Both soldiers and civilians alike have always taken an interest in the tests the Army uses to assess physical fitness and readiness for combat.

For soldiers, the reason for their interest is obvious — how they do on the test is linked to job performance, retention, and advancement.

Civilians are interested because they’re curious about the standards those who protect their country are required to meet, and wonder how’d they do in measuring up to those standards themselves.

Each of the various iterations that the Army’s physical training test has gone through since it was first introduced almost 75 years ago offers an interesting snapshot and reflection of the country’s general culture at the time. The standards of the test have evolved, along with changes in gender inclusion, scientific knowledge of health and exercise, and the shifting demands of various wars.

The test’s standards have generally toughened during times of war, and softened during times of peace, and the difference between these poles has roughly translated into the difference between a focus on combat readiness, and a focus on general fitness.

The current Army Physical Fitness Test centers on the latter, but that hasn’t always been the case. Today we’ll trace how the modern PT (Physical Training) test came to be, what came before, and where the test may be going. It’s a subject worth learning about for soldiers and civilians alike, not only because it’s pretty fascinating, but also for its wider implications; it’s quite an instructive case study in understanding the human cycle of laxity and vigilance.

Ready for Battle: The Physical Combat Proficiency Test

“Over a period of years and the course of several wars, the costly lessons learned from our past military experiences led to an increasing interest in the physical condition of the fighting man. With this interest has come the ever increasing realization that our troops must be well conditioned to operate effectively. No longer can we afford emphasis on physical fitness during wartime and de-emphasis during peacetime. It is evident that, in spite of increased mechanization and modern weapons, physical readiness retains a vital place in the life of each individual solider and in every unit within the Army.†—FM 21-20, Physical Readiness Training (1969)

Historians of military fitness have long observed that an emphasis on physical training waxes during wartime, and wanes during peacetime — both in the armed services and in the population at large. Civilians and soldiers simply aren’t as motivated to stay strong and fit when there isn’t an immediate threat to deal with nor a strong likelihood of being called to serve in combat. As a result, when a draft is instituted, a large portion of eligible men are found unfit for service, and the military initially struggles to adequately train their troops and bring them up to speed.

As the war progresses, the impact of soldiers’ physical inadequacy on casualties and success is clearly realized and real-time lessons from the battlefield emerge as to the kind of physical training and skills that are needed to address these deficiencies. These insights make their way into the military’s official PT programs in the later stages of the war, and are codified in manuals in the years following the conflict’s conclusion…only to be relaxed and modified once more as troops settle into a peacetime routine and no imminent crisis seems to loom.

When WWII broke out, for example, half of the first two million men called up by the Selective Service were found unfit for duty, and 90% of these rejections were due to deficiencies in health and fitness. For this reason, the military started scientifically researching the best ways to exercise its men and prepare them for combat. The result was the introduction of a robust physical training program, as well as the Army’s first physical fitness test. The test consisted of a 5-event battery of events: squat jumps, sit-ups, pull-ups, push-ups, and a 300-yard run (you can take the test yourself here), and was designed to test the kind of muscular endurance and anaerobic capacity soldiers would require on the battlefield. The physical training program and test were developed during the war, and then codified in a PT manual in 1946.

Yet in the years following WWII, physical training standards once again grew lax. As many military strategists felt that the advent of nuclear weapons had made ground warfare largely obsolete, an emphasis on physical readiness waned and soldiers were allowed to grow softer. Consequently, American troops struggled in the Korean War, and military analysts traced many of the conflicts’ causalities to a lack of physical hardihood and preparation for the rigors of battle.

And so the oscillating pendulum of physical readiness swung back again; by the end of the 1950s, the Army took the lessons it had learned in Korea and began to draw up new standards for soldiers’ physical fitness — ones aimed specifically at enhancing their focus on combat readiness. The necessity of these efforts was made clear as combat operations in Vietnam got underway in the 60s; the military got real-time data back from the field as to how soldiers needed to be trained in order to withstand the kind of guerilla warfare being waged in the jungles of Southeast Asia.

