When people talk about military special forces, the Navy SEALs are often the first to come to mind. But there are several special forces in the military that have a storied history and play a fundamental role in America’s military defense. My guest today is the only person to have been allowed to audit and write about the training programs of the respective special forces units of every branch of the military.

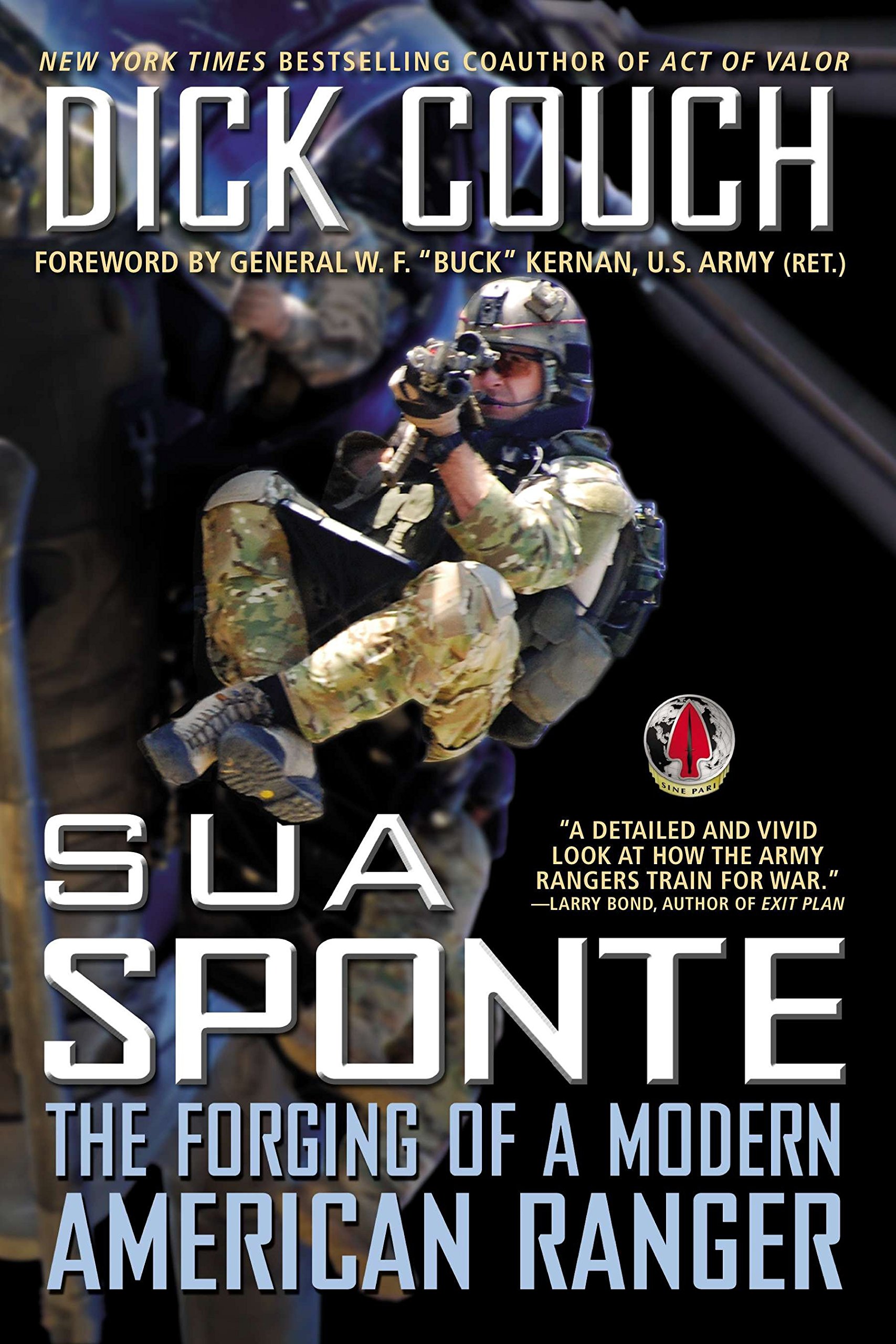

His name is Dick Couch. He’s a retired US Navy SEAL and the author of several books on America’s special operations forces. Today on the show, we particularly discuss his book Sua Sponte: The Forging of a Modern American Ranger.

