Pick up any health magazine or visit any wellness website and you’re bound to see headlines like:

“10 Ways to Eliminate Stress!”

“How Stress Is Killing You (and Your Sex Drive!)”

“25 Secrets for a Stress Free Work Day!”

And if you were to catalog modern consumer goods, you’d find that many are designed to reduce stress and increase comfort: central heating and air conditioning so you’re always just the right temperature; mattresses that allow you to adjust their firmness to your exact personal preference; convenience food that ensures you never have to be even a teeny bit hungry.

We click on these headlines and buy these products because as everyone knows, stress is bad: it makes you fat, weakens your immune system, and leads to heart attacks. It’s also just plain uncomfortable – something we should avoid whenever we can. Right?

But what if much of that common wisdom is wrong? What if our constant striving to eliminate stress is actually doing us more harm than good? What if stress in certain amounts actually makes us stronger and healthier?

Research from the past few decades suggests that this counterintuitive idea is in fact the case. Today I’ll explain why, and show you how voluntarily and intentionally subjecting yourself to a little bit of stress can make you a better, stronger, and more resilient man.

A Background On Stress

Most people associate stress with threatening or anxiety-producing situations that elicit a strong fight-or-flight response, like rushing to meet a deadline, working up the nerve to give a public speech, or encountering a grizzly bear. But from a physiological standpoint, stress is simply your body’s reaction to circumstances in which it feels it needs more strength, stamina, and alertness in order to survive and thrive. Any perceived challenge or threat to your well-being can induce a stress response, which is your body’s attempt to adapt to the demand and bring your physiological and psychological systems back to normal.

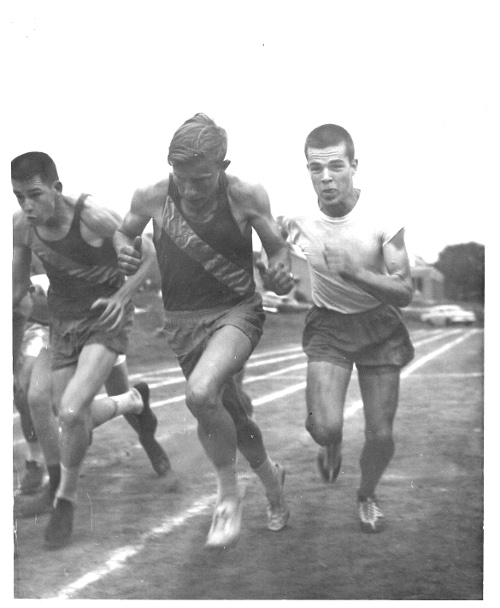

Thus, a stress response can be activated by things like taking an exam or being held up at gunpoint, but also by stimuli like allergens, bacteria, lack of sleep, hunger, cold, and heat. “Good” things like asking a girl out on a date or standing at the starting line of a race can be stressors too. Even something as healthy as exercise is a stressor (“stressing” your muscles and cardiovascular system is essentially how you get stronger and fitter).

As you can see, the stress response can be set off by things both big and small, and it can be the result of both positive and negative circumstances. And not only can the situations that spark stress be positive, but the stress response itself can actually be quite desirable.

What Happens When We Experience Stress?

An important thing to keep in mind about stressors is that while they can be different in form, they all produce the same generalized stress response in varying degrees.

When you experience a stressor, your nervous system responds by releasing the hormones adrenaline, noradrenaline, and cortisol into your bloodstream. These hormones get you revved up and ready for action: your heart rate, blood pressure, sweating, and breathing increase; your blood vessels dilate to speed blood flow to your muscles; your pupils dilate to enhance your vision; and your liver releases stored glucose for your body to use as energy.

