With our archives now 3,500+ articles deep, we’ve decided to republish a classic piece each Sunday to help our newer readers discover some of the best, evergreen gems from the past. This article was originally published in August 2019.

Editor’s Note: This is a guest article by Marine Corps veteran and paramedic Charles Patterson.

Imagine this scenario: you’re in line at an airport ticket counter getting ready to leave for a well-earned vacation with your wife. The kids are safe and sound with your parents, you made sure the stove was off before you left the house, and you even remembered your toothbrush. Then the man in front of you — who’s been arguing with the ticket agent about the weight of his luggage — suddenly grips his chest, cries out in pain, drops his carry-on, and falls to his hands and knees. His wife screams and frantically starts shouting, “Bill?! Bill! What’s wrong?! Bill!” The man rolls over to a sitting position against the ticket counter and you notice his face has gone pale and he looks scared. While you’re watching, he stops responding to his wife and slumps over.

What just happened? Your wife looks at you with a Do something! expression and indeed you want to do something, but you don’t even know what happened, let alone what to do. You hear somebody yell, “Call 911!” and you fumble for your phone, unsure of what to even say if you do call.

Bill just suffered a heart attack. His years of overeating, infrequent physical activity, refusal to take his blood pressure medicine, and the on and off chest pain he’d been ignoring the last few months culminated in a singular episode that may have just killed him.

The characters and the settings change, and the causes and results vary, but a scene similar to this plays out in people’s hearts many times a day, every single day, all over the world.

Every year in America nearly 800,000 people have a heart attack — and the majority of them are men. Heart attacks most commonly occur in patients with some form of heart disease. Heart disease (a term encompassing several conditions) is one of the leading causes of death in the United States, with more than 600,000 deaths per year, and most of these are a result of heart attacks and strokes.

With statistics like these, it is very likely that you or someone you know has been or will be affected by a heart attack. A heart attack may result in sudden cardiac arrest, where the heart stops beating, but most heart attacks are survivable. The good news is that with a little education you can recognize the signs, symptoms, and risk factors of a heart attack, as well as what to do if you, or someone around you, has one.

The Physiology of a Heart Attack

While there are a few ways that a heart attack can occur, the majority happen as a result of a clot formation in the coronary arteries. Heart attack patients typically have some form of coronary artery disease, commonly atherosclerosis, which is the buildup of plaque along the walls of the coronary arteries. These plaque deposits can rupture or break off under high pressure. When they do rupture, the blood is exposed to the plaque’s necrotic core, which causes a clot formation. As this clot grows and blocks the vessel, blood flow to the rest of the heart is reduced and can eventually stop. As a result, oxygen cannot get to the rest of the heart and the tissue begins to die.

Tissue that is becoming starved for oxygen is called ischemic tissue. In the heart, this is called cardiac ischemia. If the tissue goes too long without oxygen, it becomes permanently damaged and is said to be infarcted. This permanent tissue death of the heart muscle is a myocardial infarction — which literally means “death of heart muscle.”

When part of the heart muscle becomes damaged or dies, the heart’s ability to pump blood is reduced. Imagine suffering a permanent injury to your arm that prevents you from doing as many bicep curls as you could before. How badly the heart muscle is damaged depends on a variety of factors, including where the clot formed in the coronary arteries and how long the patient goes without treatment.

While many heart attacks are not fatal, the damage that they cause has lasting effects that may directly lead to further heart problems or may increase the risk of future heart attacks and other conditions.

A heart attack may result in:

- Congestive heart failure (a progressive condition where the heart no longer pumps efficiently)

- Irregular, sometimes fatal, heart rhythms

- Increased risk of stroke

- More heart attacks

Heart attacks that are fatal cause enough damage to the heart that it stops beating. This is known as sudden cardiac arrest. The vast majority of people who go into sudden cardiac arrest — upwards of 90% — unfortunately do not survive. If caught quickly, though, a heart can sometimes be shocked back to a normal rhythm. The chance of this is very low, however, and with the small percentage who do survive, many of them are not able to return to a normal life.