We begin our conversation discussing the history and varied purposes of the military’s different special operations forces. Dick then explains how a soldier becomes an Army Ranger and why going to Ranger School isn’t the thing that makes you a Ranger. He walks us through the process of becoming a Ranger, including Ranger Assessment and Selection. We end our conversation discussing the role special operations forces will play in the future of America’s military.

Show Highlights

- Why is it important for civilians to understand how special operations units work?

- The misconceptions people have about our military’s special forces

- How the special forces differ from each other

- Dick’s opinion on who the most important special operating unit is

- How did these special forces come to be?

- How has 9/11 changed how these forces are utilized?

- Why Army Rangers aren’t as well known as SEALs

- What sorts of people are drawn to special forces?

- Do special forces soldiers require “soft” skills too?

- What does the future hold for America’s special forces?

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- What It Takes to Become a Navy SEAL

- The Navy SEAL Creed

- The Way of the SEAL

- Extreme Ownership

- WWII Watermanship Week

- How Leaders Build Great Teams

- The Power of Team Captains

- Ranger School

- 75th Ranger Regiment

- Battle of Mogadishu

- Make Your Bed, Change the World

- DickCouch.com

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Recorded on ClearCast.io

Podcast Sponsors

Brilliant Earth is the global leader in ethically sourced fine jewelry, and THE destination for creating your own custom engagement ring. From now until February 3, you’ll receive a complimentary diamond stud earrings with the purchase an engagement ring. To see terms for this special offer and to shop all of Brilliant Earth’s selections, just go to BrilliantEarth.com/manliness.

Candid Co. Clear, custom made aligners to straighten your teeth at home. 65% cheaper than braces, saving your thousands of dollars. Get 25% off your modeling kit by visiting candidco.com/manliness.

Ten Thousand Short. Your new workout shorts. From cross-training, to running, to weightlifting, these shorts can do anything. Four-way stretch means you’ll be comfortable, no matter what you’re doing. Save 20% by visiting tenthousand.cc and using promo code AOM.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast.

When people talk about military Special Forces, the Navy SEALs are often the first to come to mind, but there are several Special Forces in the military that have a storied history and play a fundamental role in America’s military defense. My guest today is the only person to have been allowed to audit and write about the training programs of the respected of Special Forces units of every branch of the military.

His name is Dick Couch, he is a retired US Navy SEAL, and the author of several books on America’s Special Operations Forces. Today on the show, we particularly discuss his book, Sua Sponte: The forging of a Modern American Ranger. We begin our conversation discussing the history and varied purposes of the military’s different Special Operations Forces. Dick then explains how a soldier becomes an Army Ranger and why going to Ranger School isn’t the thing that makes you a Ranger. He walks us through the process of becoming a Ranger, including Ranger assessment and selection, and we end our conversation discussing the role Special Operations Forces will play in the future of America’s military. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/armyranger. Dick joins me now via clearcast.io.

Dick Couch. Welcome to the show.

Dick Couch: Thank you.

Brett McKay: So you’ve written several books about America’s special operating forces. What got you started with that?

Dick Couch: Well, I’ve had a very interesting service career in that I spent time in both the underwater demolition and SEAL teams. And subsequent to that, I went and spent about four years at Central Intelligence Agency as a Paramilitary Officer. And I thought, “Well with this background I would love to write a book.” So I started on a spy book and I was partway through it when I saw a book on Navy SEALs on the shelf and I picked it up and I read it and it wasn’t about Navy SEALs, it was about some very brave sailors who were on river patrol boats. So I called the editor up and I said, “Gee, these aren’t Navy SEALs, these are somebody else.” And he said, “Well, Navy SEALs are really hot right now.” And I thought, “Okay, I think I get it.”

So I started writing about the Navy SEALs story. It turned out to be SEAL Team One and I never looked back from there.

Brett McKay: Why do you think it’s important for civilians understand how the Navy SEALs or other special operating forces work?

Dick Couch: Well, before 9/11, they were becoming more important, but they were another member in the mix of our ability to project power overseas and a part of our Department of Defense. Since 9/11, they’ve taken a more central role in the global war on terror. I think that they maybe get a little bit too much attention, quite often at the expense of some very capable and brave and much needed Army, Navy, and Air Force Marine personnel.

