If you’re an endurance athlete, you’ve probably experienced “the Wall” at some point or another. It’s that moment in a race where you’re pushing yourself really hard and your body just tells you “Basta! Enough!” So you back off and slow down to a trot or even start walking.

Or if you lift weights you’ve probably had those days when a weight felt super easy, but another day when the same weight felt super heavy.

It’d be easy to think that this is your body telling you that you’ve had enough — that your muscles are fatigued and you can’t possibly go on.

But what if it’s all in your mind?

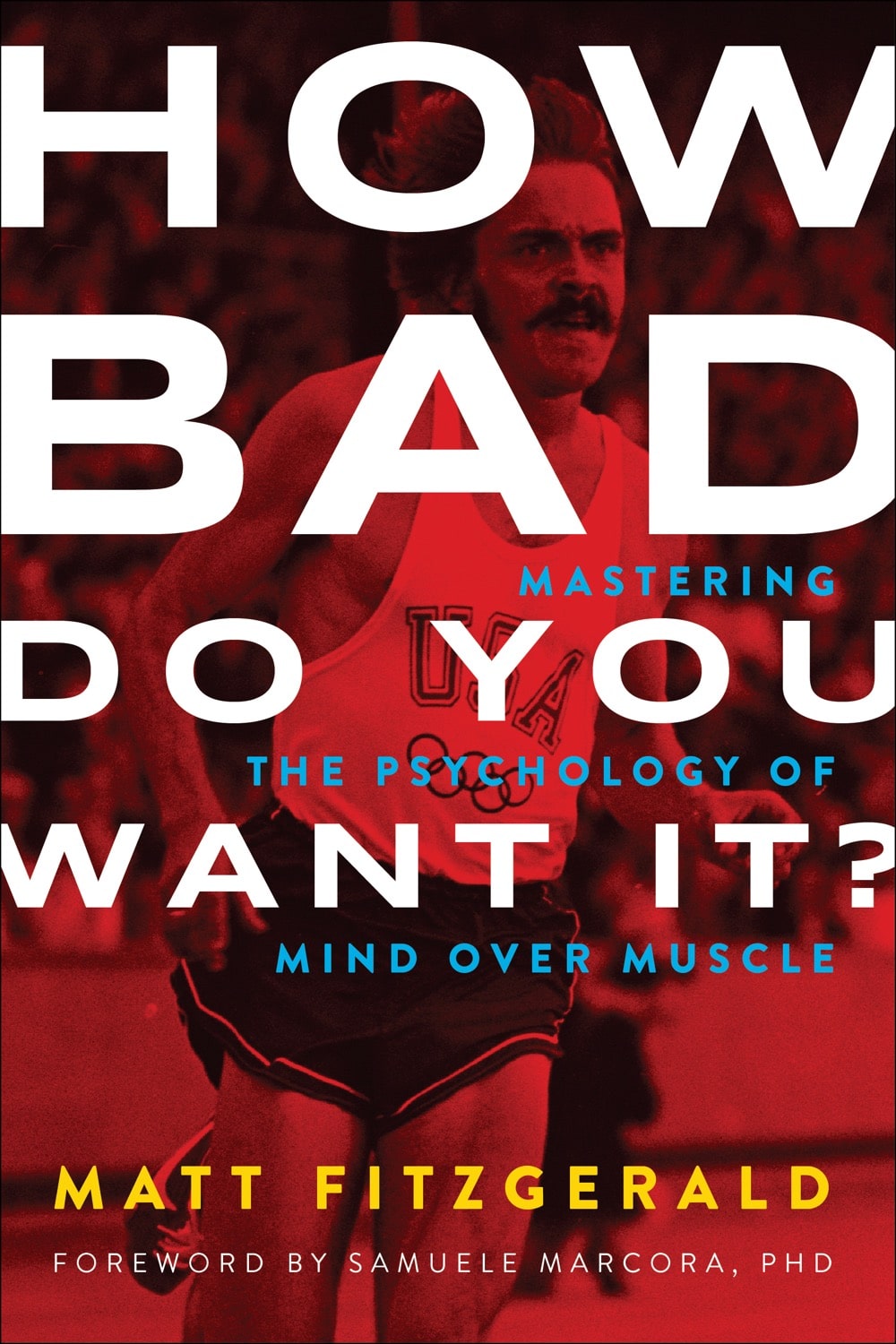

My guest today has recently published a book highlighting the exciting research that’s coming out showing that our athletic performance often comes down not to our bodies, but what’s in our head. His name is Matt Fitzgerald and his book is entitled How Bad Do You Want It? Mastering the Psychology of Mind Over Muscle. Today on the podcast, Matt and I discuss how it’s not physical fatigue that keeps us from pushing beyond “the wall” in sports, but our “perception of effort.” And how with a few psychological tricks, we can overcome this perception of how hard we’re working in order to break through plateaus and smash PRs.

Show Highlights

- The history of the science on what limits human physical performance [04:00]

- The development of the Perception of Effort model of human performance [05:30]

- How our perception of effort dictates when we slow down or back off during a run or a heavy lift [06:00]

- The research that shows the Perception of Effort model is what dictates how hard and long we go during exercise [07:00]

- The difference between perception of effort and fatigue [10:00]

- Why the “wall” during a marathon isn’t fatigue [10:30]

- Why exercise feels easy one day and hard another [12:00]

- The difference between body and brain fatigue [13:30]

- Why caffeine helps your workouts [16:00]

- Why the future of high-performance athletics will involve shocking the brain [17:30]

- Theories on why we have the perception of effort psychological tick built in to us [19:00]

- How overcoming perception of effort can allow less physically fit athletes to beat more physically fit athletes [21:00]

- Is being able to push beyond perception of effort a skill you’re born with or something you can learn? [26:00]

