In this 3-part series on the ax, we’ve talked about the tool’s history and anatomy, and how to choose the right one for your needs. Today we’ll conclude the series by offering a primer on how to use your ax safely and effectively.

How to Swing an Ax

Preparing for Chopping

Clear your swinging/chopping area. Before you start swinging your ax, you’ll want to prepare your chopping area. You need plenty of room to swing an ax, and you don’t want anything (not even a twig) to get in the way of your swing, as it can cause you to miss your mark, or deflect the ax into your own body. So remember this maxim: “Clear the ground an ax-length’s around.†An “ax-length†means the length of the handle plus the length of your arm. “Around†means overhead and underneath, in front and back, and on both sides. To check that you’ve got this clearance, hold your ax by the head and slowly swing it in all directions. Remove any branches or brush that touch the handle.

Besides clearing the path for your ax’s swing, clear the ground of any roots or loose rocks that you could stumble or slip on. And make sure no one’s standing too close to you: “Onlookers stay two ax-lengths away.â€

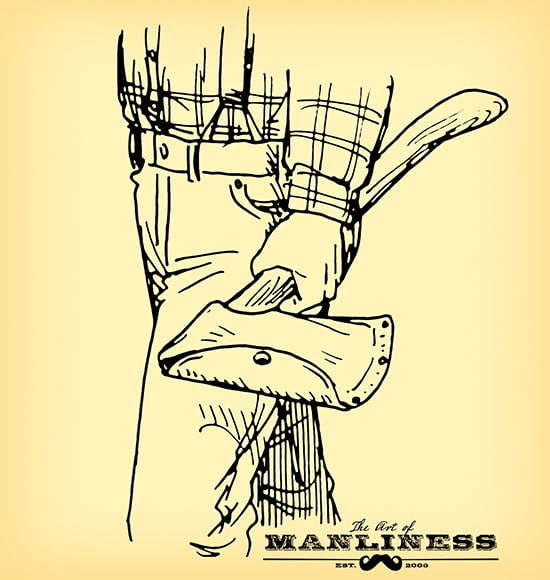

Hold the ax properly. If you’re right-handed, hold the ax so that your left hand sits just above the knob at the end of the handle, palm facing towards you. Your right hand should grasp the neck a few inches below the ax’s head, with its palm facing away. If you’re a lefty, just reverse the instructions.

Hold the ax with a grip that’s firm but not tense. When you swing at your target, your top hand will slide down to the bottom, so that your two hands meet.

Focus on accuracy first, not power. It won’t do any good to swing an ax as hard as you can if it hits in completely different spots every single time. You’ll cut more wood much more quickly and efficiently if you hit the wood in about the same spot every time you strike it. So focus on accuracy first; keep your eyes trained on the spot you want to hit, and concentrate on keeping your aim true and using controlled strokes. Once you get accurate with swinging an ax, then you can add in speed and power.

Swinging the Ax

Lateral Swings

Lateral chops are rarely true horizontals and usually more like diagonal swings going from the top down. You primarily use a lateral swing to fell a tree.

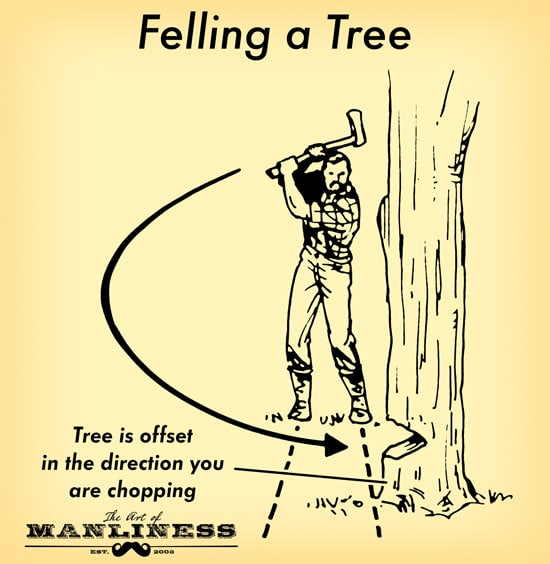

Felling a tree. When striking a tree laterally, set-up is key. For maximum power and safety, follow this rule set out in The Ax Book: “For all sideways or diagonal chopping strokes, strike only at targets lying past your front in the direction of chopping.†This is to say, rather than standing directly in front of the tree you’re chopping, you want to offset yourself so that the tree is in front of your lead foot (your left foot if you’re right-handed). Setting yourself up this way will put your target (the tree) “past your front†in the direction of your chopping. This position will allow you to follow through on your swing, but also reduce the chances of injuring yourself if the ax head ricochets off the tree when you strike.

We’ve previously gone into detail about how to fell a tree with a chainsaw, and the same basic principles apply to doing it with an ax. Felling a tree with an ax, however, is more difficult and dangerous because you lack the precision with your cut that you can achieve with a chainsaw.