But they seem to be the focus for sure right now. And there’s, again, I’m certainly not the only guy writing about Navy SEALs now. And then they’ve made some very successful films on SEAL operations.

Brett McKay: As you said earlier, you found that book that the publisher purported to be about Navy SEALs, but it wasn’t about Navy SEALs, so it seems like there’s a lot of misconceptions that people have about special operating forces. What are some of the most common ones that you’ve come across as you’ve talked to civilians about your work?

Dick Couch: I think that Special Operations across the spectrum are various communities and the primary ones being Navy SEALs, Army Special Forces, the 75th Ranger Regiment, which is an Army organization in the Marine Special Operations Command. Each one of them are separate cultures. They have separate missions. There is some commonality in how they execute their missions, but they do very different things.

So I think that, and they’ve grown tremendously since 9/1111, and they’re very much, even as we draw down perhaps in Syria into Afghanistan, those special operators are still hard at work overseas.

Brett McKay: And so you mentioned some how they’re different and they have different cultures, so how do they differ from each other in sort of broad strokes?

Dick Couch: Well, let me start with the Navy SEALs. They have as many of them admit they’re Jack of all trades and master of none. They have a maritime portfolio, which means they have to be good in the water and they have a lot of their training is focused around the water. It takes about a third of the time to keep those combat swimmer skills in tact and up to speed there even though we don’t hear about him being used very often. They’ve got air operations to train for. They’ve got land warfare to train for, so there’s a very broad spectrum.

It takes about a year and a half to basically train and qualify a Navy SEAL and then perhaps another year of training with his operational unit before he’s ready to deploy. So it’s a long training pipeline. The specialty of SEALs are maritime operations, but it’s been primarily used in a direct action role, which means they’re out there on patrol looking for bad guys and dealing with them.

Army Special Forces, which is another culture in itself. I’ve said this much to the chagrin of my fellow SEALs, I think they’re the most important special operator on the battlefield because their primary goal is to train other militaries, other security forces. So if they do their job right, and they do it well, then we get to come home. So I think they’re very important. They take on a lot of combat roles and direct action missions like SEALs, but they’re primarily trainers.

The third Special Operations component I’ll mention are the 75th Rangers. The 75th Rangers are the best light infantry in the world. They have very short training period, perhaps two months to take a young infantryman and make him into an Army Ranger. And then he may have four or five months of pre-deployment workout. They don’t do a lot of things, but what they do is light infantry work. They’re very good at conducting combat assaults and they do that very, very well.

The fourth member of the Special Operations mixture in the ground combat area is the Marine Special Operations Command with the Marine Raiders. And they do in some ways, like the SEALs, they do a bit of everything over the beach work, in water work. They’re more of an agile expeditionary force and they do spend a lot of time like Army Special Forces in training other security forces.

But next to SEALs, I would say that, the Army Special Forces and the Marine Raiders are among the most highly trained Special Operations ground combatants that we have.

Brett McKay: Well I’d like to dig in more into the Army Rangers because you wrote a book about Sua Sponte, about them and about their training and their culture. But before we get there, what were the origins of America special operating forces? Did each branch, did it happen sort of organically and they saw a need where they need something a little more specialized, but then they sort of over time formalized it? Or was it from the get go, they knew they needed a very formal structured Special Operations and they started it?

Dick Couch: I think that, I mean, we can trace the origins with Special Operations back to Richard Rogers and Rogers’ Rangers that we remember from Spencer Tracy in Northwest Passage. But each of the components today has their roots.

As far as the SEALs go, they came from the Navy Frogman of World War II after the landings at Tarawa and the need for hydrographic data because we lost an awful lot of Marines because we didn’t know the coastal conditions that they were going to have to advance across in order to make these landings. The birth of the Navy SEALs happened in 1943 after the landings of Tarawa and we needed Navy Frogman, so that’s where the SEALs came from.

Army Special Forces, they can trace their roots maybe back to the special operators in the Civil War and the men who operated behind the lines. Formerly, they were kind of a Cold War organizations as we built a Special Forces capability to go behind the lines in case the Soviets came in and took Europe, then we’d have some people to go behind the lines and create partisan forces. So they’ve always been a training component, but they have their roots in the Cold War and certainly they were very well deployed in Vietnam.

