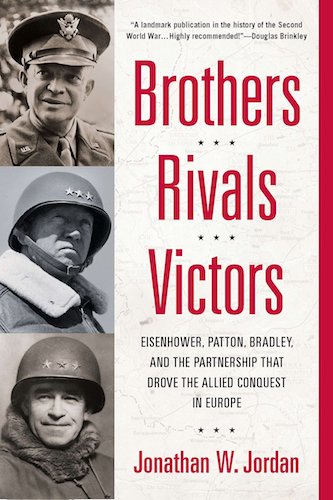

Eisenhower, Patton, Bradley. Three great U.S generals that led the Allies to victory in Europe during WWII. But WWII wasn’t the first time these three men met. Decades before they forged friendships and rivalries with one another that would influence their path to leadership. My guest today has written a biography of the complex relationships between these three men and how they impacted the tide of WWII. His name is Jonathan Jordan and his book is Brothers, Rivals, Victors: Eisenhower, Patton, Bradley and the Partnership That Drove the Allied Conquest of Europe. We begin our conversation discussing how these three men met — Eisenhower and Bradley (who Ike called Brad) at West Point, Eisenhower and Patton (who Ike called Pat) at Camp Meade after WWI, and Bradley and Patton at a military base in Hawaii.

Jonathan then explains the tension that existed between these three officers as each balanced personal career ambitions with the need to work with others, how each man understood the limitations of his fellow leaders, and how their friendships made them a stronger team.

We end our conversation discussing both the leadership weaknesses and the leadership strengths of each individual general.

Show Highlights

- How all 3 men ended up missing action in WWI

- How the tank brought Eisenhower and Patton together

- The early West Point connection forged by Eisenhower and Bradley

- Why Patton and Bradley never really connected socially

- What were the professional tensions like between these men during WWII?

- The multiple times Eisenhower saved Patton’s skin

- The point at which Eisenhower and Patton’s relationship became less than friendly

- Would the war have been different without these 3 men?

- The leadership lessons — both in the positive and negative — that we can take from these men

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- West Point 1915

- The Eisenhower Decision Matrix

- Leadership Lessons From Dwight Eisenhower

- The Maxims of General George S. Patton

- Patton’s Rules on Being an Officer and a Gentleman

- The Libraries of Famous Men: George S. Patton

- The Tao of Boyd: Mastering the OODA Loop

- American Warlords by Jonathan Jordan

Connect With Jonathan

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Recorded on ClearCast.io

Podcast Sponsors

Revtown. Premium jeans at a revolutionary price. Go to revtownusa.com/aom to have a chance to win a total wardrobe upgrade with two Revtown jeans and three Revtown tees.

Harry’s. Upgrade your shave with Harry’s. Get $5 off any shave set, for the holidays only, by visiting harrys.com/manliness.

Indochino. Every man needs at least one great suit in their closet. Indochino offers custom, made-to-measure suits for department store prices. Use code “manliness†at checkout to get a premium suit for just $359. Plus, shipping is free.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Eisenhower, Patton, Bradley, three great U.S. generals that led the Allies to victory in Europe during World War II. But World War II wasn’t the first time these three men met. Decades before they forged friendships and rivalries with one another that would influence their path to leadership.

My guest today has written a biography of the complex relationships between these three men and how they impacted the tide of World War II. His name is Jonathan Jordan, and his book is Brothers, Rivals, Victors: Eisenhower, Patton, Bradley and the Partnership That Drove the Allied Conquest of Europe.

We begin our conversation discussing how these three men met. Eisenhower and Bradley, who Ike called Brad, at West Point. Eisenhower and Patton, who Ike called Pat, at Camp Meade after World War I. And Bradley and Patton at a military base in Hawaii. Jonathan then explains the tension that existed between these three officers as each balanced personal career ambitions with the need to work well with others. How each man understood the limitations of his fellow leaders, and how their friendships made them a stronger team.

We end our conversation discussing both the leadership weaknesses and leadership strengths of each individual general. After the show is over, check out our show notes at aom.is/brothersvictorsrivals where you find links to resources where you delve deeper into this topic. Jonathan joins me now via ClearCast.io.

Jon Jordan, welcome to the show.

Jonathan Jordan: Thanks for having me, Brett. I’m a big fan of AOM’s podcasts.

Brett McKay: Well, I appreciate that. So you got a biography it’s … Okay, this is a history book, but it’s also a biography. It’s called Brothers, Rivals, Victors: Eisenhower, Patton, Bradley and the Partnership That Drove the Allied Conquest in Europe. When I read this book it’s really interesting because it’s a biography because you do do individual biographies about each of these men. But it’s also interesting because it’s a biography about the relationship between these three guys, Eisenhower, Patton, and Bradley. What led you to write about the relationship these three men had during … Well, I guess before the war and during the war?