- How increasing your “inhibitory control” can help you move beyond your perception of effort [28:30]

- How positive self-talk can help you push yourself past your perception of effort (and how to self-talk correctly) [30:30]

- How visualization can backfire and cause you to perform worse in reality [33:00]

- What Steve Prefontaine can teach us about “embracing the suck” [36:00]

- Why focusing too much on your athletic goals can make you choke [39:30]

- Why training with a group and competing allows us to push ourselves beyond our perception of effort [45:00]

- What Matt uses to push himself beyond his wall [53:00]

Resources/Studies/People Mentioned in Podcast

- Tim Noakes

- Central Governor Model

- Samuele Marcora

- Study on how being brain fatigued leads to poor physical performance

- Transcranial direct stimulation

- Halo Neuro Headphones

- Sammy Wanjiru

- Willpower

- Study on positive self-talk

- Embrace the Suck

- Steve Prefontaine

- Study about Oxford rowers

- Behavioral synchrony

- Dig Deep, You’re Stronger Than You Think

- My 500-pound deadlift (which I used the principles I learned in this book to recently achieve)

If you’re an athlete, whether endurance or strength, and want to improve your performance in your sport, I highly recommend picking up a copy of How Bad Do You Want It? You can put the principles to work and see results immediately. It’s already helped me reach new PRs myself.

Connect With Matt Fitzgerald

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Art of Manliness Store. Check out the Art of Manliness store for AoM gear like our one-of-a-kind detective’s wallet and Ben Franklin Journal. Use code AOMPODCAST at checkout for 10% off your first purchase.

Harry’s. Upgrade your shave without breaking the bank. Use code MANLINESS at checkout for $5 off your first purchase.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. If you’re an endurance athlete, you’ve probably experienced the walls, that moment in a race where you’re pushing yourself really hard and your body just tells you, “Ya basta. Enough. You can’t go on.” You start walking or trotting.

If you’re a strength athlete, you’ve probably experienced as well. You’re lifting a weight that was super easy a week before, but now it just feels really really heavy and you can’t lift it. You think, “Maybe this is my body saying it. My body is fatigued. I can’t go on. It’s just trying to protect itself.”

What if the reality is it’s all in your mind, and that your body can actually go further and push itself harder if you could only get over that voice in your head that’s saying, “You can’t go on.”

My guest today has written a book about this research that’s coming about mind over muscle and how we can actually push ourselves beyond what we think we’re capable of by just using a few principles based in nueroscience and psychology.

His name is Matt Fitzgerald. His book is How Bad Do You Want It?: Mastering the Psychology of Mind Over Muscle. Today on the podcast, we discuss this research coming out about perceived effort and how when things feel hard, it’s actually not really hard on our body, it’s just a perception of mind that we can actually overcome. These skills are being used by endurance athletes, even strength athletes.

Today on the podcast we highlight some of these athletes who have mastered the mind over muscle. We talk about the research that backs up some of these principles that Matt talks about in his book. Even if you’re not an endurance athlete, if you’re a strength athlete, like me, who primarily lifts weights, this stuff will work for you. I’ve used some of these principles with much success in my own training. I’ve actually was able to hit a PR this past weekend, 500 pound on my dead lift using the principles from How Bad Do You Want It?

A great podcast if you’re an athlete or an amateur athlete. Without further ado, How Bad Do You Want It with Matt Fitzgerald. Make sure to check out the show notes after this new podcast at aom.is/fitzgerald.

Matt Fitzgerald, welcome to the show.

Matt Fitzgerald: Great to be here.

Brett McKay: You’re the author of the book How Bad Do You Want It? Mastering the Psychology of Mind Over Muscle. In it, you talk about the recent research that’s been coming out about how high-performance endurance athletes and even weekend warrior athletes can push themselves beyond what their body tells them they’re capable of doing.

Before we get into the recent research about that, can you put this in context? What was the history of how scientist or athletes or trainers, what do they believe was the way that the human body managed fatigued or performance, or how hard someone can push themselves? How has it changed? What’s the recent research saying about that?

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah, great question. Athletes, especially champion athletes have always known that the mind was the primary limiter. Nobody discounts the body. Running a marathon or doing an Ironman triathlon is obviously an intensely physical experience. Athletes have always understood that it just comes down to being a mental thing first and foremost.

Science has taken a while to catch up. The discipline of exercise physiology is about a century old and the original paradigm was a strictly biological one. Athletes in competition were limited by just hard physical limits, things like lactic acid production or muscle glycogen depletion. The depletion of your primary fuel source. Things like that. As physical as a car running out of gas. Game over.

Then a fellow South African researcher named Tim Noakes came along and proposed that, really, it’s the brain that limits performance before the body does. Before the body ever reaches a point of catastrophic failure, where it just can’t do anymore. There’s a protective based in the brain that doesn’t want you to basically exercise yourself to death.

When your brain receives feedback from your body, red flag indicators that you’re approaching your ultimate limit, your brain will actually unconsciously reduce output to your muscles and force you to slow down whether you want to or not.

Fast forward another 10 years. This is in the 90s when Tim Noakes proposed what’s called a … It’s called a Central Governor Model. Then this fellow who actually wrote the forward to my book, Samuele Marcora, Italian guy, came along and his theory is really that it’s true that we never are able to encounter our ultimate physical limits in endurance activities. What really limits us is not this homunculus inside your brain, pulling the strings like a puppeteer. Rather, just pure psychology.

What you do is if you hit the wall on a marathon, what’s happening is you’ve reached your tolerance for just the suffering you’re experiencing. It’s similar to pain tolerance, except it’s actually a different perception called perception of efforts. You get to this point where it’s just you’re suffering too much and you voluntarily slow down.

You’re not quite at your physical limits. You are approaching them, but you always reach that limit to just what you can consciously take. Discomfort wise first.

