These days, if you’re going car camping or out for a short hike, you’ll likely take with you a daypack — a small bag that holds the gear you’ll need for the outing (camera, snacks, jacket), as well as supplies that are good to have with you in case of an emergency (matches, first aid kit, compass).

A century ago you would have carried something similar, just with less nylon and zippers. When your great-grandpa went exploring the wilderness or marching to battle, he likely carried a ditty bag, haversack, or possibles bag. These handmade pouches held the essentials for frontiersmen and early outdoorsmen, and we thought it would be interesting to take a look at how these bags were used, and what they held inside.

The Ditty Bag

Nessmuk, aka George W. Sears, was a conservationist and writer of the late 19th century. He popularized the pursuit of woodcraft, canoeing, and light camping, and was the first to describe the ditty bag.

The original ditty bags were issued to navy sailors beginning approximately in the early 18th century. Sailors were issued a large canvas sea bag in which to store their spare clothes. Within this sack was placed a smaller pouch which contained a sewing kit, as well as letters from home and souvenirs from their travels. Early seamen were expected to make their own clothes, and thus, as the author of 1884’s Sailor’s Life reports, they knew “how to cut out clothing with as much ease, and producing as correct a fit, as the best tailor.” The origins of the name “ditty” are obscure; it may possibly be traced to a cotton cloth known as ditti; a fabric called dutty which was used to make sails; a take on kitty-bag, itself derived from “kit bag”; or a riff on “ditto” — in reference to the fact the bag contained a spare set of clothes.

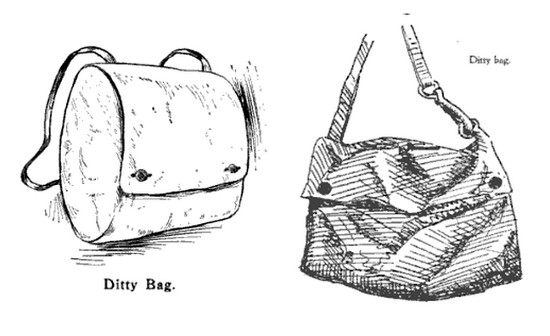

Two illustrations of the ditty bag from the early 1900s.

In the early 20th century, the term ditty bag was adopted by outdoorsmen to describe a small pouch made of canvas, leather, or cloth, that ranged from about 4×6–6×8 inches in size. A 1912 edition of Field & Stream described its “raison d’etre”:

“In camp and when cruising about the woods, there are certain essentials, and many other small articles of constant use, which one should always have handy. They aggregate about two pounds weight and if disposed about one’s clothing will not only make these garments heavy and uncomfortable but will fill them with knobby protuberances which make sitting down or lying down a matter of much struggle and remonstrance…

The ditty-bag has the inestimable advantage of being the place for everything small and loseable — it’s there, nowhere else, and all you have to do is to go and ferret it out instead of having to do the same thing through eighteen or nineteen pockets.”

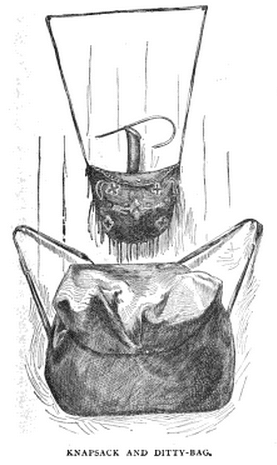

A ditty bag was packed within a knapsack on longer hikes and journeys, and then carried alone for shorter excursions.

An outdoorsman’s ditty bag was kept within his larger backpack when he was hiking, so that little pieces of gear would not get lost at the bottom of the pack. He would then remove it and attach it to a belt, sling it over his shoulder, or wear it around his neck when he ventured away from camp for the day, or even, for the very rugged, several weeks at a time. Its contents served his daily activities and also provided emergency supplies should he become lost or caught in a pickle.

What exactly an outdoorsman packed in his ditty bag came down to personal taste and needs. Field & Stream notes the discussion over the bag’s proper contents represented a “veritable crank’s paradise,” and that “so much individuality of temperament enters that one hesitates to specify anything.” Yet the author does offer his own recommended packing list:

- Compass

- Matchbox

- Saltbox

- Emergency ration (Packed in a tin and consisting of smoked beef and bacon, a packet of tea, bouillon capsules, and hardtack. The tin, when tacked to a stick and held over a fire, doubled as a frying pan.)

- Punkie dope (insect repellent)

- Fisherman’s knife

- Nails

- Tacks

- Needle and thread

- Candle stump

- Razor and piece of strop

- Looking glass (mirror)

- Tube of shaving cream

- Tube of condensed coffee

- Toothbrush and tooth powder

- Fishing supplies (hooks, lines, sinkers)

- Gun cartridges

- Gun grease

- Can opener

- Rifle cleaning rod

The author also recommends bringing, if space allows and one is scientifically-minded, a small field microscope and pair of bird binoculars. Finally, no ditty bag is complete, he argues, unless it includes “one foolish thing which the owner would not be happy without.”

The Haversack

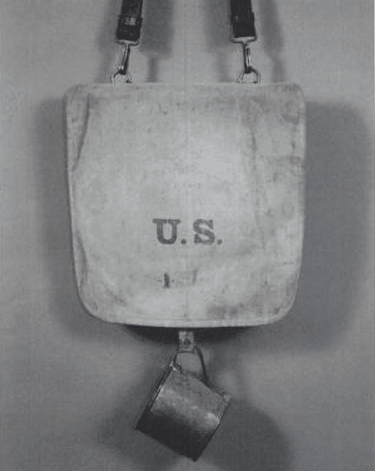

Soldiers of the 19th century carried their haversacks on their right shoulder, their canteen on the left. (You may notice the opposite in these photos; it’s because daguerreotypes are in fact mirror images.)