The result of this effort was a new program of physical training and testing that was first introduced in 1959, and revised and codified a decade later in FM 21-20, Physical Readiness Training — the Army’s PRT field manual. As the name implies, the new program was aimed at developing soldiers’ “physical readiness,†defined as a “combination of training to develop proficiency in physical skills and conditioning to improve strength and endurance.†The training emphasized exercises that developed strength, muscular endurance, anaerobic and aerobic capacity, agility, and coordination, as well as the attainment of “proficiency in certain military physical skills which are essential to personal safety and effective combat performance:

- Running — Distance and sprint running on road and cross country.

- Jumping — Broad jumping and vertical jumping downward from a height.

- Dodging — Change of body direction rapidly while running.

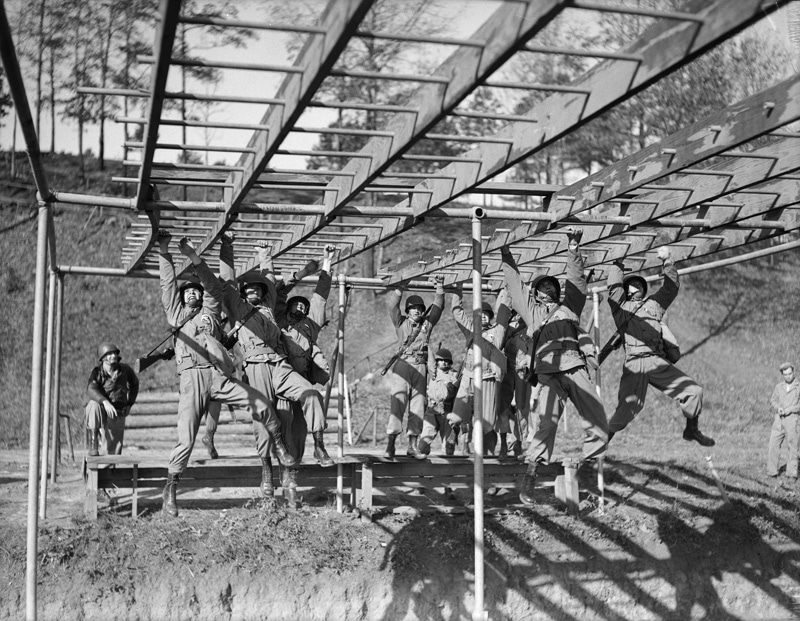

- Climbing and traversing — Vertical climbing of rope, poles, walls, and cargo nets. Traversing horizontal objects such as ropes, pipes, and ladders.

- Crawling — High crawl and low crawl for speed and stealth.

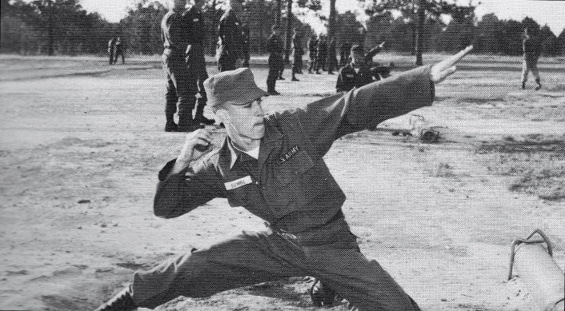

- Throwing — Propelling objects such as grenades for distance and accuracy.

- Vaulting — Surmounting low objects such as fences and barriers by use of hand assists.

- Carrying — Carrying objects and employment of man carries.

- Balancing — Maintaining proper body balance on narrow walkways and at heights above normal.

- Falling — Contact with the ground from standing, running, and jumping postures.

- Swimming (in specialized situations) — Employment of water survival techniques.â€

