Editor’s Note: This is a guest article by Marine Corps veteran and paramedic Charles Patterson.

Author’s Note: Given the nature of impalements and the number of variables that cannot be accounted for in one article, many of the treatment options will require a caveat of “depending on (x) or (y).” In every situation, common sense must be applied with extreme prejudice towards seeking help from medical professionals rather than attempting to correct or treat an impalement on your own. However, some situations occur far beyond the reach or support of emergency medical treatment. Receiving further training in multiple areas of survival and preparedness is essential for a positive outcome. Your level of training and preparedness and your distance from or ability to contact emergency care providers can mean the difference between full recovery, mere survival, or death. Be smart, be prepared, and live strenuously.

Impalement injuries happen when the body is penetrated by the forceful impact of what is typically an elongated, solid object. This force can be generated by the person themselves, as when a person falls from a height onto a spiked iron fence, or the force can be generated by an external source, as when the debris/shrapnel from a strong wind or explosion is propelled into the body.

With this kind of injury, an object with which someone has been impaled remains embedded. A bullet fired from a gun would not be considered an impalement, whereas a stab wound from a knife, with the knife remaining in place, would. An impaled object may be visible with some portion remaining outside the body, or it may be concealed and entirely embedded in the tissue. These embedded items are more commonly referred to as foreign bodies and are not the focus of this article.

While being a relatively rare occurrence, impaled objects present unique challenges for patients, first responders, and hospital staff (and make for some gnarly-looking x-rays). Individual management of an impaled object varies widely based on the size, shape, and material of the item, whether fixed or free, the area of the body that’s impaled, the cause of the impalement, etc.

Regardless of the many variables, however, an impaled object’s essential management is almost universally the same. And in all but the most minor instances of trauma involving an impaled object, emergency medical services should be immediately activated, if possible, or contacted at the earliest opportunity. Here’s what to do until you can reach/be reached by professional medical care.

How to Treat an Impalement Injury

Do Not Remove the Object!

You’ve probably heard this before, and it is the fundamental element of managing an impaled object. Leave the object in place! Depending on the size, shape, velocity, and area of impact of the object, it is likely that one or more blood vessels have been severed or internal organs penetrated. The object, left in its place, fills the hole that is created and can limit hemorrhage. When the object is removed, this void is no longer filled, and immediate, massive hemorrhaging can occur, internally and externally, quickly leading to shock and death. While external bleeding can be relatively simple enough to control, internal bleeding cannot (outside of an operating room) and is of particular concern. Depending on its shape and size, removing the object may also damage the affected tissue beyond simple blood loss.

Expose the Wound Site

Cut off clothing and any gear to expose the wound site. Don’t try to manually remove clothing or equipment and risk causing further injury by incidentally manipulating the object. Instead, cut their clothing with trauma shears, use a pocket knife, rip things open Superman-style — whatever you need to do to expose some skin. You can’t treat a wound if you can’t see a wound. Don’t be shy; you can always cover the victim back up later.

If the impaled object is a knife, or another object resulting from an attack, take care not to cut through the hole created by the object, if possible. The clothing may be entered into evidence, and cutting through that hole can ruin the integrity of the evidence. If it’s an attack from the reincarnation of Vlad the Impaler, it’s already too late for you. Don’t worry about evidence.

Reduce Object to a Manageable Size

It may be necessary to reduce the object’s size to a length that is more manageable for stabilizing the object and transporting the patient. A longer object can be difficult to stabilize and can cause more damage to the injury site since it has more leverage than a smaller object.

It is not always necessary to shorten the object. This is an example of a situation that requires some common sense and exercise of good judgment, as there isn’t a specific rule on when to leave it or reduce the size. In most instances, this should be done by a team of emergency medical providers and with the utmost care to prevent further injury to the patient. Clipping off part of an arrow after a bow-hunting accident could potentially be done if you’ve got a ways to go before reaching professional care.

