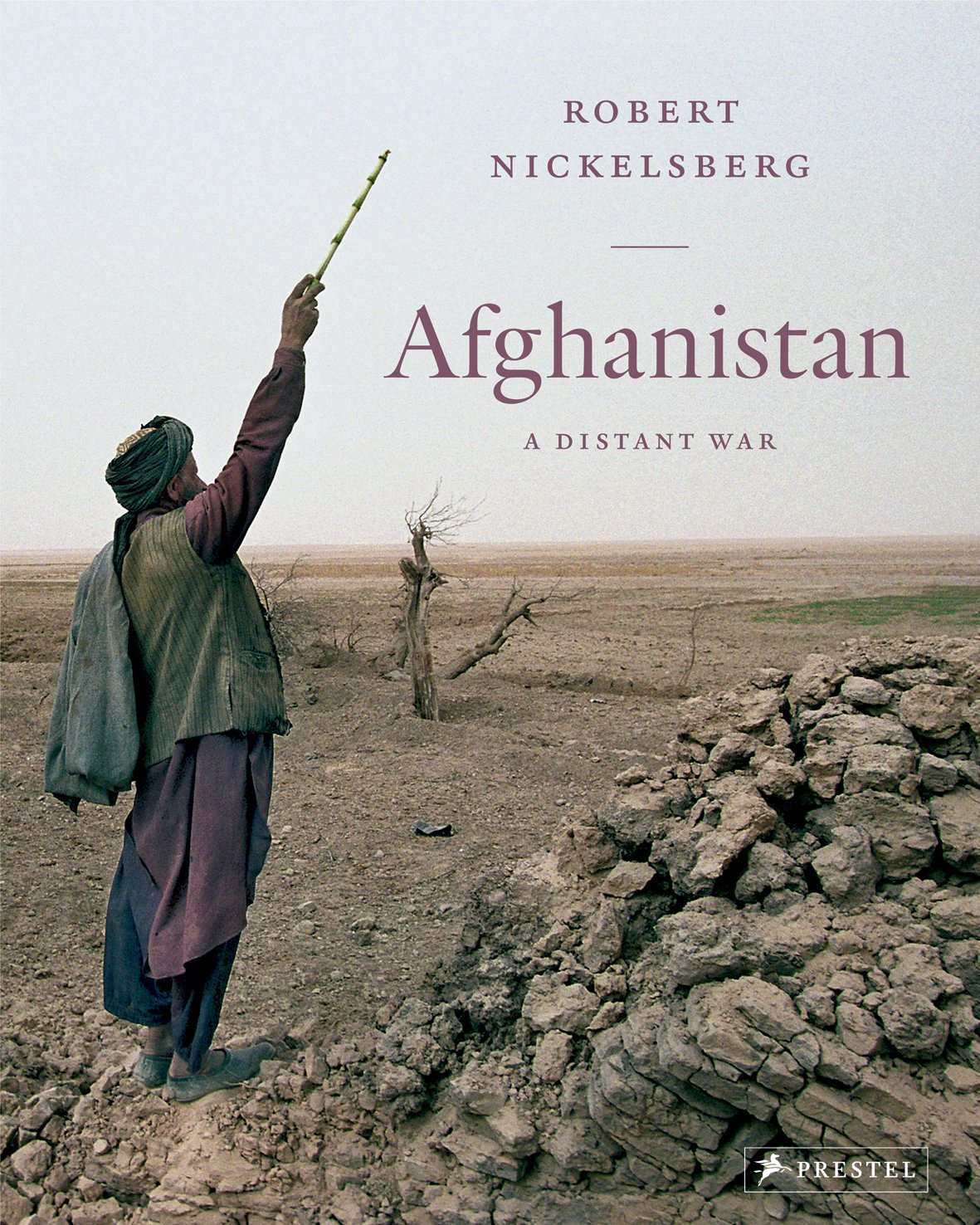

Robert Nickelsberg was a contract photographer for TIME magazine for 25 years. During that time he documented conflicts in Kashmir, Iraq, Sri Lanka, India, and Afghanistan. His most recent book Afghanistan: A Distant War highlights his work in Afghanistan from the Soviet retreat until the American conflict post 9/11.