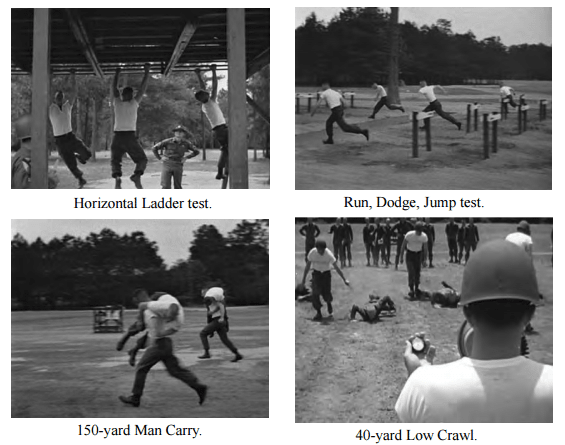

To gauge whether a soldier had gained the required aptitude in these physical skills, and was prepared for the demands of battle, the Physical Combat Proficiency Test (PCPT) was created. It consisted of five events: low crawl (40 yards), horizontal ladder/monkey bars (20 feet long), grenade throw (sometimes substituted for a 150-yard man carry during basic training and for combat-support troops), ‘dodge, run, and jump’ (agility run), and a 1-mile run. While completing the test, soldiers were required to wear their combat uniform (sans jacket) and boots.

All male soldiers were required to take the PCPT to graduate basic training, and periodically throughout their enlistment. Women, who were then part of the separate Women’s Army Corps, took a much lighter and less strenuous test, which consisted of arm circles, body twists, a bent-over “airplane†exercise, sit-ups, and jumping jacks.

From Readiness to Fitness: What Happened to the PCPT?

The Physical Combat Proficiency Test was arguably the Army’s high-water mark for the testing of functional fitness. But even though the PCPT was a rigorous test that closely linked its standards with the standards of “job performance†in combat, it didn’t last.

Within just a decade, several factors originating from the civilian world would combine to create a very different test.

First, in 1975 President Gerald Ford signed a bill allowing women to enroll in the nation’s service academies for the first time. As performance on the PCPT was a part of graduation requirements, as well as Officer Evaluations Reports, some officials worried that women would struggle with the test’s standards, especially when it came to the horizontal ladder, and that their low scores would hold them back from advancing to leadership positions.

Then in 1978, the Women’s Army Corps was disbanded, and female soldiers were integrated into non-combat male units. In conjunction with this change, the Army wished to create a sex-integrated fitness test that could be taken by all of its troops.

There were other changes to the make-up of the Army as well. After Vietnam, the military once again became an all-volunteer force, and some of the new recruits were not as fit as the exiting veterans. Obesity began to be a problem in society as whole, and in the military as well, spurring the Army to become increasing concerned about keeping down the weight of its soldiers.

At the same time, an emphasis on cardio-respiratory endurance was coming to dominate the health and fitness discussion in the civilian world. Slow, long distance running/jogging was rising to prominence, and the military began to see aerobic health as the most important determiner of overall military fitness (as well as a way for potentially obese soldiers to keep off the pounds).

As the Cold War continued, there also remained those who felt, the wars in Korea and Vietnam not withstanding, that ground combat was a thing of the past, and that as warfare became more and more mechanized, combat would become less and less strenuous; thus, while it was desirable for soldiers to maintain a general level of health, a high level of fitness and combat readiness would be unnecessary.

In addition to these factors, the Army was keen to come up with a PT test that, unlike the PCPT, didn’t require any equipment and thus could be done cheaply and in any conditions.

So it was in 1980, that the Army introduced a new fitness test for its soldiers: one that was deemed more equitable for women, included gender normed standards, focused on general fitness, health, and weight control, and required no equipment. The PCPT’s five, combat-related events became three: 2 minutes of sit-ups (rest/pauses allowed), 2 minutes of push-ups (ditto), and a 2-mile run.

The test was at first called the Army Physical Readiness Test, but in 1985 the name was changed to the Army Physical Fitness Test (APFT) to better reflect its new emphasis, as well as a change made that year in what a solider was allowed to wear for the test; whereas they had formerly had to complete the test in their combat uniform and boots, now they could take the test in their PT uniform (shorts/t-shirts) and sneakers.

Overall, the new APFT was more accessible and less rigorous; rather than centering on assessing a soldier’s readiness for combat, as the PCPT had done, it aimed to gauge whether or not he or she was living a generally healthy lifestyle.

From a Focus on Fitness to a Flirtation With Readiness, and Back to Fitness Again: The Aborted Army Physical/Combat Readiness Tests

While the Army’s physical training test was changed in the 80s, the physical training program remained largely the same, and still retained an emphasis on combat readiness — at least on paper (how PT is carried out on the ground depends on the preferences of whoever is leading it). The Army encouraged its troops to see the APFT as only a snapshot of their health — a check of their minimum baseline of fitness — and not to build their physical training regimens around it.

