When many people think of the American involvement in WWII, they likely bring to mind the 101st Airborne Division (aka the Band of Brothers) and their heroics at Normandy. But there was another American infantry division that took part in the largest amphibious assault in world history (no, it wasn’t D-Day) and then fought a year in Europe before the 101st even showed up. All in all, this division saw over 500 days of combat. They were the Thunderbirds of the 45th infantry division and my guest today was written a captivating history of this oft forgotten group of soldiers.

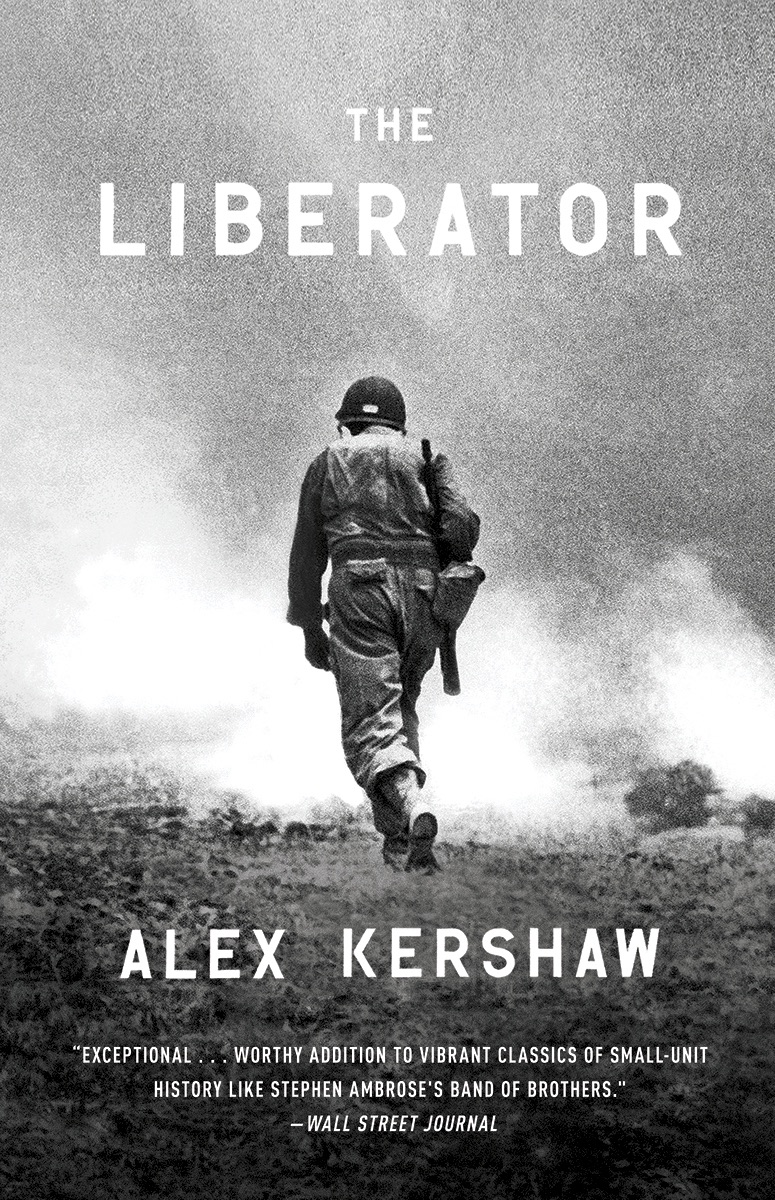

His name is Alex Kershaw and he’s written several books on WWII. The book we discuss today is The Liberator: One World War II Soldier’s 500-Day Odyssey from the Beaches of Sicily to the Gates of Dachau. Alex begins by sharing what made the 45th different from other infantry divisions and discusses why they’re often forgotten. He then talks to us about a colonel from Arizona named Felix Sparks who always led from the front and fought side by side with his men for over two years. We get into some of the major battles the 45th encountered and their liberation of the concentration camp at Dachau. Alex ends our conversation with a call to all of us reach out to a WWII vet before they all leave this life (which is not far off).

Show Highlights

- How Alex got into writing WWII stories

- What made the 45th different from other divisions?