On the podcast Robert and I discuss what it’s like working in such hostile environments, the importance of situational awareness, and what he learned about Afghan manhood. If you’ve thought about becoming a freelance photographer, you’ll get a lot of great insights from this podcast. Even if you don’t want to be a photographer, you’ll still find Robert’s career fascinating.

Robert’s book Afghanistan: A Distant War is filled with stunning photography of a place we often hear about on the news, but don’t actually know much about. Also, for more info about Robert’s work visit http://www.robertnickelsberg.com/

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here, and welcome to another edition of Art of Manliness Podcast. Today on the show we have a veteran photojournalist who has spent his career in some of the most dangerous parts of the world, capturing moments for newspapers and magazines. His name is Robert Nicklesburg, and he’s spent his career in some really crazy places. Nicaragua, during the conflict that happened there during the late 1970’s. India and Pakistan, and he’s spent a great deal of time in Afghanistan after the Soviet Union began withdrawing their troops back in the ’80s. He’s been there all the way through 2013, and seen what’s going on there with the US missions there in Afghanistan.

Anyway, stay on the show. Robert and I discuss the life of a photojournalist, and someone who strictly a photojournalist spends his time in some really scary places. We talk about how you become a photojournalist, how he got into it, if you’re interested in that. What you need to do? What drew him to that? Was it the adventure? We talk about what Afghanistan was like before 9/11. We also talk about what manliness means to Afghans, what he gleaned from that, from being so up close and personal with them. It is a really fascinating discussion. I think you’ll really like it, so let’s go on with the show.

Bob Nicklesburg welcome to the show.

Bob Nicklesburg: Thank you Brett. Very nice to be here.

Brett McKay: You are a veteran photojournalist. You spent a great deal of your career in Afghanistan. How did you become a photojournalist, and how did you end up in Afghanistan of all places?

Bob Nicklesburg: I became a photojournalist in the late ’70s as a freelance, starting out in New York City. Learning the ropes, starting from the ground up, struggling to sell individual prints, individual pictures. I spent some time in Washington on Capitol Hill learning how that process functions for the media. It’s very disciplined and quite different than the rough and tumble street side of being a photojournalist. Then I ended up in Central America in 1979. I had an interest in Nicaragua, and particularly the Sandinistas and the conflict brewing there with General Somoza, who was a strong U.S. ally. I became interested, I’ve always been interested in current events, and enjoyed traveling, and photography certainly fit the bill.

Brett McKay: It seems like you’ve been drawn to places where there’s conflict. Was it just the sense of adventure, some of the great writers like Jack London, Ernest Hemingway, they started their careers as reporters, or they spent of their career’s as reporters in the front lines of conflict; so they were just there for the adventure. Was that you, or were you just generally interested in what was going on here?

Bob Nicklesburg: No, the sense of adventure needs to be in any profession really, to do it effectively. I enjoyed recording the historical moment. The more time I spent at it, the closer I could get to it. You could almost put your arms around it and then see it published the next day. I did have some idea of, “There’s a result from all this effort,” whether it’s a day’s assigned or a two week project. As far as Afghanistan goes I moved to India for Time magazine in 1987, ’88, coming from Southeast Asia, and knew that this was a very historical moment in context of the Cold War, the end of the Cold War.

The Soviet Army was in place in Afghanistan. A lot of Arab Jihadis were also filtering through there, and there was also the beginning of the Kashmir Conflict inside India, also dependant on the Pakistani political situation; martial law in Pakistan and Bangladesh; a civil war in Sri Lanka. South Asia was very busy, and it was not on the radar screen the way it is today. Thankfully Time Magazine had an Asian edition out of Hong Kong, which we could publish regularly. Aside from the Cold War issues with Gorbachev and Reagan, it was very difficult to get the Afghan conflict into publication in the U.S. I was able to follow it all the way through and my last trip there was in 2013. I lived in India for 12 years.

