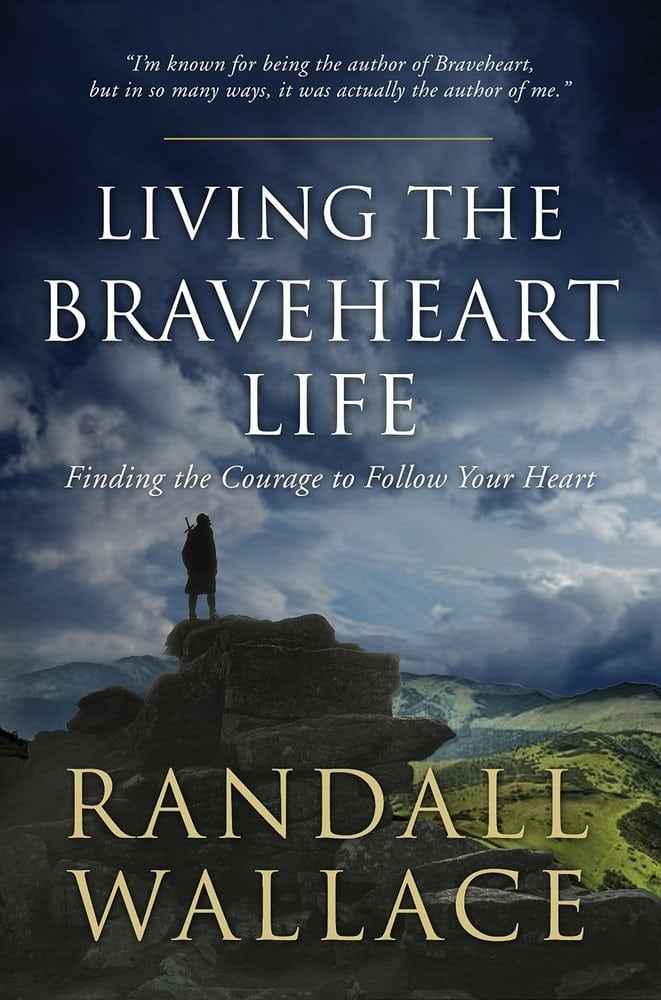

It’s been 20 years since the film Braveheart was released. If you’re a man who came of age in the 90s, it was likely a cultural touchstone for you. I remember watching it before football games to get pumped up. In commemoration of the 20th anniversary of Braveheart’s release, the man who wrote the screenplay has published a book recounting the creative and spiritual energy that went into writing Braveheart as well as the lessons in life and manhood that he’s learned on his life’s journey. His name is Randall Wallace and his new book is Living the Braveheart Life. Today on the podcast, Randall and I discuss the genesis of Braveheart as well as lessons on living that all men can take from the life of William Wallace.

Show Highlights

- Where Randall got the inspiration for Braveheart

- The role of fathers in living the Braveheart Life

- Why a man needs friends and brotherhood

- Why you need to cultivate both hard and soft virtues to live the Braveheart Life

- The Braveheart Moments every man will face

- Why faith, love, honor, and courage are really the same thing

- Why sometimes following your heart can be the scariest thing you can do (and how to overcome it)

- And much more!

If you’re a fan of Braveheart the movie, you’ll definitely enjoy this behind the scenes look at the creative and even spiritual birth of the film. Pick up a copy of Living the Braveheart Life on Amazon today.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. Believe it or not we’re coming up on the twentieth anniversary of the release of the movie Brave Heart. If you’re like a lot of men who grew up in the nineties this movie might’ve been a touchstone for you. At least it was for me. I remember when I played football, on game days, my buddies and I would get together to watch this movie to get pumped up. Watching William Wallace rouse his troops, the battle scenes, watching the final scene where he yells out freedom before he get’s executed. It’s a movie that fills you with thumos and inspires you. Today on the podcast I have the man who created the William Wallace that we know because of Braveheart.

His name is Randall Wallace. He is a screenwriter, director, producer. Also a song writer. He recently published a book called Living the Braveheart Life: Find the Courage to Follow your Heart. It’s the story of how his life lead up to the creation of Braveheart. Really powerful book. It’s a story of courage, of passion, of love, of family, of setbacks, of faith. Today on the podcast we discuss all these topics and the lessons we can learn from the film Braveheart. Really powerful discussion. One of my favorites I’ve had in a long time on the podcast. You think you’re really going to get a lot out of this. Without further ado, Randall Wallace, Living the Braveheart Life. Randall Wallace, welcome to the show.

