The topic of health and fitness has long been a popular one for magazines, and in most recent times, for blogs and Instagram accounts. But what these modern publishers and influencers probably don’t realize is that they’re standing on the shoulders of an ambitious eccentric who laid the foundation for much of modern American media: Bernarr Macfadden.

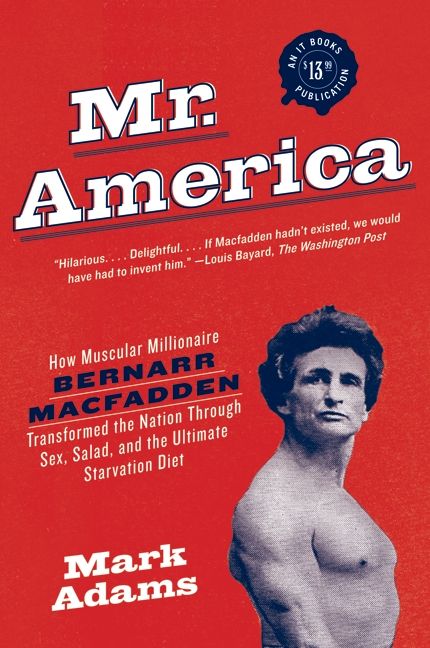

My guest today is Mark Adams, who wrote a biography of this proto fitness guru called Mr. America: How Muscular Millionaire Bernarr Macfadden Transformed the Nation Through Sex, Salad, and the Ultimate Starvation Diet. Mark and I begin our conversation with how Macfadden discovered a passion for health and fitness as a young man and failed at his attempt to become a personal trainer, despite coining the motto “Weakness is a crime; don’t be a criminal.” We then discuss how Macfadden went on to start the highly successful magazine, Physical Culture, and then an entire publishing empire, which pioneered many of the confessional, first-person, personal branding techniques still used today. Mark shares the tenets of Macfadden’s sometimes sound, sometimes wacky health philosophy, including his advocacy of fasting, and what happened when Mark tried out some of Macfadden’s protocols on himself. Mark and I then delve into how Macfadden founded a utopian community in the New Jersey suburbs, was convicted of obscenity charges, trained fascist cadets for Mussolini, and ran for U.S. senator on a physical fitness platform. We end our conversation with why Macfadden was forgotten, and yet had a lasting effect on the world of health and fitness, as well as media as a whole.

If reading this in an email, click the title of the post to listen to the show.

Show Highlights

- Bernarr’s tough early childhood

- How Bernarr was then exposed to innovative ideas about health and medicine

- Bernarr’s marketing genius

- The old-time strongmen of Macfadden’s time

- The success of Physical Culture magazine

- Bernarr’s bizarro health ideas

- How he ushered in a few modern popular health ideas

- What happened when Mark tried a few of Bernarr’s protocols

- How Macfadden jumpstarted America’s sex ed

- Macfadden’s publishing empire

- His foray into politics and his new political party (and his strange connection to the Roosevelts)

- Why was Bernarr forgotten? What’s his influence on modern fitness culture?

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Modern “Neurasthenia”: Curing Your Restlessness

- The History of Physical Fitness

- Eugen Sandow, Victorian Strongman

- The Ultimate Guide to Oldtime Strongman Fitness

- Odd Exercises for Physical Vigor

- Macfadden’s Encyclopedia of Physical Culture

- The Pros and Cons of Intermittent Fasting

- Joe Weider

Connect With Mark

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. The topic of health and fitness has long been a popular one for magazines and in most recent times, for blogs and Instagram accounts. But what these modern publishers and influencers probably don’t realize is that they’re standing on the shoulders of an ambitious eccentric, who laid the foundation for much of modern American media. His name is Bernarr Macfadden. My guest today is Mark Adams, who wrote a biography of this proto fitness guru called Mr. America: How muscular millionaire Bernarr Macfadden transformed the nation through sex, salad, and the ultimate starvation diet. Mark and I begin our conversation with how Macfadden discovered a passion for health and fitness as a young man and failed at his attempt to become a personal trainer, despite coining the motto “WEAKNESS IS A CRIME, DON’T BE A CRIMINAL.” All in capital letters.

We then discuss how Macfadden went on to start the highly successful magazine, physical culture, and then an entire publishing empire which pioneered many of the confessional first person personal branding techniques still used today. Mark shares the tenets of Macfadden sometimes sound, sometimes wacky health philosophy, including his advocacy for fasting and what happened to Mark when he tried out some of the Macfadden’s protocols on himself. Mark and I then delve into how Macfadden founded a utopian community in the New Jersey suburbs, was convicted of obscenity charges, trained fascist cadets for Mussolini and then ran for US senator on a physical fitness platform. We end our conversation with why Macfadden was forgotten and yet had a lasting effect on the world of health and fitness, as well as media as a whole. After the show is over, check out the shownotes at aom.is/macfadden. Mark joins me now via clearcast.io.

Alright, Mark Adams, welcome to the show.

Mark Adams: Thank you for having me, Brett.