Brett McKay: Wow. What was your first trip like to Afghanistan? You were there the Russians, or the Soviet Union started withdrawing, correct?

Bob Nicklesburg: Yes, prior to that in 1987 there were no visas during given the Russian Army occupation in Kabul, very few. Also, if you did get to Kabul you were very closely monitored. In 1988, my first trip was in January across the border from Pakistan into Afghanistan for a funeral. There was still the Mujahideen were fighting the Russians and the Afghan Army, but there was truce for the burial of a very well known Afghan politician from during the British Empire days prior to 1947. There was a funeral in the Eastern city of Jalalabad, in January of 1988; that was my first trip across with a visa in my passport.

Prior to that you had to go in across the border I guess you could say illegally, but go in with Mujahideen and you would be off for a week, two weeks, a month, whatever. Very haphazard, but in this case I realized that the story was going to change once the Soviet Army had announced that they were going to withdraw. They were going to do that in public and they allowed journalists to come in in May of 1988 to cover that withdrawal.

The first trip that I had in January of 1988 at this funeral in Jalalabad; halfway through the funeral ceremony there were two very, very loud explosions in the parking lot off in the field, about a quarter mile away. Obviously it was a set explosion, and it created complete panic and pandemonium. Close to twenty people were killed. Everyone lost their driver; you couldn’t figure out how to get home back across into Pakistan. My first trip in was face to face with a violent situation, yet you had to maintain some composure and record it.

Then, three months later, I applied for another visa and got into Kabul for the first time in March, April, May, those three months, we were able to get a number of visas to go in and spend time there.

Brett McKay: When you were there in the beginning, what was it like to be a photographer? Because if I remember correctly, there were rules, particularly with the Taliban, about no photography … you can’t take pictures of people, or something like that. You take pictures of stuff. Was that …

Bob Nicklesburg: The Taliban came out of the Mujahideen, which came out of the Afghan Army, the Communist Party of Afghanistan, which came out of the Soviet occupation. Pictures were not prohibited in those years from 1988 to 1996, when the Taliban came in. In fact, taking pictures of women is frowned upon and that was true in those years prior to the Taliban, but generally, Afghans like to have their pictures taken. The Taliban initiated these very strict guidelines in 1996. Yet, off the side, Taliban would like to have their pictures taken as soon as their leader or their officer would go off. You’d hear a whisper, “Please, take my picture.”

There was a bit of hypocrisy there, but if you were careful and tried to be as unassuming as possible you could work. Not in all situations under the Taliban, but generally the Afghans are not camera-shy.

Brett McKay: Why did they want their picture taken? Did you show them the pictures? This wasn’t the time of digital cameras, where you could show them right away.

Bob Nicklesburg: Right. No, they were very unfamiliar with outside media. They had one government radio station, one government television station, one newspaper. When you have barely 30% literacy in that country, and it’s 80% agricultural, wherever you go there’s really no concept of publishing; or, having your picture seen is often done from a marriage, from a special situation; an anniversary of some sort; a graduation; maybe Afghans had their pictures taken then. There were no photo labs, or very few wedding photographers, for instance. They enjoy having an image of themselves. This sort of confirms their identity, if you will. I never found it completely impossible not to work there.

It became very awkward at times. The reporter could interview but I couldn’t photograph in many situations. It became a challenge to go out into the general public and to try to work that way rather than photograph a leader during an interview, for instance; but the reporter could record them and take notes, yet I couldn’t function in a lot of … in official capacity. The Minister of Justice, who was a very strange fellow under the Taliban, would not allow photographs, yet he spoke clearly into a microphone. You just have to accept those ground rules.

Brett McKay: Yeah. How did things change after 9/11 and the occupation of … the beginning of ground forces, US ground forces in Afghanistan? What was the change like, from before and after?

