Maybe you’ve seen the classic Civil Defense film “Duck and Cover†as part of a documentary about the postwar period, a clip of an unintentionally hilarious hygiene film while watching Mystery Science Theater 3000, or a vintage film we ourselves included in a post like this one.

Have you ever wondered where these short instructional films from the 50s and 60s came from?

After World War II, filmmakers pitched a new kind of movie to schools. Films that had formerly been used in classrooms were dull and static – dry lecture dubbed over still shots and documentary-style footage and images. Progressive educators believed that films with more drama, emotion, action, and personality could better capture students’ interest, aiding the learning process and shaping their behavior. The idea took off, and from 1945 until they petered out in the 70s, new studios that were dedicated to the purpose churned out tens of thousands of low budget instructional films that were watched by millions of schoolchildren. Titles ranged from Insects Are Interesting to Learning About Your Nose.

A small subset, about 3%, of this new genre were known as “social guidance†films. Social guidance films had their heyday from about 1945-1960, and were born from filmmakers’ genuine concern for the happiness and well-being of the rising generation. It’s sobering when you think that a fifteen-year-old in 1945 had known nothing but the Great Depression and a World War since their birth. Adults were worried that the young people who had faced such hardship would end up like the Lost Generation that emerged after WWI – cynical, jaded, and amoral. Filmmakers wanted to provide young people with some helpful guidelines that could aid them in socializing, finding happiness, reaching their potential, and becoming involved citizens who were able to navigate an increasingly complex world. The films touted the benefits of responsible, clean-living both for the individual and for society as a whole. Having just won a war by pulling together as a nation, people were highly optimistic about the virtues of civic-mindedness and solidarity.

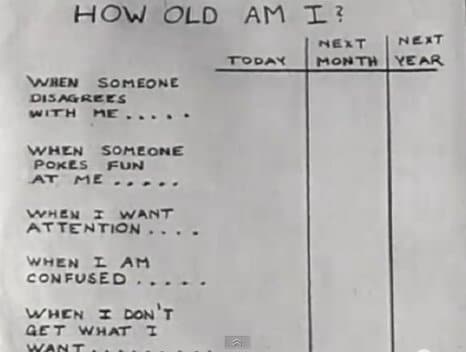

While the films can seem naive, preachy, and conformist (and the ones aimed at girls, sexist) to a modern viewer, they were not made by hand-wringing fuddy-duddies. Their producers were liberals and progressives in their day; it was conservative parents who thought moral instruction should be left to parents and that schools should stick to the three Rs. Instructional filmmakers, on the other hand, thought that “Hollywood-style†films would add needed reinforcement to the advice kids got at home. Each film was made with the guidance of an “educational collaborator:†professors, sociologists, and psychologists who provided input in the hopes of making the advice more “academic” than knee-jerk. The use of charts and graphs was popular.

Interestingly enough, the founder of the most prolific and famous social guidance film studio — Coronet Films — was David Smart, who also created Gentleman’s Quarterly (GQ) and Esquire. Smart was a big believer in the power of instructional films and took the money he made on his magazines and poured it into building the Coronet studio in a suburb outside of Chicago. With two sound stages, the million-dollar studio was the largest east of Hollywood.

Social guidance films might seem hilariously corny today, but their producers sincerely wanted to reach young people who were searching for how to be a good person and live a satisfying life. The films were the first ones to depict everyday life from the teenagers’ point of view, and believe it or not, the producers’ goal was to make them as realistic as possible; the films couldn’t change behavior, they believed, unless the viewer identified with the characters. (We don’t really know how students reacted to them at the time, but their widespread use for a decade suggests they were at least not laughed out of the classroom). Most films begin with a young person facing a dilemma or difficult situation, and over the course of about ten minutes, he learns something new, does some self-analysis on how he can change, and then turns things around for himself; the films were novel in that they showed the characters developing as opposed to being strictly one-dimensional.

By the 1960s, the earnest style of social guidance films no longer fit into the changing culture, and instructional film studios limped into the next decade by producing pieces on driving safety and drugs before shuttering altogether. Some instructional films are owned by modern education companies and live on in university archives, but hundreds were thrown away and are lost forever.

Happily, in the age of YouTube, those that have survived are being given new life by being posted online. Are they sometimes pretty cheesy, unintentionally funny, outdated, and a little slow-moving for our frantic attention spans? You bet. Despite this, I’m an unabashed fan of these old school social guidance films. I appreciate their earnestness in a time of tiresome irony. I appreciate the idea that there is a right and wrong way to do things, and that we all have a role in choosing the former and strengthening society. And I appreciate the idea that nobody learns these kinds of things naturally – they have to be taught, and reinforced as often as possible.