Risk Factors for a Heart Attack

While it is certainly possible for anyone of any age to have a heart attack due to congenital heart defects, drug use, or other causes, there are certain factors that increase the risk of a heart attack. Most are caused by underlying heart disease; therefore, the risk factors for a heart attack are mostly the same as for heart disease.

Some of these factors we can control, either through lifestyle changes or through medicine prescribed by a physician. These include:

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- High cholesterol

- Poor diet

- Obesity

- Stress

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Smoking

- Illicit drug use

- Uncontrolled diabetes

With these factors, lowering your risk of having a heart attack can be as simple (I said simple, not easy!) as eating healthy and exercising regularly. Talk to your doctor about medications and lifestyle changes that can be used to reduce these risks. In the case of uncontrolled diabetes, remaining compliant with your insulin or medications, maintaining a healthy diet, and seeing your doctor at regular intervals can decrease the risk of commonly related conditions.

Some risk factors that can’t be controlled include:

- Sex: heart attacks are most common in men.

- Age: the older we get, the more at risk we are for developing coronary artery disease and thus having heart attacks. The risk of heart attacks in men increases after age 45 (55 for women), and the average age for a first-time heart attack is 66 (age 70 for women).

- Family history: people with a family history of heart disease and heart attacks are more likely to develop the same conditions. This can be genetic, but it can also be common environmental factors or learned behaviors such as alcoholism, poor diet, drug use, or higher stress levels.

- Race: certain ethnicities have shown higher prevalence and incidence of heart disease, its risk factors, or associated diseases than others, including African-Americans, Native Americans/Alaskan Natives.

Some medical conditions can also lead to increased risk of heart disease, including thyroid and adrenal gland disorders. It is important to talk to your doctor to learn more about your individual risk factors, underlying medical conditions, and what you can do to maintain a healthy lifestyle.

To read more about risk factors and steps you can take, visit this page from the American Heart Association.

What Does a Heart Attack Look/Feel Like?

While there are a variety of common signs and symptoms, the classic symptom of a heart attack is chest pain. Somewhere in the neighborhood of 70% of heart attack patients experience chest pain (you likely thought it would be 100%!). This pain is usually felt in the center or left side of the chest and may or may not radiate to the left arm, neck, jaw, or the back between the shoulder blades. Chest pain is also often described as pressure, tightness, heaviness, or “like someone is sitting on my chest.”

Other common symptoms include:

- Sudden and profuse sweating

- Cool, clammy skin

- Appearing pale

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

- Acid reflux

- Upper middle (“epigastric”) abdominal pain

- Nausea (with or without vomiting)

- Syncope (fainting or passing out)

- Lightheadedness or feeling weak or faint

- Feelings of anxiety, irritability, or restlessness

- An impending sense of doom

Though chest pain is the hallmark sign of a heart attack, many people will not experience pain at all. Women, diabetics, people with neuropathy, and the elderly are especially likely to experience what’s known as a “silent” heart attack that presents without chest pain.

The difficulty with a silent heart attack is that the symptoms you may feel could also be symptoms of other illnesses or may be so vague that you don’t feel the need to seek help. While you may explain your acid reflux and upper abdominal pain as “probably my dinner disagreeing with me,” never be afraid to seek help if something doesn’t feel right.

Men in particular tend to put things off or ignore health issues. We like to shrug it off, ignore it until it goes away, or make excuses and denials for our symptoms. Don’t wait, and don’t be stubborn. It’s important to act fast; you need to get to a hospital in about 60 minutes or less to minimize accruing permanent, irreversible damage to your heart. As we like to say, “time is life” or “time is muscle.”

Is It a Heart Attack? Or Something Else?

It’s worth noting that some of the symptoms listed above may also be signs of other medical conditions. In the right combinations, these symptoms can suggest shock from other causes, pulmonary embolisms (a clot in the blood vessels of your lungs), aortic aneurysms (the ballooning of part of the aorta in either the chest cavity or abdomen), irregular heart rhythms, certain thyroid conditions, and many more. If you’re not sure if what you’re experiencing is a heart attack, get help. Heart attack or not, these are all serious conditions that may be fatal without medical care.