Randall Wallace: Great to be with you Bret.

Brett McKay: You are a screenwriter, producer, director, song writer, who’s worked on a lot of touchstone films in American cinema. The only I think a lot of men particularly know you about, it was because of your breakthrough, was Braveheart. We’re coming up on the Twentieth anniversary of it. I guess it is the twentieth anniversary, which is crazy. It makes me feel old. I remember when it came out.

Randall Wallace: Think how it makes me feel. I can’t believe it’s twenty years either.

Brett McKay: It’s nuts. Along with this you come out with a book called Living the Braveheart Life which is a really great book. It’s part memoir, part insights on being an artist, parts insights into life, and what I loved about it, it seemed like the book Living the Braveheart Life was really the story of how writing Braveheart helped you write the story of your own life.

Randall Wallace: Exactly.

Brett McKay: I’m curious. Let’s talk about that. What was your life like before Braveheart and where did the inspiration come to write Braveheart from what I understand the story of William Wallace there really isn’t that much history about them. We know little fragments about him because you were able to develop this really enriching story about him and Robert the Bruce.

Randall Wallace: The literal history of William Wallace is known almost not at all. Winston Churchill, in his series of books called A History of the English Speaking Peoples mentions William Wallace and says that almost nothing is known about him in terms of literal historical fact but his legends have inspired the Scottish people for centuries. That’s the way I came across the story. I was looking for my own family heritage. My wife was pregnant with our first son and she knew her lineage back on all sides for many generations because she has Mormon ancestors. Because she knew hers I wanted to have some balance and know mine and was looking for my roots in Scotland and came across the statue of William Wallace and the fact that very little was known about him.

On a deeper level, to go back to your question, my life before Braveheart was, in my view, really rich. I grew up in the south. I grew up in a really staunch Protestant family. Tent revivals. Church all the time. In some ways that sounds like torture to people and in some ways it was but I was exposed to the greatest literature of the most magnificent music. Orators who could hold an audience for hours on end. Of course, far more important than that I was exposed to Christianity and the story of Jesus of Nazareth. That was always important to me. I wanted to live my life for some purpose greater than my own appetites and I was inspired by the story of Jesus more than any other.

I was talking with my family pastor who asked me if I felt the call to be a minister. I said, I don’t though I know it’s the greatest calling anyone could have. He said, you’re wrong. The greatest calling you can have is the one God has for you. That was as if I had been knighted, Brett, it was feeling that someone had released me to do everything I wanted to do in life or to try whatever I wanted to try. I was really successful at school. I went to Duke University. I majored in religion and had minor studies in Russian and creative writing. I had a time when I wanted to join the Marine Corps and their Platoon Leader Corps and then the My Lai Massacre happened. I saw that war as being in a stage that was not something I wanted to go be a part of but I really admired the people who had put their lives on the line for their county.

I’ve struggled with being a song writer, been to Los Angeles. I got into television writing and had a lot of success there. Then had some dark moments and it was in those dark moments that I came to write Braveheart. The answer to why I feel that writing Braveheart in some ways writing my own life is that the whole situation of my life boiled up into the story of Braveheart. A man who has to stand on the battle field and say I will live or die right here and living doesn’t necessarily mean that my body survives this battle but I will really live. That’s where every man dies, not every man will live, this came from and it’s where the whole trajectory that of my life, i believe, was set in the decision to write what I wanted to see and stories that I wanted to hear myself and the kind of stories I wanted to tell my own sons. Not what I thought Hollywood wanted me to be or Hollywood wanted to buy.

Brett McKay: That’s amazing. You were saying that line, every man dies but not every man lives. I get chills every time I hear it. It’s so evocative. I love about Braveheart and I think why it resonates with so many people, and particularly men, is because there’s gore, there’s battles, there’s violence, there’s that, but it hits on these really deep visceral ideas that just get you to the bone. You talk about this in The Braveheart Life. For example, you talk about how both Braveheart and Living a Braveheart Life is about fathers and sons and the relationship. In your book you talked a lot about how your own father and his role in shaping you as a man. Can you tell us a little bit about your dad and how he helped you become the man you are today?

Randall Wallace: Yeah. That’s, in some ways, the richest question in life and Brett I loved that you used the word visceral. We somehow want to make a separation between our minds and our bodies and our spirits. The word soul to some people means soul like soul music, is powerful and down to our core, but other people use it as if there’s some disembodied thing. This ghosty mist that somehow are being, my father connected me to life and the way we relate to our fathers, I think, is as profound a relationship as we ever have. It’s a part of the way we relate to our sons, the way we relate to our wives, or our daughters, our friends, and the way we relate to ourselves. Our dads give us our first taste of our own identity. Especially as men. What does it mean to be a man? We look to our fathers.