Brett McKay: The current model is perception of … It’s called, I guess, the perception of effort model.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yes.

Brett McKay: Is that what you’d call it?

He talked about some of the research Marcora has done to bolster this argument that he has, that it’s more psychological. There’s no central governor, our brain. It’s just that we perceive something that’s hard and we just give up because it’s hard. What are some of the research that he’s done to show that?

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah. There’s a variety of ways that experimentally you can demonstrate that at the point of absolute exhaustion or failure or giving up, athletes always have reserved physical capacity.

One interesting study that Marcora did to prove this point was that he recruited a bunch of college rugby players who are a mentally tough crowd and he had them do a three part experiment, but he only told him about the first two parts. The first part, they’ve got on stationary bikes and pedaled as hard as they could for five seconds.

Immediately after that, they had to pedal at a high but submaximal intensity as long as they could. The instructions were, “After this five seconds sprint, you have to maintain the certain power output on your bike until you just can’t anymore.”

As soon as they failed or they got in the point where they just broke down and stopped, he forced them to do another five second sprint. What he found was that, on average, the power output in that first five seconds sprint was about a thousand watts. In the second part where they were just at a high but submaximal intensity as long as they could go, their average power output was … I don’t know. Like 200 and 300 watts. Somewhere in there.

The point is, if they had truly gone to the point where they absolutely had nothing left to give and they were at their physical limit, then they couldn’t possibly, in a second, five second sprint, immediately following that point of failure, they couldn’t possibly generate anymore wattage than they had put out during that second part of the experiment. It would be like a car running with no gas. Just physically impossible.

Yet, in that second, five second sprint, which supposedly occurred by that point where they were absolutely exhausted, they put out about 750 watts. It was less than they were able to put out when they had completely fresh legs, but still about three times more than they had put out in the second part of the experiment that supposedly ended in absolutely failure.

The explanation for this is that these guys hadn’t actually done to the point of absolutely physical failure in the second part. They had simply just got into a level of suffering that they couldn’t stand anymore. When they were presented, to their surprise, with another five seconds sprint, it’s just pure psychology. They said, “Oh, well. Give seconds? That’s no big deal. I can go ahead … I can handle anything for five seconds.” They went ahead and dug in to that reserved capacity that they had hidden from themselves in that second part of the experiment.

Brett McKay: Interesting. I guess you talked in the book too just anecdotally of people who run marathons or run any type of race. They’ll hit that wall and they’ll give up and they’ll stop and start walking, but then they still feel fresh even though it felt they’re about to die. As soon as they stopped, they still feel like they had something in them. They could have kept going longer or harder if they wanted to.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah. I make that point to try and distinguish perception of effort from fatigue. Everyone knows what a perception is. It’s a specific modality through which your body interacts with the world. Thirst is a perception. Felling hot or cold is a perception. Pain is a perception, but they’re all distinct, right? You can’t confuse thirst with pain.

The idea is that effort is also a distinct perception. It’s a thing. If you talk to the average endurance athlete and you ask them, “When you hit the wall in a marathon, what are you feeling?” Most of them would say, “It’s fatigue. I slow down because I felt fatigue.”

That’s actually not the case. You are feeling fatigue, but the thing that makes you slow down is the effort perception. The way to make intuitive sense of that is to imagine, say, you are running in the last miles of a marathon and you feel both very fatigued and a very high level of perceived effort. As soon as you stop, you do feel a lot better.

I just ran my first ultra marathon of 50 miler last weekend. When I got to the finish line, I was completely gassed, but stopping felt great. Why did stopping feel great? Obviously, stopping at the end of an ultra marathon or a marathon doesn’t have any effect on your fatigue level and you’re still just as fatigued as you were when you were still running, but your effort level goes down. You just stop.

That’s really a way of showing that it’s really the effort that is making you feel so miserable. The fatigue is there but it’s not the primarily limiter in those circumstances.

Brett McKay: I guess, physiologically, you’re able to keep going. Mentally, your body is saying, “No. This is hard. Back off.”

Matt Fitzgerald: Yes. Exactly.

Brett McKay: What are the factors that increase the perception of effort when you’re running or doing other type of physical activity? I guess the things … I know I don’t do endurance events, but I lift and there are some days where everything just seems really light and easy and then the next day, I’ll do something the same weight and it just feels like hard. I’m just, “I can’t do this.”

What are some of the factors that this researcher found that affect our perception of effort?

Matt Fitzgerald: The biggest one is actually physical fatigue itself. The analogy I like to use is a jockey on a horse. The jockey is your brain and the horse is your body. The horse won’t move unless the jockey cracks the whip. That’s your brain telling your body to move.

If you have a strong fresh horse, the jockey doesn’t have to crack the whip very hard to make that horse move. If you have a weak horse or a horse that’s getting tired because it’s been running for a long time, the jockey, your brain, has to work harder and harder to make that horse keep moving at the same speed.

It really is the jockey to torture, in this metaphor. It’s the jockey, your brain, that wears out, but it’s not as if physical fatigue doesn’t matter, because your brain is just the one that’s willing your body to move. As your body gets physically fatigued, your body becomes more and more resistant to your brain’s will to move. That’s why mile 20 of a marathon feels so much worse than mile 1 even though you’re still running at the same pace. Your brain has to work harder and harder and harder to keep a tire body moving. It feels that resistance and that is what causes perceived effort to climb.

Brett McKay: Right. In the university you talked about how there’s a difference between body fatigue and brain fatigue. Sometime the jockey is tired. The body, the horse might be raring to go, but the jockey, the brain I s fatigued. How does brain fatigue influence perception of effort? How does your brain become fatigued? How does it do that in a way where it affects your performance?