But, because scores on the test are kept as part of officers’ official files and repeated failures can result in a soldier being separated from the service, in practice, PT invariably began to focus more and more on preparing soldiers to pass the APFT’s 3 events. The result was widespread “teaching for the test,†so to speak. Or as is often said in leadership circles, “you get what you measure.â€

This wouldn’t be a problem if the APFT was widely believed to accurately measure soldiers’ overall fitness and readiness for combat. But it has instead found much criticism on these points from the very beginning.

Critics of the APFT feel it is too easy, provides too narrow a snapshot of a soldier’s all-around fitness, and has little connection to the physical tasks actually required in combat. For starters, the test emphasizes low intensity, cardio-respiratory exercise, whereas combat is most likely to tax a soldier’s anaerobic rather than aerobic capacity; in battle, soldiers are far more likely to have to sprint, than to have to run for 2 miles non-stop.

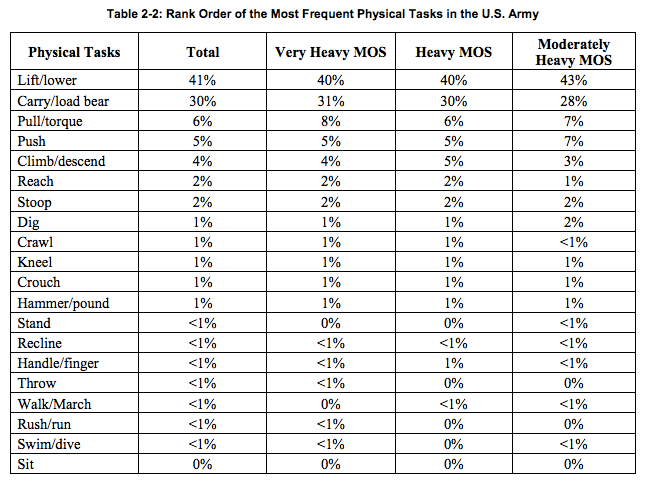

Then there’s the limited range of physical skills and capabilities tested by the APFT’s 3 events: sit-ups are widely considered an outdated exercise altogether, and there is no assessment of a soldier’s ability to lift, carry, pull, and climb, even though studies have shown that these are the most common physical tasks required of soldiers:

MOS=Military Occupational Specialities=Army jobs. Chart Source.

As Gen. Mark P. Hertling, of the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) put it:

“Today’s PT test does not adequately measure components of strength, endurance, or mobility. The events have a low correlation to the performance of warrior tasks and battle drills [known as WTBD; the critical physical skills needed to survive in combat] and are not strong predictors of successful physical performance on the battlefield or in full spectrum operations.”

All of which is to say, that many military fitness experts feel the APFT only gauges physical health in a very narrow way, and fails to gauge physical skill; it’s a general fitness test, rather than a combat fitness test, but doesn’t even serve that first purpose well.

Concerns over the weaknesses of the APFT were easier to overlook during peacetime, when the combat readiness of troops could be viewed more abstractly, and didn’t have life or death consequences. But during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the cycle of laxity/focus on the importance of physical training turned round once again.

Many lessons were learned from soldiers’ deployments and battles in the Middle East, while in the civilian world, exercise trends and sport research were pointing away from endurance cardio and towards the value of high intensity exercise and CrossFit-style “functional†fitness workouts.

Thus in 2010 TRADOC released Training Circular 3-22.20, which provided a new emphasis on incorporating warrior tasks and battle drills into physical training. (The circular was then codified in the PT manual in 2012.) The Army began to talk of turning their troops into “soldier athletes†or “tactical athletes†who had the strength, endurance, agility, and coordination to fight and win on the battlefield.

Then in 2011, TRADOC announced that the Army would be replacing the APFT with not one but two tests that were meant to better correlate with the new priorities of the physical training program.

