John Henry was born with a hammer in his hand. The unusually large and strapping baby grew up to be an unusually large and powerful man; 7 feet tall, his arms were as thick as tree trunks and his shoulders were so wide he had to walk sideways through doors.

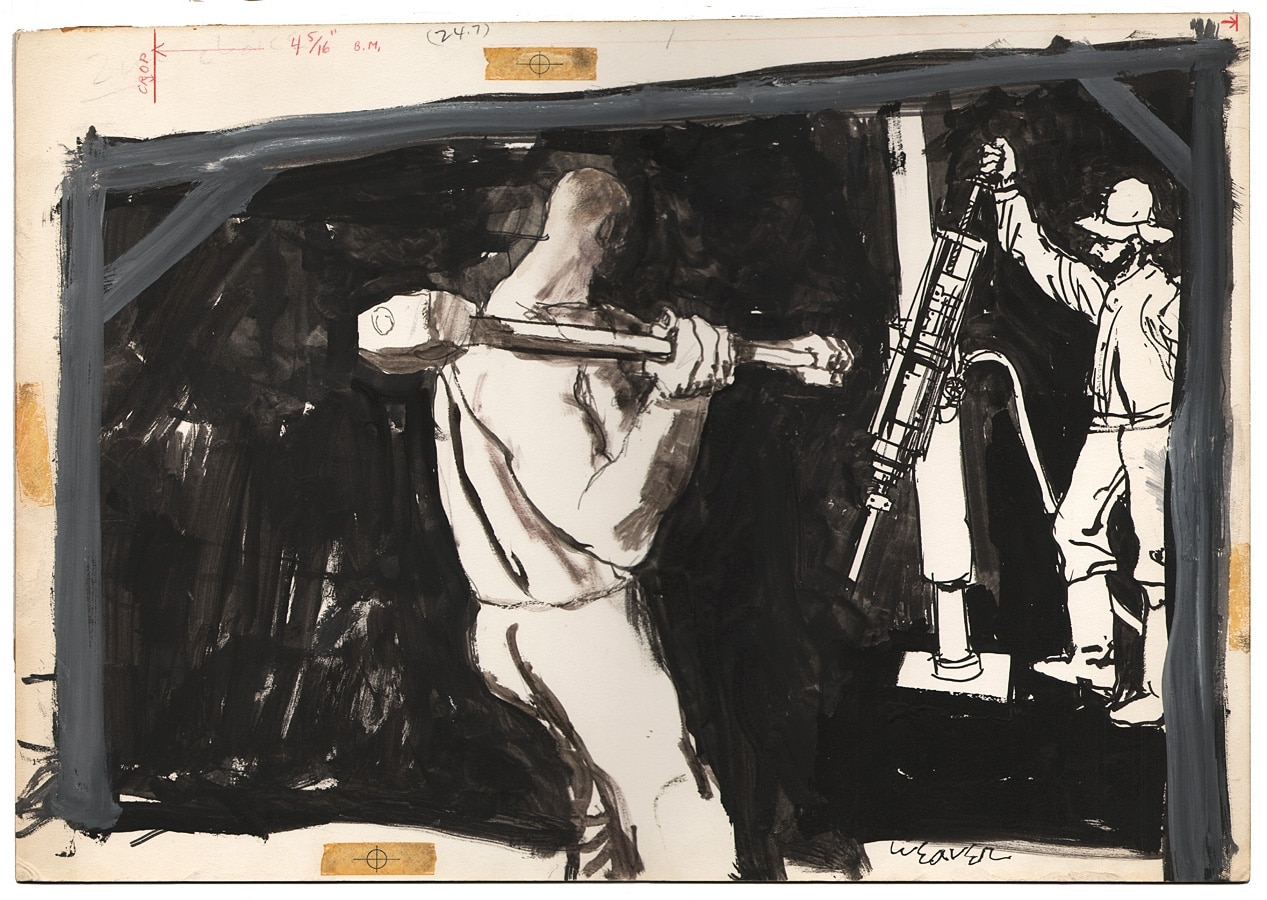

After being freed from slavery, Henry began to work for the railroads, joining a tunnel-making gang in the Allegheny Mountains of West Virginia. As a steel-driving man, he hammered spikes into the thick rock that stood in the way of soon-to-be-laid track, drilling holes that were then filled with dynamite and blasted open. Henry’s strength and stamina in this arduous work surpassed that of any other man; hour after hour, Henry would swing his hammer like lightning and make the steel sing so loud it could be heard hundreds of miles away.