- The interesting story of the 45th’s insignia

- The cultural and geographic makeup of the 45th

- What the Nazis thought of the 45th

- Why the 45th doesn’t get much recognition, despite their 500+ days in combat

- Who is Felix Sparks?

- Why Kershaw considers Felix Sparks the most inspiring figure of WWII

- The story of the Battle of Anzio

- How Sparks dealt with incredible losses in his division

- Why Sparks’ leadership was so compelling

- How the men reacted upon coming to Dachau

- What Kershaw considers the greatest achievement in American history

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- The Bedford Boys by Alex Kershaw

- Battle of the Bulge

- Operation Torch

- Battle of Anzio

- Podcast: Untold Stories from the Band of Brothers

- Dachau

- The Day of the Americans

Connect With Alex

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Hobo Bags. Dopp kits, wallets, messenger bags — if you need a new leather carry system, Hobo is the place to look. Visit hobobags.com/manliness and the code “hoboartofmanliness” at checkout for 10% off all regularly priced items.

Indochino offers custom, made-to-measure suits at an affordable price. They’re offering any premium suit for just $359. That’s up to 50% off. To claim your discount go to Indochino.com and enter discount code “MANLINESS” at checkout. Plus, shipping is free.

Squarespace. Get a website up and running in no time flat. Start your free trial today at Squarespace.com and enter code “manliness†at checkout to get 10% off your first purchase.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. Now when many people think of the American involvement in World War II, it likely brings to mind the 101st Airborne Division and the heroics at Normandy. But there was another American infantry division that invaded Sicily and then fought a year in Europe before the 101st even showed up. All in all, these soldiers saw over 500 days of combat. They were the Thunderbirds of the 45th infantry division. And my guest today has written a captivating history of these off-forgotten warriors. His name is Alex Kershaw and he’s written several books on World War II. The book we’ll discuss today is called The Liberator. Alex begins by sharing what made the 45th different from other infantry division and discusses why they’re often overlooked by people. He then talks about a colonel from Arizona named Felix Sparks, who always led from the front and fought side-by-side with his men for over two years. We get into some of the major battles the 45th encountered in their liberation of the Dachau concentration camp. Alex ends our conversation with a call to all of us to reach out to a World War II vet before they disappear from our ranks forever.

After the show’s over, check out the show notes at aom.is/liberator.

Alex Kershaw, welcome to the show.

Alex Kershaw: It’s great to be with you.

Brett McKay: So you’ve made a career for yourself, writing books about World War II. Curious, when did that get started and what led you to that particular topic?

Alex Kershaw: Well, I’ve been a journalist really since my early 20s and I have to say, I’m 51 now, so it’s been quite a while, 30 years almost. In my late 20s, I did an investigative story, quite a long story, took several months, about the Channel Islands in the English Channel. They were the only part of Britain that was occupied by the Nazis. And I realized when I was doing the story that number one, it was very, very enjoyable. I love being a journalist, especially an investigative journalist.

But also, I loved writing about World War II. And this back in the 90s, when there were a lot of people, obviously, a lot of people who had fought in World War II or lived through it, was still in their seventies. So I really got a buzz out of it. I really loved writing story. And I realized that I’ve always been fascinated by World War II. Both my grandfathers were in World War II. It’s the best story of our time. There’s no greater story, I believe, certainly if you’re an American. And I was like, “Why would I want to write about anything else?” These warriors are still amongst us, these giants among pigmys are still amongst us. And while they’re still alive, why not interview them? Why not tell stories about this wonderful period? Why not … Everything else didn’t seem to come close in terms of drama and emotional interest for me.

So I had the opportunity when I was in my early 30s to write a biography of World War II’s greatest combat photographer. That’s Robert Capa, an absolute legend. And when I was researching and writing that book, I came across a story of the Bedford Boys, which is the story of 19 young men who were killed on D-Day in the first way. The movie Saving Private Ryan is based on a few elements of my narrative. Or whether I should say that Saving Private Ryan recreates what happens on Omaha Beach, where my guys died. So anyway, that was in my early 30s and I’ve been extremely fortunately, touch wood. I’m actually touching my forehead right now. I’ve been very, very, very lucky indeed to be able to spend the last couple of decades writing about amazing people and writing about a period that is just something that I have always been fascinated by. I mean, it’s been wonderful.