Jonathan Jordan: Yeah. It was a long and intriguing relationship between Eisenhower and Bradley going back to really the summer of 1911. And then Eisenhower and Patton at the very end of World War I. And I didn’t set out to write a triography so to speak. I began reading about these guys because as a kid growing up in the 1970s, dad was off flying planes in the Air Force, and for better or for worse I’d spent a lot of time watching television. We only had four channels back then. And there were a lot of these World War II movies that were very popular. And so I’d see these heroic guys like Patton or Nimitz or MacArthur.

And as I got a little bit older, I wondered what were these guys really like when they weren’t heroically standing on the bridge of the USS Yorktown watching Japanese planes get shot down. When they went back to their offices, were they jealous, were they scared? Who did they blow off steam to? What happens when they take their helmet off and put their feet up on the desk? And so I started reading about Eisenhower, and Patton, and Bradley after that, and realized that there are some very fine biographies written about each of them. But what seemed to be escaping the story was their relationship with each other. While we’re not always necessarily defined by our relationships, relationships certainly do affect who we are and how we behave. I found out that this long and sort of evolving relationship between these three generals had a strong impact on the way World War II played out in Western Europe.

Brett McKay: Well, so let’s start talking about the relationships. Eisenhower and Patton, let’s talk about that relationship. You said they were friends before World War II right after World War I. How did that relationship start, and what was the attraction between the two guys?

Jonathan Jordan: Eisenhower and Patton were in some ways the odd couple. You wouldn’t normally expect to see them in the same circles together, because their backgrounds were very different. Patton grew up in a small wealthy family in Southern California. Never had to work outside the home. He had one sister who, sort of twist of history, dated General Blackjack Pershing and almost married him. But Patton had that deep sense of family history, social connections. He also grew up as an introvert.

Eisenhower on the other hand came from a middle-class family from Middle America Kansas. There were seven boys in his family. No girls. He had a very strong sense of community, unlike Patton. And while he was a tough kid, he also learned to rely on allies like his older brothers when dealing with the neighborhood bullies. So their personalities grew up very differently. They both went to West Point. And then after graduation, their careers were very different.

Patton had a meteoric career in the army after West Point. He became the army’s master of the sword. He was an excellent fencer. He redesigned the Cavalry Saber, represented the United states in 1912 Olympics in Stockholm in the Modern Pentathlon. He finished fifth. Then he joined General Blackjack Pershing’s expedition against Pancho Villa in Mexico. When he went off to World War I he commanded a tank battalion. But on the first day of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive a Mauser bullet found its way to him, and put him out of action. So, he missed most of the first world war.

Now, Eisenhower, he was a team sport guy. He loved baseball, especially loved football. He was a small-time football coach. During his playing career at West Point, he had been in some big games against Jim Thorpe who had played for the Carlisle Indians school then. This was his passion, team sports and especially football. But he had a knee injury while he was at West Point, and that put him on the sidelines. And essentially forced him to become a cheerleader, a manager, and a coach.

After graduating from West Point, Eisenhower, being kind of a small-time football coach at these little army posts, and that developed his training skills. He ended up missing World War I because the U.S. Army didn’t want him going off to fight the Kaiser, they wanted [inaudible] the other men to fight the Kaiser. And so Ike ended up training men with the U.S. tank corps in Camp Meade, Maryland. After World War I, tanks is really what brought the two men together. They both developed their initial professional interest based on this new snorting mechanical beast the army called tanks. They developed these theories about what a tank could do in the next war.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and we reiterate some of the things you talked about these guys, their personalities. So, Patton, yeah, I think a lot of people … He was an individual sport guy. You reiterate that throughout the book that he didn’t really do team sports. And I thought it was interesting too, you said he was an introvert, but this guy was larger than life. He did enjoy holding the limelight whenever he could get it.

Jonathan Jordan: He did. He used to say, “I’d rather be looked at than over-looked.” To Patton in some ways, there is to some extent no such thing as bad publicity, at least growing up. He would bring attention to himself at least in Eisenhower’s view through crude and obscene language. He’d liked to, as Ike once said, “To explode a few rounds of profanity in polite society.” If nobody paid any attention he’d just move on, but if somebody noted it or reacted to it, he’d keep doing more the same.

Throughout his life, General George Marshall’s wife, Katherine Marshall, and then Patton’s father, and Ike Eisenhower would tell Patton over and over, “You’ve got to watch what you say. You’ve got to have the gravitas of a senior leader.” And that pension for attracting sometimes bad publicity like nails to a magnet, was to dog Patton throughout his career. Patton, of course, could pay for any mistakes he made while the war was going on, and while he was generating victories. But in the absence of battles to fight in and win, it could be a problem for him. And as it is a problem for any modern general.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And we’ll talk more about that as we get into World War II, and we talk about how Eisenhower’s and Patton’s relationship developed then. So, let’s talk about this love affair for the tanks. Both these guys thought the tank was the future of warfare. But that butted heads, or went against army doctrine at the time, correct?