One day, a salesman approached the railroad boss pitching the purchase of a new steam drill he claimed could do the work of ten men. Unlike living men who have to eat and rest, the salesman crowed, the inanimate drill could run nearly non-stop.

Henry immediately understood what the coming of this machine would mean for he and his fellow laborers; they would all soon be out of work, their flesh and blood replaced by gears and grease. The drill would deprive them of a livelihood and the dignity that went with it. Henry couldn’t let that happen.

Believing his manpower was even stronger than the drill’s steam-power, he challenged the machine to a race. If he lost, his boss agreed to buy the machine. If he won, Henry and his gang would keep their jobs.

A huge crowd gathered to watch the contest. The city folk were certain that machines represented the future, and that Henry had no chance. The local men, who’d seen Henry’s strength up close, put their money on the steel driver to come out on top.

At first, the steam drill surged into the lead, but Henry put another giant hammer into his other hand, and soon began wailing at the steel with both arms, enabling him to pull ahead. Henry pounded the steel until his hammer burned white hot, and had to be dipped into a bucket of water to cool. Whenever his body grew weary, he’d shout, “A man ain’t nothing but a man. Before I’ll be beat by that big steam drill, I’ll die with my hammer in my hand!” And on he’d soldier.

After nine hours, the holes the man and the machine had each respectively made were counted up, and Henry, who had made more, was declared the winner.

Victory for the steel driver was short lived, however. Clutching his chest, Henry collapsed, and died with his fingers still wrapped around the handle of his hammer. His heart had been big enough to conquer the challenge, but ultimately too small to outlast the machine.

A handful of steam drills soon replaced hundreds of steel-driving men, who scattered across the country, trying to make a living by cobbling together whatever kinds of work they could find.

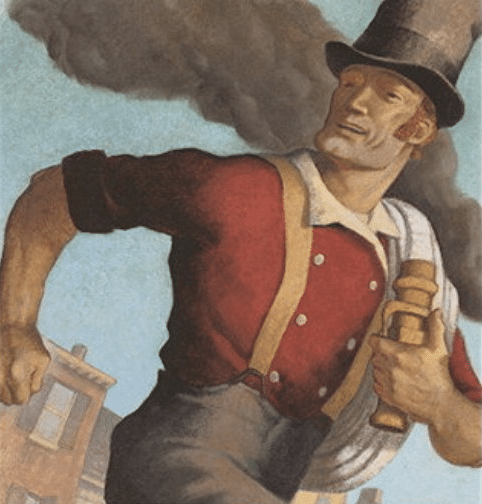

Paul Bunyan was a most unusual baby. He was unusually large and unusually hungry — his parents had to milk two dozen cows to keep his bottles filled and spoon-feed him barrels full of cornmeal mush — and his face sported a most unusual feature for an infant: a full, bushy beard.

This unusual boy grew up to be a one-of-a-kind man: seven feet tall with a seven-foot-long stride, Bunyan’s laugh could shake branches off trees and his pipe was so big its tobacco had to be packed in with a shovel. Raised in the backwoods of Maine, he learned early on how to hunt, fish, and fend for himself, and developed unrivaled strength and skill.

When he came of age, Bunyan struck out on his own and headed west to become a logger. Along the way he found a companion that could match his brawny stature: a giant blue ox. Babe weighed five thousand pounds and could work with the strength of ten horses. Babe could pull a crooked river straight and break up logjams by swishing his tail in the water.

With his trusty, oversized ax, and his trusty, oversized ox, the giant lumberjack could fell a dozen trees with a single swing, and found so much success in the logging industry he started his own camp. And what a camp it was! Its dimensions were as outsized as its proprietor. The bunkhouses were a mile long, with bunk beds stacked ten high.

The camp’s cook fried up flapjacks on a 40-acre long stove that was heated by creating a forest fire beneath it. The griddle’s surface was greased by a dozen men who wore huge slabs of ham on their feet and skated around its surface, and the pancake batter was created in a kind of giant cement mixer, and then sprayed on the griddle from a hose. The grub that emanated from this massive kitchen was eaten on an equally massive table – one so long it took a week to pass the salt to the other end.