Brett McKay: That’s fantastic. Well, the book I’d like to talk about in particular today is one called The Liberator.

Alex Kershaw: Right.

Brett McKay: It’s about the 45th infantry division in World War II. And it’s a division as we’ll see, played a huge role in World War II. But doesn’t get a lot of attention or credit, I would say.

Alex Kershaw: No.

Brett McKay: To start off, what made the 45th different from other divisions in the Army?

Alex Kershaw: I think there’s only one major difference, and it’s an important one because it really goes to the heart of what that division’s was about. And that’s that the 45th infantry division, nicknamed the Thunderbird Division because they had a shoulder patch, a beautiful soft felt Thunderbird patch on their shoulders. That division had more Native Americans among its ranks. So I think, a sole combat division is around 14,000, 15,000 guys, round about 7000, 8000 will actually see combat. But in that division when it left the US to go to Europe in World War II, there were over 1500 Native Americans. And those Native Americans were drawn from predominantly the west, Oklahoma, Colorado, New Mexico, those areas. And so I think that at the heart of that division, I mean, you can’t get much more quintessentially American than 1500 braves. And I would definitely call them braves, going over to Europe and fighting and being very proud of their heritage and their statuses as the original Americans.

Brett McKay: And part of that Native American heritage, I thought this was an interesting story, too. An interesting tidbit. So their insignia was the Thunderbirds, like a Native American Thunderbird. But before that, it was something completely different. Can you tell us a little bit about that and what happened?

Alex Kershaw: It’s essentially a quite amazing story because up until, I think it was about 1938, whenever Memorial Day or whenever these guys paraded from the 45th division in any small town in America, if you can imagine this, they had a swastika as their shoulder patch. So in 1938, you’d have these Americans marching in uniform proudly with a swastika on their shoulder. What happened is people realized this might not be a very good thing in combat and actually, it was in the late 30s anyway that they decided to change the swastika and put a Thunderbird patch on the shoulder. Now the Thunderbird is a symbol which is not just special to some Native Americans. It’s also through our history, been a very symbolic and going back hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of years.

But two important things to say about that Thunderbird image. The Thunderbird represents a really potent force. It’s a potent for good if it’s harnessed in the right way, directed in the right way. And it can be an avenging force. It can be a very powerful and destructive force, also when applied against the appropriate enemy. I was always very taken by this idea that we had these Native Americans fighting alongside recent generations of immigrants in America against the ultimate evil of the 20th Century, which was Nazis. And I know some people might say Stalin is just as bad, but as a European, I’m a European, you can tell from my accent. I don’t think there was a greater evil than Nazism. And it was very important to me as a storyteller and I think it’s very important for those who appreciate the sacrifice of ordinary working type of Americans in World War II to think that those guys, and some of them were Native Americans, those guys liberated Dachau, the Nazi’s first concentration camp in April 1945. So you have these guys with this very potent symbol on their shoulder that avenges the citizen soldiers for America, entering, liberating, and actually saving thousands of victims of Nazis right at the end of the war.

Brett McKay: So this is interesting contrast. You have this division where there’s a lot of Native Americans fighting Nazis who look down upon Native Americans as less than. How did that idea that the Nazis were fighting Native Americans and other, you know, I’m sure there’s Hispanic Americans in there as well … How did that color the Nazis’ perceptions of the Thunderbirds? They think like, “Oh yeah, these guys are just going to be a cake walk to me because we’re the superior race?” Do you have any insight from there?

Alex Kershaw: Yeah, actually I came across a quote from a German general. I think it was when the Thunderbirds fought in Italy. They fought from the 10th of July, 1943 right to the end of the war. Every day that Americans fought and died to liberate Europe, the Thunderbirds were there. I think it’s 511 days in combat overall. If you can track that with the famous Band of Brothers, 101st Airborne. I think 101st Airborne were on the line, able to get shot up for about 117 days. That just shows you how the 101st Airborne did not win World War II. Band of Brothers, those guys did not win World War II, certainly from the American point of view if there was anything else. But anyway, the Germans were the victims of enormous propaganda. Goebbels’s propaganda supremo, was a very, very sophisticated … actually a very intelligent man, did everything within his power to convince all Germans: German soldiers, German civilians that this was a just war, and that they should fight to the very, very bitter end. To the last man in many cases.