Brett McKay: So, over… It’s been over 10 years ago, 12 years, you wrote a book called Mr. America: How Muscular Millionaire Bernarr Macfadden Transformed the Nation Through Sex, Salad, and the Ultimate Starvation Diet. And this is about this icon of the physical fitness movement that started in America, really, the late 19th century, early 20th century. We’re gonna talk about this guy today, but how did you go into a deep dive on the history of this guy that a lot of people haven’t even heard of?

Mark Adams: Well, in the late ’90s, I was named fitness editor of GQ Magazine. And as many magazine editors do, I went to some old magazines in a thrift store looking to steal ideas. And I came across a stack of physical culture magazines. I was not familiar with the title at the time, opened it up, and in these magazines from the 1920s, there were stories about reversing heart disease through exercise, there were stories about yoga, there were stories about intermittent fasting. And I was like, What is this magazine? I’ve got to look into this. And the more I looked into it, the more I learned the story of Bernarr Macfadden’s life, the more I realized that there was at the very least, a book, if not a movie, miniseries inside this man’s life.

Brett McKay: See, we were earlier talking about some of his exploits, because we were talking earlier, it’s like you read his story, and you’re like, this can’t be real because he did so much in his life, and he had a huge impact on Physical Fitness that we still see today and we’ll talk about that, but beyond that, he had a huge impact on the publishing industry, the magazine industry. And you can even say he’s sort of a predecessor for blogs or Instagram influencers as well.

Mark Adams: Oh, without question. He is the progenitor of all reality television, all personal branding, all of that sort of thing. He’s the man who really got all of that off the ground about 100 years ago.

Brett McKay: But you know, the title of the book is Mr. America, and this guy is… Like, he’s the American story. He’s like the Horatio Alger story. He had a really tough childhood growing up in post-Civil War Missouri, basically an orphan. His dad died and he was an alcoholic. Mom was so poor that just kind of shipped him off to some family members and had a really hard life, but at what point in his childhood did Bernarr discover physical fitness?

Mark Adams: So he is sent off to this… His mother called it a boarding school, but it was basically an orphanage, for a couple of years. After that, he’s sent into what is essentially indentured servitude with some relatives. And then [chuckle] a guy who the relatives gave him to, a farmer for a couple of years, and he’s working just for room and board, and they traded… I think the New Yorker called it a scattering of mixed produce, for this boy. And it’s only at the age of 15 or 16 that he, for the first time, meets some family members who are actually glad to see him. And he goes to St. Louis, which at the time is a boom town. St. Louis is a conduit for German immigrants into the United States. This is a time when German is still required in St. Louis Public Schools, and the Germans bring with them, this traditional of social physical fitness. They called it Turnverein. And Bernarr Macfadden walks into the St. Louis gymnasium one day after work with his uncle and discovers guys performing acts that are like gymnastics, we would call it now, working with ropes and pulleys and Pommel Horses and that sort of thing. And he’s utterly mesmerized, and from that day forward, he commits himself to physical fitness and that’s the rest of his life essentially.

Brett McKay: And these German gymnasiums is really interesting, it’s an interesting part of fitness culture in America, because not only were they… Were you there to build your body, but they had like a reading room where you’d go and you can read and discuss philosophy and play chess.

Mark Adams: Yeah. Well, it’s interesting, because this is a moment in American alternative medicine where the area around Missouri is like cutting edge, this is the wild west. So, you’ve got the Germans bringing hydropathy, which is like hot and cold baths, sweats, enemas. And then you’ve got osteopathy being created right around this time in that area. You’ve got chiropracty being invented right across the border in Iowa, just up from St Louis. So this is a really interesting time. The Germans also brought homeopathy, and this is also a moment when Americans are starting to move from the farm into big cities, and there becomes this sort of national panic that, basically, American men are becoming a bunch of wussies, because they’re not working on the farm anymore. They start suffering from what was called neurasthenia, which is like a nervous condition, where you sit at a desk all day, and you get weak, and then you start shaking, and you’re not really a manly man anymore. And Macfadden is reading about this stuff at the German gymnasium, the St. Louis Gymnasium that he goes to. And in particular, he comes across a book by William Blakey, who is a Harvard teacher. And he’s essentially saying, “If you lift heavy things and get cardio exercise, you will be in amazing shape, and you will never get sick.” And this is like a magic charm for Macfadden, and he carries that book with him the rest of his life.

Brett McKay: So basically, there was just… In this gymnasium, he was exposed to all these different… These new ideas that were percolated in Western culture, particularly in America, with different alternative medicines. Because at the time, a lot of people were seeing professional doctors as corrupt. And in fact, this is the time when… This is before the medical industry, where there is any sort of standardization or ethics. I mean, you could just be a doctor, and I think a lot of people mistrusted that.

Mark Adams: Now, this is the era of patent medicines, you know, snake oil, medicine shows. The AMA, the American Medical Association, is not organized until, I think, the second decade of the 20th century. So, if you wanted to call yourself a doctor at this time, you could call yourself a doctor. And a lot of it was quackery, and this had a great impact on Macfadden, especially because, as a boy, he was vaccinated against smallpox, which at the time meant that you would have a lesion from someone who’s suffering from smallpox, and they would take some of the pus and then cut open your arm and rub some of the pus in there, and then you would get like a low grade, you know, a version of smallpox, and that would be your vaccination for the rest of your life. And Macfadden had that happen, was in bed for months and months as a child, and never forgave doctors, and never trusted them again for the rest of his life.