Once again a new focus was reflected in the suggested name change; the Army Physical Fitness Test was to be replaced with the Army Physical Readiness Test. Sit-ups were dropped, push-ups were sped up, the run was shortened by a half mile, sprints were added, and the 3-event battery was increased to 5:

- 60-Yard Progressive Shuttle Run (5-yd, 10-yd, and 15-yd round trips = 60 yds)

- One-Minute Rower (rather than done on a rowing machine, this was to be a core-testing exercise performed on the ground and done non-stop)

- Standing Long-Jump

- One-Minute Push-up (done non-stop without rest)

- 5-Mile Run

Overall, the APRT was designed to up the intensity factor of the test, and assess both aerobic and anaerobic capacity.

A demonstration of the hurdle and casualty drag components of the eventually aborted Army Combat Readiness Test. (Image Source)

TRADOC also recommended that soldiers undergo a second test: the Army Combat Readiness Test. The ACRT was designed to gauge a soldier’s ability to perform the warrior tasks and battle drills mentioned by Gen. Hertling above — the physical skills they’d need on the battlefield. The test was to consist of 7 events and had to be completed while wearing one’s combat uniform and helmet and carrying one’s weapon:

- 400-meter run

- Obstacle course with low and high hurdles and crawling obstacles

- 40-yard casualty drag

- 40-yard run with ammo cans on a balance beam

- Sight picture drills with your weapon while moving through obstacles

- 100-yard ammo can shuttle sprint

- 100-yard agility sprint

Together the tests were designed to create closer alignment between soldiers’ physical readiness training and the physical requirements they were tested on; PRT would drive the test, rather than the other way around. And most importantly, it was hoped the test would provide an accurate assessment of whether or not a solider was ready for the rigors of combat.

The implementation of the APRT and ACRT was described by TRADOC as “the final step in the Soldier Athlete initiative to better prepare Soldiers for strenuous training and the challenges of full-spectrum operations.†All that remained to be done was for different channels of the Army to review the requirements and for the test to be administered to thousands of troops in order to establish baseline standards.

Yet, just a year after they were announced, the new tests were scrapped, or rather put on indefinite hold, pending further research. The reasons for the reversal were never made entirely clear. The cost of the equipment required, that the events weren’t proven to be linked to combat job performance, or that some commanders were simply resistant to the idea, were all cited as rationales for the change of course.

And so the Physical Fitness Test of sit-ups, push-ups, and running continues to remain in place. With combat positions opening to women, there’s been talk of the introduction of a new kind of functional, job-specific, gender-neutral test, in which recruits must qualify to be eligible to serve in certain positions. It’s still in the works.

Conclusion

“Few recruits are physically fit for the arduous duties ahead of them. The softening influences of our mechanized civilization add difficulties to the problem of conditioning men and thereby make physical fitness more important than ever before. Even within TOE [support staff/non-frontline units], labor saving devices and mechanized equipment exert this softening effect. If men are to be developed and maintained at the desired standard of physical fitness, a well-conceived plan of physical readiness training must be part of every training program.†—FM 21-20, Physical Readiness Training (1969)

Throughout the seven-decade history of the Army’s PT test, the rigor of its standards, and whether it emphasized combat readiness or general fitness, has fluctuated along with the cycle of peace and war.

In peacetime, when the prospect of serving in combat seems remote, physical training relaxes and soldiers grow softer, content to maintain the minimum baseline of fitness required by a milder PT test.

In wartime, the vital importance of physical readiness is once again made patent and proven in the field, and these lessons lead to the toughening of PT training and tests.

The lesson in all this for both soldiers and civilians is clear: complacency kills.

Ground warfare is obsolete…until it isn’t. Mechanization is going to make battle a cakewalk…and yet the need to carry 60-100 pounds of gear while dragging a 200-lb comrade stubbornly sticks around. Everyone is sure a big crisis requiring the reinstitution of the draft will never, ever happen…right before it does.

The takeaway of course for all individuals is never to allow things like institutional bureaucracy or gender politics or cultural fads to set your personal standards for physical prowess. To always exceed the minimum. To remember that what you measure is what you get, and to set goals accordingly. And to strive to be not just healthy, but skilled — not fit for life, but ever ready for action.

_______________

Sources:

A Historical Review and Analysis of Army Physical Readiness Training and Assessment by Whitfield B. East

Too Fat to Fight, Too Weak to Win, Soldier Fitness in the Future? by Maj. Mark R. Forman