Bunyan and his crack team of lumberjacks were so efficient at clearing timber, they managed to harvest one hundred million feet of pine from just 40 acres of land.

Good as they were at their job, however, a salesman arrived in the camp claiming he had a machine that could do it much better. He explained to the loggers the way in which the new steam-powered saw he demonstrated could fell trees far faster than any axe, even one wielded by a man as strong as Paul Bunyan. So too, the salesman claimed, the new steam engine railroad being built nearby would be able to haul the timber away faster than any animal, even an ox as mighty as Babe.

Incredulous, Bunyan challenged the machine to a tree felling contest.

For an hour, the steam saw tore through tree after tree, while Bunyan seemed to hew down just as many with his simple steel blade. Babe and the train engine raced to pull the freshly-cut timber into piles. When time was up, the respective stacks of resulting timber were measured, and the outcome solemnly announced: the steam saw had won . . . by just a quarter of an inch.

With Bunyan’s and Babe’s brawn no longer needed, the pair made their way up to Alaska, where there was still plenty of room to roam, and still plenty of tasks that called for their epic strength and hands-on skill.

Mose Humphrey isn’t as well-known as Bunyan and Henry, perhaps because he lived out his exploits in the city, rather than on the frontier. But he was a character just as legendary.

“Big Mose” lived in the rough and tumble Bowery area of New York City, with a physique that matched his nickname, and a demeanor suitable to the neighborhood.

Eight feet tall with hands the size of cast-iron skillets and a big granite-like chin, the red-headed Mose was said to have the strength of ten men and was known as “the toughest man in the nation’s toughest city.” He could swim across the Hudson River in two strokes, and all the way around the island of Manhattan in six. He puffed on a cigar two-feet long and exhaled the smoke so forcefully that it pushed sailboats in the harbor off course.

Mose thus cut an intimidating figure as the leader of the Bowery Boys gang. In taking on rival gangs from the Five Points, like the Dead Rabbits, Mose would hoist and lob giant paving stones and uproot lampposts and trees, wielding them like other men would a baseball bat.

Despite his rough exterior, however, Mose really had a heart of gold. A regular parishioner at St. Andrew’s Church and a dedicated husband, he was in fact best known not for his fighting prowess, but as the city’s best and bravest firefighter.

Firefighting in the mid-19th century was an all-volunteer affair, and the job not only required even more speed, strength, and stamina than it does today, but simply more bodies as well.

Heavy fire “engines” were propelled neither by horse nor motor, and instead were pulled through the streets of NYC by sheer manpower alone. Once the wagon arrived on the scene, its hoses were attached either to the city’s few hydrants or dropped directly into a body of water. The “fireboys” then had to work a manual pump to generate enough pressure to propel the water through the hoses and onto the flames. Pushing the wagon and manning the pump could require up to 30 men.

Firefighting was also a competitive enterprise. 4,000 volunteers were organized into hundreds of rival companies in the city, all of which sought to be the first to arrive at the fire, seize an available hydrant, and put out the blaze. Jockeying for position sometimes beget out-and-out fist fights between the companies, who simultaneously fought each other, and the fire.

In both battles, Company 40 had a huge advantage in being captained by “Mose the Fireboy.” He could easily drag the company’s “pumper” for miles by its rope, had an uncanny ability to walk through flames unscathed, and possessed the strength to remove any obstacle. Once, for example, a trolley card became stuck on its track and blocked the path of Company 40’s pumper. Old Mose just lifted it up, hoisted it above his head, and put it down out of the way. Another time, Mose made a tunnel to New Jersey to siphon enough water from the Hudson River to put out a huge fire in the city. And he always managed to rescue would-be victims of blazes — including all the children in an orphanage fire — even if it meant putting himself in considerable danger. When citizens thanked him for his heroism, he’d always reply, “I’m just doing my job.”

One day, however, he realized his services were no longer needed. Responding to the alarm bells signifying a fire down by the docks, he dragged the pumper through the city’s streets, only to arrive to find streams of water already dousing the flames. The water was being pumped from a horse-drawn, steam-powered engine, a powerful pumper that only required six men to operate, instead of the two dozen who typically worked alongside Mose. And these firefighters weren’t volunteers, but trained, paid professionals.