Brett McKay: Yeah, he got blood poisoning.

Mark Adams: He got blood poisoning, essentially, yeah. I mean, it’s a barbarous form of medicine, but Macfadden… His mind never moved forward from the 1880s, as far as doctors were concerned.

Brett McKay: And that sort of… I mean, he became an anti-vaxxer, basically, for the rest of his life. That experience he had as a boy influenced what he thought about medicine, or particularly vaccinations, going forward, and what he wrote about later on in his career.

Mark Adams: Oh, yeah. I mean, he wrote up a list in his magazines of the seven great enemies of American society. And one of them was doctors and vaccinations. When he started publishing a newspaper in the 1920s, you may remember [chuckle] the Disney movie about Balto, the Husky who runs across Alaska to get this important serum to Nome, so that people can be rescued from diphtheria. So, every newspaper in America is covering this heroic run. Town by town, this dog-sled team is going across Alaska, Macfadden’s newspaper is covering it as some sort of tragedy. [chuckle] He’s talking about how this is a public relation scam, put together by what he calls the Post Trust. So yeah, he never really comes around to any sort of medical… What at that time was known as chemotherapy, any sort of medicine involving chemicals.

Brett McKay: So, besides these new alternative medicine things that were popping up, in the physical culture scene, this is when people actually started taking physical fitness serious in America. Before that time, people… Exercise is mainly for like soldiers, and then I think there was references to Ben Franklin using Indian clubs or dumbbells.

Mark Adams: Yes.

Brett McKay: But this… Yeah, this period, this is when people… Americans were like, “No, exercise is a thing you do, separate from whatever else you do in your life.”

Mark Adams: Right, this is like the rebirth of the old Greek ideal of “mens sana in corpore sano.” I guess that’s Latin, but anyway, it comes from the Greeks, Hippocrates and all that. Keep your body sound, and your mind will follow. And we take that for granted now, but up until the 1870s, 1880s, everybody was working so hard physically, that they didn’t really have to worry about this. As industrialization comes in, the YMCA is invented over in Britain, people start worrying about America’s youth, and it becomes a major issue. People are worried for national security reasons, that Americans are just becoming a bunch of slovenly [chuckle] trolls, who won’t be able to fight in a war, if it comes up. And this is an obsession of Macfadden’s that comes up again and again over time.

Brett McKay: So, as a teenager, he’s going to this gymnasium in St. Louis, this German gymnasium, and he’s soaking in all this stuff, and formulating a philosophy of physical fitness that he ends up calling physical culture. But when did he start seeing himself not as a student, but as a teacher of physical culture, like, when did that happen?

Mark Adams: Around 1891, Macfadden has worked for his uncle for a while, moved around the Midwest, worked at a couple of schools, as essentially like a football coach, athletic director. And he hangs out his shingle as what he calls a Kinestherapist. It’s a coinage of his own, it means “person who cures using exercise.” He’s what we would now call a personal trainer. And he comes up with the great slogan of his life, which is, “WEAKNESS IS A CRIME, DON’T BE A CRIMINAL.” [chuckle] So, he’s got the package down, he’s working on the marketing, but in St. Louis, in 1891, he cannot find the audience. And what happens is, in 1893, he goes to the Columbian Exposition, in Chicago, the Great World’s Fair, and sees a performer named Eugen Sandow. Sandow is a German, in the 1890s he is one of the most famous men in the world.

He’s a strong man. He performs around Europe and the US in poses, he dusts himself down with chalk, and he stands in front of a black cabinet, and shows off. He’s got an extraordinary physique, it’s easy to find photographs of him. And he performed stunts like, there will be two draft horses in baskets, and he will put a beam between them, and then lift the two draft horses on his back, on stage. He does that sort of thing. So, Macfadden sees this, and he realizes that if he can imitate Sandow’s posing, and show off some incredible stunts of his own, he might be able to sell this exercise machine, this sort of proto-nautilus machine, with pulleys that you attach to your wall, and barnstorm around the US and make some money that way. Well, it doesn’t work out in the US so he goes to England where Sandow was living and it’s a huge success. While he’s in England, he sees that Sandow has started a magazine called Physical Culture. And Macfadden essentially steals Sandow’s idea, comes back to New York and decides to do a much better version of his own.

Brett McKay: Yeah, the Sandow… We’ve had a podcast about Sandow before. I mean, that was another interesting phenomenon, because this is where… Yeah. He basically almost got naked, basically had like just a leaf there and did these poses.

Mark Adams: Yeah. Yeah. And there’s so many pictures of him. He’s so strong, he’s got this enormous chest. And when I went down to the University of Texas, which is where the world’s biggest physical culture library is located, I asked them, I said, “How come guys around this time are… They’re huge in their legs, they’re huge in their arms, they’re huge in their traps and deltoids but their chests aren’t as big?” And the guy told me, Terry Todd, the professor told me, “Well, the bench press hadn’t been invented yet.” The bench press wasn’t invented until the 1930s, 1940s. So, the fact that Sandow was able to get this big before the bench was invented is just extraordinary to me.

