Jack London followed up the resounding success of The Call of the Wild with two more popular novels: The Sea-Wolf and White Fang. He continued to publish numerous short stories, articles, essays, and poems in magazines across the country as well. Now thirty years old, he was the highest paid writer in the country and a national celebrity. All the rich and famous, the movers and shakers, wanted to meet him, to dine with him, to have him attend their parties.

As Jack rubbed shoulders with society’s upper crust – ladies and gentlemen who would not have even looked in his direction just a few years before — he expected to feel elation. Everything he had worked for was finally his. Yet what he experienced instead was utter emptiness. He looked around and saw only “sycophants, well-dressed, well-mannered and glib.†He had thought that rising to the top of his profession would fulfill that aching for greatness that had been urging him on since boyhood. But he realized, with a rising sense of panic, that fame and recognition did not satisfy:

“The things I had fought for and burned my midnight oil for had failed me. Success — I despised it. Recognition — I was appalled by their unlovely mental mediocrity. Love of woman — it was like all the rest. Money — I could only sleep in one bed at a time, and of what worth an income of a hundred porterhouses a day when I could eat only one?â€

Jack London had come to a realization experienced by many who spend years focusing all their energies on a singular goal: the climb can be far more satisfying than the summit itself. Astronauts and Olympic athletes often become depressed after they return from space or win a medal. After devoting years of their life to reaching that achievement, they are then faced with a new challenge: navigating a featureless landscape and the yawning question of “What now?†So it was with London. He fell into a dark depression, which he termed his “Long Sickness.†For the first time in this vital man’s life, the world felt repulsively hollow. And while his thoughts did not turn to John Barleycorn as a solution to his gnawing emptiness during this time, he obsessed about something far more serious: “my revolver, the crashing eternal darkness of a bullet.â€

Four things would ultimately pull Jack out of his Long Sickness: his passion for Socialism, the land, physical exercise, and his soulmate.

Recovering from the Long Sickness

Of the all the ideals Jack had once held in his youth, only his socialist political views continued to burn within him:

“It can be seen how very sick I was. I was born a fighter. The things I had fought for had proved not worth the fight. Remained the People. My fight was finished, yet something was left still to fight for—the People…the People saved me. By the People was I handcuffed to life. There was still one fight left in me, and here was the thing for which to fight.â€

Jack threw himself with “fiercer zeal into the fight for socialism,†passionately stumping for it in speeches and in his writing. Although his publishers warned him that his rhetoric was a turn-off to a large segment of the population, and would cost him a good deal of money (perhaps in the hundreds of thousands of dollars), Jack persisted in crusading for his beloved cause. Doing so helped him maintain a sense of purpose and provided an outlet with which to keep the embers of his thumos smoldering.

Even more beneficial, however, was finding the next great challenge of his life: ranching. Thumos is not designed to run full throttle day in and day out, but rather to gallop along steadily, waiting to be called up to full service in certain seasons when all of its energy, fight, and drive are needed. To recover from such taxing seasons, men throughout history have found it wise to give their thumos some pasturage – quite literally — by turning to the land and to nature. Think of Cincinnatus returning to the plow he had left behind after being summoned from his farm to don his senatorial toga and then successfully leading the Romans in battle. Or George Washington’s desire to leave public life behind and retire to Mount Vernon after commanding the Continental Army. Even modern day soldiers have found nature to be an effective curative in healing the trauma of war. Working the land can be restorative for a man’s spirit, while at the same time offering him the challenge of pitting himself against the elements of nature. It allows him to exercise his thumos, but to do so in a steady, calming way that doesn’t exhaust it in the same way that human battles do, and brings satisfactions different than the honor and awards of the civilized world.

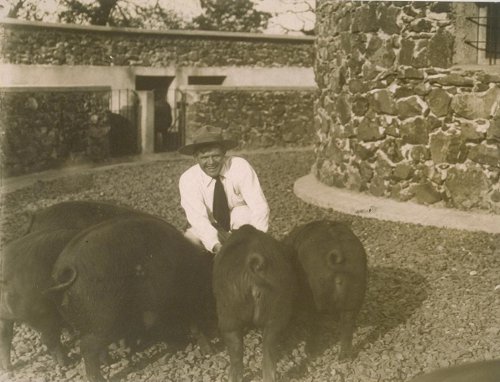

Jack and his pigs at Beauty Ranch.