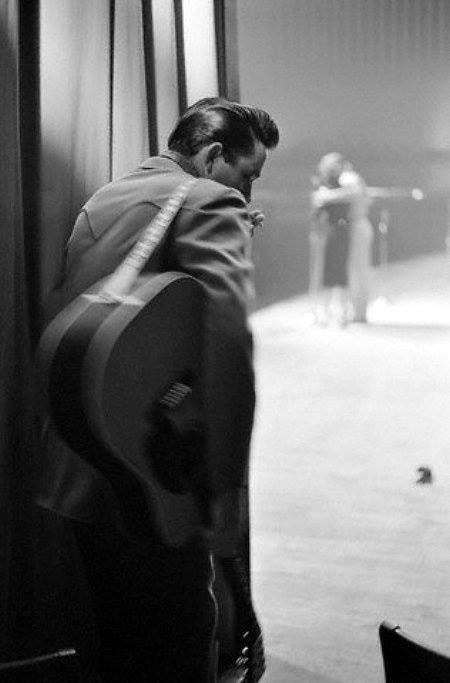

In the face of a challenge – a job interview, an important game, a difficult test – the stress response puts you on your toes and can improve your performance and ability to handle pressure. It also lends excitement to life: when you feel nervous before giving a big speech, or getting on a roller coaster, that’s stress too. It’s for this reason that neuroscientist John Coates argues that “the stress response is such a healthy part of our lives that we should stop calling it stress at all and call it, say, the challenge response.”

I love this idea. Instead of seeing it as a negative, imagine stress as the power to tackle hard things and come out on top. But like any power, it can be harnessed for productive ends or mishandled in ways that have destructive results.

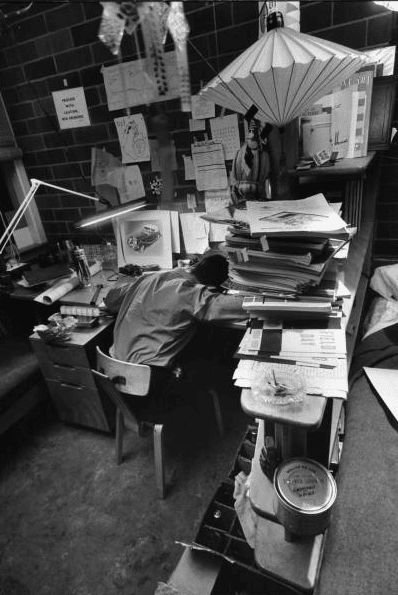

When Does Stress Become a Problem?

Stress becomes a burden rather than a boon in the face of two main factors:

The first is stress overload. The amount of stress you feel given a certain set of circumstances is directly proportional to the degree in which you feel your skills and resources (including time) are adequate in addressing them. This state of competence can be based on either reality or one’s own optimistically or pessimistically rendered self-assessment. A man who enjoys and is talented at public speaking will feel much less stress before making a presentation than a man who is shy and speaks awkwardly. A man who is much less confident in dating and what he has to offer women will feel much more devastated when a girl dumps him than a man who has little doubt he’ll soon meet someone else.

Instead of getting us revved up for action, stress that seems too big to handle can feel crushing, leaving us feeling overwhelmed and too paralyzed to do anything at all.

Stress also becomes a problem when the set of circumstances causing it becomes chronic. The stress response was originally designed to help humans deal with immediate threats and challenges – after the adrenaline rush, our nervous systems quickly returned to stand-by mode in preparation for the next challenge. Saber-toothed tiger! Throw spear! Tiger dead! Whoo, relax time. Me go back to cave painting. But in modern times, our stressors can go on and on and on. As much as we might like to, we can’t spear the annoying guy on Twitter or a grating co-worker. Instead, we have to put up with him day after day. And day after day, this chronic stress causes our bodies to dump out low levels of stress hormones. Unfortunately, a steady dose of something that was supposed to be rare and fleeting can make us physically and emotionally sick.

Here’s the bottom line: stress isn’t a bug, it’s a feature in our body’s programming. It’s just that we’ve evolved to experience it in moderate amounts for short periods of time that are followed by a resting period in which we can recoup, calm down, and rejuvenate. Too much stress for too long is what turns stress from a positive health-booster to a negative health-sapper.

How the Generalized Stress Response Boosts Health and Performance

Instead of thinking of stress as wholly bad, see it as a tool you can use to boost your health, strength, toughness, and mental acuity. Besides priming our bodies and minds to take on an immediate challenge, the generalized stress response also provides, when used wisely, several other lasting benefits.