Matt Fitzgerald: To be clear, because there are two schools of thought on this. The question is, “Okay. Where does perception of effort come from?” One possibility is that it comes from feedback signals from your body. Obviously, your brain is always listening to your body and that’s why you know where to put your foot down when you’re running. You’ve got proprioception and all these other perceptions, information that your brain is receiving from your body.

Maybe perception of effort comes from your brain just feeling what your body is going through. The other possibility is that perception of effort comes from brain activity itself. It comes from your brain’s efforts to make your body move. What the research is showing is that it’s actually the later. It’s the jockey, not the horse.

Fatigue that originates either in the body or the brain could cause perception of effort to increase. I already gave the example of fatigue in the body causing perception of effort to increase, because your brain has to work harder to make an unwilling body move. It can also … There is also, as you just suggested, a brain fatigue scenario.

One of the studies that Samuele Marcora did to demonstrate this was that he had a bunch of volunteers go through a mental exercise that was designed to tire out their brains before they exercise. They were just sitting at desks engaging in a challenging mental task that obviously it did not tax their bodies in any way. It just made their brains tired. Specifically, certain parts of the brain that are known to be involved with perception of effort.

After this brain fatiguing exercise, when the volunteers did a challenging endurance exercise test, they performed much more poorly when they did when they did the same test without prior brain fatiguing. There’s an example that you need a fresh brain and a fresh body if you want to be able to perform your best physically.

Brett McKay: Right. Is this why caffeine helps you have a better workout or a better training session or a better run?

Matt Fitzgerald: Yes.

Brett McKay: Stimulates the brain.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah. For a long time, when that original strictly biological model of endurance performance was dominant, people looked for all kinds of reasons why … Caffeine was known to enhance performance, but the question was why? It was proposed that it allowed the body to utilize fat more effectively or whatever.

None of that is true. All caffeine really does is … I mean, yeah. I should say caffeine does have physiological effects. The reason it enhances endurance performance is the same reason that makes you alert and lifts your mood when you have a cup of coffee in the morning before starting work.

The caffeine acts on certain parts of the brain that are involved in generating perception of effort so that when you go out and run a 10 minute mile, it feels easier than it does if you haven’t had caffeine first. It allows you … It’s just one of those things by altering the relationship between actual effort and perceived effort. It allows you to dig a little bit more into that hidden reserve than when you’re not chemically enhanced.

Brett McKay: Right. It’s interesting too to see some of the studies that’s coming out now, now that trainers and athletes understand this jockey-horse analogy and that the jockey has a lot more control. I saw this headset that you put on your head and it sends electricity through your brain to stimulate the brain before a workout to help you have a better workout.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah.

Brett McKay: I think it’s called transdermal something. I don’t know what it’s called.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah, transcranial electromagnetic stimulation. Yeah, it sounds … I’m not sure about that specific product, but that has been studied and it is in fact performance enhancing if you do it right. Tapping your brain in the right spots.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I forgot the name of the device, but you put it on your head. It’s like a pair of headphones and it just zaps your brain for 30 minutes and it’s supposed to help you perform. I guess the U.S. … The ski jump team. They’ve been using it or studying it and it’s helping out. They’re showing that it is helping. Just weird, or weird 23rd century brave new world stuff now.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah, science fiction.

Brett McKay: Right. Okay. Here’s a question I have. With the central governor model, to me that … When I first heard about it. It makes intuitive sense from, say, an evolutionary’s point, that yeah, it would make sense that our brain has this central governess as hold off, pull back, you’re about to push yourself too hard. If you push yourself even more, you might kill yourself.

I’m curious, these researchers who have been studying the perception of effort model. Have they figured out why … Is there an adaptive advantage to it? Is it very similar to the role of central governor would have in protecting our body from killing ourselves, or is there really no reason why we have this perception of effort thing?

Matt Fitzgerald: You can only really speculate. Biologists will dismiss them as folk stories. Say, “This makes sense, but that doesn’t mean it’s true.” With full awareness of that potential pitfall, Samuele Marcora has proposed that there is an adaptive advantage, and that is that … Let’s back up. The question is, “Why is exercise hard? Why does it feel uncomfortable to exercise?”

The answer to that that Marcora proposed is that it prevents you from wasting energy. Energy is a precious resource, nevermore so than in extremely primitive times. When, presumably, the earliest humans were chasing prey and fleeing predators and all that.

If exercise had no cost in discomfort, whatsoever, you could potentially have people juts exerting themselves unnecessarily and then not having any energy left for when they really needed it. That’s just it. It’s clearly why most people just don’t exercise at all today. Everyone knows that you should exercise, that it’s good for you to exercise and yet most people don’t do it because our circumstances have changed. We’re not chasing predators or fleeing prey anymore. We’re working at offices and sitting in commuter traffic.

Now, that’s become a barrier. The fact that exercise is physically uncomfortable is preventing a lot of us from doing it at all. Even though intellectually we know all the advantages.

Brett McKay: In the book you talked about there’s a difference between physical and mental fitness, and we’ve been talking about that with the jockey-horse analogy. You say that sometimes an individual with more mental fitness who has a stronger jockey can beat the person with more physical fitness. Granted we’re talking about high performance athletes here. If you are a couch potato who’s never run a 5k ever and even if you have the strongest jockey in the world, you’re probably not going to beat someone who’s been running marathons their entire life.

Can you provide some real life examples of this, of someone who they were … Physiologically, they were not as high of an athlete as their competitor, but because they had a stronger mental fitness. They’re able to beat that stronger physically fit athlete.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah. The example I give in the book is about a Kenyan runner named Sammy Wanjiru. Sammy was as physically gifted as any runner who’s ever lived. He also had a wild side. He won the Olympic marathon when he was, I think, 21 years old, maybe 23. After that he got soft a little bit. He just partied all the time and drank a lot and slacked off his training.