He was very adept at convincing ordinary Germans that the enemy were half breeds. That they were a made up of gangsters and half breeds, that the American fighting forces were weaker because they were not pure Aryans, they were not pure Teutonic warriors like the German forces. In fact, you could argue that the very strength of the American forces was their diversity. I would argue that the strength of American society is it’s diversity and always has been. It’s the ultimate image and culture, and it should always be that way.

Anyway, they were very condescending and had a little hubris when they went in to combat. I think the perfect example of this is the Battle of the Bulge, where the Germans were convinced that they were fighting an inferior enemy and December 1944, they were given a very profound psychological shock when they realized that they were not fighting an inferior enemy, that actually the half breeds would stand, and hold, and fight, in some cases to the last bullet. They were very, very fierce warriors indeed, in some cases. And that had a big profound effect in January of 1945 on the ordinary German soldier. They’d been told that they were up against an inferior enemy and to discover that that enemy was not inferior, but in some cases, awesomely fierce and stubborn, that had a big effect on the ordinary German in the Wehrmacht in early 1945, when there was a … they lost half in many cases.

Brett McKay: You mentioned earlier that the 45th spend over 500 days fighting. The 101st, a little over 100 days, yet as we talked about earlier, the 45th doesn’t get a lot of recognition.

Alex Kershaw: Yeah, no. I think the quote of point is that most people that know a little bit about WWII know a lot about D-Day, June the 6th, 1944. They know something about the Pacific: Pearl Harbor, dropping of the atomic bomb, etc. But a lot of people don’t realize, Americans started to fight and die in the European Theater in November of 1942. So we’re actually about 75 years, almost to the day, from the moment when Americans started to lay down their lives to restore democracy and human rights in Europe.

Operation Torch for them in 1942, the invasion of Sicily, which is actually the greatest amphibious invasion of the war, in terms of American men sent in to enemy territory. Over 200,000 allied soldiers in the invasion of Sicily in 1943. Salerno, that’s mainland Italy, that’s September 1943. A very, very, very difficult battle indeed. We almost had our backsides handed to us and were thrown back in to the Mediterranean. Then you have Anzio, January 1944. Again, a very, very, very difficult, bloody affair. And that’s … Anzio is January 1944, then you have June 1944, which is the one and only D-Day. The invasion that everybody remembers.

So the Americans were involved in several amphibious invasions before D-Day. Before the 101st Airborne went in to action. Let’s not forget that June the 6th, 1944, the day of days, was the first time that the 101st Airborne saw action in WWII. So from July 1943 right until June of 19 … sorry, it’s July of … yeah, July of 1943 right through until June of 1944, that’s an awful long time. That’s almost a year of combat when Americans were engaged in Sicily and Italy in very, very difficult fighting. Very, very hard battles. Very hard fighting. And it’s been forgotten about.

I was in the Anzio-Letuno graveyard just a few weeks ago. Seven and a half thousand Americans buried there. I was there on a beautiful Fall day, I think there were only three other people in the graveyard. About a week later, I went to graveyard over Omaha Beach, Colleville-sur-Mer, and there were hundreds of people in the graveyard. So the Italian campaign … Sicily and the Italian campaign, has rightly been called The Forgotten War, and yet it was probably the hardest fighting Americans were involved in Europe in WWII.

Brett McKay: We’ll get in to some of the specific battles, especially on Anzio, because that was one of my favorite sections. The writing was fantastic. But one character you follow throughout this campaign of the 45th, all the way from Sicily to Germany, is a guy named Felix Sparks. What’s his story, and what was his role as a commander or leader in the 45th.

Alex Kershaw: Well, it started off towards a captain. He became a company commander at the end of the Sicilian campaign. He landed on the 10th of July 1943. He was in the executive office of that company, Company E of the 157th Infantry Regiment of the 45th Infantry Division. His job was to keep records to make sure that people got the right medal recommendations. It was a desk role, and he hated it. He actually demanded that he be given a leadership role. He wanted to lead men in combat, and he got his wish. From September 1943 with the invasion of Salerno, he was company commander.