Jonathan Jordan: Yeah. After the first world war, and again, remember, Patton had fought in that some, Eisenhower did not. The two men looked at tanks as being a new device that could basically take the role of the shock cavalry from the medieval times, the armored horse. It could drive deep into the enemy’s rear echelons. It had a lot of shock power. And that went against army doctrine at the time, which based on the first world war said the tank is only there to support the infantrymen. And if the infantrymen can only move at a four or five mile an hour pace, then the tank doesn’t need to go any faster than that. So, they were kind of heretics for a while. And that heresy between Patton, Eisenhower and a few other of the real tank aficionados was something that brought the two men very close, and created a relationship that lasted almost to the end of their lives.

Brett McKay: As you said, these two guys were pretty much completely different. Eisenhower more about alliances, working with others, Patton wanted to be the star, an individualist. But as you’re talking about the book, both these guys missed the war, World War I. Did they talk about that? And did they think that their chance at … Or were they very conscious about wanting to do something great? They both wanted to be great generals, and did they talk about that after World War I? Are we going to get our chance?

Jonathan Jordan: Yeah they did. Patton and Eisenhower when they were stationed together at Camp Meade, used to talk about not if there’s another war, and of course World War I was called the war to end all wars. But they would talk about when the war came, and what would be their role. And they used to exchange letters. One point later on, Patton wrote Eisenhower and said, “In the next war, I’ll be the Stonewall Jackson and you can be the Robert E. Lee. Ike, you do the big planning, and you let me go in and shoot up the enemy.”

So, they believed that there would be another war, but like many officers, they were let down. Patton actually went into a sort of depression when he came back to the United States, because he felt that his great role was to be a great general. Eisenhower sort of had that feeling, though not as intensely as Patton experienced it, because Eisenhower was what you’d call a late bloomer. He became an intellectual on military matters as his relationship with Patton went along. And then as he developed his own mind through other mentors in his career. But the two men at first saw other folks coming back from World War I with chestfuls of medals and promotions, and there was definitely a sense that they had been short-changed.

Brett McKay: I thought that was interesting too that Patton even before World War II kind of predicted what the relationship would be like in a future war. Because that’s how it ended up. Patton was the Stonewall Jackson, and Eisenhower was sort of the big picture General Lee guy.

Jonathan Jordan: Exactly. And I think they both had a sense even early on that Eisenhower was a guy whose mind was broader than Patton’s. Patton loved battles, and he was very single-minded in that regard. As Eisenhower developed in the 1920s, he went to Leavenworth where the Command and General Staff school was. Went to the Army War college. And he developed a broad sense of what a war in a democracy requires. He learned about industrial mobilization. He wrote a paper on how to develop a citizen army based around the National Guard. And how you would do a mass mobilization if the country needed it.

When Eisenhower was stationed in Washington in the late ’20s and early ’30s he learned something about politics, and how the war department operated. He had mentors that Patton didn’t have, and he had a facility for learning from generals from sergeants from industrialists. How a big war would be run, and how we would run it with allies. Whereas Patton consistently came back to the theme of I want to command armies in a battle, and George thought of himself as a battlefield captain, as opposed to a chairman of the board that Eisenhower became.

Brett McKay: So, in this sense they were brothers. They had an appreciation for their differences. But at the same time there’s that rival component, and it seems like both of them, even early on in the relationship, kind of had a contempt for each other as well for their differences.

Jonathan Jordan: During the ’20s and ’30s when they didn’t have to run into each other too much, they both knew each other’s limitations, but they were also good friends. The families had spent time together at Camp Meade. The Eisenhower toddler was dotted on by Patton’s daughters. Beatrice Patton and Mamie Eisenhower knew each other. So they were social friends. They knew they could count on each other, but they were cognizant of each man’s limitations. And the way those limitations brushed up against their personal friendship grew into sharper focus the further up in the command chain they went.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about Eisenhower and Bradley. You mentioned they got to know each other in 1911 at West Point. How did that happen? Did they just go to school together? Were they playing football? What was going on there?

Jonathan Jordan: They both met each other about the same time they put on their cadet uniforms in August of 1911. They were both fairly tall for their age, so they were assigned to the same cadet company. They became very good friends, and it was mostly through their love of sports. Omar Bradley, like Ike, liked football. But his real passion was on the diamond, not the grid iron. Bradley held the record for the longest West Point throw for a long time. Throughout his college career he swung his Louisville Slugger to a .333 batting average. He was actually a little bit better student and cadet than Eisenhower. He outranked Eisenhower their senior year. But their love of team sports really cemented that kind of friendship.

The other thing that they had in common after graduation is that Bradley, like Eisenhower, totally missed out on the first world war. He was stationed with an infantry regiment in Montana and Iowa. Basically spent the war guarding a copper mine. And about the time his regiment was ready to ship out to Europe, the bells rang out in celebration of the armistice. So, both Ike and Brad thought that their failure to get into World War II had damaged if not possibly ruined their careers. They thought that for a little while.

