains.

While the men who served abroad may have loathed it (for its repetition if nothing else), housewives both stateside and in England sung its praises. One British woman noted its “fragrant aroma†and also “its perfect flavour and textureâ€; another said that champagne and caviar didn’t stand up to “precious, succulent, beautiful Spam.†Rosie the Riveter even promoted the meat in one ad.

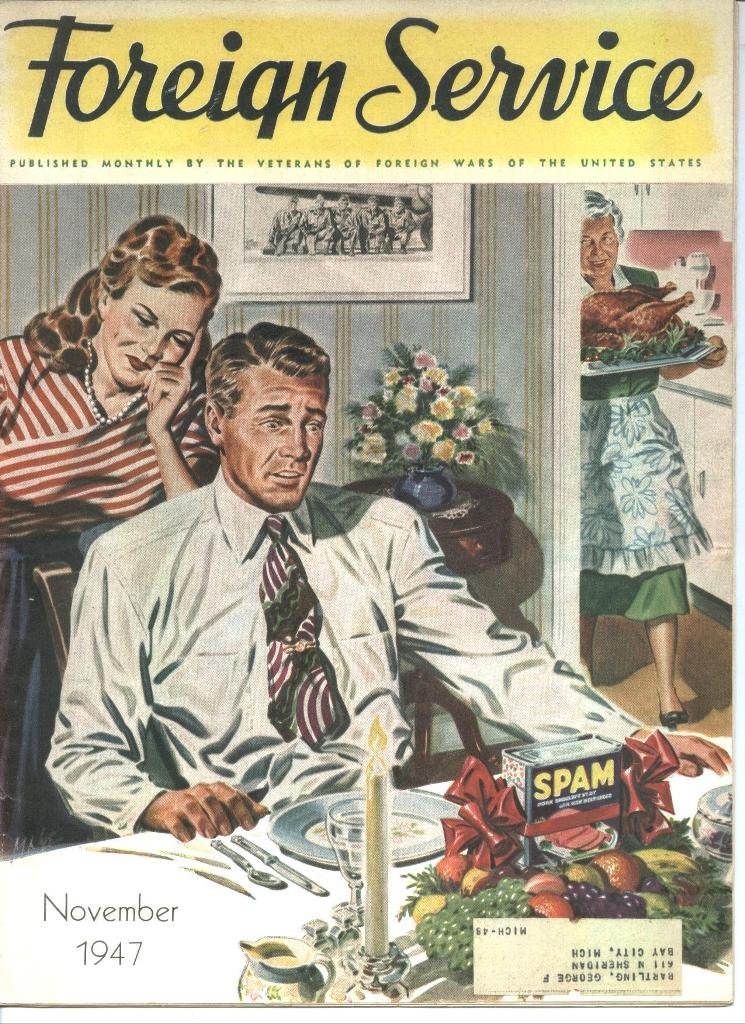

This dichotomy of course led to some misunderstandings at home. It was joked that a man’s worst nightmare would be coming home from the war only to find Spam on the plate for his first meal back:

Even with all the negativity, Spam actually enjoyed a post-war boom. For every vocal anti-Spam soldier, there were plenty who came to enjoy it. Beyond that, Jay Hormel was well aware of the vitriol, and produced another big ad campaign to fight it: the Hormel girls.

After the war ended, Hormel created a regiment of 60 traveling performers, most of them being war vets. It doubled as an opportunity to provide jobs for veteran women, and it drummed up positive support for products like Spam and Dinty Moore. At one point in the early 50s Music with the Hormel Girls was a top-rated radio show on three different networks. The show was an early casualty of TV, but the impact for Spam was solidified, and while the country didn’t necessarily love their canned meat, folks’ attitude towards it became more neutral than downright negative.

Spam Today

Spam was used sparingly during the Korean War, and by the 90s was phased out of use in military rations altogether. Ironically, given its former ubiquity, Spam is a semi-popular item at commissaries around the world because it’s different than what soldiers would normally eat from the mess hall.

Even amongst the general public, spam is enjoying a bit of a renaissance. Given its cheap price, it unsurprisingly enjoyed an upswing during the 2008 recession. And the product recently celebrated its 75th birthday, which brought a little bit of spotlight back to Spam.

Much like Pabst Blue Ribbon, Spam offers a nostalgic throwback to a different era. Yet an affinity for the meat need hardly be a hipster affectation; it’s a truly frugal, convenient, and versatile food. Writers from culture mags and newspapers have been trying it out, and often are surprisingly delighted with the results; as one writer noted, “It was pretty tasty. It made a nice lunch and I ate every bit of it… Frankly, if I didn’t know I was eating Spam I would have thought it was real chorizo.†It’s even started appearing in haute cuisine, serving as a lowbrow highlight on highbrow menus.