Bob Nicklesburg: Quite extreme, actually. The Afghans were very happy to be unshackled and to be much freer with their daily lives. They knew that under the Taliban regime it was an unnatural situation, and they put up with it. The Afghans are survivors in every sense of the word. They love dance, and they don’t like to be bossed around. Those were many restrictions that they had to live with under the Taliban; those were gone. Generally, Afghans like Americans. They find them happy, easy to talk to, and easy to steal from because Afghans are very clever and they’re constantly looking for ways to take advantage of you, often in a humorous way, but then also in a very direct way if you cross the line and don’t understand their culture or their traditions and …

Brett McKay: Did that ever happen to you?

Bob Nicklesburg: Did that ever happen to me?

Brett McKay: Yeah, have some thing stolen from you.

Bob Nicklesburg: I did. I had some cameras stolen at a press conference in 1997 at a base of an Afghan military commander when the Taliban were coming up close to Mazar-i-Sharif up in the northwest. I’d left some cameras behind in the room, went out to get some fresh air, and came back and the cameras were gone. I created a … and this was in a compound. They found the people who served tea during the press conference and roughed them up, and eventually I got the cameras back. You had to be careful. Don’t give people the opportunity to steal. It is a great crime, particularly with … Muslims generally don’t steal from each other and the penalties can be severe. The Taliban would cut off a hand. Corporal punishment. Other than that, you just had to expect someone to try to see if they could get something from you, whether you weren’t looking, or get into your bag, or … It’s par for the course, but not just Afghanistan, remember. I worked in South Asia.

Brett McKay: That’s true.

Bob Nicklesburg: All countries have a similar culture that way, and you have to tip people, and if you don’t, they’ll try to come back at you the other way. They expect foreigners to give them a tip. There are certain customs and traditions that, if you’re willing to take the time, be a good observer, you’ll see how the local people function. They’re of course robbed, but it’s due to ignorance, really.

Brett McKay: Yeah. What’s the … I’m always curious about this … What is the status of a journalist like yourself in a conflict zone? How do the American troops see you? How do the locals see you? Because sometimes it seems like you’re sort of in a no-man’s land at times, if you get really in the thick of things.

Bob Nicklesburg: Well, you do have to figure, where are you the most secure in a chaotic situation. You don’t always obtain an answer or find a solution to that. That may be what you’re referring to, this “no-man’s land,” but you certainly want to be around the commanding officer, or someone who’s giving the orders, to find out what they’re trying to do or what the plan is. Then you can go off and see how it’s carried out.

You do need to introduce yourself with the Americans … I’ve been working with the American military since the early 1980s in central America. For me, embeds were never an issue. I knew how to work with the military; it didn’t restrict me. The way I looked at it, it provided me with transportation and security to areas I wouldn’t be able to get to as a civilian. It does limit you, in that you’re not able to talk to the opposition, for instance, whoever those people are. The idea was to see what the Americans, and their big military footprint, what they were doing. I would try to maximize my time with them, whether it was a week, a day, a month, living on a base looking for opportunities to get out on a helicopter, photographing daily life of the soldier. Whatever it took, to spend time with one side or the other. During the Mujahadeen days, in the civil war, in downtown Kabul for instance, you needed to know how to get in and out of different neighborhoods, where the front line was, where to be before sunset so you could get out of that area, and how good your driver was. Find out who the neighborhood leader was.

You had to do a lot of homework, and that would help with the limited amount of time you had in the conflict zone. You have to figure you might be out of there in twenty minutes. You have to start working immediately and then ask for permission in some cases, rather than ask for permission first. You had to be able to juggle that kind of a situation as quickly as possible, and either go formal, or go informal. Find out where the communications center would be, for instance. Find out where that clinic is. If you can’t work at the front line, you can work at the clinic where the wounded come back to. You could do both, ideally, but you had to plan very carefully how you would spend your time.