Brett McKay: And tell us a bit more about Bradley’s personality. Because he’s a general that … He’s one of the greats, but unlike Patton or Eisenhower people sort of, I don’t know, ignore him or glance over him.

Jonathan Jordan: Yeah. He was the kind of guy who would never call attention to himself. Bradley grew up in a very poor part of Central Missouri. His father died when Brad was 14. And he had to shoot small game in the woods to sell to his neighbors to help make ends meet. His mother had to take in borders, so they weren’t prominent either socially or economically the way Eisenhower’s family was well known in Abilene, Kansas. And the Patton’s were a wealthy family.

When Brad was 17 he was involved in a skating accident that basically smashed up his teeth. And they didn’t have the money to get his teeth repaired. So he was always self-conscious about his smile. And if you ever see pictures of Omar Bradley, if he’s smiling he usually keeps his lips together. So with that kind of background, Omar Bradley never developed the social confidence of Patton who is wealthy and well-connected, or even in Eisenhower who grew up with a strong social net. While that’s something that as a kid you expect maybe will grow out of a little bit, and Bradley did grow out of that some. It came into sharper focus when he moved up to the very high levels of the army’s command structure, and had to work with the British, many of whom were well-educated. They spoke French, they were very socially self-confident. Because of that, Bradley was more the kind of guy who was comfortable teaching, teaching math, teaching his junior officers about a plan he had put together. He was more of the professorial type who liked to stay out of the limelight.

Brett McKay: And he was a team player. A big time team player.

Jonathan Jordan: Absolutely. Bradley believed that … That was what he loved in West Point and growing up. He was a baseball player. He believed there was a time for a certain amount of individual accomplishment, but it all had to be within the framework of a team. And that really came into sharp focus once the stakes became high. When the three men were commanding multiple divisions, and there were things going on in a big scale in Western Europe. So Bradley’s team orientation served him very well.

And it was reflected later on, because he grew up as the kind of general who relied on his staff members to do a lot of the work. He wasn’t the type to insert himself except in fairly isolated instances. If his staff told him that something was going on, or that something needed to be done, he generally took their recommendations, because he trusted them.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about Patton and Bradley. When did they first meet and start working together? Was it before the war? Did their relationship start when World War II started?

Jonathan Jordan: Well, Brett, prior to World War II, the army was fairly small. After 1920 we demobilized the World War I army. So the officer corps, even in the days before emails and texts and the internet, they were able to keep up with each other reasonably well. And Patton and Bradley first met each other in the mid-1920s when they were both stationed with the Hawaii division. Patton was organizing the trap shooting team. And a major named Omar Bradley showed up to try out for it. Brad was one of the army’s crack shots with the Springfield rifle. He went through his life being one of their better rifleman shotgun man. Bradley was a little bit nervous when he first started trying out. He missed the first two clays. But then after that he hit the next 23 in a row. And Patton was watching Bradley, and just kind of shrugged and said … Bradley remembered it with sort of a condescending tone, “Okay, I think you’ll do.” And that was their introduction. After that Brad and Patton never really hit it off socially. Because they just ran in very different cliques. And they had very different professional differences.

Patton grew up in the cavalry. That was sort of how he thought of things. A horse, of course, is a big beautiful animal, and it’s very strong and powerful. But it eats a lot of food, and it can get shot up on a battlefield if it’s left in one place too long. Patton’s mentality was that an army is a lot like a horse. You have to keep it moving. You have to drive toward the enemy rear, or it’s going to consume its supplies, and get shot up very quickly. So to Patton, attack, attack, attack was his method of operating.

Bradley professionally came up through the infantry. As an infantryman, Brad had a foot soldier’s appreciation for the vulnerability of the human body under fire. So, Brad took the approach of careful planning. He didn’t like to take unnecessary risks. He’d like to keep his flanks secured and keep good lines of supply. And he always wanted to make sure that there was a solid plan before he moved too quickly. So the personal differences, and the professional differences between infantryman Omar Bradley and horse soldier George Patton were other dividing lines between the two’s personality.

Brett McKay: And this would be, you’d see this throughout World War II. Let’s talk about that. So World War II starts. How did these three men connect there? Was it just by chance they all got assigned to Europe, or was that the way they started their military career, was destined that these three men would be working together?

Jonathan Jordan: It was the personal connections between the three prior to World War II that had a huge impact on their working together once the shooting started. Before World War II in 1940 to 1941, Eisenhower had come back from the Philippines. He’d been working as a staffer for MacArthur. He was kind of burned out on staff work. He really wanted to get into the field. And Patton had become the nation’s pre-eminent tank division commander. Eisenhower was basically begging Patton for a job as a regimental commander in Patton’s tank division. Throughout their correspondence, Patton said, “Look, I’d like to get you in any capacity as I can, Ike. You’re a smart guy. I’d love to have you as my chief of staff but if you want to take a chance then maybe the army will put you in as a regimental commander under me, and I’ll be happy to do it because you’ll be valuable.