The 2010 Chicago marathon rolls around and the lead up to that had just been disastrous. Sammy’s coach didn’t want him to run. His manager wanted him to basically go to rehab. His training … He had been injured. His training had been spotty. He was overweight. He couldn’t keep up with his own training partners he usually demolished.

He was physically probably the best runner in the world but he rated … He also got a flu three weeks before race day. Before the race, he said, “I’m at about 75%.” That wasn’t sandbagging. Not with the truth. He ended up winning the race. It’s one of the most … I understand that for a lot of people, watching a marathon is like watching grass grow. It’s one of the most thrilling marathons I’ve ever, ever, ever watched. It was just …

Brett McKay: Hey Matt, I was going to … To your credit, when I was reading the story, how you described as like, “Wow! This actually sounds really exciting.” You did such a great job putting in the drama and letting people understand what was going on. Kudos to you for doing that.

Matt Fitzgerald: Thank you. Yeah. It was quite dramatic, especially if you knew something of the back story. Anyway, long story short. Sammy ended up squeaking out the tiniest victory and it was just plain obvious to anyone, any knowledgeable runner watching that Sammy was the weaker runner that day. If there had been exercise scientists on the scene, they could have proven that. They could have taken biopsies and such to show that, that in fact, Sammy was closer to his ultimate physical limit than the guy he beat.

There’s an example right there. Athletes know this. The champion athlete … When you’re just an average athlete like I am and you look at the champions, you just assume that it’s purely physical all the way to the top. The reason that the second place finisher finishes ahead of me is the same reason the first place finisher finishes ahead of the second place finisher.

That’s sometimes true and often the most physically gifted athlete does win, but not always because the mental side is just as important. We’re talking about small differences at that level. They can be either physical or mental that’s … Are ultimately decisive.

Brett McKay: Right. It seems to that in all domains of athletics with the … Especially in the high levels where the training, the nutrition is all on point. Everyone is pretty much doing the same thing. There’s some parody going on on the physiological level. I guess the thing that’s going to separate individuals now is the mental aspect.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah. The cool thing is that that’s the aspect that is decisive within the context, the competition itself. On the starting line, the training is done and your genes are your genes. That’s in place. The mental part plays out in real time. In every race, anyone who’s ever done any type, even if it’s just a five 5k or whatever. It gets hard. It’s almost like a life or death feeling. It can get so hard. There’s no actual wall there. You’re just basically deciding at every point of the way, “Am I going to push harder or am I going to pack it in?”

It’s an acquired taste, but that’s what keeps so many of us coming back for more, is that it’s a real compelling test of your mettle.

Brett McKay: Yeah, masochist. It’s artificially those ultra marathon guys.

Let’s talk about this. If we can train ourselves to push ourselves beyond what our perception of effort thinks we’re capable of doing. Before back up. There are some athletes who are able to do this. Who are able to push themselves beyond what they think they’re able to do or what their perceived effort is. I’m curious, is this an inborn skill or is this something that can be developed as well?

Matt Fitzgerald: I would say it’s definitely both. Just like the physical side, you’re not going to be an Olympic champion unless you win the genetic lottery. No matter what kind of genes you’re born with, that alone ain’t going to do it. You have to work your tail off and make smart decisions in how you develop as an athlete.

The same thing is true on the physical side. Because it’s really your personality actually that decides whether you’re mentally fit or not. That’s why it’s not always the same formula for every athlete. For some athletes, take that Sammy Wanjiru example. He had a reckless personality, but it was his recklessness … He actually died at age 24 by the way. Fell off a balcony in a drunken stupor.

The same recklessness that led to his early demise was a great advantage on the race course. That doesn’t mean that every great endurance athlete has a reckless freak. For some people, like Louis Zamperini, the guy that the Unbroken movie was made about. For him, it wasn’t recklessness, it was unbridled optimism. The same characteristic that allowed him to survive as a prisoner of war in Japan in World War II was what made him a champion endurance athlete.

Obviously, personality is largely something that you’re born with. The good news is you can also develop these probing skills or these mental fitness traits. One of them is known as inhibitory control. Inhibitory control comes into play anytime you want two things simultaneously that are contradictory. You can’t have them both.

The example I always like to give is you want to lose 10 pounds, but you want that piece of German chocolate cake sitting in front of you. You can’t have both. You’re divided and your brain has to decide which one you want to choose and stay focused on. It’s easier to understand how inhibitory control matters on a race course, because you get to a point in a race where you want to finish and achieve your goal, but at the same time you want to stop suffering. YOu’re getting pulled in two directions and you have to decide, “All right. Which thing do I actually want most?” It takes a skill called inhibitory control to do that.

There are tests of this, of inhibitory control. You sit down in front of a computer and you’re required to make these choices. Some people are better at it than others are, but it is trainable. You can get better at it. In fact, one of the ways to get better at it is to get in shape, because when you train, physically train, you’re confronted with that desire to quit and end your suffering all the time. Day after day, you make the decision to get going. That alone will actually enhance your inhibitory control.

Brett McKay: Yeah, it increases your will power to make the right choice. Before we get into some of these other coping skills, is this … And with all of them. Do you have to train them within the context of the sport or exercise that you’re doing? Can you do things that train that coping skill outside of the event and that it will carry over to endurance, your race for example. Does that question make sense?

Matt Fitzgerald: Yes. Anything that happens in your life that affects your psychology could end up affecting you as an athlete. For example, it couldn’t be just like a struggle you go through in your personal life that tests you and strengthens you. It could have that struggle, personal struggle, might have nothing to do with athletics. You only have one brain, so the same psychology that you apply in your personal life, you’re going to apply in the race course too. Something you go through like that could end up making the better athlete.