He remained a company commander right through until the Summer … actually the early Summer of 1944, became a battalion commander, and was a perfect example of the kind of meritocracy that you get in the US military, and certainly during combat. If you’re good enough, and you can stay alive, you’ll be promoted if you get the job done. And he was really, really, very good at getting the job done. He would be given very difficult tasks and would carry them out. He loved being a company commander most of all because that’s about 200 guys. With 200 guys, if you command 200 guys, you can get to know each one, you can get to know who their families are, you can form a personal bond with each of the men that you lead in combat.

And he loved that. He said to me, when I interviewed him for the book, that that was the greatest job he ever had, to be a company commander. A captain of the company in combat. So he fought all the way through. He fought through Sicily, Italy, Southern France, all the way up the Rhone Valley in to Germany, and then was the commander officer, the American commanding officer of the first Americans to enter and liberate Dachau Concentration Camp in April of 1945. So in terms of an epic odyssey, a really long journey, almost 2,000 miles, over 1500 guys, under his direct command, took orders from him in the battlefield were killed during this time in combat. He was on the line … in Europe for over 500 days of fighting.

Just an amazing story. He said it was a miracle that he survived. He often … I use the word often not lightly, it was many times when he thought he wouldn’t make it, that he would almost certainly be killed. It’s an extraordinary story of a working class American that grew up in the Depression, that was given nothing, and everything he got in life through hard work, and risk taking, that lead men very, very, superlatively well in combat. I couldn’t find … as I was researching this story, in the 20 years that I’ve been writing about Americans in combat in Europe, I couldn’t find a better example of someone that was more respected, and tougher, and more admirable that I’ve interviewed, and I’ve interviewed a lot of really extraordinary combat leaders.

Brett McKay: So let’s get in to some of the specific battles that the 45th encountered … the Thunderbirds encountered. We talked about Anzio. This was in Italy, correct?

Alex Kershaw: Yeah. It’s just about 60 miles south of where I am on the coasts. The idea for Anzio was that the Allies had been dropped by the Germans. The Germans were absolutely … really, really fantastic at defensive warfare, and if you look at a map of Italy, you’ll notice that it’s just basically two thirds of the country from the tip … the Mediterranean tip, all the way up the boot of Italy is one mountain range after the other. So what the Germans did was they’d set up a defensive line, the Americans would always be on the attack. They’d kill all the Americans, and they’d retreat to the next mountain range, set up the defensive line, the Americans would attack, and so on.

So it was a very, very bloody and very difficult campaign for the allies. To try and end this campaign quickly and seize Rome, the Allies came up with an idea that they would launch an amphibious invasion, hop around … do an end run around most of the mountain ranges in Italy and come in and attack it towards Rome, and land American forces at the closest point they could get to Rome, which was Anzio, Nettuno. The two actually today are rather pretty coastal, seaside towns in Italy.

So they landed … they didn’t land enough men. It was a botched operation from the start. Didn’t have enough landing craft. Everything was done on a shoestring. The invasions … the landing forces stalled. They didn’t take certain objectives in time. Certainly, they didn’t take heights. They were looking the plane of Anzio, and they were stalled there in a deadly stalemate for about three months. Actually it was the bloodiest campaign for the Allies in Europe. Over 75,000 Allied casualties, British and Americans, suffered terribly. The Germans counterattacked several times trying to force the Allies back in to the Mediterranean. Came very close in February of 1944 to actually destroying the Allied bridgehead. In fact, it was Sparks’ division, in particular his regiment and his company, which stopped the fiercest German counterattack.

In that battle, which became known as The Battle of the Caves, Sparks’ unit was surrounded for about ten days, and as a company commander, he fought that battle very fiercely, and tragically, he was the only guy from his company … so here you have a 25 year old company commander, the only guy that survived the battle. He managed to get back to his own lines, but every other guy in his unit, in his company, D company, were either captured, wounded, or killed, which was a devastating blow to him as a guy that had loved every guy that he lead in that unit.