But the army had different thoughts. And the army saw Eisenhower’s ability to plan, and General George Marshall pulled Eisenhower from a post in San Antonio, Texas up to Washington and said, “I need you to help me plan the invasion of North Africa.” Well, when Eisenhower was doing that he was in close proximity to Marshall. And one of the guys he wanted as his horseman in this three-ring circus of North Africa was George Patton, because Eisenhower trusted him.

When Eisenhower brought over Patton into North Africa, the Allies invaded. We were stuck in Tunisia for a while. And kind of the beginning of the movie Patton with George C. Scott starts out with Patton coming over to take over things in Tunisia. One of the people who was hanging around the American headquarters in Tunisia was Omar Bradley. Bradley had been sent from the War Department to serve as Eisenhower’s eyes and ears among the Tunisian forces. Eisenhower loved to have Bradley back with him because he trusted Bradley. Patton knew Bradley and said, “Look, instead of having you as Ike’s spy, I want you as my deputy commander. So that’s how that personal relationship that went back to the ’20s and even the 19 teens came back around full circle with Eisenhower moving up to being the supreme commander. Patton as the senior army commander, and then Bradley working under Patton as his understudy, essentially.

Brett McKay: It’s interesting because you mentioned there in the beginning before World War II started, Eisenhower was wanting to work under Patton. But then Eisenhower ended up being Patton’s boss. And so that was kind of interesting tension throughout the war. All three of these men were ambitious. They wanted to leave a mark in their military career. They wanted to gain rank. So what was that tension like when, say Patton was like, “Okay, yeah. Ike, come work for me.” But then Ike ended up being Patton’s boss, or Bradley ended up working under Patton, or then Bradley was Patton’s boss. What was that tension like throughout World War II?

Jonathan Jordan: In Eisenhower’s case it worked out pretty well, because Ike had a very different role from Patton’s. Patton’s was to capture an area, to destroy an army. He had specific missions to accomplish. Eisenhower had to sort of work in a supervisory role. So they were able to get along pretty well, but there was always that army chain of command that they couldn’t escape from. Occasionally, Eisenhower would tell Patton, “Look, you’re shooting off at the mouth too much. You’re ruining your credibility by acting like you’re just spouting off when you and I both know you thought about these things, but you say them in a flippant way. So you need to work on that. Work on your approach. Have some more gravitas. Work on your image.” And Patton groused about that. He thought Eisenhower was getting a little bit big for his britches. He wrote to his wife Beatrice that … Patton said, “I think I can do a better job as supreme commander. But I certainly don’t want the job.”

That relationship was always going to be a little bit tense, but it also had some benefits. Because later on when Patton got into trouble for some things he had done or said, Eisenhower would be there to protect him, because he understood Patton’s strengths, and wanted to keep Patton in the fight. He would also, as Eisenhower told General George Marshall, “When it came to controlling Patton and tempering some of his more damaging attributes, I can be rougher with Patton than anybody else could without my having to ask for them to be fired and sent home. Because of our friendship, I can give him sort of the straight scoop.”

Brett McKay: Yeah. There was some definite really … Eisenhower giving Patton the big time straight scoop. There was that one moment I think, or was it after the incident where Patton slapped the guy in the hospital. And he was pretty much on the chopping block. Eisenhower summoned him to the office, and basically said, “Look, I’m going to give you one last chance.” And Patton just started crying. Gave Eisenhower a big hug.

Jonathan Jordan: Yeah. Eisenhower done that a number of times. He had kind of a standard procedure for what he called jacking up George Patton. Patton had slapped a couple of enlisted men in two different hospitals in Sicily who he thought were malingering. The idea of post-traumatic stress wasn’t really a concept that Patton understood, and so that got him in a lot of trouble. Eisenhower went to bat with Patton. The newspapers were going to report that, and basically sink Patton’s career. And Eisenhower sat down with a journalist and said, “Look, I’m not going to censure any story you choose to write, but I do want you to know that Patton is very, very valuable to the Allied war effort. We don’t have very many generals like him. So you can write the story, but I want you to know that it’s going to be damaging.” And Eisenhower had such a good way with the press. And the press were very patriotic people. They considered themselves Americans first and journalists second. And they said, “Eisenhower, if you tell us that it’s going to hurt the war effort for us to print this story about Patton slapping people around, then we’ll not only bury the story, we’ll deny it existed.” And so Eisenhower saved Patton’s scalp that time.

Then about six months later, Patton got into trouble again. He had made some comments about after the war, the Americans and the English would rule the world. He apparently said, “And the Russians.” But the reporter who was listening to him didn’t pick up that part of the comment. And that created a big uproar in the American newspapers. And again, Eisenhower had to basically put George up on the scaffold, put his head down on the block, and then give him a reprieve of execution. And he can do that because he recognized Patton’s value to the team.