You can also proactively choose ways to enhance your mental fitness off the race course or off the training grounds. One of them … Again, to cite a study that Samuele Marcor did is positive self-talk. The idea is that it’s like the engine that could, I think I can. I think I can.

Anytime you start to struggle with fatigue and perception of effort, you’re going to think negative thoughts. It’s impossible to stop them from coming. It’s been shown that if you train yourself to arrest those thoughts early and replace them with positive alternatives, it’s actually performance enhancing. Marcora did a study that proved that.

It’s actually a fascinating study, because you took a bunch of non-athletes and you had them do the usual e endurance test before and after. After the before the test, half of the subjects were trained in positive self-talk and the other half were not. When the test was repeated, those who got the positive self-talk training performed way better, like 20% better in the same test. Obviously, there was no improvement in the control group.

What’s amazing about that is that there was no physical exercise involved at all. It was a physical endurance test that they improved on simply through a purely psychological intervention, which is cool.

Brett McKay: What is the self-talk look like? Do you just tell yourself, “I think I can.” or do you say, “You got this?” What is it that you’re supposed to say to yourself?

Matt Fitzgerald: I don’t know the details of exactly what Marcora did, but any experienced athlete, as I am, learns what it means from you. Generally, the way it works is you get to a point where you’re struggling and then you have a negative thought. Instead of just allowing that to happen, you step back from yourself and realize you’re having a negative thought and you just consciously stop it and replace it with something else.

What I found is that, that something else is different for different athletes. The thing that works for one might now work for the other. You can try to give people a one size fits all thing to go into. That could help somewhat. Ultimately, what I’ve found is that in those moments of crisis, your brain gets really creative, because you’re looking for lifelines, psychological lifelines.

It’s interesting to see what you come up. I tell athletes, “When you find something that works for you. Remember it. Because then you can come up with your own formula and go in better armed the next time around.”

Brett McKay: What I thought was interesting, with all these coping skills you discussed in the book and we’ll talk about more in a bit. Visualization was one that yous aid that really doesn’t work or it can even backfire. That’s been an article of faith in sports psychology, that you’re supposed to … The athlete is supposed to take time. If you’re a quarterback, you’re supposed to lay down and imagine the game and imagine yourself going through a tough situation and then seeing how you would respond in very detailed descriptions. Why is it that visualization can sometimes backfire in helping you manage perceived effort?

Matt Fitzgerald: To be clear, when done right, visualization or mental rehearsal as it’s sometimes called, does work or can work. It’s often done wrong and that’s when it can backfire. What you don’t want to do with visualization is be unrealistic and imagine a pie in the sky perfect race scenario, because guess what? That race ain’t going to be perfect.

I talked about an example of an athlete in the book. A world champion triathlete named Siri Lindley who made exactly that mistake. She was training to qualify for the first Olympic triathlon and she was considered … She was one of the best triathletes in the world. She was the best American. She was considered a shoe-in.

What she did is every night, starting one year before the Olympic trails, she would visualize the perfect race. Over and over again, it was the same. She got off to a great start and she was following the world champion and swam and so on and so on.

When the trials come around, right way, something went off script. She ended up just getting dunked underwater and swam over the top off during a swim which was not part of her rehearsal and she panicked. She ended up not even finishing the race. Not for any physical reason, but just because she lost her cool because her visualization had set her up for a failure.

That’s what you want to avoid. The proper way to use visualization is to make it as realistic as possible. You want it to be positive. You want to picture yourself performing well. You want to imagine the struggle that you’re going to go through. You want to imagine it being hard on the way toward a successful outcome.

Brett McKay: This ties in with the first coping skills you talked about in the book is the idea of bracing. Just accepting the fact that it’s going to be hard. That can do a lot to help you push beyond your perceived effort.

Matt Fitzgerald: Exactly. I should explain that. Perceived effort has two layers. At any given point, when you’re doing a race. The first layer is just how you feel. You can’t do anything about that. If you get 20 miles into a marathon, to go back in the same example. How you feel is how you feel. You just got to that point and it is what it is.

There’s also a second layer which is how you feel about how you feel. That you can do something about. You can … With any given level of suffering or effort you’re experiencing, you can have a bad attitude about it or a good attitude about it. It’s a matter of you interpret it.

What research shoes is that if you maintain a good attitude or a positive interpretation of how you’re feeling no matter how bad you actually feel. You will be able to squeeze a little bit better performance out of yourself.

One of the things that affects how you feel about how you feel is prior expectations. If you get halfway through a race and you’re suffering more than you expected to, you’re more likely to have a bad attitude about how you feel and perform worse. That’s where bracing comes in.

Bracing sounds like pessimism. Basically, the idea is before a race, you should be telling yourself this is going to be hard. This could be the hardest thing I have ever done. That’s not really pessimism, because you’re not saying, “I won’t perform well. I want to achieve my goal.” You’re just setting yourself up to be ready for any amount of struggle you might experience.

If you equip yourself in that way before you go into the race, then you’ll never be surprised by how bad you feel and you’ll always have a positive attitude as you possibly could about how you feel and you won’t be hamstrung psychologically I your performance.

Brett McKay: This is why you talked about in the book Prefontaine, the great distance runner. Before he runs, his teammates had always talked about how you just become a grouch and say, “I don’t want to do this. I hate running in the cold.” Then you’d go on and perform wonderfully.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yes. Yeah. That’s exactly what he was doing there. He did it instinctively. It was just something did perhaps not even knowing why. Obviously, it worked. He was known as one of the grittiest, toughest runners of his generation. That was part of his formula. You have to say, “This is going to suck. I don’t even want to be here.”

I think it might have served two purposes for him. One would be bracing. The other would just be to take a little bit of the pressure off of himself, just relax. It’s almost like letting himself off the hook a bit just so he could get to the point … So he wouldn’t freak out before the gun went off. When the gun went off, he was fine. He just had to get to that point. He just used his own recipe to get there.