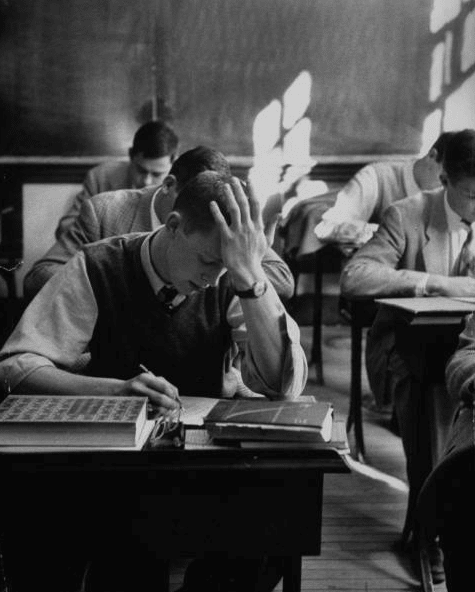

Stress May Cause Cell Growth in the Learning Centers of the Brain

In a 2013 UC Berkley study, researchers found that adult rats that experienced moderate amounts of stress for a brief period showed increased growth of neural stem cells in their hippocampus, an important learning center of the brain. Other research suggests that rats experiencing brief bouts of stress over a period of time showed increases in the brain’s level of a chemical called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF helps increase neuron growth in the parts of the brain responsible for memory and other learning skills. Overall, these studies suggest that brief bouts of moderate stress may enhance learning ability.

Stress May Be Correlated With Longevity (Depending on Your Perspective of It)

We typically think of stressed-out folks as unhealthy and more likely to have a reduced life span. But recent research suggests that increased amounts of stress may be correlated with a longer life. It just depends on whether you view stress as a positive or a negative in your life.

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison asked over 29,000 people to rate their level of stress over the past year as well as whether they believed stress is harmful to their health. Over the next eight years, the researchers checked public death records to see which of the respondents died.

People who had initially reported that they had experienced a lot of stress the previous year had a 43% increased risk of death. But that was only true for the people who also believed that stress is harmful for your health.

Here’s where things get interesting. People who had reported high levels of stress but believed that stress wasn’t harmful to your health were amongst the least likely to die as compared to all other participants in the study, even the people who had experienced very little stress.

So stress isn’t what kills us, it’s just thinking that it can kill us that kills us. In fact, this research suggests acute bouts of stress followed by periods of rest – as nature intended us to experience stress – may play a part in helping us live longer. The key to getting that benefit is to simply think of your stress response as your friend. It’s your body’s way of getting ready to take on a challenge and be awesome.

Moderate Amounts of Stress May Strengthen Your Immunity

When we experience chronic stress overload, immune function is compromised and we’re more vulnerable to getting sick. But recent research suggests that when we experience moderate amounts of stress in short bouts followed by a period of recovery, our immune system actually gets stronger.

In one Stanford University study, researchers introduced stress to a bunch of rats by injecting them with hormones and restraining them for a period of two minutes to two hours. Researchers then tested their blood and found that there was a massive redistribution of immune cells to vulnerable areas in the body after the rats experienced a stressor.

Research hasn’t been done yet to see if this stress-induced immune boost is long lasting. Anecdotally, I can report that ever since I started exercising regularly (a form of moderate, short-lived stress) I haven’t gotten sick as much as I did when I was a couch bum.

Stress Improves Performance Across a Spectrum of Activities

If you want to perform at your best, whether on a test or on the job, you need a bit of stress. The Inverted-U Hypothesis proposes that increases in stress typically are accompanied by increases in quality of performance… only up to a point, though. After you reach a certain threshold, you experience diminishing returns where rising stress results in deteriorating performance quality in certain tasks.

Several sports performance researchers during the 1970s and 1980s found that athletes experienced increases and decreases in different motor skills at different stress-induced heart rates. For example, when heart rates reach above 115 beats per minute (BPM), fine motor skills like writing begin to deteriorate. However, when heart rates are between 115 and 145 BPM, complex motor skills like throwing a football or aiming a gun are at their peak.

Cognitive functioning is also at its peak in this range. After 145 BPM, performance for complex motor skills begins to diminish, but gross motor skills like running and lifting remain at optimal levels. When heart rates go above 175 BPM, capacity for all skilled tasks disintegrates and individuals begin to experience cognitive and physical breakdown.

While most of the research on stress and performance has been used in the realm of sports, researchers believe the Inverted-U Hypothesis applies to other areas like work and school as well.