Brett McKay: Throughout the war, these guys remained friends. Whenever they would get together, they’d have these … They just stay up late into the night, early morning, drinking and just talking about the war, and just other things. But as you mentioned earlier, the relationship started to change. And those differences, those acknowledgments, and the limitations each man had became more focused. So how did that relationship change? Was there a moment when Eisenhower and Patton’s friendship ended, and it was just basically a professional relationship?

Jonathan Jordan: Yeah. There were a couple of flash points in their relationship. It morphed almost not just because of the positions they held, but also the jobs they were forced to do. In Western Europe in 1944 and 1945, Eisenhower’s job was to look out for the entire Allied force. And that include the British, the Canadians, a lot of people other than just the Americans. And his friend, Omar Bradley, as much of a team player as Bradley was, Bradley always had a little bit of professional jealousy, or at least some professional tension, with not so much Eisenhower, but with Bradley’s natural rival British general Bernard Montgomery, who was at the same level basically as Omar Bradley. And so when Eisenhower would do something that the two men felt favored the British, they would get together, they’d grouse about Ike. How he was basically gone native with the British. And that rubbed in Omar Bradley’s craw for a bit, and it really throughout the campaign through the fall of 1944.

And a flash point came up, and it was really something that was a harsh blow to their relationship during the time of the Battle of the Bulge. Now, in December of 1944, Omar Bradley’s First U.S. Army was hit in the center of its line by a surprise attack from the Germans. The papers called it the Battle of the Bulge, because it drove back the American lines. And it was a big blow to Bradley’s prestige. It was a bloody affair for the Americans. Because Bradley’s headquarters was south of the Bulge, but his main armies were north of the Bulge, Eisenhower took two of Bradley’s three armies. First and the Ninth U.S. Armies commanded by Generals Hodges and General Simpson and gave those to Bernard Montgomery.

And that infuriated Bradley. He called up Eisenhower and he said, “Ike, if you’re going to take my armies away from me, I can’t be responsible for this battle. I resign.” And Eisenhower who sensed that his old friend was blowing off steam and said, “Brad, your resignation doesn’t mean anything to me. You’re going to continue to do your job.” And he was able to placate Bradley a bit. He had Winston Churchill say some good things about Bradley in the House of Commons. And eventually Bradley was able to get his armies back. But Eisenhower did something he knew would infuriate his old friend because he felt that was what victory needed. During that time, it was a very tough blow to their personal friendship, but sometimes the guy at the top has to make those decisions.

With Patton, Eisenhower kept a pretty good relationship throughout the war. But then after the war, Patton’s mouth was getting him into trouble that he didn’t have any victories to offset. And in October of 1945, after the war had ended, Patton made some comments about being soft on the Nazis and hard on the Communists, and papers again got in an uproar. Eisenhower very sadly had to fire his friend Patton. He relieved him from command of the Third U.S. Army, and that really ended their relationship as friends. And Eisenhower hated to be the one holding the ax, but he felt that was what the Allies needed in the interest of political harmony.

Brett McKay: How did Patton and Brad’s relationship change throughout the war?

Jonathan Jordan: You know, Brett, that was an interesting kind of dynamic. Because Bradley started out his fighting career in the second world war as Patton’s understudy in Tunisia. Then they moved over to the invasion of Sicily, and Patton was the Seventh US Army commander. Bradley, again, was working underneath Patton. Patton was only interested in the attack, in the tactics, and not too interested in things like, how could Brad’s forces get air cover and air support? And what about the communication lines, and how do we get supplies to Omar Bradley’s men? Bradley found more and more things that he just didn’t like about Patton’s management style. And those really got under his collar.

When Bradley came back during a short leave to the United States, he spent a lot of time with General Marshall talking about the bad things that Patton was doing overseas. And it didn’t really change what happened with Patton, but it did make both Eisenhower and Marshall believe that maybe Patton wasn’t the guy to lead the invasion of Northwest Europe during Operation Overlord, the big D-Day invasion. Maybe we ought to use Patton in a striking role as kind of a cut and thrust cavalry type. But let’s let Omar Bradley start the invasion for the Americans.

Brett McKay: But it was interesting too. So, there was that … Bradley, I don’t know, sort of resented Patton for his differences. But at the same time, both Patton and Bradley had a disdain for Eisenhower’s … what they called his cozying up with the British. They didn’t think he was American enough. So they had that thing in common.

Jonathan Jordan: Yeah, exactly. They both had kind of a common enemy in Bernard Montgomery. Monty was a very selfish general. He was a type of person that not just Americans disliked. Some of his worst critics were the British Air and Navel commanders under Eisenhower’s supreme command. And during the Sicily invasion, Patton and Montgomery were equals. Montgomery ran the British Eighth Army, Patton ran the American Seventh Army. So they had this rivalry there. They always were worried about the British getting more credit, and belittling the Americans. And they felt the Americans had a right to show what they could do.