My father was really different from me on paper and if you looked at us we seemed so different. My father was a much more compact man than I am. I’m long and slender and my father was much shorter. I loved every sport there was. If it was a ball or a bat or about running into each other or punching something I wanted to do it. My father saw absolutely no use in running up and down a field. He couldn’t see how that made money and my dad’s whole life was about how to survive. He was a child of The Depression and of World War two. In my parents generation the worst sins a person could committee were laziness and cowardice. That was understandable since economic survival was so vital to them, being children of The Depression. My father, at fourteen years old, went to work full time. Was very smart but he had no one to encourage him to go to college and his own father had died before he was born.

My father would take my sister and me when we were very young to a graveyard and we would stare at a monument, a granite monument, that said Wallace on it. My father would say, this is my father. We’d never met him, had not really even seen pictures of him. It was in some ways mysterious to us why our father would want us to look at that stone. In some ways I think it’s because he was trying to wrap his own mind around who his father was and the idea that this man who didn’t have a father of his own, not a father who was breathing when he took his first breath, should become the greatest of fathers. Caring. I once said to somebody, my father may not have been a perfect man but you couldn’t prove that by me. In my mind he was because he never raised his voice to us, he never raised his voice to my mother. He never struck her. He never drank. He never embarrassed us. We were always proud of our father.

He was a salesman and I have always felt if he were alive today and we were to send him to Afghanistan or Iraq, those people would become our friends because he would go find something to like about them. He would show that to the world and to himself. He would see any person and recognize their value. One of the most moving things, my father died at the end of our making of We Were Soldiers. The last time I saw him he was on the set of our movie. The last time I saw him before he went into the hospital and got sick. When he passed away I wrote the lyrics to the hymn, Mansions of the Lord, about my father. When I was back working on the post production of the movie one of the Vietnamese guys who worked on the movie came by. I tell the story in the book. He came up to me and in this broken English he said, Mr. Randy, I’m so sad about your father. I said, thank you very much and he said, I spoke with your father.

I said, thank you, let’s get back to work, because I didn’t want to get emotional again. It was only like a week after my father’s funeral. This young man said, no, you listen to me. I stopped and he said, your father asked me where is your father? I said, my father died in Vietnam, and your father said to me, then I’ll be your father. Complete stranger. It moves me now. I can barely tell the story. I’m quick to add that I told this guy very fast, listen, if you think that makes you an heir and you’re going to get any inheritance you can give that up. You’re not getting any money. That was the way my father was. He didn’t want me to be a writer. He wanted me to do something secure, as every father wants to see their sons be safe. Yet, he was proud of me for going out into the battle field of Hollywood and no one was more proud of Braveheart or anything else I did than my father.

Brett McKay: One thing about fathers, I think a lot of men have experienced this, and women too, with their parents is that, you think they’re superheros, that they’re invincible?

Randall Wallace: Yes.

Brett McKay: Then there’s always that moment. Something happens in their life and you see the chink in the armor for the first time and you see that they’re vulnerable and that they’re not superheros. You had that experience with your dad. Can you talk a little bit about that? Even though it was his darkest moment how have you became stronger or how he became stronger from it?

Randall Wallace: That’s been, in may ways, the great mystery of my life and it’s something that I refer to in the book as the wound, that I realize as you say, my father was wounded under his armor and he was bleeding there and maybe had always been in part because he didn’t have a father of his own, in part because of what the loss of her young husband had done to my grandmother and the way she had been to raise him. When my father who had had a really meteoric rise in business in the nineteen fifties, he had gone from being an apprentice salesman trainee in a national candy company to being a divisional sales manager. He had several states, the salesman, all those states. He had a swagger and he had a confidence. He was never over confident.

He lived really frugally. Far below our means as I would come to find out later. The company was sold to a bunch of MBAs who believed the way to increase profits was to fire all the old guys that were making high salaries. He was one of the old guys at thirty-eight. They fired him and the idea that anybody would fire my father just broke him. He had never experienced anything like failure. He had been trained by his mother that he had to be perfect in everything. The idea that anybody would not want him on a company that he had given his heart and soul to really shattered him. I also think he felt he didn’t have any safety net. He began to doubt his own strength, his own confidence. I say in the book that we’re all have to see ourselves as fathers even if it’s not biological father, but you have to find a father and you had to be father even if it’s not your biological child.