The Army Rangers, again, they’re just an outgrowth of light infantry that is by extension, has been almost seconded from the Army to the Special Operations Command, and they rotate soldiers, good soldiers through the Ranger Regiment, back to the Army and back into the Ranger Regiment.

The Marines are new to the Special Operations mix. They came about in 2006. Secretary Rumsfeld suggested without taking no for an answer to that the Marines needed a Special Operations component. There were Marine Raiders two or three battalions of Marine Raiders during the Second World War. They were stood up at the insistence of President Roosevelt, whose son was a Battalion Commander of the Marine Raiders. The Marines have had kind of a checkered career with Special Operations and special units in general. The Marines feel that they, in among themselves are special and I have to agree with them. They are special. But they’ve built a very robust capability since 2006 and now I think they’re a very valued member of the Special Operations ground combat mix.

Brett McKay: So all these different organizations and forces have different goals, different objectives, different cultures. Would you say since 9/11 that there’s been more integration? You see SEALs working with Army Rangers, there’s more … what’s the right word I’m looking for? Collaboration, I guess is the right word.

Dick Couch: I don’t think so. They tend to operate with their own. They prepare as a team. They’re a very team centric organization. They sometimes some of the other ground combatants will be conducting a direct action mission or they might use an element of the 75th Rangers as a blocking force, but they typically don’t work together per se. I think that has to do with a … It’s not that they can’t, it’s just that they prepare. They know each other. Everybody has a role on a certain type of mission. They know how each others react. They have a commonality in their weapons, how their gears placed on their body and how they’ve trained up to do certain missions in a certain way. They almost don’t have to talk to each other. It’s not that they don’t operate together, and they have in the past, but by and large they pretty much stick to their own groups when planning and executing Special Operations.

Brett McKay: So I’d like to dig deep into the Army Rangers because as you said, thanks to I guess the Osama bin Laden raid, there’s bees filmsmade about Navy SEALs. A lot of people know about Navy SEALs, but the Army Rangers often get looked over. And, I didn’t honestly, before I read Sua Sponte, I knew hardly anything about Army Rangers. I just knew my barber was part of it, was an Army Ranger, and that was it because I saw as his patches on his on his wall.

So let’s talk about Ranger School. There’s a Ranger School, right?

Dick Couch: Right.

Brett McKay: But not everyone who goes through Ranger School is a Ranger.

Dick Couch: Well, there is a great misconception about Army Rangers and Ranger School. First of all, Ranger School is an Army leadership school. It’s a very difficult school. It’s a hard school. It teaches young Army officers that even though they haven’t slept or eaten or are very hard pressed, that they can still go out and make decisions, they can fight, and they can lead in very trying circumstances, so it’s a leadership school. If you go to Army Ranger School and you pass it, you are technically Ranger qualified, but you are not an Army Ranger.

Army Rangers are those who serve in the 75th Ranger Regiment. They have three infantry battalions, one special troops battalion, and they have a very high standard of in the execution of combat assault and light infantry tactics. Typically, a young Army Ranger will sign up, he’ll go to basic school, he will get his infantry qualification, he’ll go to Airborne School and then he’ll go to Ranger assessment and selection. It’s currently a two month process. You might think, “Gosh, that’s not too long, two month.”

But they have quite an attrition. It’s a very difficult period of time for these young men and that attrition is probably 75%. Only 20 or 25% will make it to the end and then they get their beret and they are an Army Ranger. The real making of that Army Ranger, he’s been through the school, we know he’s a tough guy, but he really learns how to be an Army Ranger when he gets this to his infantry platoon, his Ranger platoon and starts working up for combat deployment.

When I was with the Rangers, I never met a Ranger First Sergeant that didn’t have at least 12 combat rotations in. They typically are overseas for four months, back for eight, and they go again and again and again. I think one thing that distinguishes Rangers from the rest of the Army and the rest of Special Operations, they have a very strict adherence to what being an a Ranger and doing the right thing. They consider warriorship and the ethos of being a Ranger to be a very high calling, and they have very high standards, and they hold themselves to very high standards.

I remember one Ranger First Sergeant saying to me, “Our standards are just like Army standards. There’s no difference, but we enforce them to the letter.” And they do. They take a great deal of pride in that, and I have nothing but great things and great admiration for the 75th Ranger Regiment.

Brett McKay: Well, let’s talk a little bit more about Ranger assessment and selection. So you said it’s two months, high attrition rate. What does that process look like? Is it similar to BUD/S or is it different?