Then when we get to Northwestern Europe in the battles for France and Germany, now Bradley and Montgomery are on an equal footing. And it was Bradley who was grousing about Montgomery and Ike’s pro-Britishness. And while Bradley and Ike always had their friendship, and it never really changed that much at least until the Battle of the Bulge. Both Patton and Bradley sort of had this common foe that they could grouse about with each other without having to worry whether that was going to be something that they would differ about later. They both had a common enemy.

Brett McKay: How do you think these three men’s relationships … It’s really interesting because it was like there’s Bradley and Patton teaming up against Eisenhower in some instances. But then Eisenhower … They were all working together. How do you think that relationship influenced the war? If it weren’t for these three guys being together, do you think things would’ve ended up differently? I know that’s kind of hard to guess.

Jonathan Jordan: Yeah. Even in a what if scenario, I think if you looked back to what Eisenhower thought and wrote after the war about his different generals, he saw Patton as being one of America’s greatest pursuit generals ever. Kind of like Napoleon’s Marshal Murat. Just a guy who would overcome any obstacle, and chase the enemy down, never give him rest, and hound him. And so when looking at what we ought to do to invade Hitler’s Fortress Europe, Eisenhower thought of Patton as the kind of guy who we shouldn’t put into a static fight. We don’t want him as a close in slugger. We want him as somebody who can go tear into the enemy. So, the question was, who would be our close in slugger? Eisenhower believed that Omar Bradley was the right type for that.

The thing that their relationships did was give them a good picture of each other’s strengths and weaknesses. And so Eisenhower would be able to tell General Marshall back in Washington, Patton is the right guy for the role of a deep pursuit. And Patton did that when he charged through the Loire Valley, charged up to the Seine River, helped enable the capture of Paris. He was the kind of guy who we want in that role. And Omar Bradley is the one who we want for a slug fest. Whether it’s along the Siegfried line of Germany, whether it’s in the hedgerow country of Normandy. Eisenhower said, “I trust Brad to be the right guy with the right balance to be able to get the job done.”

Brett McKay: So, this is a biography of relationships, but this is also three separate biographies of three great leaders. I’d like to talk about what do you think are the big leadership lessons we can take from each of these guys? What they did well, and what did they do poorly. So let’s start with Eisenhower.

Jonathan Jordan: Yeah, with Eisenhower, Brett, one of the best leadership lessons is that once you’ve got a cause that you can believe in, that you can put your heart into, it’s important to subordinate yourself to the greater good. Eisenhower had plenty of times when he would come back infuriated, red in the face, swearing up a cloud of cuss words. And he could cuss as well as Patton could over General Montgomery. Montgomery was just the kind of guy who would infuriate people, and Eisenhower time and again subordinated his temper. He played nicely with Montgomery and supported him wholeheartedly when he felt that that was what was necessary for victory.

I think another lesson from Eisenhower is that leadership comes in many forms. Ike always wanted to be the field general. He wanted to be a guy kind of like Patton who would get out and could direct a battle. But what he learned over his career is that sometimes what we’re good at, and sometimes what we want to do are two different things. And Eisenhower learned that while he may have envisioned a general as a person who points to a spot on the map and says, “We will attack here.” He learned that there are different forms of leadership. And his had to be the type of leader who is a conciliator, who could understand the problems that the Navy, that the Air Force, that the logistical people, the civilian infrastructure had. And he could make sure that everybody was happy enough to play together, and to get what they needed to get the job done. Eisenhower was basically the type who today we would see as like a chairman of a big Fortune 50 company. And he had a skillset that the other two didn’t have.

Brett McKay: And what about Patton?

Jonathan Jordan: With Patton there are a couple of lessons here that get overlooked in this two-dimensional character we have that is really marked by the way George C. Scott portrayed him in the 1970 film.

The first one is that to be successful you’ve got to have a lot of depth. You’ve really got to put your thoughts, your mind, your reading into what you’re doing. Patton, we don’t really see this much in either the movie Patton or our popular image of him, but he was very much an intellectual. He read a lot of history. He incorporated historical lessons into what he would do, the plans he would make. He was the type of guy who when driving down a countryside in the car he would look out at the terrain and think, “How would I defend that? How would I attack that?” Patton had an awful lot of intellectual depth that underlay the dashing things he did, and the things we remember him for, the relief of Bastogne, the conquest of Messina in Sicily and so on.

But the other lesson from Patton is kind of a negative one. And that’s that you can have a lot of depth, but if you don’t portray that yourself as someone with that depth, if you don’t project that depth, then it can get lost in your message. And time and time again, Patton would have problems with what he would say that would get in the way of his message.