Stress Increases Physical Strength and Psychological Resilience

“Flee luxury, flee enfeebling good fortune, from which men’s minds grow sodden, and if nothing intervenes to remind them of the common lot, they sink, as it were, into the stupor of unending drunkenness. The man who has always had glazed windows to shield him from a drought, whose feet have been kept warm by hot applications renewed from time to time, whose dining halls have been tempered by hot air passing beneath the floor and circulating round the walls — this man will run great risk if he is brushed by a gentle breeze…The staunchest member of the body is the one that is kept in constant use…So the bodies of sailors are hardy from buffeting the sea, the hands of farmers are callous, the soldier’s muscles have the strength to hurl weapons, and the legs of a runner are nimble. In each, his staunchest member is the one that he has exercised.” -Seneca

Physical exercise is essentially a form of stress: when you lift weights, you create tiny tears in your muscles. When your body repairs these tears, the muscle grows stronger.

The same mechanism applies less literally to strengthening our mental and emotional resilience. Stoic philosophers in ancient Greece used to purposefully do exercises that would induce the stress response – taking cold baths, courting public humiliation, fasting – in order to build their psychological toughness. They believed – and I have found this to be true in my own life – that by intentionally and regularly tackling smaller challenges, they would be well prepared to handle larger challenges that arose with calmness and confidence.

The Philosophy of Hormetism: Tapping Into the Unique Benefits of Particular Stressors

While all stressors cause the same general stress response, different stressors have unique effects on the mind and body. For example, while both extreme cold and heat exposure will cause the generalized stress response, a cold shower will also have different specific effects than sitting in a hot sauna.

Philosopher and chemical engineer Todd Becker runs a blog dedicated to exploring the research behind the specific effects of different stressors. It’s called Getting Stronger and I highly recommend you check it out. From his research, Mr. Becker has developed a philosophy he calls “Hormetism.” Hormetism is based on the biological phenomenon of hormesis, whereby a beneficial effect (improved health, stress tolerance, growth, or longevity) results from exposure to low doses of an agent that is otherwise toxic or lethal (like stress) when given at higher doses.

A perfect example of the hormetic response is seen in vaccinations. We’re given a low dose of an otherwise harmful virus and our immune system becomes strong enough to withstand full-blown exposure to that virus later on in life.

But the hormetic response isn’t just limited to vaccinations. As Mr. Becker has cataloged, scientists have found the hormetic response across a wide spectrum of agents including cold and heat exposure, intermittent fasting, radiation exposure, and even blood loss.

I plan on dedicating full blog posts to the hormetic response that each of the above stressors provide (and how to incorporate them into your life in a healthy way), but today I want to give you a taste of some of the specific benefits that can accrue from voluntarily and judiciously exposing yourself to certain stressors.

Cold Exposure (we covered a lot of these benefits in our post on cold showers, but below is a quick summary)

- Improves circulation

- Relieves depression

- Burns fat

- Strengthens immunity

- Boosts mental and emotional resilience

Heat Exposure

- May Increases longevity

- Increases cellular function in parts of the brain responsible for learning

- Boosts physical endurance

- Quickens recovery

- Improves insulin sensitivity

- Releases human growth hormone

Intermittent Fasting

- May increase longevity

- Improves insulin sensitivity

- Releases human growth hormone

- Improves cardiovascular risk markers

- Increases neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, which aids in learning

- Calorie reduction may help slow cancer proliferation

- Aids in cellular cleaning (autophagy), which is important to overall health

Sunlight

- UV rays spur the conversion of cholesterol to vitamin D in our body

- Brief bouts of sun exposure may actually reduce some types of cancer

Blood Loss

This one is a bit more controversial, but losing a bit of blood every now and then in the form of blood donations might actually provide a bunch of health benefits. It all comes down to reducing the amount of iron in our system. For more information about this, see Survival of the Sickest.

- Increases longevity

- Increases immune function

Conclusion

Contrary to popular belief, stress can be a healthy part of our lives. By harnessing stress in the way nature intended – in moderate doses, administered in short bouts, and looked at from the right perspective – it can be a potent power that helps us become our best and rise to life’s challenges. So instead of always looking for ways to eliminate stress, find more ways to intentionally and positively incorporate it into your life by stepping off the path of comfort and ease from time to time and embracing “The Hard Way.”