“Do you hear that? We’ll none of us get back to our homes again.”

Tom McLeod, member of the 1914 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, stood anxiously on the deck of the Endurance. He looked out on a nearby ice floe where ten Emperor penguins stood wailing a mournful cry. None of the ship’s twenty-eight member crew had seen such a large group of penguins gather together before, nor heard them issue such a strange and chilling sound. Surely, McLeod thought, this was a foreboding omen.

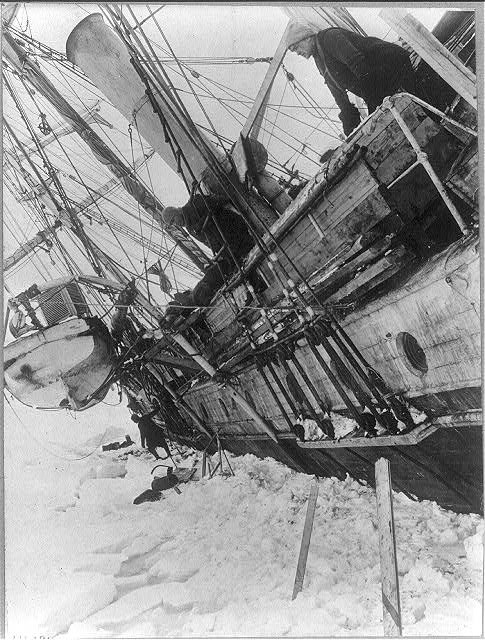

Ernest Shackleton, leader of the expedition, bit his lip. One did not have to be superstitious to feel the crew’s prospects were bleak. The Endurance had been stalled out for months, having become trapped in an ice pack as it sailed towards the South Pole. The crew’s aim was to launch an expedition that would traverse the Antarctic continent. But now the ice floes surrounding the ship had begun violently pinching and twisting it, tearing open holes in the hull through which freezing water poured. The men had worked for days in exhausting, round-the-clock shifts, pumping out the water by hand. But Shackleton knew their efforts were not enough to save the ship; the next day he ordered the Endurance abandoned. “She’s going boys,†he said. “I think it’s time to get off.â€

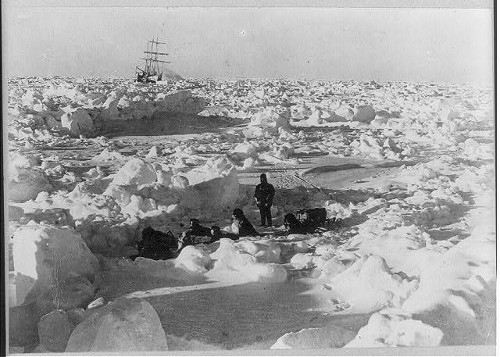

The men trudged out onto an ice floe, leaving behind what had been, all things considered, a warm and comfortable home. It was a farewell to their last tie to civilization. They had now entered a lone and dreary wilderness. The men set up their tents on a tenuous foundation that was likely no more than 6 feet deep and could crack open at any time – plunging them into the icy deep.

Shackleton strode from the Endurance carrying a copy of the Bible given him by Queen Alexandria at the outset of their journey and made his way to the center of the hastily constructed campsite. Gathering his men around him, he told them of the new plan: they would begin a march across the ice towards Paulet Island, some 346 miles to the west. As they hoped to hit open water along the way, the men would have to drag two, one-ton lifeboats along with them, hauling them across a vast wasteland of ice and over ridges that could rise two stories high. “We cannot hope to make rapid progress,†Shackleton told the men, “but each mile counts.”

Given the arduous nature of the task ahead, Shackleton solemnly informed his men that “nothing but the bare necessities are to be taken on the march, for we can not afford to cumber ourselves with unnecessary weight.†Author Alfred Lansing writes in Endurance that through studying the outcome of past expeditions, Shackleton had come to believe that traveling light was absolutely paramount, as “those that burdened themselves with equipment for every contingency had fared much worse than those that had sacrificed total preparedness for speed.”

Each member of the team was allowed the clothes on his back, plus two pairs of mittens, six pairs of socks, two pairs of boots, and a sleeping bag. Beyond these basic provisions, Shackleton ordered that each man only bring a maximum of two pounds of personal possessions.

Shackleton moved to set the example for his men. He took his Bible and ripped out the flyleaf upon which the Queen had inscribed: “May the Lord help you to do your duty & guide you through all the dangers of the land and sea. May you see the Works of the Lord & all His Wonders in the deep.” Then he tore out the 23rd Psalm, as well as a page from Job he considered “wonderfulâ€:

Out of whose womb came the ice?