Just like with using a chainsaw, you’ll make an initial 45-degree face cut on the side of the tree that faces the direction you want it to fall. The difference between felling a tree with an axe comes in how you do the back cut. Instead of making the back cut perfectly perpendicular to the tree like you would with a chainsaw, you’re going to make another 45-degree cut with your ax on the opposite side and two inches above your face cut. This will create a hinge and if everything goes to plan, the tree will begin to fall down in the direction of your face cut.

Vertical Swings

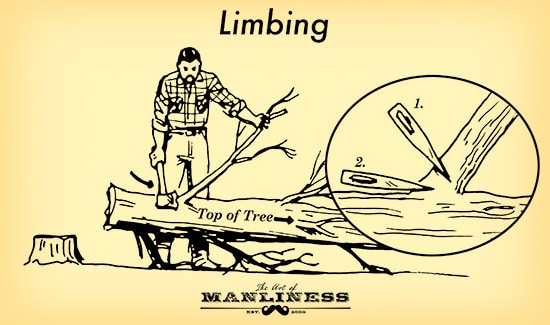

Vertical chops are those that go up and down. You use vertical swings when limbing, bucking, and splitting wood.

For small branches you can lop them off with one stroke to the base; for medium-to-large branches, make 2 cuts — first at an angle, and then at the branch’s base, parallel to the tree.

Limbing. Limbing is when you remove the branches from a felled tree. Remove the limbs on top of the downed tree first, so that when you remove the bottom limbs, if the tree falls or moves, the top branches won’t flail about and scratch or impale you. Stand on the opposite side of the trunk from where you’re cutting and always chop limbs off in the direction of the top of the tree; do not cut into the “crotch†of the limb.

For medium- to large-sized limbs, aim to remove them with two strokes. Land the first at an angle a few inches up from its base. This will loosen its resistance on the tree. Then do a second stroke that’s parallel to the tree and aimed at the limb’s base. For smaller limbs, you can shear them off with one stroke: cut sharply into the base at a slight downward angle, rather than parallel to the tree.

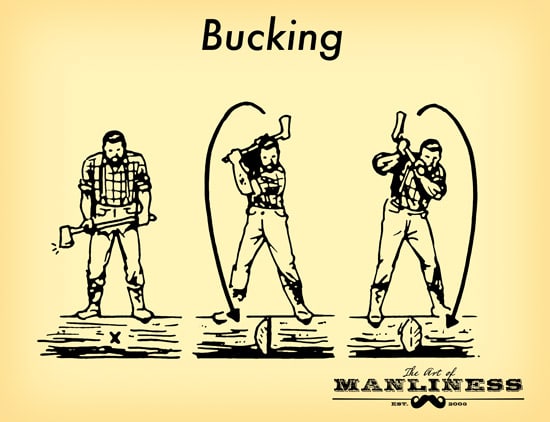

Bucking. If you’ve felled a tree, you’ll need to buck it into smaller, more manageable logs. To do this with an ax, stand on top of the log you wish to buck, with your feet a bit wider than shoulder-width apart. You’re going to chop a “V†shaped notch in the part of the log between your legs, chopping halfway into one side, and halfway into the other. You want the kerf, or the cut you’re making, to be as wide as the tree is thick; aim for an angle of cut about 45 degrees.

Bring the ax above your right shoulder and swing it down between your legs. Continue until you cut the right side of the notch out. Turn your body to the left and chop the left side of the “Vâ€-shaped notch out. Once you’ve created a V-shape on one half of the log, turn around and chop another V on the other side of the log until the two notches meet.

Splitting. It’s not recommended that you split logs with the same ax you use for felling; a splitting maul is more appropriate for the job. We’ve covered how to split wood previously.

You can also split small sticks and dead branches into small kindling with an ax, though again it’s not the best tool for the task — a hatchet is. Whether you use a hatchet or ax, you ideally want to split loose wood on some solid surface. In trying to split small wood on the ground, you may miss, driving the ax head into the ground, where it can become damaged by grit or rocks.

So if you need to split a stick, place it on a solid, sufficiently broad log or stump. Having something to back it will protect the ax at the finish of the stroke.

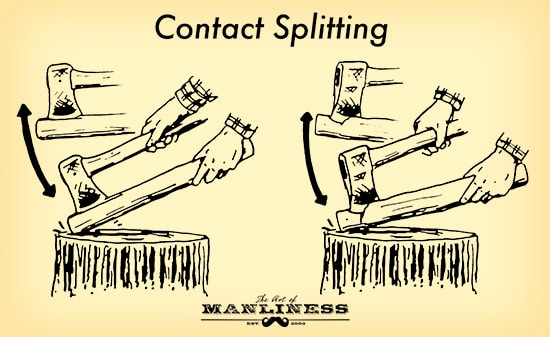

For small sticks, it’s actually easier, faster, and safer not to swing at them at all, but rather to split it using the “contact†method. To split a stick down the middle, wedge the ax’s bit into its center, and then bring the wood and ax down together on your chopping block. Twist the wood some if needed and it will usually split apart. To chop a stick in two, set the bit on a slant across its grain. Raise the stick and ax together and bring them down onto the block.