I’ve watched several dozen of these films, and below I offer twelve of my favorites. Twelve films that are worth watching and can impart a few kernels of wisdom if you’re willing to swallow your cynicism for ten minutes and roll with the cheesiness.

PS — Last year AoM experimented with making a modern social guidance film in the retro-style, and hope to make more this year.

Developing Self-Reliance (1951)

Takeaway: “It’s hard work to become self-reliant, but these are the steps: Assume responsibility. Be informed. Know where you are going. Make your own decisions.â€

Snap Out of It! (Emotional Balance) (1951)

Takeaway: “It’s one thing to set high goals for yourself. It’s quite another to be emotionally upset each time you miss your goal.â€

You and Your Work (1948)

Takeaway: “Any job, pounding a plane or selling shoes, is as important as you make it. If you think it’s not important, whatever it is, you’ll soon become bored with it and do it poorly. To enjoy your work, you need to find something more than money. You need personal satisfaction, pride of accomplishment, a sense of importance to others, whether it’s a part-time job after school or a lifetime career.”

The Benefits of Looking Ahead (1950)

Takeaway: “To succeed in something, you have to have a purpose. And make plans for reaching it. And work at it all the time.”

Your Thrift Habits (1948)

Takeaway: “When you want something hard enough, you can find ways to save for it.â€

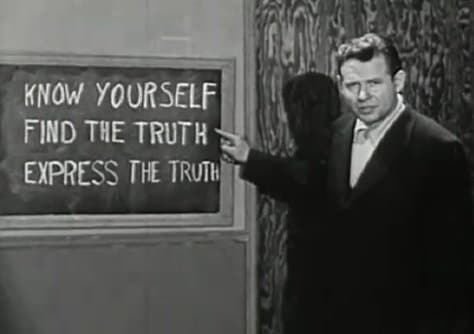

How Honest Are You? (1950)

Takeaway: “When you have a problem involving your own honesty it will help you to remember these three points. Know yourself: be sure of your intentions — the motives behind what you’re doing and saying. Find the truth: test it in the light of past experience and by checking it every way you can. And express the truth: make sure you say what you mean to say and make sure your meaning is clear to your listeners.”

Self-Conscious Guy (1951)

Takeaway: “If I could become skillful, I wouldn’t be so scared of it…I’d forget about myself, and just think of doing it well.â€

How to Keep A Job (1949)

Takeaway: “As long as times are good, there will be jobs for fellas who just barely do enough to get by. But to keep a job when the going gets rough, you need to insure your job — make yourself so valuable your employer can’t let you go.â€

Act Your Age (1949)

Takeaway: “Different parts of our personalities grow at different rates.”

Mind Your Manners (1953)

Takeaway: “Everywhere you go your manners are with you, and they leave their mark. They help you feel sure of yourself too, and they make an impression on people — on everyone you meet.”

What to Do On a Date (1950)

Takeaway: “There are lots of things to do on dates if you know how to look for them, if you plan them with the other person in mind, and if you really try to make sure each date is a good time.â€

Better Use Of Leisure Time (1950)

Takeaway: “A good use of leisure time should give you a change, should help you learn things, and it’s a good idea to have a long-range goal for your leisure time activities.”

Honorable Mentions

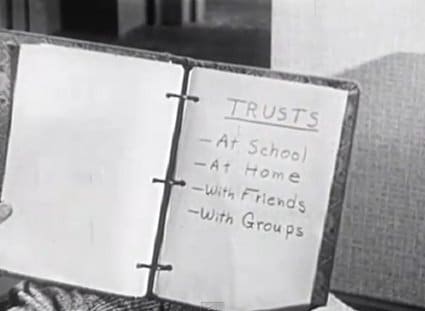

Am I Trustworthy? (1950). Eddie learns that “people have to show they can be trusted with little things, before they can be trusted with big things.â€

Are You Ready for Marriage? (1950). A young couple goes to see a marriage counselor to determine whether they’re ready to get hitched, and he dispenses advice backed by some awesome charts and checklists.

Dating Dos and Donts (1949). A campy Coronet classic.

____________________

Source:

Mental Hygiene: Better Living Through Classroom Films 1945-1970 by Ken Smith