Brett McKay: How did he move on? He had to move on. They had to keep going, so what did-

Alex Kershaw: Yeah, I think one of the things that I found … I couldn’t understand. None of us can really understand is when you … number one, how you can last that long in that kind of combat. I’ve never been in combat, thank god. Number two, how you can then move on when you’ve felt so responsible for young men’s lives, and when you lose those men, when you lose all of your men that you’re in command of. I know that it didn’t break him entirely, but I know that for the rest of his life, he felt enormous survivors’ guilt. I think that his heart was definitely broken.

We know that we can … many of us can come back from a broken heart, it takes a long time, but the scars are always there. We all know that, that when you lose people you love, in many cases you can carry on, but you don’t really ever get over it. I don’t think Sparks ever got over that. I don’t think that he was the same person ever again. I think that was a deep, deep wound in him that lasted until his last days. I think that he … when I interviewed him, it was six months before he died, he was 89 years old, and he still felt those wounds very, very, very much. He felt an anger, and a heartbreak, and a deep, deep grief and loss. Over 70 years later, you can’t lose 200 young men that fought for you, that would die for you, and not feel anything but heartbreak.

Brett McKay: The amazing thing about Sparks, what impressed me, is he lead from the front.

Alex Kershaw: Yeah, absolutely.

Brett McKay: That was displayed … when they went to France, there was a battle at Reipertswiller? Ripes-

Alex Kershaw: Yeah, Reipertswiller, yeah.

Brett McKay: Where he displayed some heroics leading from the front, and even impressed an SS soldier.

Alex Kershaw: Yeah.

Brett McKay: Can you walk us a bit through that?

Alex Kershaw: Yeah, it was in Reipertswiller in the end of January 1945, just on the German border, and the Germans counterattacked … they counterattacked at the Battle of the Bulge in mid December. Then they had an operation called Northwind, which hardly anybody knows about, which is another attempt to push the Americans back at their borders. What you have to remember is when we invaded Italy, when we invaded France on D-Day, this is not German soil. And as I think everybody listening would recognize that if Americans are fighting in Mexico, they’re not going fight quite as hard as they would in Los Angeles, or Kentucky, or New York State.

When it’s your own country, it doesn’t matter … to some extent, it doesn’t matter who your leaders our, it’s your territory, it’s your soil, it’s your family that’s on the line here now. Point being, when we got to Germany, and when Sparks got to Germany, the Germans, and in his case, unfortunately the SS, who he respected enormously, they fought back viciously. In his battalion, he was a battalion commander, they were surrounded by the SS, being picked off methodically, very, very savage warfare, and Sparks wanted to try and rescue some of his men. He commandeered a Jeep, actually a tank, sorry, and he was seen by an SS machine gunner, a guy called Johann Voss, to jump off this tank and drag several of his wounded men on to the tank and then reversed down a mountain pass.

This is something that was unheard of. A battalion commander, a lieutenant colonel just to do things like this. It was a remarkable … and the SS guys that watched him do it, they wouldn’t hesitate to open fire most of the time, but this was so astonishing to them, to see an officer risking his life in such a way, to drag wounded guys to safety. But they didn’t open fire. They couldn’t kill him. It was something that was just a step too far. So yeah, that was an example of … it’s a perfect example … it was the main example of Sparks putting his life on the line … risking his life.

He snapped. He didn’t care any more. The only thing that mattered to him was to save some of his men’s lives. He’d lost a company at Anzio in February of 1944, this is almost a year later, and he was haunted by the lost. He said I didn’t care, I wouldn’t of cared less. All that mattered to me was that I would save some of my men. I wasn’t going to see all those guys be lost again. I wasn’t going to have that happen to me again without trying to do something about it. He should’ve been … some people said he should’ve been … he should’ve received the Medal of Honor. There was a campaign back in the … 15, 20 years ago to try and have him recognized and receive the Medal of Honor for what was an extraordinary act of courage and selflessness, and in tepidity, but he didn’t receive it, and he didn’t even receive the Distinguished Service Cross, which he was actually recommended for.

So yeah, he was an astonishing guy and the people that I had met that served under him … the veterans I met at reunions worshiped him. He was a god to them. He was someone that was a father figure. He was someone that … they knew the one thing that Sparks would do every day, and that’s what … and that would be to try and keep as many of them alive as possible. Sparks told me that his job was a terrible, terrible responsibility because every day he gave orders for his men to advance, well most days.