Brett McKay: It helps prevent chocking, which you talked about in detail in the book. Going back to Siri Lindley. That’s the coping skill that she use is letting go of. She was gung ho about winning the Olympic triathlon. For some reason, she got this coach that told her, “No. You just got to let go of that goal.” It ended up counter-intuitively helping her reach that goal.

Matt Fitzgerald: Exactly. It’s funny, someone who just read this book sent me a Tweet with a Bruce Springsteen quote in it that this reader was reminded of by that exact episode there. Basically, what Bruce Springsteen said is, he said, “When I go on stage, I feel like I can’t perform the way I want to unless I feel like it’s the most important thing in the world.”

Yet, he said, “I also can’t perform the way I want to unless my attitude is, “You know what? It’s just rock and roll.” He said there’s a balance there where he’s mentally in two very difference places at once, like, “This is super important. I need to take this seriously.” At the same time, “Hey, you know what? It’s not the end of the world if a string breaks or whatever.”

That’s exactly it. That’s the attitude you have to have as an athlete where you want your goal very badly, but at the same time, you’re loose. What can happen is sometimes, and it especially happens to athletes like Siri who have confidence issues or insecurity issues, is that their goal would come something that they can’t live without at achieving. The idea is, “If I don’t achieve my goal in this race, I’ll hate myself. I won’t think I’m a good person. I’ll think I’m a bad athlete.”

Champions, actually, they don’t have that attitude. They’re actually more likely to make excuses. Their attitude is, “I already know I’m great. I want to achieve this goal, if I don’t, it’s because my shoes suck or because the weather was bad.” Actually, it sounds like immature, but it’s actually a healthier attitude. It’s more likely to help you perform. You have goals and you want them very badly, but you have a lose grasp on them. Your goals aren’t determining how you feel about yourself. That’s exactly what prevents you from chocking. You go into competition less self conscious and you’re allowed to just immerse yourself in what you’re doing and just …

In ball sports, it’s always referred to as looseness. Which team is looser going into the Super Bowl or whatever the championship game is. That’s exactly the same phenomenon. It’s not that they don’t care, but they just care in a way that’s more likely to actually have a positive outcome.

Brett McKay: I’m curious about the research about working out or training or competing with a group that allows us to push ourselves beyond what we thought we’re capable of. I think a lot of people think of, particularly, endurance sports, running, as individual sports. Just about the single lone athlete.

You argue that there’s an actual social component going on there that these individual athletes use or harness to push themselves beyond perceived effort.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yup. Human beings are social animals. We behave differently in groups than we do alone. That includes when we are testing our endurance performance capacity. Just to make this concrete, there’s an example that I describe … A study that I described in the book involving rowers, where a group of rowers were asked to do an indoor rowing workout on two separate occasions. There were eight of these guys that were Oxford University’s elite level of rowers.

They did the performance test on indoor rowing machines alone, and then all together in a group of eight. It was exactly the same workout, they just did it alone and together. After both of those tests, they were subjected to a test of pain tolerance. It was found that their pain tolerance was significantly higher after they had done the workout as a group.

The authors of the study speculated that that was because when the rowers did the workout as a group, their brains released more endorphins which are the runners high neurotransmitters which just … They just elevate your mood. They also would elevate your pain tolerance.

Perception of effort is a different perception than pain, but they’re pretty much parallel. Anything that’s likely to increase your pain tolerance is also likely to increase your tolerance for perceived effort.

This phenomenon is referred to as behavioral synchrony. If you’re chopping wood, you can chop more wood if there are eight guys around you doing the same thing. If you’re running a marathon, or more importantly, if you’re training day in and day out with a group of athletes, you’re more likely to just be able to push harder, dig deeper and make more progress than if you’re always out there alone.

Brett McKay: Right. Maybe, that’s one of the geniuses of crossfit, where it’s very social. You have a box. You have these people there, they’re pushing you or you’re maybe competing against them in a positive way to push yourself beyond what you thought you’re capable of.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah. Just to add on to that. There are actually two things going on there. There’s behavioral synchrony and there’s competition. You can benefit from both. Sometimes it can be hard to separate them, but you actually can do that so you can benefit in both ways. Part of it is competitive, but part of it is also cooperative.

That’s why … That’s one the reasons that not just exercising with other people’s performance enhancing, but simply being observed by other people while you’re exercising is performance enhancing. If you know people are watching and seeing how well you’re doing, you will also be able to perform better even though you’re not in competition with the people who are simply observing you.

Brett McKay: Interesting. I’m curious Matt that your book is focused in endurance athletes. Can come of these coping skills work with strength athletes, whether they’re weight lifters or shot putters or that sort of athlete?

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah. I would say that the coping skills, the framework that I described in the book, it’s relevant to any athlete or exerciser who experiences fatigue. I think that’s everyone. Even if you do a set of barbel squats, there’s a reason the 10th one is harder than the first. You’re dealing with fatigue, even though it’s a very high intensity and short duration activity.

If you are pushing up against fatigue and its effects on your perception of effort, then these coping skills can help you perform better. One specific one, just to give you a very concrete example is, and one we haven’t really discussed yet is this idea of internal versus external tensional focus.

There are basically two directions you can focus your attention during exercise. You can focus it inward, like thinking about how your body is moving or thinking about how hard you’re working. You can focus it externally, sort of on the task at-hand. It’s like, “Where is my competition?” or “Am I maintaining my pace?”

There’s research showing that an external focus of attention, just keeping your tension on the task, versus hyper-focused internally is performance enhancing in everything, from weight lifting, to skill sports, to endurance sports. It’s exactly the same skill, but it’s beneficial, and you name it. Any sport, any type of exercise you can name, it’s beneficial.