Dick Couch: And they run them right in the ground to see if they have heart. The best thing I can say is it’s a test for a man’s heart. Past that, the skill building has to do around combat shooting and shooting with somebody on either side of you at night under certain conditions. You have to have some sense of a team and awareness of those around you while you’re conducting shooting operations.

So it starts them down the road on being a good light infantryman and good at combat assault. Again, a great deal of what makes these young men into good Rangers are the pre-deployment training in their deployments with the Ranger veterans in their Ranger platoons, and their Ranger companies.

Brett McKay: So just to clarify something, you don’t have to go to Ranger School and get your Ranger tab to do the Ranger assessment and selection, correct?

Dick Couch: No, you don’t. And very few are. What will happen is a young man, he will probably make you make two or three combat rotations before he goes to Ranger School. You can’t become an NCO, E-4 Sergeant in the Ranger Regiment unless you have your Ranger tab. So these young men, they all want to go to Ranger School. They want to get through that. They have much lower attrition rate for the guys from the Ranger Regiment who go to Ranger School. But if you’re going to stay in that business and make a career of it and move up through the ranks, you have to have your Ranger tab, and they go at great lengths to see that everybody gets there.

We’ve talked about these as the progression of an enlisted soldier in the Ranger Regiment. Officers are assessed by a different program and every officer in the Ranger Regiment who rotates in and then rotates out, has to have that Ranger tab and that includes a … I know an officer came in, he was a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine who sought to the canine aspects of the Ranger business, and he was a good officer, but he was having to go to Ranger School to become a Ranger qualified to serve in the Regiment.

Brett McKay: So to respond to you kind of highlight different young men who go through Ranger assessment and selection. I mean cutting us a thumbnail, what are the type of men who are attracted to doing this?

Dick Couch: Well, I think that it’s kind of the same type that it attracted all Special Operations. I think they want to serve. They want to be in a unit that’s special. I think that they maybe it’s proving something to themselves. A lot of them come in because their dads or uncles or or mentors or maybe a high school coach was in the Army or it was an Army Ranger and they’ve seen something in that young man and said, “Here’s something you might want to consider or you might want to do.”

I get a lot of young men come to me thinking they want to be SEALs. And I said, “Well, that’s good and I wish you well and what have you. But, take a look at Army Special Forces, the Marines, but also take a look at the 75th Ranger Regiment. That’s a great place to … If you want to serve your country and be with what I consider a high quality organization, I can’t say enough about the 75th Ranger Regiment.”

Brett McKay: After a Ranger assessment selection program. They start going on combat rotations. And you said that, some of these guys can go two or three combat rotations before they even start Ranger School.

Dick Couch: Correct.

Brett McKay: What does a typical combat rotation look like for a Ranger? How long are they deployed?

Dick Couch: They’ll be deployed typically four months. Maybe if they overlap a little bit, they’ll stay for a five month tour or they may shorten it up a little bit, but they’re overseas rather quickly, only for about four months and then they’re back for about eight. But they’re making, like I said, when I was with the Ranger Regiment, they were going, some of them were going back on shorter tours than that, but they go back again and again.

And one once more, their mission is primarily combat assault. They also have another mission that they train for is airfield seizure. It’s a very highly orchestrated thing where they parachute in and take over an airfield and land aircraft and set up a small arms and defensive things so that they can take over an airfield just about anywhere in the world. So they maintain that capability. But in the battlespace in Afghanistan or Iraq, they’re primarily used for combat assault, small arms, and combat assault. Their work in Special Operations is primarily as blocking forces for some of our special missions unit, and some of the missions that might be conducted by Army Special Forces or SEALs.

Brett McKay: And do Rangers stay in a specific geographic location? I mean, so sort of like SEALs. There’s SEAL teams where they all kind of sit together in the west coast of the East Coast and-

Dick Couch: Well, the Ranger Regiment is located at Fort Benning. That’s where they have their headquarters. They have one battalion at Fort Lewis, the joint Fort Lewis base in Washington state. They have one battalion at Hunter Army Airfield in Savannah and actually two battalions at Fort Benning. And so they’re pretty much in those battalions and they go overseas as a battalion and come back as a battalion. The one special troops battalion has certain capabilities that they will deploy with the other infantry battalions to support them as they need it.