And the hoary frost of Heaven, who hath gendered it?

The waters are hid as with a stone,

And the face of the deep is frozen. (Job 38:29-30)

Shackleton placed the torn pages inside his jacket and laid the Bible in the snow. He then reached into his pocket and withdrew a gold watch, gold cigarette case, and a handful of gold sovereigns. He gave the items one last look before tossing them into the snow as well.

It was a dramatic gesture, but Shackleton was determined to impress upon his men the absolute necessity of each man stripping himself of every ounce of superfluous weight. “No article has any value when measured against our survival,” Shackleton intoned. “Everything is replaceable except your lives.”

What They Left and What They Kept

Shackleton’s men were faced with a series of heart-wrenching choices. Given the scant two-pound allowance, which of their cherished personal possessions should they keep, and which should they cast aside into what Shackleton called “the privacy of these white graves�

Taking inventory of what the members of the Endurance expedition decided to keep and what they left behind can teach us much about what is truly valuable — not only literally, in terms of material possessions — but as broader symbols of what matters most in life for all of us.

We may never face a situation of life and death survival as the members of the Endurance expedition did. Yet in a world of gray morality, shallow culture, and relentless consumerism, the survival of every man’s values, happiness, goals, and manhood are ever at risk. Every “mile†matters in our personal journeys too, and the lighter we travel, the further we can get in the goal of becoming men of excellence. What kinds of things should we “carry†with us on life’s journey, and what weighs us down and keeps us from ever getting where we want to go?

What They Left Behind

Money/Jewelry/Gold. The thing that had the most value in the explorer’s lives back home would have the least value on their Antarctic march. Or as Frank Worsley, captain of the Endurance put it, “there are times when gold can be a liability rather than an asset.†Heavy and worthless, their “wealth†would simply serve to weigh them down.

- As a symbol for our own lives: Few things can impede your search for a happy and fulfilling life more than a love of money and a heedless pursuit of material possessions. Debt shackles. Accumulating piles of shiny tchotchkes doesn’t bring lasting satisfaction and forces you to invest your time in taking care of your stuff, rather than in things with true value like relationships, experiences, and service to others.

Clothes. The men could only take the clothes on their backs. Their remaining pairs of pants and shirts were jettisoned.

- As a symbol for our own lives: This one can translate more literally and relates to the point above. Instead of having a huge wardrobe, just have a few pieces that really get the job done and will work in a wide variety of situations. Instead of having a house full of junk, try to own only those things you really need, use, and get true enjoyment from.

Scientific instruments. In addition to the goal of being the first men to cross Antarctica, the expedition had also originally aimed to gather geologic and other scientific data about the continent. But with the sinking of the Endurance, that original purpose had to be jettisoned; the men had to focus all of their energies on their new mission: simply making it home alive. Thus, microscopes, telescopes, and other scientific equipment were discarded in the snow.

- As a symbol for our own lives: Sometimes the plan we set out for ourselves – either professionally or personally — changes dramatically. These curveballs can come because of an intentional shift in our goals, or from challenges and circumstances over which we have no control. Either way, there’s no use in holding onto the past. You have to leave behind the trappings and the baggage of your old dream, and ditch the regrets for what could have been and the guilt for the path you “should†have taken. When plans change, one must find a new purpose, and press onward.

Books. Reading had been a welcome source of entertainment for the men while they lived on the Endurance. But given their size and weight, there was no way the books could be bought along on the march.

- As a symbol for our own lives: Studying and educating ourselves about who we want to be and how best to do something is absolutely vital. But there also comes a time when you have to move beyond the realm of the abstract and hypothetical, get moving, and try to do the thing yourself.

Suitcases. The men did not simply leave their suitcases behind, but instead used the leather from them to make something that was badly needed: new boots.

- As a symbol for our own lives: I love this one, because the men took the thing that holds all the stuff you tote along for a trip, and transformed it into something to sheath the only true essential you need for a journey: your own two feet. It captures the essence of traveling light. In all areas of our lives, from paring down how much stuff we own, to peeling back the influence of media and popular culture in order to find our own beliefs, to homing in on our life’s purpose, we are well-served in stripping away the dross in search of the essential core.

What They Kept

Toothbrush. When it came to cleanliness on the expedition, Lansing describes the men as divided into two camps: “some men scrubbed their faces in snow whenever the weather permitted. Others purposely let the dirt accumulate on the theory that it would toughen their skin against frostbite.†But there was a general consensus when it came to the importance of caring for one’s teeth, and thus most of the men chose a toothbrush as one of the few precious items to bring with them. Thousands of miles from the nearest dentist, a painful problem with one’s teeth could have spelled real trouble on the march.