Spam is in fact the 120th best-selling product out of the 30,000 products that the average grocery store carries. The southeast, particularly, seems to have an affinity, with the average person eating one can per year — twice the national average.

Hawaii, though, is where Spam really shines. Inhabitants there consume an average of four cans per year, and it’s often listed on fast food menus, sold in gas stations as snacks, and even featured in sit-down establishments. It started during the war, of course, when refrigeration was hard to come by and so was fresh meat. Spam would stay fresh out of doors for long periods of time, and became the lunch of choice for local plantation workers. It also became an important source of protein when Japanese-Hawaiians were restricted from deep sea fishing by the U.S. government. Spam simply replaced the fish, and it became a food staple. Unlike weary soldiers, Hawaiians held fast to their love of Spam — probably because it was at least partially their choice and not something they were forced to eat.

Beyond the U.S., Spam remains popular worldwide and is available in 44 countries. It’s especially popular in East Asian countries, as it became a staple of the post-war recovery. Korea is in fact the second largest consumer of Spam (behind America), and it’s considered a little bit of a delicacy. Hormel has sold over 8 billion cans of the miracle meat since 1937, and the line has recently expanded to include flavors like Teriyaki, Chorizo, Jalapeno, and more.

I tried my hand at a few Spam recipes with three different varieties of the meat. One is an old recipe of my grandma’s that I grew up loving, one is a traditional Hawaiian staple, and one is a simple breakfast creation:

Recipes

Grandma’s Pizza Burgers

This recipe was always one of my favorites growing up. It’s been passed down a couple generations, and now I pass it onto our Art of Manliness readers. Use it well. This makes a big batch, as Grandma always served a big crowd and froze the leftovers. This should make 20 pizza burgers or so, and most people will eat 2-3.

Ingredients

- 1 can Spam (regular)

- 2lb ground beef

- 1 16oz can pizza sauce

- 1 tbsp sage

- 1 tbsp oregano

- mozzarella cheese (sliced)

- English muffins

Directions

- Preheat oven to 400 degrees

- Brown the beef and drain

- Dice Spam

- Mix together beef, Spam, pizza sauce, sage, and oregano

- Spoon mixture onto open-faced English muffin

- Top with a slice of mozzarella cheese

- Place in oven for 10 minutes, until cheese is melted

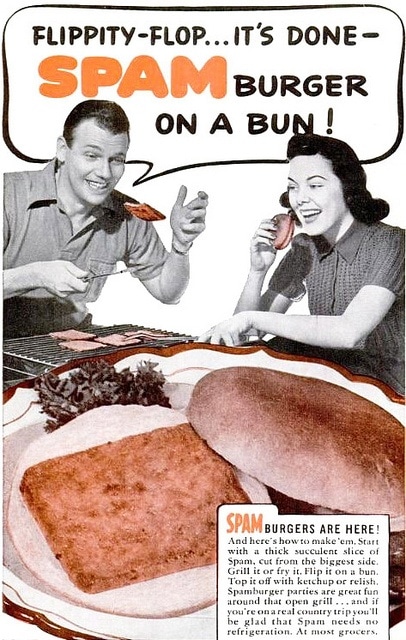

Hawaiian Spamburger

While the quintessential Hawaiian Spam dish is Spam musubi, the combo of Spam and pineapple on a sandwich is also found all over the islands. This is a recipe you can really make your own by adding beef or other meats to it, as well as various cheeses and vegetables.

Ingredients

- Spam (jalapeno)

- pineapple (sliced or ringed rather than chunked)

- mayo

- Swiss cheese

- onion bun (my preference, but you can use any bun)

Directions

- Preheat grill to medium-high

- Slice Spam — I used two half-inch slices

- Slice pineapple — again, I used two half-inch slices, enough to pretty much cover the bun

- Place Spam and pineapple on grill for about 5-7 minutes, flipping once

- Apply mayo to bun, then add Spam, pineapple, and cheese in your your desired order

Spam & Eggs Breakfast Burrito

This bad boy is simple, but fills you up in the morning and tastes great. I made this up based on the simple breakfast burritos I enjoy on a regular basis, so use this as a jumping off point.

Ingredients

- 1 large tortilla

- 3 eggs

- Spam (chorizo)

- shredded cheese

- green salsa (I love Mrs. Renfro’s hot green)

Directions

- Preheat skillet over medium-high heat

- Dice one-quarter to one-third of a can of Spam

- Throw the Spam in the skillet and let it heat for 5 min on its own

- Toss in the eggs and scramble them with the Spam

- Once done, place on tortilla, add cheese and salsa, and enjoy!

Do you have memories of Spam from the military or from growing up? What’s your favorite Spam creation? I’d love to hear it!

_____________________

Source:

Spam: A Biography by Carolyn Wyman