Brett McKay: I thought one of the funniest parts from Sandow’s history… So he’d do these performances but then afterwards he had private performances where people would get up close and touch him. And women would literally faint. Like, the 19th century lady would faint and you had to do the smelling salts thing.

Mark Adams: Totally.

Brett McKay: It’s just… For some reason, I think that’s funny. So yeah, basically he sees Sandow doing this, does Sandow’s thing, takes it back to America, starts Physical Culture magazine. This is the thing that made him into a publisher. What kinda stuff was he writing about in Physical Culture?

Mark Adams: You know, he’s writing about his two great ideas in life, neither of which were original to him, but which he found a way to broadcast to a bigger audience where Americans eat too much and Americans don’t exercise. So, he got that point across. But what he did differently, that made his magazine an instant success was, first of all, he wrote in a very personal voice. Some of the great magazines in American history, things like Playboy, Rolling Stone, Martha Stewart Living, they were successes because they’re all about the passion of the founding editor. Hugh Hefner, Jann Wenner, Martha Stewart. And that was definitely the case with Physical Culture. You could hear Bernarr Macfadden’s voice screaming from the pages. You think people use too many exclamation points now, [chuckle] I mean, he was the king of italics, bold type, all caps. That’s what he was all about. And what he wanted to do was teach Americans, not just men, but women too, and that was another innovation of his, that if they would eat less and exercise and obsess less about Victorian morals, what he called prudery, they could have a much happier life, going forward.

Brett McKay: That idea of him making the magazine personally, he wrote about his own personal… He was sort of a proto… Like I said, he’s a proto blogger talking about him doing these things and then showcasing the results of him doing these experiments on himself like a guinea pig. And then he’d also get readers to submit stories of them following the Macfadden protocol of basically not eating very much and exercising a lot and showing pictures of the before and after.

Mark Adams: Yeah. And especially racy photographs before and after of himself. As I noted in the book, he’s the only [chuckle] politician to run for national office and circulate nude photos of himself. Because [chuckle] he’s on every page of Physical Culture. He’s showing off, here’s what happens after a week of fasting when I lift a 200-pound man off my chest. Here’s what I look like after a week of drinking nothing but raw milk. Here’s a picture of my baby doing a handstand. He really invited himself into people’s homes. And like you said, he has this proto-blogger, proto-Instagram voice that just had not been seen before in American Publishing, and caught on like wildfire.

Brett McKay: So the magazine was a huge success and a big response to it. And because of that, it laid… He started seeing the ground work for his publishing empire that he built up. And…

Mark Adams: Yup.

Brett McKay: One of the first things he did was he went to books. Like, he tried to write a book earlier, it was sort of like… He called it like a Physical Culture Love Story, didn’t get published, but he had enough capital that he could self-publish his books on the idea of health. What were some of the zany ideas he was talking about in these health books he started cranking out?

Mark Adams: I mean, once Physical Culture took off in the first decade of the 1900s, Macfadden was publishing a new book every few months to make money. He’s publishing things like The Virile Power of Supreme Manhood. He’s publishing Strengthening the Eyes, which is an eye exercise book, which a woman wrote to me when I was writing this book who said that her mother made her use it as a child and she never had to use spectacles in her entire life and she was now like 90 years old. He wrote Macfadden’s New Hair Culture, which essentially says, “If you pull at the roots of your hair, you’ll never go bald.” And his biggest book is his magnum opus is the 3000-page Encyclopedia of Physical Culture, which says it can solve any physical or mental malady, mostly through fasting and exercise. But anything you can think of from cancer to kleptomania can be solved using the Encyclopedia of Physical Culture.

Brett McKay: And as you said, this stuff was receptive at the time because Americans were really concerned about neurasthenia, getting fat, they wouldn’t be able to fight. So he had a really captive audience.

Mark Adams: Oh yeah, yeah, yeah. He’s writing books also for women. He’s writing muscular power and beauty, saying “Look, if you wanna take care of your family, if you wanna take care of the health of your husband and your children, you have to eat more vegetables, you have to eat more whole grains, you have to stop eating processed food, and you have to limit your portions.” And the thing that really stuck out to me when I started going through my notes again from this book is, everybody talks about intermittent fasting these days. That was Macfadden’s core idea. He called it the Two-Day a Meal Plan. And his description of eating a meal at 10:00 AM and then another at 6:00 PM and reducing your calories 25% or something, talk about something you could be reading on a blog today. It just it echoed so closely to the things that we’re seeing around these days. And somebody from the local NPR affiliate in New York City came out to interview me a couple of years ago, because he realized that Macfadden was also the predecessor of the keto diet. He was using this to treat kids with a… What’s the term here?

Brett McKay: Epilepsy.

Mark Adams: Yeah, yeah. Epilepsy, 100 years ago. So part of the reason why he’s so far ahead of the curve on this stuff is because he tried everything. He had these health homes, he had this utopian community that he founded. And in all of these places, he would try out these new theories and sometimes, they’d work and sometimes they didn’t.

Brett McKay: Yeah, we’re gonna talk about this utopian community he tried to establish.

Mark Adams: Yeah.