Brett McKay: Yeah, the whole external, internal focus. I use that, now that you mentioned it, in high school foot ball when we did gassers and wind sprints.

I remember there was a time where it’s like, “I can’t do this.” I would just pretend like I wasn’t inside my body. It was weird, but it worked. I was able to push myself. I just didn’t … I don’t know. I looked at myself from the outside and that, for some reason, worked for me.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah. That’s called dissociation.

Brett McKay: Okay. Had dissociated. Not knowing that I dissociated.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah. That’s another one. Yup.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Just you know, from a strength perspective. We were talking earlier before we started the interview. While I was reading this book, I started using some of the coping skills with my own strength training and it helped out a lot. The ones that worked for me were bracing. Just accepting that this is going to suck. It’s going to hurt.

The other thing that just helped me, it’s reminding myself that my body is capable of pushing this weight up. Even though I might not think it is. There’s enough in my physiologically that I can do it. For some reason, that helped as well.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah. Yeah. I’m not surprised to hear that. It’s really a lot of fun. You’re just … Obviously, lifting weights, it’s very physical, but it can also be intellectually stimulating as well. If you start to just actively pursue the development of your mental fitness, whether it’s an endurance athlete, or a weightlifter, or whatever. It just adds another layer to the experience.

For me, I’ve been a runner my whole life and a triathlete, but I’m in my mid-40s now. I’m not getting faster, but I’m still just engaged in continuing as an athlete because the journey never ends. You can still get better and better and better at the psychological side even as your body gets older.

Brett McKay: What do you do? We talked about these different coping skills and it seems like there’s some of it that you had to … You do it as you’re going along in your training and you develop these coping skills. Is there one coping skill that a lot of athletes just turn to when they’re in that [meat 00:52:17] moment, the heat of the moment in the race and their body just … Their body says to them or it thinks it’s saying to them, “You can’t go any further. Ease up. You’ll get it next time.”

How do you dig deep in that moment when you hit the wall? Do you just have to ask yourself that question, and that’s the title of your book, “How Bad Do You Want It?”

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah. Great question. It’s interesting. My book has been very well received, but one of the criticisms I’ve gotten from some people is that there are some readers who wanted more handholding. They wanted like, “Just do these five things.”

Brett McKay: Yeah, everyone wants that. Right.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah. You will be a mental giant. I understand that, but actually part of what I love about the sports I do is that that’s impossible. That what I can provide is just a different way to approach the sport. A different way to understand what you’re doing. Which I think is actually extremely helpful. What I can’t do is say, “just do this.” I like that. I like that. After a certain point, you’re on your own. You just are.

Especially when you get to that crisis moment in a race or whatever where you want to pack it in. You’re suffering a lot. There’s just no telling what is going to allow you to keep going. It’s not as if it’s completely different for every athlete. Obviously, there are patterns.

To give you example of that 50 mile ultra marathon I did last weekend. I suffered vitally. I remember getting to one point in the race where I remembered what a friend had said before the race. I actually had an injury going into the race and I wasn’t sure I would even be able to do it.

His advice was, “Be grateful for just being able to at least start and try.” I just remembered that. It just came to me. It’s not as if I had a plan. It’s like, “Oh, yeah. When I get to 37 miles I’m going to remind myself be grateful.” Most of our mind is underwater. It’s the part of the iceberg that’s below the surface. That’s where creativity comes from. It’s where where so many of the answers come from. It’s like stuff is being handed to you from behind a curtain. You can’t control that, but you can trust it.

When you get to one of those moments and it just comes to you, it’s right. You can set it up ahead of time, like, “Oh, I’m going to script out my entire 50 miles.” No. You have to be reactive just as you do like in a basketball game. It really helped me to just remind myself, “You know what? I’m really suffering here, but I am going to finish this thing and I am super grateful just to have this opportunity to be able to do this and it made a difference.”

I’m sure for the other 700 athletes out there racing with me, there wasn’t necessarily that, that allowed them to get over the hump as it were.

Brett McKay: Right. You’re on your own. You got to figure it out yourself, what works for you.

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah. Just to add one other thing. Let’s get back to your original question, the how bad you want it question. That’s the motivation piece and that is very helpful as well. When you start to struggle, to reconnect with why this is important to you can be extremely helpful. Again. It’s going to be important to different people for different reasons. There’s no one size fits all there either.

On a general level, it’s the same for everyone. The more you’re able to just reconnect and remind yourself why you want it badly. Why you want to achieve your goal and make it to the finish line. Whether it’s to set example for your children or if it’s just … Maybe you were a child who is completely un-athletic. This is a second chance for you to just connect with your physical side. Whatever it is.

Those are powerful motivators, because you … It takes a lot of hard work to do the training to get to these events. Obviously, there’s something driving you, and to not lose that in the heat of the moment, can be another one of those factors that helps you survive.

Brett McKay: Matt, this has been a fascinating conversation and we just skimmed over a lot what’s in the book. There’s a lot more that our readers can dig into. Where can people learn more about your book?

Matt Fitzgerald: Yeah. The best place to start would be my website probably which is mattfitzgerald.org.

Brett McKay: Okay. Matt Fitzgerald, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Matt Fitzgerald: You bet. I really enjoyed it.

Brett McKay: My guest there was Matt Fitzgerald. He’s the author of the book How Bad Do You Want It? It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can also find out more information about Matt’s work at mattfitzgerald.org.

Be sure to checkout the show notes for this podcast at aom.is/fitzgerals where you’ll find links to resources we mentioned in the podcast where you can explore this topic in more detail.

That wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoy this podcast and have gotten something out of it, I’d really appreciate it if you’d give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher and help spread the word about the show.

As always, I appreciate your continued support. Until next time. This is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.