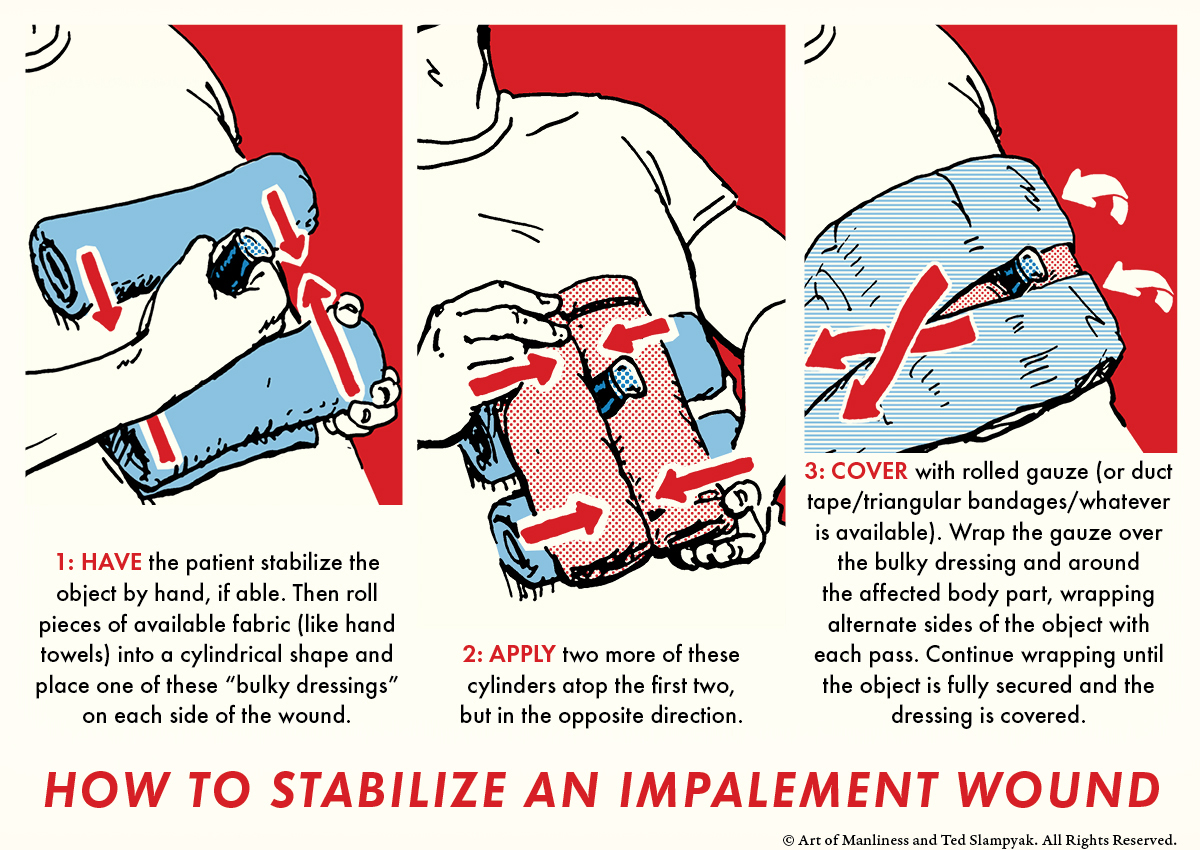

Stabilize the Object and Control Bleeding

The object needs to be stabilized to prevent further injury. Again, “depending on . . .,” this may be as easy as applying a “bulky dressing” (a thick pad or compress) around the object and securing it with rolled gauze, triangular bandage, or similar. Depending on the object’s size, a bulky dressing may require a lot of material, and in some circumstances you may have to get creative. If the object is visible through both sides of the affected area (e.g., it goes in one side of the leg and out the other), stabilize the object on both sides. Bleeding can be controlled with pressure and may be achieved by the bulky dressing applied for stabilization.

To illustrate our goal in applying the bulky dressing, hold a pen or pencil tightly in your fist with only an inch or two of the pen enclosed inside your hand. Move the end of the exposed pen and notice how much it can be moved, despite a tight grip. Now place fully 2/3 or more of the pen in your fist. Notice how much more difficult it is to move and how much less movement occurs. Our goal is to create a dressing that can prevent the object from moving, just as holding more of the pen results in less movement.

Treating Various Body Parts for an Impalement Injury

Eye

If the impaled object is in the eye, take great care not to apply pressure to the eye. Apply a bulky dressing around the object, and cover both eyes. Our eyes track together, so if the right eye is impaled and the left eye can look around, the right eye will move with it. The goal is to prevent unnecessary movement, so both eyes must be covered. In this situation, staying calm and reassuring the patient is vital since you have just removed their eyesight. Another option is to use a small styrofoam cup (if you happen to have one handy) with a hole the object’s size cut through the bottom. Place the cup’s mouth over the eye, and feed the object through the hole in the bottom. Use rolled gauze or anything you have on hand to secure the cup on the injured eye and cover the other unaffected eye.

Head and Neck

While rare, impaled objects in the head and neck have very high mortality rates for obvious reasons. A solid object being forced into the skull and brain tissue isn’t exactly friendly to life. And the neck — with critical formations including the spinal cord, multiple large blood vessels, esophagus, and my personal favorite, the airway — doesn’t like to be disrupted either.

But despite a high chance of death, there are several unbelievable stories of objects impaled in just the right way, even into the brain, that were carefully extracted with no permanent damage to the patient. Stabilize the item in the head with bulky dressing, secure it with circumferential wrap, and be very, very careful not to move it.

For the neck, securing a dressing with tape is the best idea. Never wrap bandaging circumferentially around the neck. An impaled object in the neck will most assuredly require advanced airway management by medical providers. Controlling bleeding and stabilizing the object is your goal. Since the neck has a lot of soft tissue and muscle, assist the patient in keeping their head still to minimize neck movement.

Chest and Abdomen

Like the neck, the chest and abdomen contain vital structures (just about every one of our all-important internal organs). The danger of moving or removing the object cannot be overstated.