One condition in particular that can result in symptoms that feel like a heart attack is a coronary artery that is partially blocked due to plaque buildup. Due to this partial blockage, the heart is not able to get enough oxygen and you may feel chest pain or other symptoms. This is called angina. Angina often occurs with physical exertion or stress — when the heart’s demand for oxygen increases — but it may also occur while at rest. The pain or symptoms may or may not go away with time and rest. Angina is not a heart attack, but it is a sign of underlying heart disease and a warning sign of a heart attack.

In the same way that a broken bone cannot be diagnosed without an x-ray, the difference between angina and a heart attack cannot be determined without evaluation and testing by a doctor. If you’re having chest pain or any of the other above symptoms, never assume it’s “just” angina. Again, err on the side of safety and get help.

What to Do in the Event of a Heart Attack

If you believe you or someone you know is having a heart attack, it is important to act quickly while remaining calm. A knowledgeable bystander who recognizes when someone may be having a heart attack is the first and most important step in what the American Heart Association refers to as the “Chain of Survival.” Without the bystander or the patient recognizing the symptoms and deciding to act, the other links in the chain of survival cannot be put into action.

- Before you do anything else, CALL 911 (or your local emergency number). Be sure to provide the dispatcher with your location, describing where the patient is as best as you can to guide EMS when they arrive. If you’re in a large building such as a store, warehouse, or office building, consider sending another person (if available) as a guide to wait for EMS. The dispatcher will ask you for other information about the patient and their condition. Stay with the patient and remain calm while providing this information and stay on the line until EMS arrives.

- Place the patient in a position of comfort. While it is widely understood that the best position for someone in shock or with shock-like symptoms is lying on their back with their feet elevated, a person having a heart attack may be having a hard time breathing and could have fluid in their lungs (a condition known as pulmonary edema) which makes breathing difficult. Sitting upright may relieve this to some degree. Place the patient in whichever position is most comfortable for them.

- Give aspirin, if available. If the patient is awake and conscious enough to follow directions and swallow safely, give them aspirin. The typical recommendation is 162-325 mg (2-4 baby aspirin, or 1 full strength), chewed and swallowed. Chewing before swallowing increases the rate of absorption and will allow the drug to act faster. Aspirin is often referred to as a blood thinner, but it is technically an anti-platelet medication. Aspirin causes platelets in the blood to become less adherent to each other and thus prevents clotting. Make sure the patient isn’t allergic to aspirin before giving it! (For situations like this, it can be a good idea to keep some aspirin in your own first aid kit!)

These initial steps can have a significant impact on the survivability of a heart attack. If you take away nothing else, the most important step is to call 911 immediately to activate emergency services.

If the patient becomes unresponsive, they may have gone into cardiac arrest. Don’t assume they have and try to start CPR; they may have just fainted or become unconscious. First:

- Check for responsiveness by shaking the patient at the shoulder and addressing them: “Hey buddy, are you okay? Can you hear me?” If you know their name, address them by name.

- If they remain unresponsive, lay the patient flat on the floor and feel for a carotid pulse (that’s the one at the neck).

- “Look, listen, and feel” for evidence of breathing. Place your face above the patient’s mouth and look towards the chest. Look for the rise and fall of the chest, listen for breath sounds from the patient’s nose and mouth, and feel for their breath on your face while you feel for their pulse.

- If you can feel a pulse and they appear to be breathing normally, do not initiate CPR; just continue to monitor their heart rate and breathing until EMS arrives.

If you cannot feel a pulse and the patient has stopped breathing, they have gone into cardiac arrest. The best chance for this patient now is to start CPR and give a shock from an Automated External Defibrillator (AED). The emergency dispatcher may guide you through steps to begin what is known as “hands-only” CPR and using an AED if one is available. An AED provides easy-to-follow audio or video instructions to safely and effectively deliver a shock. If a patient goes into cardiac arrest, starting CPR and giving a shock with an AED as soon as possible can mean the difference between life and death. We’ll explore this more next.

