Before Arnold Schwarzenegger, even before Charles Atlas, there was Eugen Sandow. Rising from obscurity in Prussia, Sandow became an international celebrity during the Golden Age of the Strongman in the late 19th century for his amazing feats of strength and his well-sculpted physique. While Sandow wowed crowds in the United Kingdom and United States, he also preached a new gospel of physical fitness and well-being.

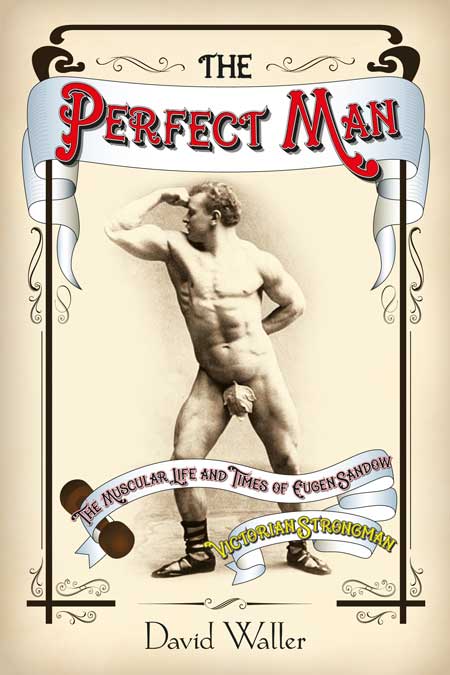

Our podcast guest today has recently published a biography of Sandow and his times. His name is David Waller, and his book is The Perfect Man: The Muscular Life and Times of Eugen Sandow, Victorian Strongman.

For more information about the book, visit Victorian Strongman.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. Before Arnold Schwarzenegger and even before Charles Atlas, there was Eugen Sandow. Rising from obscurity in Prussia, Sandow became an international celebrity during the Golden Age of the Strongman in the late 19th century for his amazing feats of strength and his well-sculpted physique. While Sandow wowed crowds in the United Kingdom and United States, he also preached a new gospel of physical fitness and well-being.

Our guest today has recently published a biography of Sandow and his times. His name is David Waller, and his book is The Perfect Man: The Muscular Life and Times of Eugen Sandow, Victorian Strongman. Mr. Waller has worked as a journalist for the Financial Times and has written and published two books on business. He lives in Southwest London with his wife and three children. Well David, welcome to the show, its great having you.

David Waller: It’s great to be here Brett.

Brett McKay: So you’ve written this book about the strongman Eugen Sandow. For those who out there, who’re listening, who never heard of Sandow, can you kind of give a short biography of who was he and what did he do?

David Waller: Of course. It will be a great pleasure. 100 hundred years ago Eugen Sandow would have been one of the most famous people on the planet. He was famous in North America, he was famous in Great Britain, he was famous in Europe, he was famous the length and breadth of the British Empire. And he was famous for having the most extraordinary male body, obviously male body. He was known in his day as a perfect man and is celebrated for the perfection of his body, but also for being one of the strongest people on the planet as well. He never actually said that he was the strongest man in the world, but other people made that claim for him, so that’s really who he was in terms of celebrity at his hey-day.

He was born in 1867 in East Prussia, in a place that is now part of Russia, Königsberg, it no longer exists. It’s actually called Kaliningrad now at that was in 1867. And he came to a prominence in 1889 when he jumped on to a musical stage in London and into a challenge and won this challenge and thereafter became almost overnight a celebrity on the musical stage. In 1893 he came to North America, spent a number of years over in your part of the world and became very celebrated on the vaudeville circuit. And he went back to London in 1897, a very rich man; he had accumulated $250,000 of earnings by that time. And he got – he set up a fitness establishment and a mail-order fitness in which he sold the secrets of bodily perfection by mail order. And he had tens if not hundreds of thousands of adherents all around the world.

And then he went on to build up an even more ambiguous ambitious business empire. For example, manufacturing coffee and cocoa products and I will say that it all went badly wrong at the time of the First World War and his business failed and after the First World War he went into obscurity and when he died in 1925, he was actually buried in an unmarked grave in Putney Vale Cemetery in Southwest London.