Brett McKay: You and I have exchanged some emails about situational awareness. Was that something you had to develop, as … I don’t know … Did you realize you’d have to learn how to become situationally aware before you went into these places, or was that something you just sort of developed naturally as a matter of being in these environments that were always rapidly changing? How did you go about developing that?

Bob Nicklesburg: I think in a lot of third-world countries, developing countries, where I lived … Remember, I didn’t parachute into places and go back to first-world countries. I stayed four years in El Salvador. You get to know the rhythm of a place as best as you possibly can, what to expect; which is often to expect the unexpected, the spontaneous. Remember where your car is. Don’t park your car face-in; park your car with the rear so you can get out of there fast, or if you hire a driver make sure the driver doesn’t spend his time in a restaurant when you most need him to get going, for instance. Yes, situational awareness: you either have it or you don’t. You can get rusty, certainly, if you’re all of the sudden covering the flower show for six months and then you drop yourself into a conflict zone, you’re going to see that you are a little slow, getting out of the gate. Yes, one of the beauties and one of the main elements that attracts me to developing countries is how spontaneous they are. It’s the unpredictable. It’s also the ambiguous, the gray area, the shade, what’s going on out there; nothing is as clear as we like it here in the United States. Yes or no. It’s in the “maybe” zone that you’re going to find an answer to really what’s happening.

Brett McKay: How long have you been back in the states, for a continued [crosstalk 00:23:25]?

Bob Nicklesburg: I moved back to the United States in 1999, 2000, but I continued to go overseas, and I continued to go to Afghanistan and India throughout that period when I was here. The last trip to Afghanistan was in May of 2013, for the last pictures of the book.

Brett McKay: Mm-hmm (affirmative). What have you done since then?

Bob Nicklesburg: Since moving back to the states … Having lived close to twenty-five years outside of the US, I’m relatively new to my home country and getting to know it again … I’ve worked a lot around the 9/11 issue, once that happened, certainly with the Homeland Security department, and counterterrorism, all the way down to street gangs in Los Angeles with the Los Angeles Police Department, Mara Salvatrucha, MS-13, street gangs from Central America that are very violent here, I’ve found to be a legacy of the time that I spent in Central America. Actually, many people who came north as immigrants got pulled into these street gangs after I left El Salvador, so it was a way for me to tie those environments together.

Particularly now, I’ve worked quite a bit on human trafficking, as well as Muslims in America, post 9/11; how they handle being targeted or how they integrate themselves in daily life in the US. Very much issue-oriented.

Brett McKay: I see. I’m curious about this, and it’s okay if you don’t have a full answer for it. You had a chance to be helping up close and personal with Afghans. I’m curious if you observed anything about their notions of masculinity that are different from, say, in the United States. Was it different from tribe to tribe, or was there sort of an underlying ethos amongst all of them?

Bob Nicklesburg: There was a great amount of pride in either the tribe or the individual. There’s still, from the rural areas to the urban areas, you will see a difference, obviously, but they’re very independent people. There’s certain sensitive areas that, as Westerners, you don’t talk about, particularly about their family or about the women in their family, for instance; you have to be very, very careful about that.

Also, I noticed things start off very formally and within an hour you’ve made a friend for a very long time. They’re looking for ways to see if you can be trusted. Remember, contracts are not signed there; it’s done on a handshake. Trust, faith, confidence, really has to be built up over a period of time, whether you have a half an hour with somebody or three, four, five years as a neighbor. They want to feel confident about you, and they certainly do exert their masculinity over members in their family. Elders must be listened to, particularly the men. Women are very often kept down in the sense the way we look at gender equality in this country and in Europe, for instance. Women are, in a not-so-subtle way, looked at as property. It’s not that difficult for a male to exert his authority over his family, and particularly women.

It’s a complicated issue in that country, gender equality, and not easily addressed in the countryside as much as it might be evident in urban, city environment. That’s also true in India and Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, all the countries that I worked in recently.