Mose could see that the era in which every man could pitch in in an emergency, and epic strength was a valuable asset, had come to a close. He sadly pushed his company’s old pumper off the dock, and disappeared into the large crowd who had gathered to watch the professionals do their work.

Mose vanished from his old Bowery haunts after that day. Some said he had gone to California to mine for gold; others said he had joined the Pony Express.

But according to one storyteller, an old veteran from the days of volunteer fireboys swore he’d seen Mose around the city:

“If you want to know the truth about Mose, pay attention to me. He’s among us still. I seen him hanging around lampposts on cold winter nights. I seen him sleeping in burned-out old tenements. I seen him walking along foggy wharfs.

You could say old Mose is the spirit of New York. And when all them shiny new machines decide to break down, and when the city fire-alarm bell starts to ring again, watch out. Because by then, you know, that fireman will have grown to be at least twenty feet tall.”

The Tragic, Liberating Message About Manliness Hidden in American Tall Tales

“The opposite of manliness isn’t cowardice; it’s technology.†—Nassim Taleb

You probably hazily remember tall tales, like the ones we’ve re-told above, from your childhood. When you were a boy, what likely stood out to you about these exaggerated folk stories (which were often at least tangentially inspired by real-life figures) was the humor in the outlandish plots, and the heroism evinced by the protagonists. The characters of tall tales are larger-than-life: taller, stronger, and cleverer than the average person.

In recently re-reading a collection of tall tales as a grown man, however, I noticed something else in the stories as well. Something darker, more tragic.

Several tall tales, I observed, share a common theme: a big, brawny, good-hearted man makes himself useful to others through his physical strength and skill, only to be replaced and rendered irrelevant by an advancement in technology. He’s pushed aside, consigned to find a place that’s less civilized, where the traits of manhood are still needed — or into the grave itself.

The irony is that the masculine traits that allow these characters to tame the frontier, battle nature’s elements, and tackle arduous tasks, are the very same ones that create the men’s ultimate obsolescence. Boldness, ingenuity, stamina, and courage can be used to grapple with the physical world . . . but they can also be harnessed for the task of innovation. Manhood, in this more abstracted form, creates the technology that diminishes the need for manhood in its most concrete, fundamental form.

In other words, manliness kills manliness.

That’s a kind of tragic reality, but understanding it is also sort of liberating.

The Obsolescence of Men and the Rise of Tall Tales

As we’ve discussed before, our modern cultural “manhood crisis†is nothing new. Such periods crop up repeatedly, generally when an industrial revolution (there have arguably been four), is coupled with a period of peace.

Machines negate the need for men’s physical strength, aggression, and grit, and there are no battlefields on which they can otherwise prove their courage. There is no existential threat that calls upon particularly masculine qualities to tackle.

In such times of technological ease and comfort, after men have tamed the wild and quieted the violence of crisis and paved the way for civilization to grow apace, society has the luxury of blurring gender roles; each sex is about as equally well suited for every task as the other. The whole concept of manhood seems obsolete.

The last time we had one of these periods was around the turn of the 20th century. Technology grew stronger and the memory of the last bloody crisis — the Civil War — grew fainter. What would become of men, people wondered, when instead of hunting game, pioneering land, and fighting wars, they instead sat all day at white collar jobs?

This was the same time, not so coincidentally, that the popularity of tall tales flourished. Men knew what ailed them, and that their own sex had in fact created the problem. And the difficulty of the situation was that while the manly traits of boldness and mastery lived on in the fields of technology and science, they became the purview of a smaller and smaller number of men; innovators continued to explore frontiers — more abstracted frontiers, but frontiers nonetheless — but few men were going to be able to make their living in labs. What then was going to become of the mass of men?

Given this worry, tall tales are unsurprisingly tinged with a nostalgic celebration of what was and an air of tragedy about the future. Despite their outsized manliness, the stories’ heroes are still outmatched by forces beyond their control. They thus choose to go their own way, in search of wilder pastures where the march of technology has not yet intruded.

Defeated resignation was certainly not the only response generated during this period, however.

While some men gave up on the idea of living a manly life in a time of peace and prosperity, others realized that even though challenges were no longer inherent in the environment, and no longer forced upon them by circumstances, they could still seek out hard things themselves.