Brett McKay: But besides the extreme… Not even extreme, intermittent fasting, reducing your calories, he was the proto-paleo fitness guy. One thing he did was as a CEO of this publishing company, he lived outside of New York City but he would walk to the office… I think it was like… It was really far. But he’d walk there bare…

Mark Adams: It was 25 miles.

Brett McKay: Yeah, 25 miles every day and he’d walk there barefoot.

Mark Adams: Yeah. He would only do it one way, but it took him about six hours. And he would come up with ideas. That’s how… When he did most of his thinking, walking six hours, it was Nyack which is just over the Hudson River from New York City down to the lower end of Manhattan. And he said, “That’s when I get most of my best thinking done.” But 25 miles, it’s calorically, it’s probably like running a half marathon or something. And this is a guy who lived on a couple of thousand calories a day and never ate anything on Mondays. He always fasted on Mondays. And later in his life, when he opened a health home in Upstate New York near Rochester, which is about 350 miles, he would organize what he called Cracked Wheat Derbies, where he would get a bunch of fat people in midtown Manhattan and load up a cart with essentially wheat germ and feed them wheat germ and fresh food, and they would walk every day until they got to Rochester. It would take two or three weeks and everybody would lose 20 pounds of fat.

Brett McKay: Right, So it’s like the biggest loser, like the…

Mark Adams: Yeah, essentially.

Brett McKay: And then what’s interesting, as you’re researching, ’cause again, you were doing this because you became the fitness editor, the health editor of GQ, you actually tried to do some of these Macfadden health protocols of fasting and lots of walking. How did that work out for you?

Mark Adams: Some of them work really well. But probably the most extreme thing I tried was, I wanted to do a seven-day water fast, which was Macfadden’s big thing. And I made it about five and a half days, and I got this excruciating headache, which I now realize, was probably from not eating any salt. That’s what my doctor told me. I probably could have made it the whole week easily if I just got a little more balance in my endocrine system. But after five days I had this… I had suffered from this lingering chest infection for years and years that would come and go. And that cleared up, never came back. The other weird thing was, I’m not a particularly flexible person, but suddenly, I could lean over and touch my palms to the floor. I was incredibly flexible.

Other things I tried were two hours a day of walking, which was not only helped me lose weight, but which gave me this weird hypersensitive proprioception. I could see, feel where my body was in space to a much higher degree than I ever had before. I did a raw food diet for two weeks like Macfadden suggested. And after about a week, my sweat stopped smelling like sweat and it started to smell like cilantro or green apples to the degree that my dog started getting confused ’cause I know longer smelled like me. And at one point, I lost 20 pounds in a month putting a bunch of these things together, which I wouldn’t recommend ’cause it’s pretty extreme. But all of them had… They were mostly pros and a few cons. They were just a little bit crazy.

Brett McKay: So again, this whole thing was just eat less, move more, and that’s the advice you’d get today for losing weight. He’d just kinda go crazy with it and where it’s not healthy anymore.

Mark Adams: Right, As I usually say to people, he was two parts genius and one part crack-pot. It wasn’t enough to help somebody lose 30 or 40 pounds. He had to starve them down to their absolute bare minimum. He didn’t know when to say when, sometimes. He would cut off his children’s food if they got a cold. I met his son down in Virginia when I was writing the book. And he said, “Yeah, we would never tell our parents when we were sick because they wouldn’t say, ‘Have some soup and go to bed.’ My father would say, ‘You can’t have any more food. You can have water until you feel better. Oh, and also go jump in this cold swimming pool.'”

Brett McKay: So he had a big impact on Physical Culture. He got Americans moving, eating, doing all these fat diets, and we can still see that influence today. But you mentioned some other things that he had influence on with his magazines Physical Culture. He would basically post nearly nude photos of himself and his readers with their before and after pics. And this got him in trouble with vice squads basically. And eventually he ended up getting sued by, I think, New York government or the federal government for sending obscene things through the mail.

Mark Adams: Yes. There are two things that happened. Macfadden loved… His nickname was Body Beautiful Macfadden because he insisted that there was nothing wrong with showing off a gorgeous figure. Because of this, he started the first body building competitions for both men and women in the United States in 1903. This became what was known as the Physical Culture Exhibition. And in 1905, he put this thing on at the old Madison Square Garden, sold a few thousand tickets, it was a huge success. And there was a fellow named Anthony Comstock who was the head of the Suppression of Vice, which was an actual government job at that time. His job was to make sure morals didn’t get too out of control. And he came in and he shut the thing down. They threw Macfadden in jail, and he actually was convicted of felony eventually. So…

That wasn’t a big deal until a few years later when he started his utopian community out in the wilds of New Jersey. Decided that he was gonna move his publishing business there and mail everything out of the post office nearby. And Anthony Comstock came back again and got him on a sending indecent materials through the mail charge, and that was his second felony. He also had people running around in short shorts and G-strings, and some women were topless, helping him build this city out in New Jersey. So people coming through on the train from New York to Philadelphia would ask for the conductor to stop, so they could gawk out the windows at this craziness that was going on. The Physical Culture City was a major failure, and because he suddenly had two felonies, he was forced to go away to England, where he met the woman who led him into the next chapter of his life.