You need to be a teacher and have a teacher. You need to be a warrior and be in the company of warriors. I believe my father lost his warriors spirit for a time and as you say, it was devastating to him and devastating to us to see our father who was also so confident, always knew what to do, and to see him have a nervous breakdown. What it also did for me, Brett, was when the time came when I thought this was about to happen to me, when I felt my own confidence and my own nerves and even my own body rebelling, when I felt so desperate that my career seemed to be unraveling, and I had always used work as my weapon. Determination. When I started my career I said to myself, I can’t guarantee that I have the talent to make it but what will never stop me will be a fear of failure or a lack of trying.

I found the time in my life when I was afraid and couldn’t even seem to get myself out of this cramp of emotion. I remembered my father and the way he had hit the bottom and then he had worked his way back to the top and a top much higher than you’d ever thought. That’s what happened with me. I got down on my knees and prayed sincerely, if I go down in this fight let me go down with my flag flying, not worshiping a false idol of what Hollywood says we should go after and be. Let me write the kind of story that is me, that give me goosebumps. That brings tears to my eyes or makes me laugh out loud. I will do that and I will take whatever the result is. Had it not been for my father showing me the way a man is, my father couldn’t teach me to write but he could show me what a man was. That’s what a father is.

Brett McKay: I love that. You called those moments braveheart moments. Moments where you have to dig deep and really find out what you really believe in and then go for that.

Randall Wallace: Exactly. You’ve got to find out. Sometimes you want to say, I want to follow my beliefs but times come when you go, I’m not sure what I believe. You’re right. That’s part of a braveheart moment.

Brett McKay: Besides fathers, friends, and brothers, and sisters plays a big role in Living the Braveheart Life and you talked about one of your friends in particular that I wanted to meet the guy after I read about him. It’s Bob from Afghanistan. Can you tell us a little bit about Bob and how he helped you maybe uncover the braveheart life in yourself?

Randall Wallace: Yeah. I met this guy through a funny circumstance that I describe in the book. When I met him I thought he was exactly the kind of guy that I would hate. He’s from Afghanistan. As I say in the book he looked like a Middle Eastern lounge lizard to me except that he was so strong and there was something different. When I say a lounge lizard I mean that he was wearing Gucci clothes and Armani suites when I was in shorts and a T-shirt. He was just so elegant and I was so rough and country. I just thought, here’s a guy I’ll have nothing in common with but I sat down across from him the first time we ever spoke and I liked him instantly. He had, first of all, a huge manhood about him.

He was strong and tough in the kind of strength that makes a man look you right in the eye without a kind of challenge, just with a complete confidence in how he is. Just this great quick laugh. A poetry in his soul. He turned out to be from Afghanistan. I met him years and years before Afghanistan became to us what it is today of a place where we were bogged down in war. His father was the head man of the Helmand Province which is today, and it was then the way it is today, this hotbed of rebels and independents. There’s a garbage truck outside and I’m going to pause for just a second. Shut the door.

Brett McKay: You’re fine.

Randall Wallace: Knowing that you can edit.

Brett McKay: Yep, we’re good.

Randall Wallace: Bob from Afghanistan is the son of the man who was the chief, the head man, the godfather, if you will, of the entire Helmand Province and his mother was part of the royal family of Afghanistan. He had this incredibly rich background in Afghanistan that he had come to America with a few hundred dollars in his pocket, knowing only a couple of words of English. He worked three or four jobs. He was educated, his formal education here, at a community college and he became a spectacularly business man. What he taught me was that here he was, from the other side of the world, from a culture radically different from mine. I grew up in a Christian family. He grew up with a mother who prayed multiple times a day and his father was head of this entire Muslim culture.

He does not himself practice Islam and he and I have talked a great deal about my faith but I must say, I respect his no matter what the label is that he puts on it. I found that we were brothers, that we loved the same things, and that all of the work and struggle that he has gone through in his life where all of his brothers except one had died in many ways than the fight for independence for Afghanistan, when the Russians were there and various other struggles. All the hard battles that he has fought in his life have not taken his spirit. In fact he viewed them, I think, as a chance to be what he is supposed to be. Those are the battles that a man must fight. He is a man and they are his battles and he fights them. He grieves deeply when he loses someone he loves. I’ve seen that happen.