These men gave birth to what is now called “The Strenuous Age.†They pushed themselves to stay fit and active, to learn and maintain hands-on skills, and to live with big hearts, not because they had to, but because they wanted to.

They decided there was still an opportunity to embody the kind of heroism evinced in tall tales, even outside the frontier, and even outside laboratories — that they could live with bravery, boldness, and virtue, and be larger than life, even within the small spaces of their everyday existence.

The Liberation of Understanding What Kills Manliness

The men of the first Strenuous Age knew what had enervated manhood, and thus knew how to counteract it. They started gyms, and scouting troops, and fraternities, and pursued hobbies that allowed them to exercise manual skills — they came up with intentional ways to re-embrace the tangible world and scratch their masculine itch in a time when it might otherwise go untouched.

Even though we live in a similar time, modern men are disadvantaged in that they often don’t understand what’s the matter with men today; they don’t know why they feel such a shiftless malaise. They look for someone or something to blame — often women in general, and feminism in particular, not understanding that the latter is not the direct cause, but rather a natural byproduct of what is: technology.

Technology is a wonderful thing, and almost no one wants to do without it. But it’s also dissolved millions of jobs, especially those that call for manual skill and strength. The percentage of men participating in the workforce has dropped in recent decades and continues to fall; 1 in 6 men in their prime working years is not employed, and isn’t looking for work either. They’ve given up and dropped out, and 10 million men that economists would otherwise expect to be employed, have gone missing from the workforce.

Technology has led to men feeling less needed and less necessary, and expiring not from overwork with a hammer, but an overdose from opiates.

This is indeed tragic, and men deserve far more sympathy than they usually get.

But knowing why something is happening, even if it doesn’t immediately solve the problem, at least offers a certain kind of relief.

Knowing that it’s simply manliness that kills manliness (men have filed over 80% of patents) allows you to make sense of the muddle and confusing reality of the modern world.

You can direct your energy away from feeling diffuse anger and anxiety, and turn your attention to what you can work on. It’s liberating to understand the cause of something. Because once you do, you can start working on the antidote.

For modern men, that means striving to bring about a New Strenuous Age. Embodying manhood and striving for heroism where it’s still possible.

When I interviewed Tim Whitmire and David Redding, the founders of F3, for the AoM podcast, they argued that the reason many modern men feel lost is that they feel adrift in the absence of an existential threat. They long to be heroic in the traditional way — being courageous in war or some other kind of crisis. Denied this opportunity, they retreat into a fantasy world, where they imagine themselves as the hero of the modern tall tale — a Jack Reacher-type character, who wanders the world without any responsibilities, sleeping with beautiful women, and repeatedly saving the day.

What men need to do instead, Whitmire and Redding said, is to see that there’s heroism in leading their families, in mentoring people in the community, in being a loyal friend, and finding a higher purpose — of any kind — in their lives. This is the kind of manhood that is needed in every age, in every place.

Maybe that seems too trite to be true, too naive to work, but think about a man like Theodore Roosevelt. Even though he could have led a very posh, comfortable existence, through sheer will he created a life that was arguably just as unbelievably epic as the character of any tall tale. His life wasn’t any less remarkable for having been lived out during a period of luxury and convenience; on the contrary, the fact he lived with such purpose despite having the option to choose an easier way, makes his efforts all the more laudable.

Making an effort like that, even if you never quite reach Bull Moose levels, is certainly more admirable than choosing to not even try, and escaping the vapid weightlessness of modern life by spending every night couch surfing and watching Netflix, dreaming of apocalyptic scenarios that likely will never happen, and if they did, you wouldn’t at all be prepared to face.

Because the funny thing about the way manliness kills manliness, is that once technology makes things safe and comfortable, it also seems to make men bored, so that, on a subconscious level, they seem to always end up sabotaging this pax romana, and precipitating yet another crisis, where the more visceral forms of manhood are again needed.

As the old “fireboy†put it, just wait until the machines break down, then you’ll see old Mose, and many other men, step up again.

But men don’t have to be ghosts in the interim. They don’t have to disappear, or move to Alaska. They needn’t swing giant hammers or axes to walk tall, to live larger-than-life, to become legends in their families and communities.