Brett McKay: And so I imagine in between deployments there’s training that goes on to keep their skills or learn new skills.

Dick Couch: There is there. It’s constantly, they get a couple of weeks off and then they start back in working up to deploy again. I talk with some of the platoon officers and platoon Sergeants and say, “How did these guys measure up tour after tour?” And he says, “About 20% of them, after their first deployment, we tend to let them go” just because they find out, not that they’re not trying their best, but doing that kind of work takes not only toughness and skill, it also requires a certain aptitude and talent and not everybody has it.

He might be a tough kid who can get through the initial training, but he may just lack what it takes to do the job. It’s a skill based profession. They expect certain things out of them on their second and third deployments and it’s not for everybody. So while there’s attrition in the basic training, there’s also attrition in the operational components because some of them just don’t measure up when it comes to running around with an automatic weapon at night and shooting with other Rangers in close proximity.

Brett McKay: With a Ranger assessment and selection, is that something that if you wash out, there’s attrition, can you try again? Or say you do that first deployment, and they say, “Well no, this isn’t for you,” can you try again or is it pretty much a done deal?

Dick Couch: I think they roll some back if they’re hurt or they’re injured or what have you. I’ve seen that several times. I think that sometimes somebody is … it’s clearly they’re not quite up to this, maybe it’s by youth or by conditioning, they’ll go back to the regular unit and try again. And I think the Ranger Regiment prides itself when they have somebody come to that training and it doesn’t work out for them, that they send that soldier back to his unit better than when he came there. So, there are some who try it once, if they don’t make it, come back and try it again.

Brett McKay: So besides Iraq and Afghanistan, are there any places where Army Rangers, part of the 75th, they’re doing a lot of combat rotations?

Dick Couch: I don’t think so. I only know of those deployments in those areas. I can’t imagine them not having some presence in Africa, especially in North Africa, northwest Africa and even Somalia type where we have our special operators deployed. I think they deploy in support of Special Operations wherever they are. And of course, we remember the Battle of Mogadishu where they were primarily Rangers involved in that engagement.

Brett McKay: So you mentioned Donald Rumsfeld earlier, and I remember back when the lead up to the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars, and those are going on. There was an emphasis placed on Special Operations or special operating forces. What role do you see special operating forces playing in the future of America’s military?

Dick Couch: Well, I think that remains to be seen. They have expanded their portfolio to things like weapons of mass destruction and counterinsurgency operations. It used to be a rather narrow focus. Now it seems to be expanding. I would like to think that again, this is just my opinion that as it becomes clear in areas like Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, that even if our best efforts are made, there may not be a clear cut solution or a victory to be won within those populations. So I would hope that we would scale back some of our deployment there because I’m not sure there’s a clear path to victory.

There are other issues that maybe needs to have more attention. It could be Chinese expansion into southwest Asia. It could be certain areas of Africa, and it could be, certainly the Soviets would like to expand into, maybe reclaim some of their lost empire. And we perhaps might need some special operators to train and be ready for those contingencies.

Brett McKay: Do you see any changes coming special operating forces and how they operate at all? Or is it sort of more of the same? There’s going to stick to that ethos that they have because it’s worked for, 50, 60, sometimes 100 years?

Dick Couch: I don’t know. I think that the threat defines the mission and how you train toward it and we’ve got some very good mountain fighters and what have you. Army Special Forces will always, they’re the largest of our Special Operations components. I think there’s always going to be a need to engage with and train other security forces, whether it’s in South America or Africa or where have you, or maybe even train Ukrainian forces against a potential Russian aggression there.

I think that SEALs probably, they’ve ignored a lot of their maritime capabilities and fleet support duties because they’ve been running around the mountains of the Hindu Kush chasing Taliban irregulars. So I think looking hopefully, and as an old warrior here, I’m thinking I’d like to see us have a less deployed presence, a little bit more of a manageable operations tempo as we deploy these people so that they’re not so hard pressed overseas and maybe a little more careful aligning of our Special Operations components that are in line with a more narrow definition of our national interest.

Brett McKay: You mentioned Army Special Forces, they focus a lot on training. That seems like it’s a job that requires a lot of soft skills, people skills. I mean all these special operating forces requires those kind of people skills, soft skills, but seems like Army Special Forces require that especially, someone who’s sensitive to the culture and thinking of systems and management. Is that the case like that? Does it attract that kind of person?