CPR and AEDs

Performing CPR

If you’ve never experienced it firsthand, CPR in real life is very different than what is sometimes portrayed in movies and television. In movies we often see someone giving a few soft pats or gentle presses on the patient’s chest (or in the really bad examples, on their stomach) or a single grandiose thump of the chest and the patient returning to full consciousness suddenly and dramatically with a huge gasp and a “Whoa, what happened?!” CPR in real life does not work this way and does not return the patient miraculously to life.

CPR is performed to prolong life until advanced care is received. The compressions performed in CPR manually force the heart to pump blood to the body, providing oxygen to the brain and other vital organs, until the heart can be jumpstarted with an electric shock from an AED or by EMS or hospital staff with advanced heart monitors and drugs such as adrenaline (epinephrine). Even if these devices and drugs return the heart to a normal rhythm, the patient may not return to consciousness immediately or at all. Unfortunately, the large majority of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests are ultimately fatal. By giving high-quality CPR and early shock from an AED, however, we give a cardiac arrest patient the best chance of life.

If you are with someone who has gone into cardiac arrest, you may be directed by the emergency dispatcher to perform CPR before the EMTs or paramedics arrive. For bystanders, the common advice now is to perform “hands-only CPR”; unlike traditional CPR, hands-only CPR does not involve “mouth-to-mouth” or other means of breathing for the patient, but chest compressions only.

I recommend everyone seek CPR (and AED) training. Having hands-on training to help you understand the mechanics of CPR and feeling the appropriate rate and depth of compressions is extremely beneficial and cannot be matched by simply watching a video or reading instructions online. Being able to go through the steps of CPR on a dummy will help you build confidence and remain calm in the event of an emergency.

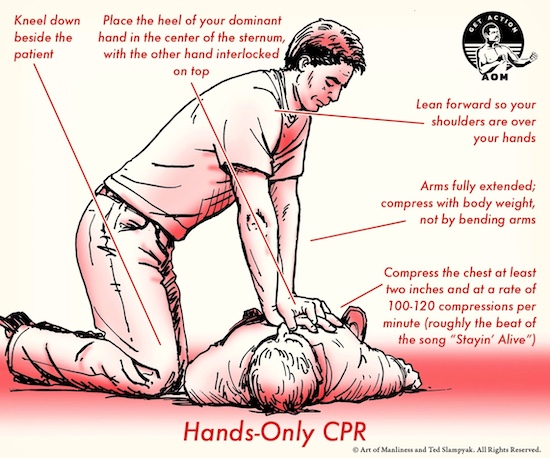

That being said, for informative purposes only, hands-only CPR for an adult is basically performed as follows:

- Kneel down at the side of the patient.

- Place the heel of your palm (of your dominant hand) in the center of the patient’s sternum. Interlock the other hand on top of the first.

- With your arms fully extended and leaning forward so your shoulders are above your hands, begin compressing the chest with your body weight. Do not compress with your arm strength by bending your arms.

- Compress the chest to a depth of at least two inches and at a rate of 100-120 compressions per minute. I was taught to sing the refrain from “Stayin’ Alive” by the Bee Gees while doing CPR to get an idea of the appropriate rate (although, in the middle of an actual CPR event, I’ve never had the Bee Gees pop into my head or felt much like singing).

Many attempts at CPR by untrained persons ultimately fail because the depth and rate of compressions are not sufficient. People worry about pushing the chest too hard because they don’t want to hurt the patient. At the risk of sounding harsh, if you’re performing CPR the patient is already basically dead; you are not going to hurt them by compressing fully.

Once you begin hands-only CPR, don’t stop! Keep compressing the chest until EMS arrives. Consider trading off compressions every couple of minutes with another bystander so you can continue to provide effective compressions; proper CPR will wear you out, and as you grow tired your compressions can become slower and shallower. Stick with it! If you do have to stop, limit breaks to 10 seconds or less.

Administering an AED

Remember: CPR is performed to prolong life until a shock from an AED or by EMS is given. As soon as an AED is available, use it.

Many public buildings and workplaces have AEDs available in the event of an emergency. Every state has some law or regulation regarding AEDs, and some states require them in certain locations, such as health and fitness centers. You may have seen signs at public locations with “AED HERE” or similar to alert the public to the location of these devices. They may also be accompanied by kits that include trauma shears to remove clothing for the placement of AED pads, protective barrier devices to give mouth-to-mouth respirations during CPR, and sometimes even a razor to shave the chest (if there is excessive hair, which prevents the pads from sticking properly). Check with your workplace if an AED is available in an emergency and keep an eye out for them while you’re running errands.