London had been relentlessly driving the white horse of his thumos towards success for nearly a decade. It was tired and so was he. He was also drained by the strain of being in the public eye and dealing with the constant criticism of his work and personal life. He “grew tired of cities and people†and being surrounded by what increasingly felt like the grating superficialities of modern life. Jack called the city a “man trap,” and all he wanted “was a quiet place in the country to write and loaf in and get out of Nature that something which we all need, only the most of us don’t know it.†So in 1903 Jack bought 1,000 acres of land in Sonoma Valley – his Beauty Ranch. As Charmian put it, because of his “disheartenment with human beings, both in the mass and as individuals in the main, he turned to the soil to save himself.” London intended to create a true working ranch and successful business enterprise. He planned for stands of eucalyptus trees, a giant barn, a blacksmith shop, two grain silos, and a pig enclosure for herds of swine. As his biographer put it, Jack was “always at his best when setting himself seemingly impossible tasks,†and “he threw himself body and soul at this new challenge.” “I am trying to master this soil and the crops and animals that spring from it,†Jack said himself, “as I strove to master the sea, the men, and women, and the books, and all the face of life that I could stamp with my ‘will to do.'”

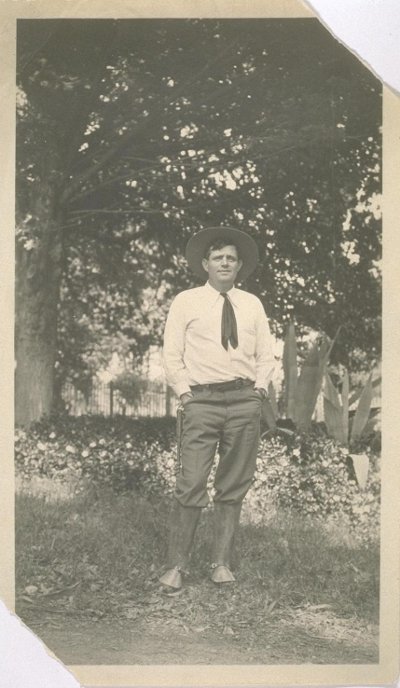

Jack looks over the Valley of the Moon at his ranch in Glen Ellen, California.

In addition to the exercise he got managing his ranch, London also found that bouts of purposeful physical activity of all sorts lifted his spirits greatly. He took joy in riding horseback over his land, hiking over its hills, and swimming in its watering holes. He boxed, and fenced, and shot guns. He practiced diving — working on his forward and backwards somersaults, walked on his hands to strengthen his arm muscles, and rode his bike out into the countryside. With his good friends, he tramped through the woods, roughhoused, and flew kites. At night they would sit around the campfire reading and talking, and would then fall asleep under the stars. He bought a stout sloop, The Spray, and would spend weeks living aboard the boat and sailing around the bay. Jack wrote to a friend about his new regimen: “It is Voltaire, I believe, who said: ‘The body of an athlete and the soul of a sage; that is happiness.’â€

If fighting for socialism, working the land, and getting out and exercising, began his “convalescence†from depression, it took “the love of woman to complete the cure and lull my pessimism asleep for many a long day.â€

The Final Piece to His Happiness: Jacks Meets His Mate-Woman

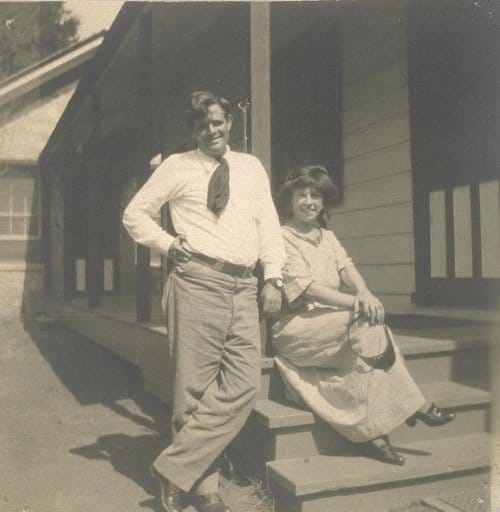

Jack and Charmian

Jack believed that were two types of females: Mother-Woman and Mate-Woman. The former was pure, sweet, and domestic – well-suited to raising children. The latter was strong, clever, lusty, and full of life – the kind of woman London could see partnering up with primal man in the primitive days of yore.

Jack’s first wife was a Mother-Woman. When he was 24 and his writing career was just beginning to take off, he tied the knot with Bess Maddern. When it comes to successfully guiding the chariot of one’s soul, the charioteer should let reason guide his thumos, which is the seat of love and emotion. But reason shouldn’t entirely usurp the role of the white horse. Young Jack had gotten the idea into his head that love was too unstable an emotion on which to build a marriage, and that a man should take a wife on purely rational grounds. He felt the restraint of marriage would add further steadiness to the life of discipline he was creating for himself at the time and would make him a more “wholesome†man. Jack did not love Bess, and she did not love him, and both openly acknowledged that fact. They liked each other well enough, he thought Bess would be a good mother, and he figured those two things would form a sufficient enough foundation for a lifetime of marital happiness.