Dick Couch: I think it absolutely does. And of course I mentioned it takes about two and a half to three years to make a Navy SEAL. It takes maybe two years to make a Special Operations soldier. And my definition of a good Special Forces soldier, an Army Green Beret, he’s somebody who’s a people person. He’ll stop a car driving down the street just to talk to the driver. What’s your name? Where are you going? How are you? What are you up to? It’s not that they don’t want to do direct actions, but their primary thing is teachers. They have to understand people, understand other cultures, and a lot of their training and their role play in and how they go about it is to make that guy an outgoing person.

I’ve seen it when the in Special Forces training, I’ve seen a Green Beret instructors take a young kid aside and say, “Look, you’re a bit of an introvert. That’s not gonna cut it in the work we have to do here. And I want you going out on the weekends, go into a bar, whether you order a beer, a coke, it doesn’t matter. Sit down beside somebody and start talking to them and draw them out and find out where they’re from, what they do, what they like, what they don’t like, how they vote, what sports teams a root for.”

But you have to be a people person to survive in that business. Also, I would point out that the average age of a Navy SEAL platoon is maybe 28 or 29 years old, but the average age of a Special Forces age might be 32 or 33. They’re very experienced soldiers, and it takes a while to acquire those skills along with certain language capabilities that go with conducting the missions that they have to do it.

Brett McKay: How long does a career last for say a Green Beret?

Dick Couch: Well, they put in 30 years, and they may put in even more than 30 years if they are up to it physically. The physical demands, probably the pure pain-o-meter indication would be that Navy SEALs physically is the most grueling of the training pipelines, but Special Forces and Rangers and the Marines are not far behind them in the demands they put on it. Some of these guys, when they get up into their early 40s, mid 40s, they have all the tools they need to do this business, but physically that they just have to work harder at staying fit and staying in shape.

Army Special Forces, their business of training others that isn’t quite so physically demanding is perhaps some of the other disciplines, even with the Marines in their over the beach operations, and the things that they have to do to be physically fit to do the mission.

Brett McKay: There’s probably not a lot of 50 year old Army Rangers or Navy SEALs, but you’d probably see that as a Green Beret.

Dick Couch: Not so much. I think that there may be some who stay on who have had an enlisted career and then an officer career and have been able to stay on for a while. It just gets harder and harder to stay fit to do the due to those particular missions, especially if you’re in a line combat unit. If you’re in one of those operating platoons, you work pretty hard to be able to carry that 40 or 50 pounds of operational gear and to run up and down mountains and to go a couple of days without sleep. It wears you down. It is a bit of a young man’s game, but there’s an awful lot of those guys that are in their mid 30s and early 40s that managed to stay on top their physical conditioning and are still able to go out there and perform with the younger men.

Brett McKay: Is there some place people can go to learn more about your work?

Dick Couch: Well, as far as my work and what I write about you can go to www.dickcouch.com and there’s kind of a short squib on each of the books I’ve written. I’ve been privileged to be able to go to each of the Special Operations training venues and audit the class, walk through with a number of those going through their basic training and even into their pre-deployment training. So I’ve been very fortunate to do that.

As far as any current official data as to what do you do and where do you go to sign up, I think you go online. Each of the Special Operations components has an excellent website that tells you what you need to do and how you need to go about it if you want to be one of them. Past that, there’s any number of books out there on all Special Operations Forces, but I’m proud to say that I’m the only person who’s written who’s attended all four major Special Operations basic and advanced training venues and have been allowed to write about it.

Brett McKay: Well, Dick Couch, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Dick Couch: It’s been my pleasure. Thank you.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Dick Couch. He’s the author of several books. Today we discuss Sua Sponte. It’s available at amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find out more information about his work at his website, dickcouch.com.

Also, check out our show notes at aom.is/armyranger where you find links to resources. We can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM podcast. Check out our website, artofmanliness.com. We have thousands of in-depth well researched articles just about anything physical, fitness, personal finances, relationships, social skills, you name it, we’ve got it. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us review on iTunes or Stitcher, it helps out a lot. And, if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member you would think we get something out of it.

As always, thank you for your continued support and until next time, this Brett McKay, encouraging you to not only listen to the AIM podcast, but put what you’ve learned into action.