Brett McKay: Yeah, became his wife. So it’s interesting. So not only was he sort of a proponent of physical fitness, he was one of the first mainstream publishers offering sex advice at the time. This was something a lot of people didn’t even do, they didn’t talk about it. But he was sort of like a proto-Hugh Hefner.

Mark Adams: He was. His big concern was venereal disease, which was absolutely out of control in the US at that time, and not talked about. So what Macfadden said was, “Look, if we don’t deal with sex education, syphilis and gonorrhea are gonna continue to ravage the country.” It was quite normal at that time for a man to have a venereal disease and not tell his wife, so she gets it and passes along to their child when the child is born, and the cycle continues. In Physical Culture, Macfadden is hiring people like Margaret Sanger, the birth control advocate, and other sort of free thinkers of the time, and these sorts of things get him into a lot of trouble.

Brett McKay: So you mentioned, he tried to make Physical Culture City, his physical culture utopia, like most utopias, failed, and then he goes off to England and he meets who became his future wife.

Mark Adams: Well, he not only meets his future wife… Remember Macfadden is a fan of eugenics. He believes that humans can be bred like corn, as he put it in one of his books. So he goes off to England and decides he’s going to host a contest called Britain’s Most Perfect Woman. He’s 44 years old, and what he doesn’t say is that he’s essentially looking for a perfect, eugenically perfect specimen who will bear his children. So he has these women send in postcards of themselves in tight clothing, so that he can get a good look at their measurements, and he chooses a swimming champion from Yorkshire named Mary Williamson. She’s 19. They go on this barnstorming tour of England, where she jumps off of the six-foot ladder onto his rock hard abs every night, and he jumps up and yells, “Tada,” and then poses with chalk all over himself like in the act that he stole from Eugen Sandow. And somewhere along the line on this barnstorming tour, he gets her away from her chaperone and proposes to her and she says, “Yes.” And then they proceed to set off to have the perfect, eugenically perfect Physical Culture family, but not before Bernarr makes Mary sign a piece of paper saying that she will never have a doctor present at any of their children’s births.

Brett McKay: Right. See that’s what a lot of people forget, and part of American history or even history in the United Kingdom, eugenics was… That was a thing, that was a popular accepted idea in the early part of the 20th century.

Mark Adams: Woodrow Wilson was a big eugenicist.

Brett McKay: Yeah. So yeah, he gets married. Then he also, because he’s like the typical fitness writer, blogger person, he brings his family and makes it a part of his public life. He basically uses his family as an experiment to show that his ideas about fitness work.

Mark Adams: Yeah. His family essentially becomes part of the rolling Macfadden show. And Macfadden was an early adopter of new forms of media, and that was part of his greatness. First, he started putting pictures into magazines, started putting celebrity pictures into magazines, which was unknown at the time. Then when the New York Daily News came out in 1919 and took off as a huge success, he decided to publish a tabloid newspaper in New York City, which was like the hottest new thing back then. Later on, he puts his whole family on the radio. The Macfadden kids are getting up at 4 o’clock in the morning out in Nyack, and then later in Englewood, New Jersey, and taking a car into midtown Manhattan on WOR, which still broadcasts, and do calisthenics from 05:00 AM to 06:00 AM in the morning. And after that, he’s one of the first famous people in America to buy an airplane. And he zips all across America following railroad wires to navigate and crashes at least a half dozen airplanes over time.

Brett McKay: One of the interesting tidbit, and one of the part that made me laugh out loud from his family life. So all of his kids, they had a name that started with B. And I thought the funniest one… His wife wanted to name one of his daughters, Brenda. And he’s like, “No, no, no. That’s too wussy. We’re gonna call her Braunda.”

Mark Adams: Yeah.

Brett McKay: And they named her Braunda.

Mark Adams: B-R-A-W-N-D-A.

Brett McKay: Yeah, Braunda.

Mark Adams: I think they softened it with a U after that.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Mark Adams: But what had happened was, because he was so interested in breeding perfect children, his first two children were small. They were six or seven pounds. When he made the announcement in Physical Culture magazine, he added two or three pounds to make it sound more impressive. Braunda was born at 13 pounds, so you can imagine a 13-pound baby delivered with no doctor present, well, how Mary must have felt after that. He even went on to name one of his sons whom I met, Brewster because Mary wanted to name him Bruce, and he said, “No. This kid’s gonna grow up to be like a fighting cock, so let’s call him Brewster.” Now, I should say, eugenics has, to say the very least, fallen out of favor in the last hundred years. But Bruce Macfadden, when I met him, his mother was a swimming champion in England, he looked exactly like his father, except he was 6 inches taller, about 50 pounds of muscle heavier, and he went off to Yale, and as a freshman, swam on two relays and set world records. So maybe there was a little something in Macfadden’s planning, I don’t know.

Brett McKay: So he had this Physical Culture thing going on and he used that to springboard other magazines, and he basically became a publishing tycoon, like a Hearst basically. You mentioned some of the magazines, they’re basically just these confessional magazines where readers would write in these crazy stories. It was reality television essentially.