Despite the many manufacturers and models of AEDs, using one is almost universally the same:

- First, turn the AED on. The device will begin providing instructions with audible or video-guided cues. The specific instructions do vary slightly between models, so follow the prompts.

- Apply the pads to the patient’s bare chest. Yes, this means bare for women, too. If the patient is sweaty or wet, dry the chest off before applying the pads. The pads are typically kept in a package that has an image showing where each pad goes. One pad will be placed on the chest to the right (the patient’s right!) of the sternum and below the collar bone. The second will be placed under the left pec/breast. If you have another bystander with you, apply the pads while they’re performing CPR. Don’t stop until the device instructs you to.

- The AED will direct you to stop CPR if it is being performed and to not touch the patient while it analyzes the electrical rhythm of the patient’s heart. If a shockable rhythm is detected, the AED will say something along the lines of “shock advised” and will begin charging.

- Repeating again to stay clear of the patient (humans are great conductors of electricity) the AED will instruct you to deliver a shock by pressing a button on the device.

- Making absolutely certain that no one is touching the patient, deliver the shock. Be aware of things such as metal around the patient or puddles of water that may conduct the electricity to you even if you’re not in contact with the patient directly.

- Once you’ve delivered the shock, the AED will instruct you to continue CPR. After two minutes of CPR, the AED will repeat the steps of analysis, charging, and delivering a shock with the continued audible and/or visual instructions. This will continue in cycles of CPR and shocks until EMS arrives.

A quick search on YouTube turns up several videos from the American Heart Association and American Red Cross that demonstrate these steps for reference, but just as with getting hands-on training in doing CPR, nothing replaces real world practice in how to use an AED. You may never be put in a situation to use these skills, but if you are, you’ll be glad to have the training.

The American Heart Association has many training options for everyone from professional responders to everyday people, including options for certification if required for a job. Some of these training options include full First Aid, CPR, and AED training, but you can also find training just for the hands-only CPR we’ve discussed. The American Red Cross offers similar training options. Both of these organizations offer online, in-person, or combination courses and additional training materials to suit your needs.

What to Expect From EMS and at the Hospital

So far, we’ve discussed how heart attacks are caused, how you can reduce your risk of having one, and what to look for and what to do if you witness someone having a heart attack. What a lot of folks aren’t familiar with is what to expect once you’re in the ambulance or at the hospital. During these high-stress and emotionally charged situations it is easy for things to seem quite chaotic. It may help you to have a better understanding of what is happening.

Depending on where you live and the resources available, you may have 2-6 EMS responders arrive. Some areas have limited EMS resources and you may only have two EMTs arrive. Other areas have fire departments that respond with an ambulance and a fire engine carrying up to 6 paramedics. Regardless, every member of these teams has a specific role to play during a heart attack. These roles and procedures performed may vary slightly based on responder certification and whether the patient is still conscious or not. The steps I mention are very similar in both a paramedic-staffed ambulance and an emergency department. Depending on the individual situation, most of these steps are performed concurrently.

While the following procedures are happening, one of the responders will also be talking to the patient, asking about their symptoms, medical history, prescription medications, and other information. If the patient is unconscious, they’ll attempt to gain the same information from a family member or bystander.

Initially, vital signs are gathered including blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen percentage, and a 12-lead EKG is performed. An EKG involves placing a bunch of stickers (electrodes) connected to wires on the patient’s chest, arms, and legs. These wires are connected to an advanced heart monitor that can read the electrical signal from the heart and give 12 different views (leads) of that signal. The 12-lead can show signs of a heart attack and which part of the heart is being affected. (A 12-lead can also detect irregular heart rhythms and a wide assortment of conditions other than a heart attack, so they are widely used in EMS and hospital settings for more than just suspicion of a heart attack.)