You have to remember the American Army was on the attack throughout the European campaign. They weren’t a defensive army, they were invading and the job of Americans in WWII in Europe was to land in Europe and get to Berlin as fast as possible. Then go to the Pacific and finish off the Japanese. It was just like every day, get up, attack, attack, attack, attack. You take a lot of casualties when you do that, and if you’re an officer, you’re asking your men to attack German positions over, and over, and over again. When you attack, you lose lives, and Sparks told me that his job was to get people killed every day. It was a good day if I got less guys killed than the day before.

So you have an idea of the responsibility there and every loss of a life effected him. But he cared about his men, and he cared about keeping as many of them alive as possible, and he thought it was his moral responsibility as a human being, not just as an officer, to actually if he was going to ask guys to get killed, and to fight for their country, and to lay down their lives, he should lead them whenever possible in those situations where they could be killed.

There were a couple of occasions when … I interviewed veterans and they said they were actually astonished that suddenly down the street, or out of nowhere, would come walking this Lieutenant Colonel right near the front lines, and sometimes at the front lines. They were astonished. They didn’t see anybody above a Captain anywhere near the real action for months on end. It was a joke among a lot of GIs that you never saw a senior field commander anywhere near the real shit. So excuse my language, but Sparks was there. He was there. That makes a massive difference. If someone is giving you orders, when you see the guy that’s giving you orders fighting beside you, taking the same risks, it is a very, very effective motivational tool, you know?

Brett McKay: So they advance from France in to Germany, and as you’ve said, they liberated the first concentration camp made in Germany, Dachau.

Alex Kershaw: Yeah. Yeah.

Brett McKay: What did the men think. I thought it was interesting how you did talk … they didn’t really know what it was when they first saw it, but how did they react once they realized what was going on there?

Alex Kershaw: Well it was a combination. I think that Sparks said to me, it seems that they encountered when they first entered the camp, where he said to me, beyond human comprehension, this is nothing they could ever prepare you for this. He said they had seen everything by then. They’d seen anything that you could possibly imagine as a combat infantryman. The worst of industrial warfare: civilians damaged, other men terribly damaged. Most Americans in the GIs, on the ground in combat in the European Theater, were killed by flying, hot shards of metal, pieces of shrapnel, particularly from artillery shells … mortars were also very effective.

You would often … when an artillery barrage occurred, it was probably the most lethal thing that could happen to you, and there were cases where you’d be right beside a really good buddy, and it was the buddy beside you that you always fought for, not … obviously people were very patriotic, they were fighting for the flag, they had a notion that they were fighting for civilization and to defeat barbarism essentially. But when it really came down to it, when you were really, really, when the S-H-I-T hit the fan, it was really the guy beside you that you fought for, and that guy fought for you, and your greatest fear was not so much the enemy, but it was letting the guy beside you down, of failing that person, that buddy, when both your lives were on the line.

There were cases I came across where you’d be beside that person you were fighting for, and then you would have pieces of that person splattered across you … across the stock of your M1 rifle and they’d be literally obliterated. So these were the things that really damaged people and that were almost daily occurrences. But even that didn’t compare to seeing thousands of people dead. Rotting corpses, and this is what greeted the Thunderbirds when they arrived at Dachau on the 29th of April 1945. The first thing they saw was what was called the Death Train. This was a train of wagons full of over 2,000 dead corpses. These were people that had been brought on the train for over two weeks from Kombuchenwald. They’d been starved. They hadn’t been given water, and then when they got to Dachau, some of them had crawled out .. miraculously some of them had survived, and some of them had crawled out, and then SS guards, as they crawled out of the train, had stomped on their heads.

They’d use the butts of their rifles to break their brains in. So these sort of things, when you saw this, and you had already been through … I think for some of these guys it was their 500th day of combat. So they were worn down. They were tired, they were brutalized, they were angry, they were on hair triggers anyway, ready to explode. When they saw this, many of them were absolutely enraged, and Sparks told me that he actually lost control of his men for a while. He couldn’t control them. He himself was lost for a while. He was in a daze, and he vomited, and he … it was something that was really, really beyond anything they could ever imagine.