Mark Adams: Yeah. Other magazines at the time referred to it as the ‘I’m ruined, I’m ruined’ school of journalism. All he was interested in was first person allegedly factual confessional stories like, “I had a baby with my friend’s husband.” It was a formula for women’s magazines. Women’s magazines at the time were really dry, very high brow. Theodore Dreiser who wrote An American Tragedy, who wrote Sister Carrie, he was one of the editors of one of the big six women’s magazines at the time. So this confessional magazine format that Macfadden came up with was like a bolt of lightning and it took off. It sold 10 times the number of magazines that Physical Culture ever sold, and essentially created the reality first person narrative genre that we’re still dealing with today.

Brett McKay: Right. So he started True Story. And what’s crazy, this publishing empire that he began, he had a lot of influential… Or who went on to be influential media personalities on his payroll. He had Walter Winchell working for him Ed Sullivan of the Ed Sullivan Show, and even Eleanor Roosevelt.

Mark Adams: Well, what happened was Macfadden suddenly is sitting on this huge amount of money from True Story and True Detective magazine, and he decides, as many men who suddenly find themselves sitting on a pile of money do, that he wants to have greater influence in politics. And the way in the 1920s that one could have greater influence in politics was to start one’s own newspaper like William Randolph Hearst had. So he decides he’s going to do a combination of True Story and Physical Culture, put it in a pink tabloid newspaper and call it The New York Evening Graphic which has been described as the worst newspaper in American history.

So he puts together this staff with Walter Winchell, the inventor of the gossip column. Ed Sullivan is his sports writer, also acting as master of ceremonies for bodybuilding contest in evenings. One of the people who is discovered in these body-building contests was Charles Atlas. He hires the editor John Houston, the director who is fired for accusing someone of murder who was not guilty of murder, and he hires the guy who… Robert Harrison, who goes on to start Confidential Magazine, which is the most scandalous scandal rec of all time according to Tom Wolf, and which led directly to things like the National Inquirer and TMZ.

Brett McKay: Basically laid the ground work for the publishing industry, and we can see his influence today. Then in the 1930s as you talk about, you’ve already mentioned he started getting involved in politics. He reinvented himself as a politician, and of course his platform was Physical Culture. So what did the Physical Culture party platform look like?

Mark Adams: Well, Macfadden did something very clever in the 1930s. This is his third big publishing success, which was he bought a weekly magazine called Liberty, which was in the days before Time and Newsweek became huge, one of the three biggest magazines in the country. And to build circulation he allies himself with Franklin Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt. So he publishes the first big story saying Franklin Roosevelt is physically fit for the presidency and that quashes any talk that the polio had made him unable to run the country. It was a huge thing for FDR and it was a huge thing for Macfadden. It gave him a huge boost. To cement the relationship with the Roosevelts, Macfadden signs a contract with Eleanor Roosevelt saying I want you to edit a magazine about babies called Babies, Just Babies. I’ll pay you $500 a month, but if you end up in the White House I’ll pay you $1,000 a month.

So for 18 months or two years Eleanor Roosevelt is editing this baby magazine for Bernarr Macfadden. All is as this way that the Roosevelts are using Macfadden and Macfadden is using the Roosevelts. Eventually they drift apart. Macfadden is… He started off as a real progressive because of his anti-doctor stance and pro-health food and all that. But at heart he’s a Republican by the late 1930s and he really, really hates paying taxes. So around 1936, he starts spreading rumors through his publications that he would be open to accepting the Republican nomination. He gives a interview to, I think it’s the New York Herald and it’s indicative of how serious his candidacy was taken that the Herald runs a headline something like, “Bernarr Macfadden exposes himself to the Republican nomination.” At this time he’s still known for his nudism and things like that.

But he’s pushing for physical fitness. He sees World War II coming and he says, “Look, the Germans are gonna kick our ass. The Japanese are gonna kick our ass. They’re training kids in school.” And as a part of this, Macfadden develops an obsession with Benito Mussolini over in Italy, who he sees as a strong man who is training the fascists to become a master race, and he’s obsessed with this. He goes over, he meets Mussolini and because Macfadden is sort of a nervous conversationalist he blurts out, “Your fascist cadets are fat. I could whip them into shape.” And Mussolini says, “Okay. Here’s a battalion. Take them to one of your health homes.” And Macfadden invites these fascist cadets over. Puts them through their ropes for two months, cuts off their pasta, cuts off their red wine, makes them learn how to play baseball, and they each drop about 10 to 12 pounds, gain all sorts of stamina. And this is, of course, a 12-page story in Physical Culture magazine in 1931, and Mussolini orders the King of Italy to give them the Order… To give McFadden the Order of the Crown. So, he’s like a national hero in Italy. [chuckle]

Brett McKay: And so, his political career really didn’t go anywhere. He tried to move to Florida and run for the Senate, but that ended up not working out for him.

Mark Adams: So In ’36, he convinces himself he’s gonna be able to buy delegates at the Republican Convention. He doesn’t get a single delegate. He ends up sitting in his room alone, listening to the radio, waiting for his name to be called, and it’s never called. So he decides, “Okay, I’ll run for Senate in Florida,” which was a tiny population. Mississippi and Iowa had bigger populations at that time than Florida, and says, “Okay, I’m gonna run as a Democrat, even though I’m essentially a Republican, because only Democrats get elected here. And if you’re in the top two finishers, there’s a run-off and I can beat the incumbent.” So he pours all this money into an ad campaign in Florida. He gets in his airplane, he’s flying from small town to small town, he picks up momentum. When the election results start coming in, he’s number two. People are like, “Maybe he’s gonna get this run-off.” Something happens. He says that there was some skulduggery, but I couldn’t find any evidence that there was. He falls to third place. At the end of that, he goes back to New York City, and his board of directors says, “Hey buddy, you’ve been wasting hundreds of thousands, if not millions of dollars on this political career that’s going nowhere. You’re kicked out of McFadden Publications.” And as of 1941, he is no longer affiliated with the company that bears his name.