- As a symbol for our own lives: As you can see, the idea that daily tooth brushing is one of the habits every young man should develop is endorsed by Arctic explorers! But one can find a deeper meaning here beyond the necessity of keeping your chompers in good condition. There are many things in our life that require mundane daily maintenance to keep on top of, and while consistency in these small, regular efforts may not be fun, they ultimately prevent the creation of huge problems and pain down the line.

Religious items. Many of the men kept small reminders of their faith. Shackleton had his few pages of the Bible. Tom Crean kept a devotional scapular that he had worn around his neck since he was a young man. Such tokens offered strength and comfort to the men in incredibly trying circumstances, while also reminding them of their families and their roots as well.

- As a symbol for our own lives: Faith, spirituality, and philosophy can offer meaning and purpose beyond ourselves and help us continue on when we face challenges and struggles. Our beliefs provide direction as to the big questions of who we are, why we are here, and where we are going, and moral reminders are key in helping us remember those answers.

Photographs. The most universal item the men chose to take with them were a few photographs of loved ones back home. Completely isolated at the bottom of the world and faced with traversing an alien terrain, they felt a million miles from their old lives. Photographs kept their connection to home alive and reminded them that there was something worth fighting to return to.

- As a symbol for our own lives: Our relationships are truly the most valuable things in our lives. Connections with friends and family have been proven by science time and again to be the single biggest contributor to happiness. At the end of their lives, it’s their relationships that people look back on most fondly and regret not investing more time into. Our loved ones not only bring us joy and add a beautiful depth and richness to our lives, but also give us something to live for.

For some members of the expedition, the two-pound weight limit was relaxed to allow them to carry items with a value that was deemed worth the extra burden.

Medical supplies and instruments. The two surgeons amongst the crew were allowed to bring their first aid supplies and medical instruments; it didn’t matter how light the men were traveling if an injury or ailment kept them from moving at all.

- As a symbol for our lives: Is there anything more valuable than our health? Good health must form the foundation of our lives, as achieving all our other aims becomes much harder, and sometimes impossible, if we are extremely obese, very sick, or quite dead.

Banjo. Leonard Hussey’s five-string banjo weighed 12 pounds – making it practically an anvil compared with each man’s Spartan allotment. But Shackleton insisted it be lashed underneath one of the lifeboats and brought along. “It’s vital mental medicine,†he said, “and we shall need it.†He was right. At the end of their grueling journey, Shackleton credited the banjo’s music and the crew’s frequent sing-alongs “to being a vital factor in chasing away symptoms of depression.â€

- As a symbol for our lives: Oftentimes when we’re trying to turn our lives around, we concentrate on getting rid of what’s not working: throwing out our junk, ending toxic relationships, quitting bad habits. But becoming the man you want to be can never be entirely about emptying yourself of the bad; you must also fill the newly created space with the good. We need people/hobbies/traditions in our lives that brighten the way and bring us joy and fulfillment.

Diaries. The men who kept diaries were allowed to bring them along. These journals later proved invaluable in the ability of Shackleton and future authors and historians to create and share with the world a richly detailed account of the expedition, ensuring that this epic story of survival, courage, and leadership would not be forgotten.

- As a symbol for our own lives: In a literal way, keeping a journal offers numerous benefits. In a symbolic way, understanding our personal histories, whether written down or simply etched in our brains, is essential to making progress in our lives. What experiences made us who we are today? What dreams and ideals from our youth do we want to carry into our manhood? What mistakes did we make in the past that we don’t want to repeat?

Conclusion

If you were faced with the same kind of decision as the members of the Endurance crew, which of your personal possessions would you take and which would leave behind? What does the nature of your selections reveal about what you truly value in your life?

On a deeper level, what attitudes and behaviors are you carrying with you that are actually weighing down your progress on your own 20 Mile March? What negative habits have become a burden, keeping you from becoming the man you want to be?

Once you answer such questions, the most important question then becomes: are you putting your time and money where you mouth is? Are you investing the resources of your life into what you truly value, or are you wasting them on things, that, if push came to shove, you would ultimately leave behind in an icy grave?

_________________

Sources:

Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing

South: The Story of Shakleton’s 1914-1917 Expedition by Ernest Shackleton

Tom Crean: Unsung Hero of the Scott and Shackleton Antarctic Expeditions by Michael Smith