Brett McKay: Wow! So he was really the proto Arnold Schwarzenegger, the Jack Lalanne. I mean he was one of the first people who kind of got involved in the physical fitness movement then.

David Waller: Yeah. He invented they didn’t call it physical fitness in those days, they call it physical culture and he really was the pioneer of that. And Schwarzenegger exclusively credits some of his own training and some of his own motivation to Sandow, Sandow exercise regime and Schwarzenegger based his own regime in his early days. He is a strong man, a body builder on the Sandow’s recommendations.

And as you will know that in the Mr. Atlas body building competition, you get a Sandow statue at – a little statue of Sandow not wearing so many clothes, but he had this kind of body that is still to be celebrated in those circles. And Charles Atlas also owed a debt to Sandow. So he really was the very first person to be anything more than if you like a circus strongman.

Brett McKay: So I mean what – that’s one of the impressions I got when I was reading this book was that what Sandow was doing was something new, it was bizarre. I mean the whole idea of shaping your body and being obsessed about your muscles and exercising and nutrition, that – it was sort of a novelty during the Victorian times. What was the state of physical culture as you said around the turn of the century and how did Sandow changed the conversation about and or get people excited about physical fitness?

David Waller: He started off like a circus strongman. He wasn’t actually on the circus stage, but he had performed in musical which is a popular culture at its most lively. In London there were 400 or 500 of these musicals and the American called these musicals vaudeville, and there were many strongmen. And what you had to do to keep your audience entertained by doing feats of strength and just being rather more ingenuous in lifting up people sitting on a piano for example or elephants or canons. Sandow at one point balanced the canons on his nose. I mean in his early days he was kind of like a showman.

What he did quite remarkably would take the celebrity which he won from the stage to propagate this philosophy of physical culture. And this is very scientific. He had what appears to be a very detailed knowledge of anatomy. He claimed he studied at University of Germany. We don’t know if that’s actually true, but he knew the name of all the muscles in the body and he had a philosophy which was a basically – if you exercise a little and a lot in a very controlled fashion using a dumbbell, we’ll come back to that, but he recommended to use his own patented dumbbell, but with a relatively small investment of time and effort you could actually change the way you looked, changed your shape and in fact transform your whole personality.

And I wonder it was a very modern concept by exercising in the privacy of your own room, this wasn’t coming to the gym particularly, but some you could do at home and you could actually look like him. But what he did was he turned his own body, not just his name, but his own body into a kind of global brand. And his message was look if you follow my resume, you too can look like me.

Brett McKay: And one of the things I remember reading I thought was really interesting was how the British military where – they were concerned the fitness level of British men and at this point they were trying to manage a vast empire. And they were concerned that British men weren’t up to the task of doing that, because they’re just so out of shape. I mean the people does not exercise back then, I mean was that – I mean they do not really think about that? They just sit – what was their idea of physical fitness before Sandow came in and actually showed them his scientific approach to physical culture?

David Waller: Well people clearly play sports and the kind of sport you pursued did depend on your social class, so upper class men will go hunting for example or those things or working class men would play football and…play rugby in those days. But what people didn’t do was train in a systematic way to achieve physical fitness. And Sandow made this distinction between what creational exercise, so in other words the exercise you get when running around a football pitch and this kind of disciplined scientific exercise which got a very clear objective of increasing your physical fitness. So that was his philosophy.

Now, how did that touch on the moods of the British nation at this time? Of course in late 1890s, Britain had the biggest empire that the world has ever seen. But why where they worried? They were worried because personally there were challenges to that power wherever they’ve gone, but in particular in South Africa and this is the time of the Second World War. And this was a challenge to British power from a range of farmers outwards tough, wiry Boer farmers who were Dutch origins and they came very close to defeating the British Empire and humiliating the British Empire in a whole series of the battle in 1900s, early 1900s.

And to your point when Britain looked for volunteers among its own population, there were many, many 10s of 1000s of man who wanted to sign up and go and fight. But their physical conditions turned out to be quite poorly and it’s especially true of kind of working classmen from the cities like Manchester, the north of England for example and also London of course. These people had a very poor diet. They didn’t really do any sport or exercises at all. They were much shorter than people who were of higher social economic status. So up to half of the volunteers from Manchester for example were turned down on the basis that they were not physically fit. So Sandow came along and said I can help this nation. If you follow my exercises I can turn these weaklings into paragons of strength.