Brett McKay: And what happened in his later years of his life? How did he spend it? It sounds like America just moved on. His ideas no longer synced up with what Americans were looking for.

Mark Adams: It was. Just as I thought while re-reading this book, that I had published it at the wrong time, I probably published the book 10 years too early, it would be super timely now. McFadden was the wrong guy… Or the right guy at the wrong time. In the 1930s, by the time he had built up Physical Culture to its greatest circulation, by the time he had Liberty as a mass circulation magazine, World War II was starting. They didn’t wanna hear about his love of autocrats over in Europe. They didn’t wanna hear, as rationing started, that he thought people were eating too much and should have their meat cut off. They didn’t wanna hear, as… In the early days of antibiotics, that he didn’t believe in the germ theory of disease, and that they could just starve themselves free of pneumonia or syphilis or gonorrhea. So, what happens is McFadden fades away through the 1940s, he gets smaller and smaller, both physically and in public, becomes sort of a comic figure. He shows up the newspaper gossip column. He jumps out of an airplane on his birthday every year, but by the time he dies in 1955, he’s essentially forgotten.

In the 1950s, people like Jack LaLanne, who learned everything he originally knew from a guy named Paul Bragg, whose name you can still see on things, like Bragg aminos and Bragg apple cider vinegar at the supermarket, he was one of McFadden’s top disciples. So, secondhand, you’ve got Jack LaLanne learning from McFadden. In terms of bodybuilding, in the last few years of his life, McFadden adopts a guy named Joe Weider. Joe Weider is this Canadian strongman who starts a publishing company, starts his strength equipment company, becomes the biggest name in bodybuilding in the ’70s and ’80s. He, much like McFadden, found an immigrant bodybuilder in the 1920s, finds a guy named Arnold Schwarzenegger, and the two of them make millions and millions of dollars. People start publishing health food cookbooks in the ’60s. People start doing yoga, things that McFadden had been writing about. McFadden had written about pilates, all these things that McFadden had written about in the 1910s, ’20s and ’30s, start coming back. But because his personality is no longer there, he’s essentially buried in the mists of time.

Brett McKay: Something we’ve talked about, we can see McFadden’s influence. We’ve made that explicit, that we can even still see today on American cultures. For that, he’s someone we should remember for that, but as I was reading this book, I didn’t know what to… What was your takeaway from McFadden the man? ‘Cause as I was reading it, I found him absolutely kooky, but at the same time, I found I was actually impressed by his moxie, his confidence that he had in himself. What was your takeaway for McFadden after you finished writing a book about him?

Mark Adams: He really reminded me of some of these guys who succeed in Silicon Valley. He started with what sounded like a crazy idea, and nobody believed in him, but he just kept pushing it and pushing it and pushing it. And eventually, the world came around and the naysayers were wrong, and he was right. That said, as with a lot of things that have come out of Silicon Valley, there was a dark side to it. I mean, he had two children who died from treatments that he gave them. He had a baby boy who died because he probably had a fever and McFadden put him in a red hot sitz bath. And he had a daughter who died in her early 20s because she had a heart murmur and he made her exercise all the time and put her on a fast. So, on the one hand, he had a lot of incredible ideas. One of the last things he did before he died was he sent a letter to President Eisenhower, who had suffered a heart attack, and he said, “Here are some exercises you can do to get your heart back in shape.” Which at the time was radical, and I’m sure Eisenhower never saw the letter. But he was ahead of his time in terms of sound mind and a sound body, and he really does have that sort of personal branding, “I’m gonna drag this thing to success” sort of moxie that often equals success.

Brett McKay: Well, Mark, where can people go to learn more about the book, and this other stuff you’ve been doing?

Mark Adams: You can read about all of my books at markadamsbooks.com. So there’s a whole, whole series.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Mark Adams, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Mark Adams: Brett, it’s really been a lot of fun.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Mark Adams. He’s the author of the book, Mr. America. It’s available on amazon.com. You can also find out more information about his work at his website, markadamsbooks.com. Also check out our shownotes at aom.is/macfadden, where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM podcast, check out our website at artofmanliness.com, where you can find our podcast archives, as well as thousands of articles about physical fitness, personal finances, you name it, we got it there. And if you’d like to enjoy ad free episodes of the AOM podcast, you can do so in Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code MANLINESS at check out for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android or iOS, and you can start enjoying ad free episodes of the AOM podcast. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple Podcasts or Stitcher. Helps out a lot. If you’ve done that already, thank you, please consider sharing the show with a friend or a family member who you think would get something out of it. As always, thanks for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding all of you to listen to the AOM podcast, so put what you’ve heard into action.