Then you go through various stages of grief, of rage, of nausea, of being stunned, many guys were in tears. Then as they moved on in to the camp … they were on the outskirts, when they moved on in to the camp, there were 32,000 people in that concentration camp, Dachau, when it was liberated. First formed in 1933, for 12 years of death and people being worked to death, of evil, of decay, and monstrosity. And believe it or not, some people in that camp on the 29th of April 1945, had been there for over a decade. They’d been in Hell for that long.

So when they got towards the very center of the Dachau complex, there were 32,000 people there, over 50 nationalities: catholic priests, Jehovah’s witnesses, gays, mostly political prisoners. And when they heard the sound of combat, when they heard that Sparks and his men were there, and when they saw the green uniform of the American soldier, and they saw the helmets, and they saw the Thunderbird patch, etc, there was what Sparks told me, was like a chilling roar. 32,000 people roaring with pleasure and relief that finally their ordeal was over. In fact, many of the people that were saved by Americans there, they later on called the 29th of April 1945, the day upon which Americans liberated the longest standing center of evil within the Third Reich, the longest standing concentration camp, they called that day The Day of the Americans, because it was the Americans that had liberated them.

For some of them, it was literally the day the had been born again. They had though that their lives would be over, that they had really gone to hell, and then see the Americans give them a new chance at life, was something that was profoundly, profoundly effecting … incredibly moving. When we talk about cliches, such as the Greatest Generation … my son’s 19, I think that his generation is awesome too, every generation’s awesome. When you talk about Americans, working class Americans liberating Europe in WWII, you’re talking about an episode that is really sacrosanct, and beautiful, and pure. It’s an astonishing, astonishing achievement that Europeans will always be grateful for, the liberation of that beautiful, beautiful historic place, of that continent that gave birth to the Enlightenment, to the Renaissance, that produced American waves of immigration, that produced America, it’s an amazing thing that you had these young Americans going back to the Old World and liberating it, and liberating it from enormous evil, from enormous, unimaginable evil and barbarism. It’s a great … I think it’s the greatest achievement in American history. I think the few of those liberators that are still alive are the greatest Americans in American history.

The longer I spend in Europe, and I spend a long time in Europe taking Americans every year through the WWII museum, through tours I do with the museum, I go back for several weeks every year and take Americans to the places where Americans died to liberate that great continent. I’m increasingly … every day I do it, every year that passes when I’m in my 50s now, I am more and more at awe … in awe of that sacrifice and that heroism, and that courage. The effects of that, and the beauty of what was given to Europe and what was given to my generation of Europeans, it’s a truly awesome, awesome achievement.

Brett McKay: Well Alex, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about your work?

Alex Kershaw: You can go to my website: www.alexkershaw.com. I have my books listed there and I’m on Twitter, and Facebook, you name it. I love interacting with people, so please visit. Please visit me and hopefully enjoy, not just my stories, but other people’s stories too, because these … I was talking to a guy … I’ll shut up soon, but I was talking to a guy yesterday who told me that the American government has officially declared that the end of the practical lives, the lives that we can count on people still being … still having a heartbeat or WWII veterans is 2020. So we are now only two years away from the date that which the American government has decided that for all intents and purposes, the WWII generation will be no more. So we’re right at the end. We’re at that … as the sun comes down, that last glimmer of light on the horizon, that’s where we are in terms of these amazing people and I think it’s worth thinking about. It’s worth really thinking about that because when they’re gone, all we’ll have is archives and history books.

Brett McKay: Alex Kershaw, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Alex Kershaw: Thank you so much.

Brett McKay: My guest today is Alex Kershaw. He’s the author of several books on WWII. The book we discussed today was The Liberator. It’s available at amazon.com. You can find out more information about Alex’s work by going to his website: alexkershaw.com. Also, check out our show notes at aom.com/liberator, where you can find links to resources, where you can delve deeper in to this topic.

Well that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoy the podcast, or gotten something out of it, I’d appreciate it if you take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. Helps out a lot. If you’ve already done that, thank you. Share the podcast with your friends, that’s how we get the word out about this show. As always, thank you for your continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.