So it’s something – somewhat ironic, because of course Sandow himself is not British. He wasn’t even a British citizen, but he came from Germany, but he was helping Britain to become more effective as a military mission.

Brett McKay: So earlier you talked about how Sandow got his start as a stage show strongman and I find this whole aspect of the time period, this is very fascinating, the whole – this whole aspect of popular culture during Victorian times. There was this obsession with strongman and it’s one of those I guess iconic images of the men in a leotard with a handlebar mustache lifting up a dumbbell in excess of 1000 pounds. How much of that stage – those feats of strength, how much of that was actually Sandow, display of his strength and how much of it was a little bit of wink-wink showmanship going on there?

David Waller: Well that’s a very good question. There was a lot of showmanship. But it is interesting that how Eugen who was no stranger to showmanship himself actually investigated the whole question of stage strongman. And he came to conclusion actually that Sandow was not a fraud. There were other people who were often caught out, even being fraudulent. So they will have dumbbells that were hollow and they were pretending that they were very heavy. But they have machines that it would look as though they were lifting up a horse, but actually they were using mechanical aid to help them with that.

But Sandow, he was intelligent, he had served sometime in a circus, he knew all about putting together an act which looks exciting and looks convincing and deployed tricks as well as just outlaws strength. So for example, one of his party pieces was to lift up a man who was sitting playing a piano. He lifted up both the man and the piano and he carted them upstage apparently with just using one arm, one hand or one arm. And there was a trick in it, because what he did was he put his hand behind the piano and there was a handle specially built where he could kind of slit his forearm in there and lift it up. Now it was still an incredible piece of strength. But it wasn’t quite of the naked show of thought that the audience might have seen and there were other examples.

I mean he was very good at supporting very heavy weights. So what he do, he lie on his back and put his chest and torso upward and they would put a plank or platform on top of him and on top of this they would then load up people, all the equipment on the stage, sometimes actual real horses and cannons when he was pretending to be doing a military scene. And they load up more than a ton weight would go on his abdomen stomach. And he could hold on to that, he could have lift it, but he could certainly support it.

And with another example, Edison, Thomas Edison filmed Sandow in an early visit to the U.S.; I think it’s about 1896. And Sandow, he was doing full somersault, sort of standing start holding two – I think a 56-pound dumbbells one in each hand. He is doing somersault with that and there was nothing fake about that. He would be very strong, he was very gifted and he was very elegant.

Brett McKay: What you think just your research in the book and the times, why where these strongman shows so popular? I mean why does someone like Sandow become an international celebrity?

David Waller: Well, I think there were lot of stage strongman, most of – and I thought nearly all of them never did anything more than this kind of show on the musical or vertical stage. Sandow went a lot further than that and I think he was one of the very first celebrities to feel like leverage the power of new media, the new technology that was available in those days. I mean it’s kind of quite a modern story and he became famous in Britain and rather like a kind of pop group today he realized that he have to go to America to really achieve global growth.

So he went there and because of the power of the photography and because of the telegraph and because of the increasing proliferation of new media, there were 1000’s of new magazines and newspapers in the 1890s patron to the very population love of news and story. Sandow was able to use what we call modern public relations technique to make his own name very popular, very well known. And that’s how he built up a brand. So he saw the opportunity. Where other people where content to earn a living on stage, he saw – he decided to go a lot further than that and build a business on the back of his stage name.

And in the interviews that he did towards the end of the 1890s and the early years of last century he said I don’t really see myself as a showman anymore. I have a much more serious mission and this is the education of the population into the philosophy and practical and physical culture. But I do my shows in order to keep myself and my – he didn’t mean to brand, but my name and my methodology in the forefront of people’s mind. So it was a bit like a kind of a rock star today perhaps or a film star who saw opportunities to be more than just appear on stage and make musical or act.