Brett McKay: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Bob Nicklesburg: As well as the Middle East. It comes through in different ways. You can know somebody in Afghanistan for ten years yet never meet their wife, in a very traditional family; or, the daughters will come out and then eventually you might get to meet the spouse. There might be more than one, and you have to figure out whether or not you can reach out and shake their hand the way we so … Our first reaction is to shake people’s hand. There, you wait to see if the woman will put their hand out, and the males are watching this very closely. You have to respect that. I think there might be subtle indications that there’s a masculinity difference between the cultures and then some not-so-subtle; the way you cannot intervene if a woman is being abused or pushed around by a male. You pretty much have to go across the street and and not bother, whereas that kind of chivalry would be expected here.

It’s slightly complicated, but it’s a very good question, and point that you raise.

Brett McKay: I’m sure there’s some folks who are listening to this, a lot of younger guys who want to become a photojournalist. For those guys, what’s your advice for them? If that’s what they want their career to be, what’s the best way to get started?

Bob Nicklesburg: The best way is to perfect storytelling, whether it’s through sound, video, or still photography. We’re all storytellers, and you can perfect it, but whether or not that can be learned from zero to a hundred, that’s one issue that you have to decide whether you’re able to tell a story with pictures; and how closely you want to work with individuals, or do you work better in a studio with objects that don’t talk back to you, or architectural photography, for instance.

I also think you need to read. Do your homework; become as well informed an issue that you possibly can and then go out and try to work from dawn until dusk. Work with light, work with the elements, understand the machinery that you have. Cameras are just machines; it’s the person behind it that really has to figure out aesthetics, sequencing, chronology, editing, and all that comes out in the wash as a story and how you present that to editors. It’s a 360 degree approach. That’s not as easy as people think it is. You may have good impulses, good instincts, but you have to get that under control and have strict discipline and a work ethic.

Brett McKay: Can you have a family with this job, because it seems like you travel a lot?

Bob Nicklesburg: Journalism, photography is not great for domestic tranquility, I guess you could say. I don’t have children. I’ve pretty much led the life of a gypsy until I was married in 2000, but no children. Yes, it presents a lot of stress and you better have the right partner. That’s all I can add to that, really respect other people. I don’t go to work knowing I’m going to come home at five; that’s pretty obvious. Nor do other successful photojournalists or videographers or reporters, for that matter. It’s just not possible.

I’m not often around for anniversaries, or Thanksgiving or Christmas. If that can be established, a relationship will be able to be maintained.

Brett McKay: You got to be up front with a potential partner, that …

Bob Nicklesburg: It’s no secret that I have a bag packed pretty much all the time, or at least I know how to do it with one eye closed, yes.

Brett McKay: Well, Bob, where can people learn more about your work?

Bob Nicklesburg: I would think the best place, particularly with the Afghanistan work, is the book that’s recently come out, “Afghanistan: A Distant War,” which is available online, of course, or in bookstores; and on my website, robertnicklesburg.com. You can see a lot of the work that I’ve done over the years.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Well, Bob, this has been a fascinating conversation. Thank you so much for your time.

Bob Nicklesburg: Thank you, Brett; enjoyed it.

Brett McKay: Our guest today was Robert Nicklesburg. He is a photojournalist, and he’s just recently come out with a book called, “Afghanistan: A Distant War.” It’s a collection of just really arresting, beautiful pictures throughout his career in Afghanistan, starting in the ’80s with the withdrawal of Soviet troops. Really, just beautiful photography. Go check it out. You can find that on amazon.com, and like Robert said, you can find out more about his work at robertnicklesburg.com.

Well, that wraps up another edition of The Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out The Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoy the podcasts I’d really appreciate if you would go to Stitcher, or iTunes, or whatever it is you use to listen to podcasts, and give us a rating. Doesn’t matter what it is, I don’t care. Just give us a rating; that will help us out, and give us some feedback. Also, let your friends know. We appreciate that as well. Until next time, this is Brett McKay, telling you to stay manly.