For a chest injury, the main concern is impalement of lungs and heart, and major vessels leading to and from the heart. Even if the heart has been pierced, it is possible for the patient to survive with quick intervention and transport to a trauma center.

If a lung has been penetrated, you may discover what is known as a sucking chest wound. We’ll cover sucking chest wounds specifically in another article in the future, but here’s a quick rundown: When a hole has been created in the chest wall and into the pleural cavity (the anatomical space that the lung lives in), air is able to enter around the lung and cause it to collapse. As the pressure in the pleural cavity increases, this can lead to shock by preventing the effective filling and pumping of the heart. Sucking chest wounds are more commonly discussed in regards to gunshot wounds, but they can happen as a result of an impalement as well. A sucking chest wound can be identified by the sound of air entering the chest cavity and by bubbling, frothy blood at the injury site.

Treating this injury when there is no impaled object is a much simpler task. The main idea is to seal the wound with an occlusive (air-tight) dressing. This could be as easy as saran wrap or the plastic wrapper from another dressing in your trauma kit. If possible, attempt to seal off the wound around the impalement with an air-tight dressing prior to stabilizing. If you don’t have anything available, don’t waste time on it. Focus on bleeding control and object stabilization.

Whether a chest impalement is a sucking wound or not, wrapping the chest circumferentially should be avoided. The extra manipulation needed to wrap around the chest can cause further injury and wrapping too tightly can inhibit effective expansion of the chest on inhalation. Apply your bulky dressing and secure it with tape. Some men have hairier chests than others, and an abundance of thick man-fur can prevent the tape from sticking. While we carry razors in the ambulance for just such occasions, it’s probably not something you keep in your first aid or trauma kit (though you might consider adding it). You might have to get creative and do something like an improvised duct tape wax job.

Any chest injury (or neck injury for that matter ) is likely to mean the patient will have trouble breathing effectively. This can cause the patient to panic and is frightening to witness when you don’t know what to do nor have any way of fixing it. Remember to stay calm and provide reassurance.

The abdomen houses a large number and variety of organs and the major vessels — abdominal aorta and vena cava — coming from and going to the heart. The liver and spleen can also cause severe internal hemorrhage if damaged. Stabilizing the abdomen can be difficult depending on the object and the physical size of the patient. Tape or gauze or other similar stretchable bandages can be used to secure a bulky dressing to the abdomen.

Moving a patient with a chest or abdominal impalement is a concern and should be avoided if possible until EMS arrives. Keeping the patient flat on their back is best to prevent further movement and damage. If you’re out in the middle of nowhere, you might need to work on your skills with building a field-expedient stretcher.

Extremities

While the extremities have fewer and smaller blood vessels and no internal organs, they still present a real danger of life-threatening blood loss. Continue the same idea of applying bulky dressing to stabilize the object and securing it with gauze wrap. The advantage of the extremities, though, is that if bleeding isn’t controlled by your bulky dressing and pressure, a tourniquet can be placed.

In addition to stabilizing the object itself, it can help to apply a splint to the affected limb. Former combat medic Bruce West has a great article on lower extremity splints (with some helpful tips for trauma assessment, to boot). Reducing movement can be done with an extremity by isolating and immobilizing the affected limb rather than keeping the patient lying still on their back.

Exceptions

There are, as always, exceptions to the rules; here are a couple that apply to the general prohibition against removing the impaled object:

If you have an object that has impaled the cheek, you can see both ends of the object, the only thing affected is the cheek, and the patient is awake and alert, you can generally remove the object safely (though just because you can, doesn’t mean you should). Be prepared to control any (probably limited) bleeding in this case. EMS is (depending on their protocols) able to remove an object if it is interfering with the patient’s airway or their ability to use an advanced airway if needed.

If the impaled object is in the chest and interfering with chest compressions during CPR, it’s okay to remove the object. Note: it’s essential to make sure compressions are actually needed due to a cardiac arrest. Don’t be that guy doing compressions on somebody that isn’t dead yet. Let’s say you’re at your local axe throwing chapter, and your buddy takes an axe dead center of his sternum and keels over. Ensure he’s actually dead, toss the axe aside, and get down on some chest compressions.

The idea here is that if you’re doing compressions, the patient is clinically already dead. Any damage done by removing the object isn’t going to cause further harm to an already dead person. We’ve now moved on from “best possible outcome” to literal life or death.

Conclusion

While this article only covers immediate, temporary care of an impaled object, there are a dozen other things that must be considered in a traumatic situation: performing a thorough physical assessment of the patient, treating for shock, treating other injuries, and more. Training is of paramount importance when placing your or another person’s life in your hands.

_____________________________________

Charles Patterson is a husband to a beautiful wife and father of five wonderful children. After serving as a linguist in the Marine Corps and earning a degree in Music Production after discharge, Charles found his true passion as a paramedic. When the work is done and the chores are finished, he enjoys cycling, mountain biking, shooting guns, frisbee golf with his family, and playing guitar.