I saw him when he lost one of his brothers but he overcomes that. He is a man in full and the idea that here he is so different from me and yet we have this brotherhood in common, is one of the clearest examples to me of what it means to have a brother and how important it is, what a rich treasure it is. I was once asked a question about why I make movies about honor and courage and sacrifice. It was a Japanese writer who asked me. I had never been asked a question like that. It was around my first movie, Man in the Iron Mask, and I said, I supposed it’s because the second greatest wealth any man can have in life is to have someone in his life who will die for him, but the greatest wealth you can have is someone in your life you would die for. This Japanese writer said…

The translator translated it, he says that you’re a samurai and when you come to Tokyo he wants to get drunk with you. I think that a man in Japan, a man in Afghanistan and a man in America were all men. When a man is a man, when a man has that attitude of there’s something greater than my own physical survival then you have a brotherhood and you’ve found somebody that will inspire you and that’s what Bob does for me.

Brett McKay: That’s amazing. I think you’re right. I think across cultures men understand that. They understand, when someone says, you need to be a man some people will inevitably fall in the tropes of masculinity, the shallow ones, but I think most men deep down know it means you’ve got to be brave. You have to have a sense of honor. You have to have a sense of love, what you would call fraternity or brotherhood. I think your movies do hit on that. Big time.

Randall Wallace: Brett, what you just said. When we hear in our current culture, you’ve got to be a man, what that often connotes is the opposite of what being a man is. Being a man, when that’s said, I thought it means you’re supposed to ignore pain. You’re supposed to mask off your emotions. You’re supposed to stop being honest. Of course, there are times when we say, I’ve got to man up here, meaning I’ve got to overcome these things but it doesn’t mean let’s ignore them, let’s pretend that we don’t have them. Those men across cultures, I think, what you’re describing here is we’re recognizing in each other that the cost of caring, of loving, of having loyalty and honor, there is a cost and you see in the other man, this is the guy who pays that bill. That’s a man that I want to be like.

Brett McKay: One of the things I love about Braveheart, I think a lot of men love about it, is that, some people call it the manliest chick flick ever made because in the end the movie is about love. It’s about the love of family, the love of country, the love of people, the love of freedom, and it seems like Braveheart is the great encapsulation of this idea that to be a man is to both cultivate hard and soft virtues. How do you think men, not talking about military guys, just everyday guys, can cultivate those braveheart virtues that are both hard and soft?

Randall Wallace: That’s such a great question. I think that on a practical level that we need to be in relationship with each other, with other men, and we need to have relationships with women. I say in the book that a man who does not honor women can never live a braveheart life. It doesn’t mean we have to agree with them or do what women seem to try to get us to do. Look, I’ve been divorced for fifteen years. I can’t claim that I’m an expert in male female relationships but I do believe that women will on the surface be trying to get us to stop being men and yet the last thing they want us to do is to stop being men.

They desperately need us to be men just as we need them to be women and there are differences. Thank God. God made them different. He made us different. For us to revel in those differences is part of the beauty of life. I think that to be a braveheart man means that you face fears rather than run from them. That’s one of the first things. Bravery means being yourself in the face of danger or fear. Sometimes the danger isn’t nearly as great as the fear is and the only way we can find that out is by looking the fear in the face. I had a period in my life, and I still of course have it from time to time, but it was around the time of my divorce when I would get out of bed in the morning and get on my knees and pray with all of my heart for the strength to get through the day with courage and not be dragged down in despair.

That night when I would start to crawl back into bed I’d get down on my knees again to say thank you I got through this day. I realized I did have courage in that day and the only way you can have courage is if there’s something in your life that is dangerous to you. We want to have the opportunity to be courageous and the only way we can do that is by stepping forward into the arena where something is at risk. Our ego, our finances, our physical comfort. That is the only place where courage is required and a brave heart feeds off of courage and courage only exists in the presence of fear. Fear isn’t a bad thing, it’s just a factor. It’s a reality of that dynamic of the presence of courage.

Brett McKay: It seems like, just from our talking, that faith is a really big thing in your life, an important thing. When I was thinking about it last night, about Braveheart, it is in a way not only a story of love. It is a story of faith in a lot of ways that William Wallace had this believe in Scotland that he couldn’t see but he believed in it and he thought it was true and he did all he could to make it work. In a way it is a story of faith. I’m curious, what role does faith fit into Living the Braveheart Life?