Brett McKay: Throughout your book you have pictures of Sandow just doing various poses, displaying off his amazing physic. But he is like pretty much naked, like the only thing he has on a lot of these pictures is like – is a leaf that’s covering his bits and pieces. And a lot of these – what I thought was fascinating, a lot of these images that there were photos that where taken of him where published in magazines. But the irony is that this was done kind of with the height of Victorian times with all the modesty and decorum that came with that. How was it that Sandow was able to pose half naked or pretty much naked and not receive a lot of scorn for that?

David Waller: Well it’s an extremely good question and I think what exposes more of just his near naked, if you will, is some of the double standards of the Victorian era. I mean in 1890s for example, for the first time ever on the British stage did the public get to see a naked ankle, a woman’s ankle and that caused a great scandal. So how come when it was scandalous to see a lady’s ankle on stage, but he get away with being near naked. I think there are number of observations.

Firstly he always clogged himself in the language of classical art and sculpture and he said look at me, because I turn my body into the little embodiment of classical sculpture. And at the time there was enormous reverence for everything to do with ancient learn in Greece. And the fact that he could pose as he did in the shape of the Dying Gladiator or Discobolus, these great classical statues gave the whole thing a kind of aura of almost academic respectability. I mean that’s one observation.

The other point was he always made sure to associate himself with doctors and soldiers and other respectable people who gave the fact that he was taking his clothes off just kind of venire of respectability. It was part of – it was almost like a public health project.

And then the other point was things were little lazier in your part of the world than they were in Great Britain. He only really started taking all his clothes off more or less when he went to America and he met Florenz Ziegfeld. Ziegfeld of course is well known for Ziegfeld Follies, but at the time of the Chicago World Exposition in – or the Colombia World Exposition rather in 1893, Ziegfeld’s first triumph in his career was with Sandow and Sandow was encouraged to take even more clothes off and then he was quite clearly sexy. It was designed to appeal particularly to the female audience. And in Chicago and Washington and New York and other big American cities, he would hold these kind of special sessions for society ladies who come backstage after the main show or would be allowed – they have to pay a little bit extra piece of it, they will be allowed to kind of plug his muscles and kind stroke the muscles and so forth.

And again because of these society ladies like Mrs. Pullman from Chicago and various Senators wives from Washington, because they went along the whole thing became acceptable. But I think it was very clever marketing in a way to make the whole thing risque without attracting real condemnation and that’s one of other observation.

Brett McKay: Go ahead.

David Waller: One observation. In 1901 the British Museum, the National History Museum in Britain decided to make a plaster cast of his body as a perfect example of the Caucasian man, the Anglo-Saxon man. And this plaster cast which by the way you can still see if you make special application, it’s hidden away in the fellow of the museum, but this was designed to show off things kind of this perfect body. And this was a scientific purpose, backing of various – very distinguish scientists. But after that six weeks of his naked statue being on display by the museum, the more conservative elements in British society caused it to be removed. There was a little bit of a scandal and it was taken down, so it wasn’t quite – he only get away with it, but he nearly have got away with it.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I thought that was some of the most interesting part in the book where you described these private showings with these society women and just of course they’re very tended to do it and then they would start off with a – their glove on their hand and touch his muscles and then they would have the glove off and they would be swooning and fainting and there would be smelling and all, I mean it was just – I thought it was really funny to kind of have…

David Waller: Yeah, it’s incredible that he could get away with it. I mean I can leave a little quote; this is from an American newspaper. “Wherever he went mobs paid dollars to see and after the mobs had looked their fill there were private séances to which nice people went; first in secret, then in brazen bravado”. Always ladies were present and always that private amazement was recorded in the dispatches. But though they are amazed, they carried and clearly fearly for a time they managed to… of the time and test the great muscle with a delicately gloved forefinger.

Brett McKay: Yeah. It’s amazing how times have changed. And I guess Sandow was part of – and in some sense he kind of began the liberalization of sexuality in the west.

David Waller: I think that’s right. I mean he himself steared clear of getting caught out in sexual liaisons, but William Russell seems to made an advance to him which he turned down. He was very controlled, very scrupulous. I think he used – he got a reputation for being a philander that would give him harm with the general public. So he was very hard to preserve his respectability and of course he got married in late 1890s to Blanche and after that really he let what appeared to be quite a respectable married life for a considerable period of time.