Great example of that is when Eisenhower, Bradley, and Patton were trying to figure out what to do with the Battle of the Bulge, how to respond to the Germans. Well, when he got to Patton, Eisenhower said, “George, what can you do? We’d like to make an attack north from your sector. How soon can you attack?” And Patton said, “I can move in three days with three divisions. Well, everybody in the room knew that you couldn’t really do that on the fly. There were too many plans that had to be set. You had to figure out road networks, and who got to use them. You had to stockpile supplies. Everybody knew that Patton was just spouting off about how soon he can get to Bastogne and save the 101st Airborne that was holed up there against the Germans.

Well, what they didn’t realize is that before Patton had come to meet with Eisenhower, he had talked it over with his staff, he said, “Let’s come up with contingency plans.” And he did an awful lot of groundwork there that the other people in the room didn’t know about, the British and Eisenhower’s other staffers. And so when Patton sort of popped off a, what looked like a flippant remark, it undercut the fact that he had done a lot of homework before giving that answer. And so projecting that kind of seriousness is something that hampered Patton’s effectiveness as brilliant as he was as a field commander.

Brett McKay: And what about Omar Bradley? What lessons could we take from him?

Jonathan Jordan: With Bradley, one of the best lessons is that once you get a team of smart people together, you have to trust them to some extent. The high point of Bradley’s career was Operation Cobra. The Allies after D-Day, we think of the longest day. In Saving Private Ryan we see that heroic struggle to get across the beaches. But once we were across the beaches, we were stuck in this hedgerow country of Normandy. And we couldn’t figure out a way to get out. The Germans were just defending too tenaciously.

And Bradley came up with this idea for a breakout. Before he unveiled that as a plan, he talked it over with his staff. He talked it over with people he trusted. And once he was sure of it, he prepared a very short plan. It was only one page long, and it had a big diagram. And basically said, “Here’s what we’re going to do.” He trusted the people he was working with to understand the plan and to execute. One of Omar Bradley’s strengths throughout his life was his ability to put together a great team, and let them do their jobs.

Brett McKay: What do you think his weaknesses were?

Jonathan Jordan: I think Bradley’s greatest weakness was his inability to assert himself. He would often times kind of let events go a little bit further along than he would’ve liked. In the case of his armies being moved over to General Montgomery during the Battle of the Bulge, he sort of heard rumblings about that and he didn’t get out in front. He didn’t recognize the threat.

It’s almost like what in modern parlance we might talk about the OODA loop, observe, orient, decide and act. He was a little bit slow to get to that when dealing with a threat from within. If Eisenhower was going to cut his supplies, or move armies to somebody else, Bradley didn’t assert himself as quickly as I think he wished he had in hindsight.

Brett McKay: We didn’t talk about Eisenhower weaknesses. What do you think his leadership foibles were?

Jonathan Jordan: You know, Eisenhower is a tough guy to be too critical of. The big criticism leveled against him by Montgomery, as well as many Americans, including American historians, is that Eisenhower never really had much command experience. And as a result, he didn’t have what Montgomery called battle grip, or the ability to jump in there and say, “I want you to do this. I want you to do that. We’re going to all stay faithful to these instructions.”

Now, the British were used to very detailed instructions. The American system was to give a broad objective, and let your subordinates handle it. I think the problem that Eisenhower ran into occasionally is that things might go a little bit eschew, and he was reluctant to jump back in there. The Battle of the Bulge was a good example of him taking a laissez-faire approach until it was obvious that he needed to jump in there. And he might have jumped in a little bit quicker than he did.

Brett McKay: Where can people go to learn more about your book and the rest of your work, Jon?

Jonathan Jordan: Well, the book Brothers, Rivals, Victors, and its follow up American Warlord, they’re available on audio and print at Amazon, Indie Books, the other places where you get books. I’ve got a Facebook page, Jonathan W. Jordan, author page, and website jonathanwjordan.com. I’d love to hear from you.

Brett McKay: And what’s American Warlord about?

Jonathan Jordan: American Warlords is kind of the follow up about the relationship, and how an even more fractious group, Franklin Roosevelt, Secretary of War Henry Stimson, General George C. Marshall, and the irascible Admiral Ernest J. King, all worked together. They set aside very deep political, personal, and professional differences, and managed to cobble together an alliance with the British that was able to marshal America’s resources, and defeat Fascism not just in Europe, but also in Asia.

Brett McKay: Well, I’ll have to check that one out. That sounds fantastic. Well, Jonathan Jordan, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Jonathan Jordan: Hey Brett, a pleasure from here as well, and thank you very much.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Jonathan Jordan. He’s the author of the book Brothers, Victors, Rivals. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find out more information about his work at jonathanwjordan.com. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/brothersvictorsrivals where you find links to resources, where you delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. And if you enjoy the show, you got something out of it, I’d appreciate it if you take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. It helps out a lot. And if you done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing this show with a friend or family member who you think would get something out of it. As always, thank you for your continued support. And until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.