Randall Wallace: Brett, I believe that these words that we use, faith, courage, love, hope, are in many ways the same thing. I know we use them in different context and they have different connotations to us but they all mean the same thing, that William Wallace, at least the William Wallace that I wrote. I tell the story in the book that, on the wall of the Air Force academy are the words, they may take our lives but they’ll never take our freedom. The attribution under them is William Wallace. William Wallace didn’t say that. I did.

Brett McKay: He said it now. William Wallace said it now.

Randall Wallace: That’s right. That’s my ego talking. The William Wallace that I wrote loves his country, and I believe that we owe him too by the way. He loved his country so much that he thought, the only way I can help Scotland be free, I can contribute that, I can allow that dream to still breath, is if I am willing to put myself in the hands of people who have already betrayed me. This, of course, does not come from my reading the Encyclopædia Britannica about William Wallace. It comes from my reading the New Testament about Jesus of Nazareth. That is the story that that comes from but I don’t wrap my understanding in a given doctrine or terms. When people will ask me about, say, can a atheist go to heaven? I have these wonderful discussions with various friends of mine, great writers who are even greater friends and some of them call themselves atheists or agnostics or various other forms of religion.

I just tell them, there’s a passage in the Bible, something Jesus said, and I feel absolutely certain that He said it very much exactly as we have it in the Bible, is He tells a parable of, a father says to his two sons, go to work in my field. One son says, I will and he doesn’t and the other son says, I won’t, and he does. Jesus says to the people He’s teaching, which one did the will of his father? I take that in terms of the labels we use for ourselves when we talk about faith. There are people that say, I am a believer but you say, do you do the will of God? There are other people who say, I don’t believe in any of that but you look in their lives and you think they manifest love and faith and courage. I say to myself, I don’t judge. Thank heaven I’m not the person who decides whether somebody is in heaven or not.

I do believe that heaven is here and I think Jesus taught heaven is all around us, but I try not ever to get wrapped up in arguing about labels. I get wrapped up in, are we doing the will of the Spirit that made us, that made the universe? What made the stars made us. I believe we’re made for a purpose. I believe that purpose is love. I believe that courage is one of the manifestations of that. That’s my understanding at the moment.

Brett McKay: Following that will, however you want to describe it, that can be a very scary thing. You get this feeling or this compulsion like this is what I need to do but then all around you have these, no, if I do that I might lose my job.

Randall Wallace: Yes.

Brett McKay: My friends might laugh at me. It can be terrifying at times.

Randall Wallace: Yes. Very early on i made the linkage, if I try something bold, daring, even reckless I will feel better about the results than if I never attempt something like that. I like myself better and I feel more myself when I’m doing something crazy like, I’ll write a screenplay, I’ll write a novel, I’ll write a song. I believe that writing is an act of faith, is an act of courage. I believe what you do is exactly the same. Whenever you speak the very notion that you have something to contribute is certainly an act of courage. Listening is too of course. I think the very fact that we are on this planet, we find ourselves as boys or girls, when we become aware, I’m here. I came from some place. I describe this in the book. I watched a son being born. I’ve seen all my sons being born and shortly after one of them was born I watched my mother breath her last breathe.

You look at a child coming into the world and I cannot witness that without feeling I have just witnessed an overwhelming miracle. When I see someone that I love as dearly as we love our mothers, breathe her last breath and I look at what was once her body and now it looks like a husk I understand why human beings have always grappled with this and had a sense of soul or spirit, have looked for a word, because she was no longer there. Whenever we have that experience, when we find ourselves saying, I am here. I am in this world. I don’t know where I came from. I’m not sure what’s on the other side of this life but, why am I here? You’re either going to behave as if that was a random accident or you’re going to behave as if it’s a gift and you are given it for some reason and it’s not your forever. That’s why I believe every man dies but not not every man really lives. Our whole purpose is to find a way to be really alive.

Brett McKay: We’re going to end on that. That’s a great way to end. Randall Wallace, thank you so much for your time. This has been an absolute pleasure.

Randall Wallace: Brett, thank you so much. Can’t wait to do it again and I will anytime with you buddy. This is wonderful. Thank you.

Brett McKay: Thank you. My guest today is Randall Wallace. He is the author of the book Living the Braveheart Life; Finding the Courage to Follow your Heart. It’s available on amazon.com and book stores everywhere. Go out and get it, it’s a really great read. That wraps up another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice make sure to check The Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoy the podcast I’d really appreciate it if you’d give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. Help us out, giving us some feedback on how we can improve it as well as getting the word out about the podcast. Thanks again for your support and until next time this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.