Brett McKay: What you’ve said so far and especially in your biography at the very beginning and talked about how he was an international celebrity. He was known across the world, in United Kingdom, the United States, he was just international celebrity of brand in and of himself. But we – most people don’t – haven’t really heard about Sandow and in fact he was buried in an unmarked grave. Why is it that we don’t hear that much about Sandow today?

David Waller: Well by the way the unmarked grave is about a mile away from where I’m sitting. I live in Wimbledon, I’m sitting – I’m talking to you from Wimbledon, very close to the tennis and just across what was in common is the Putney Vale Cemetery and that’s where he was buried. And a couple of years ago actually some supporters, some fans of him did cause a monument to be erupted to remember his name. But for a whole life century he was un-memorialized. And I think it clearly does away the question. I think the short – one question is what does he do to upset his wife, his widow Blanche and his two daughters and we just don’t know, but clearly they wanted nothing to be with his reputation.

And within he was dead one day – two days later he was buried and then within a month they sold everything in the family house and very soon afterwards Mrs. Sandow nearly got out of London and no one ever heard from her again. So I mean there were also stories about what he might have done to upset her. I mean other widows of course would cause a enormous amount of trouble to celebrate the memory of their loved one, she did exactly the opposite, so that was one factor that she just wasn’t around promoting Sandow’s name.

But I think the biggest question is what happened to these icons, the popular culture overtime. And I think the fact is that no matter how celebrated you were and perhaps no matter how celebrated you are and you could be basically going to be forgotten, it’s a lot of sad, but it’s something very human. And people especially for the bodybuilders like Charles Atlas and ultimately Schwarzenegger don’t knew all about him and so – and professional bodybuilders of this day will know all about him. But his reputation with the general public faded away. And I have to say there are references too in a plenty in the literature at the time. So from James Joyce’s Ulysses and to those novels by E.M. Forster, for example, wherever we turn he has written about that, but it will show how popular he was at the time. But I think by the time he was over 50, he died when he was 57, quite young. By that time his tremendous physic was fading, he became mortal and I think people were less interested to knowing about someone who really didn’t have the secret of eternal life after all.

Brett McKay: So this is a blog and a podcast about masculinity and manliness. What legacy did Sandow have on masculinity and manliness particularly in the west? What is it – how we’ve changed our idea of manliness because of him?

David Waller: Well I think one point; he emerged at a crucial time in the history of masculinity. It was almost exactly the point that the American West disappeared. It was also the time when Western Europe was in the midst of a profound period of industrialization. And the role of a man in those days, had changed from being someone who have to sight following on the frontier, defending his family from threats, building a log cabin, killing, killing what to eat there, and man would have to become tamed and become civilized and capable of living in society, often in cities with lots of other people around. And essentially if you’re a lot less vigorous that’s left behind them sort of existence.

And Sandow’s proposition was look, if you follow my exercise program you too can be a real man. You can be a real man within the constraints of society as it became more confining and more industrialized. And he had a particular pitch for the working man, the man who had to go to office, he had to commute, he didn’t have much time or lived in the suburbs and didn’t have much space work for those. And the pitch was look, if you do these exercises, just 19 of them everyday for 20 to 25 minutes, you’re going to transform your physic, you’re going to become a little bit more perfect, a little bit more lightening. So with empowering and it was empowering in a way that appealed to evolving the modern man.

I think there is one other consideration, it was also about posing, it was about showing off, it was about looking at the mirror, one of the things you encourage people to do to look in the mirror when they’re exercising, it helps increase concentration he said. But it was also about taking pride in looking good and having the right kind of shape. So I think that’s quite modern. So I see as like a patron saint of modern exercise today, not just gym exercise but people who go for jog, unconsciously have an awful lot to Sandow’s desire to put the whole things of exercise on to a kind of scientific putting.

Brett McKay: Great. Well David this has been a fascinating conversation. Thank you for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

David Waller: Brett, it’s been fantastic talking to you.

Brett McKay: Our guest today was David Waller. David is the author of the book, The Perfect Man: The Muscular Life and Times of Eugen Sandow, Victorian Strongman. You can find more information about David’s work at victorianstrongman.com and you could pick up a copy of his book, The Perfect Man at amazon.com. Well that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast, for more manly tips and advice make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. And until next time stay manly.