If the patient is in cardiac arrest when EMS arrives, they will take over CPR and connect the patient to their heart monitor, which has an advanced version of an AED. They will continue the cycle of CPR and delivering shocks on the way to the hospital while adding the other steps mentioned below.

If the patient is still conscious, they may be given extra oxygen either through a nasal cannula (the small tube you see under the nose that wraps around the ears) or a non-rebreather (a mask that covers the nose and mouth with a bag attached to the bottom) depending on how much extra oxygen the patient needs.

The patient may be given aspirin if it hasn’t already been given, as well as another drug called nitroglycerin. Often referred to simply as “nitro,” nitroglycerin helps to dilate blood vessels, and can open up the affected coronary arteries and allow more blood flow past the blockage. Nitroglycerin may or may not be used depending on the patient’s vital signs. Patients can be prescribed nitro for certain heart conditions and although the patient may take this as directed, avoid giving it to them yourself. Nitro can be helpful, but in the right situations it can actually make matters worse. EMS and hospital staff are trained to recognize these situations.

They will start at least one, but often two IVs (intravenous access). Placing an IV allows responders to give medication, such as morphine, directly into the blood. Morphine can quickly relieve pain; relieving pain can reduce the patient’s stress and the workload of the heart. Fluids may also be given to increase blood pressure if it is too low. If the patient is in cardiac arrest, other drugs such as adrenaline will be given through the IV in an effort to chemically kickstart the heart (Motley Crüe, anyone?).

Some EMS agencies and hospitals will instead start what’s called an “IO” if the patient is in cardiac arrest. An IO, or intraosseous access, is a needle placed into a bone, allowing medications or fluids to enter the blood through the bone marrow. This works nearly as fast as an IV (the difference is mostly imperceptible) and can be faster and easier to start when the heart is not pumping blood. An IO is started with a small handheld drill which can seem rather vicious to family members watching, but this is a fast process and it helps to remember that the unconscious patient cannot feel it.

Initially, artificial breathing for the patient will be done by a bag about the shape and size of a football that is connected to a face mask and squeezed to deliver air. This method of breathing is not perfect, though, and some of the air inevitably leaks outside the mask or makes its way to the stomach instead of the lungs. Different EMS agencies have different rules, but if allowed, paramedics will perform a procedure called endotracheal intubation.

Endotracheal intubation means that a small tube will be placed directly into the trachea, allowing all the air that is delivered from the bag to go straight to the lungs. It can be a frightening thing for family members or bystanders to witness, but it is more effective for delivering much-needed oxygen. It is also ultimately safer for the patient, as it keeps the airway open and prevents vomit, blood (if present), or other secretions from getting into the airway. It effectively seals off the lungs from anything other than oxygen-rich air.

Once the patient is at the hospital and stabilized, blood tests will be performed to look for certain enzymes and hormones released by the heart during a heart attack. The patient will be sent to the cardiac catheterization lab (or “cath lab” for short) where a doctor, guided by advanced imaging, can perform a variety of minimally invasive procedures to increase blood flow to the coronary arteries and place stents or balloons to keep these vessels open. Afterward they’ll be transferred to the ICU. Not all patients require a visit to the cath lab; some may need more drastic procedures and some may just be taken straight to the ICU. There are too many variables and too many resulting possibilities to list here.

You must also prepare yourself for the possibility that, despite all efforts, the patient may not leave the emergency room. While not all heart attacks are fatal, many are, and ultimately, most people who go into cardiac arrest cannot be resuscitated and will die.

This is not an eventuality that any of us want to face. But armed with a little knowledge and advice from your doctor, you can take steps to reduce your own risk of heart disease and heart attacks, and encourage those you love to do the same. Don’t put it off. Make an appointment with your doctor and sign up for a CPR class. By knowing what to look for, keeping your cool, and taking a few simple actions, you can make a difference and maybe even save the life of someone you love.

_____________________________________

Charles Patterson is a husband to a beautiful wife and father of five wonderful children. After serving as a linguist in the Marine Corps and earning a degree in Music Production after discharge, Charles found his true passion as a paramedic. When the work is done and the chores are finished, he enjoys cycling, mountain biking, shooting guns, frisbee golf with his family, and playing guitar.