The haversack functioned a bit like a ditty bag for soldiers. It takes its name from the German word for oats — hafer. At the turn of the 19th century, oats were a staple foodstuff of the poor in Europe, and the British would mix them with water to make a crude bread called oatcake. Workers took these oatcakes or havercakes to their factory jobs for their mid-day meal, and the bag they carried them in became known as a haversack.

Soldiers in the late 19th century would often attach their tin mess cup to a ring on their haversack.

Haversacks were widely adopted by militaries on the march the world over. Usually around 12×12 inches in size, and made from linen or canvas, the bags were slung over the right shoulder (a canteen was slung over the left). They were waterproofed with paint and held a solider’s food and mess utensils, as well as his personal belongings. US infantrymen of the 1800s would typically be carrying about 3 days of rations consisting of hardtack, bacon or salt pork, and coffee. Though the meat was often wrapped in a cotton cloth, having grease leak out and stain and saturate the haversack was a common problem. Another issue was the fact that the paint used to waterproof the bags often flaked off and got on the food.

The contents of an infrantryman’s haversack from the Civil War era: playing cards, utensils, sewing kit, photographs, straight razor. Within the haversack itself, food was kept in a removable cotton pouch, seen on the left.

During the Revolutionary War, innovators began to take a stab at combining the soldier’s haversack and knapsack, so that he didn’t have to carry two separate bags. But the idea was slow to win adoption; the men didn’t like how a combination bag necessitated their carrying around their knapsack all the time when they only needed a small kit, that the knapsack was harder to clean out, and that they couldn’t easily reach into their haversack to nibble on their rations while on the march.

The Possibles Bag

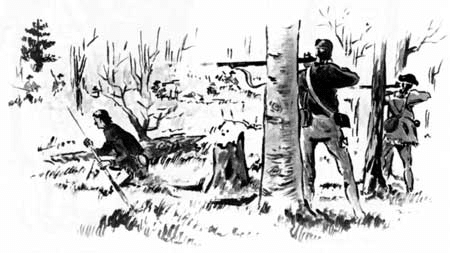

In the 18th and 19th centuries, mountain men, minutemen, frontiersmen, and black powder hunters of all kinds would usually be found with two bags slung across their shoulders: their powder horn and their “possibles bag.” It was so-named either because it contained everything you might possibly need for the day, or because you could possibly find most anything packed in the bag. As with the ditty bag, the contents of a man’s possibles bag varied by taste and necessity.

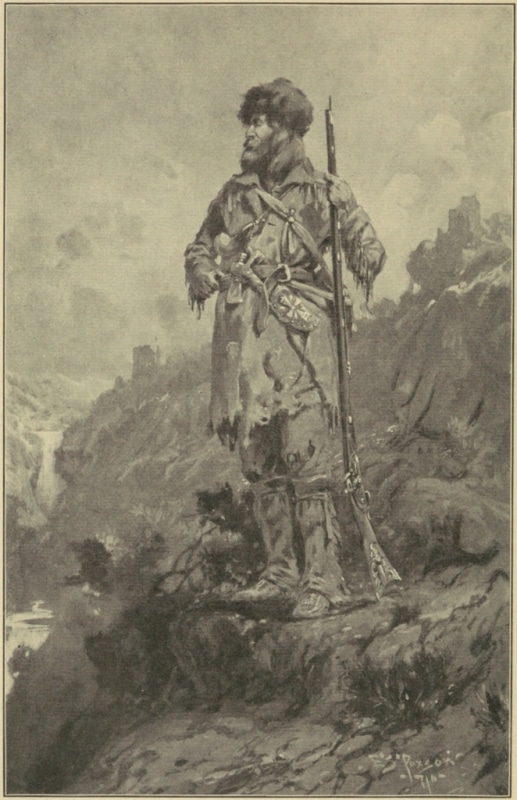

Davy Crockett, rocking a possibles bag.

Most typically, the frontiersman’s possibles bag was stocked with all kinds of essentials for hunting, fighting, and venturing through the great outdoors: tobacco and pipe, tin cup, flints, jerky and other edibles, nipple wrenches and picks (tools for one’s muzzleloader), etc. Within the possibles bag might also be a “strike-a-light” pouch, which held a fire striker and tinder. The bags were made of animal skin, and either slung over the shoulder or attached to a belt.

The very notion of a possibles bag is quite evocative in and of itself, and in the midst of the research for this post, I came across a nice story of a father who found a way to carry its spirit into the modern day. When author Robert Fulghum’s son graduated from college, he gave him a possibles bag as a symbol not only of the opportunities before him, but the oldtime frontiersman’s spirit of improvisation:

“Many [pioneers] survived even when all these items were lost or stolen. Because their real possibles were contained in a skin bag carried just behind the eyeballs. The lore of the wilderness won by experience, imagination, courage, dreams, and self-confidence. These were the essentials that armed them when all else failed.

I gave my son a replica of the frontiersmen’s possibles bag to remind him of this attitude. In a sheepskin sack I placed flint and steel and tinder, that he might make his own fire when necessary; a Swiss Army knife — the biggest one with the most tools; a small lacquer box that contained a wishbone I saved from a Thanksgiving turkey — for luck; a small velvet pouch containing a tiny bronze statue of Buddha; a Cuban cigar in an aluminum tube; and a miniature bottle of Wild Turkey whiskey in case he wants to bite a snake or vice versa. Invisible in the possibles bag were his father’s hopes and his father’s blessing. The idea of the possibles bag was the real gift. He will add his own possibles to what I’ve given him.”

Do you carry a possibles bag or other kind of daypack either when camping or in your everyday life? What do you pack in it?