Jack and Bess conceived two daughters together but it did not take long for London to realize he had made a big mistake. She was indeed the doting mother he had imagined, but she had no time or interest in anything outside of their children – Jack’s ideas, hobbies, friends, and, most dishearteningly, his sexual advances. Jack was a highly virile man who had enjoyed many a fling in his youth and scoffed at what he felt were society’s overly prudish views of sex. But Bess was not interested in sexual exploration or even basic intercourse, which even within the bounds of marriage she saw as debase. Sex was thus a rarity for the couple. Jack described Bess to friends as “a gossip, mean-spirited, and cold as the Klondike,†and felt as though he were suffocating in the relationship.

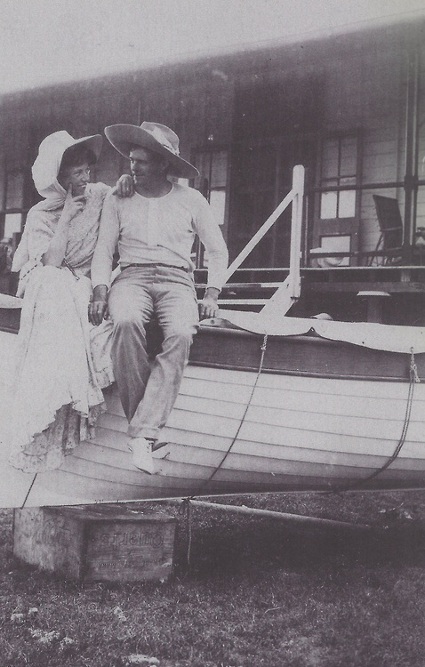

Jack and Charmian sit on the yacht they were building in hopes of sailing it around the world.

As Jack’s marriage to Bess dissolved, he met his perfect match, his Mate-Woman: Charmian Kittredge. Charmian worked independently as a stenographer, and was everything Bessie, and most other women of the day, was not. Her contemporaries described her as unattractive, but Jack was smitten with this woman who was able to keep up with his need for physical and intellectual stimulation. Charmian was sexually uninhibited, far from demure, and would not get hysterical when things took a turn for the dangerous or the simply annoying. As such, she made the perfect travel partner and adventure companion. She sailed, hiked, rode horses, and even boxed with Jack throughout their marriage. She was well-read and well-educated and became his helpmate professionally – transcribing and editing his writings. In his Mate-Woman, Jack found “a rare soul…who never bored me and who was always a source of new and unending surprise and delight.â€

Jack and his Mate-Woman plan their voyage.

Plato believed that communion with one’s lover was essential to growing back the wings of your horses when your chariot had fallen to earth, and it was Charmian that at last pulled Jack out of his Long Sickness. Together they found new ways to satisfy London’s hunger for adventure and challenge. In 1907, they took off in a yacht on what they hoped to be a seven-year voyage around the world. Jack wished to get away from public life altogether, and to test himself again in a new endeavor. He taught himself navigation and piloted the yacht on the open water to Hawaii, the Solomon and Marquesas Islands and several small islands in between, where they encountered primitive and even cannibalistic tribes. Unfortunately, because of an incredibly severe sunburn Jack developed in Hawaii, when he discovered the new sport of surfing and obsessively rode the waves until burnt to a crisp, and an equally severe case of psoriasis that swelled his hands to twice their size, the couple had to cut their voyage short. Jack recuperated in Australia, and then he and Charmian sailed back home, arriving two years after they had shipped out.

In 1912, three years after returning from their last big adventure, Jack and Charmian signed on as crew to one of the last remaining tall ships sailing the ocean which was carrying cargo on a five-month journey from New York, around Cape Horn at the tip of South America, and finally up to Seattle. Together the couple worked, talked, read (Jack brought along 50 books), and made love. Jack spent much time in the high perch of the mizzen-top mast, reflecting on life. In the mornings he wrote his 1,000 words and Charmian typed them up.

Ranching, loving, and adventuring, London remembered these times as ‘â€far and away†the happiest of his life. “Life went well with me,†he said. “I took delight in little things. The big things I declined to take too seriously.â€

But it was not, sadly, a happiness that would last. Despite his efforts to pull out of his depression, Jack’s balanced hold on his thumos and his appetites would remain tenuous. He would soon lose his grip on them, leading to an ascension in power of his dark horse, a tragic imbalance in the forces of his soul, and an early demise.

Read the Entire Jack London Series:

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Boyhood

Part 3: Oyster Pirate

Part 4: Pacific Voyage

Part 5: On the Road

Part 6: Back to School

Part 7: Into the Klondike

Part 8: Success at Last

Part 9: The Long Sickness

Part 10: Ashes

Part 11: Conclusion

_____________________

Sources:

Wolf: The Lives of Jack London by James L. Haley

Jack London: A Life by Alex Kershaw

The Book of Jack London, Volumes 1 & 2 by Charmian London (free in the public domain)

Complete Works of Jack London (all of London’s works are available free in the public domain, or you can download his hundreds of writings all in one place for $3, which is just plain awesome)

Tags: Jack London