How to Handle an Ax Safely When Not in Use

Muzzle the blade. A properly sharpened ax can easily slice through clothing and body tissue, which is why you need to take great care when swinging one. But that circumscription must also carry over to when you’re not using your ax. As outdoorsman Bernard Mason writes in his book Woodsmanship, unsheathed axes have a tendency to “bite.†That is, axes find a way to cut or nick people even when they’re lying inert on the ground — folks can accidentally kick the ax or fall on it.

To prevent these ax bites, always “muzzle†your ax when you’re not using it by putting on its sheath.

If your sheath isn’t handy, take the following precautions to ensure that your ax doesn’t jump up and bite someone while you’re not using it:

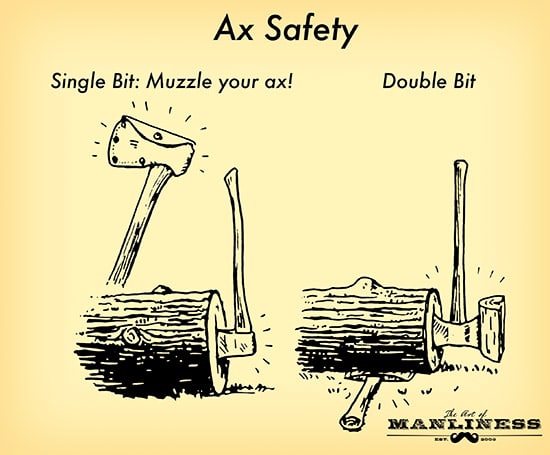

If it’s a single-bitted ax, stick the cutting edge into a log. Never lay it down on the ground or lean it against a tree.

If it’s a double-bitted ax, sticking one cutting edge into a log still leaves another cutting edge exposed. To remedy that, drive one bit into a small piece of wood before you stick the other bit into the log. Better yet, lay the ax on the ground, but place the head under the log so that both cutting edges are hidden.

Hold the ax pointing down and away from you while walking. When you walk with your ax, it’s tempting to throw it over your shoulder like you’d imagine an old-time lumberjack would do. But that’s not the safest way to carry an ax; if you trip, you could fall into the ax’s blade, and if it’s an unsheathed double bit, the blade could cut into your back. Instead, you’ll want to ideally sheathe your ax and then grip it just beneath the head with the bit pointed outward. If you stumble, toss the ax away from you and other people.

Hand someone an ax with care. When handing someone an ax, hold it by the handle, with the head hanging down vertically. Wait until the other fellow has a firm grip on the handle before you release yours.

How to Take Care of Your Ax

With proper care, an ax can last for generations. To ensure that your grandson is using your ax when you’re long gone, observe the following guidelines:

Keep your ax sheathed and indoors when not using it. Don’t leave your ax outside and exposed to the elements. Moisture will cause the ax head to rust and the wooden handle to warp. When you’re done with your ax, store it in a dry place like your garage or shed.

Keep your ax sharp. As old Abe Lincoln said, “Give me six hours to chop down a tree and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe.†A sharp ax is an effective and safe ax. See our post on how to sharpen bladed tools for instructions on sharpening.

Never use an ax as a hammer. While the poll/butt end of an ax head makes for a convenient and tempting hammer, you always want to use the right tool for the right job. An ax is not a hammer and shouldn’t be used for driving in nails or stakes.

Don’t chop with a cold ax. If you’re chopping in cold weather, warm the ax head a bit by the fire before you get started. Striking a cold steel ax head can cause it to chip or even shatter. When warming the ax head by the fire, don’t get it too hot — fire takes the temper (hardness) out of steel. It’s warm enough if you can still touch the ax head with your hand.

Series Conclusion

Our pioneer forebearers relied on 3 main tools: the knife, the gun, and the ax. Of these, the ax was arguably the most important. An ax is a uniquely versatile tool; with it you can fell trees to make shelter or a raft, split firewood to keep your warm, and make parts to construct other tools and utensils. And of course it can be used as a deadly weapon as well. If you were stuck on an desert island or forced to navigate the apocalypse, and could only choose one tool, you’d be well-served by selecting the ax.

In these easier and more civilized times, the ax isn’t as central to most men’s lives, but it can still be a trusty tool to store in your woodshed and take along on outdoor adventures.

So keep those axes sharp and stay manly!

Read the Series

History, Types, and Anatomy of the Ax

How to Choose the Right Ax for You

How to Use an Ax Safely and Effectively

_____________________

Sources:

Illustrations by Ted Slampyak