Teddy Atlas was born to a well-respected doctor in a wealthy part of Staten Island. Most kids like him end up going to an Ivy League school to become some sort of white collar professional. Teddy? Teddy dropped out of high school, went to jail, and ended up becoming a trainer to 18 world champion boxers, including heavyweight champion Michael Moore, who defeated Evander Holyfield for the title in 1994.

Today on the show I talk to Teddy about how and why he took the path he did in life. Teddy explains how he ended up boxing under legendary trainer Cus D’Amato, and how Cus guided Teddy towards becoming a trainer himself. Teddy then shares stories of training kids in the Catskills, taking them to unsanctioned amateur fights in the Bronx, and the lessons he learned from boxing and his father about personal responsibility, managing fear, overcoming resistance, and what is means to be a man.

Show Highlights

- Teddy’s early relationship with his father

- How Teddy ended up on the streets as a dropout

- How Teddy found boxing

- The brilliance of Cus D’Amato

- The “smokers” of the tough streets of NYC

- The importance of a father figure to a troubled young man

- What is a champion?

- Why every man needs to meet resistance

- Why it’s harder to quit than it is to fight

- How Teddy learned to be a man

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

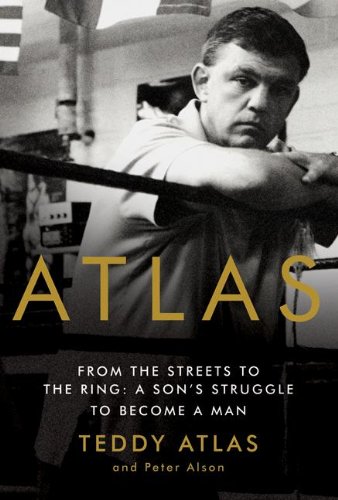

- Teddy’s book, Atlas

- On Taking a Punch

- Cus D’Amato

- Kevin Rooney

- The 14 Best Boxing Movies

- A Manly History of the Sweet Science

- Rocky Marciano’s Fight for Perfection In a Crooked World

- A Man’s Search for Meaning Inside the Ring

- AoM’s Boxing for Beginners series

- AoM’s Boxing Basics

- The Power of Mentoring

- The Rise and Fall of the American Heavyweight Boxer

Connect With Teddy

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Recorded on ClearCast.io

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

MSX by Michael Strahan. Athletic-inspired, functional pieces designed for guys who are always on the go — available exclusively at JCPenney! Visit JCP.com for more information. Also check out his lifestyle content at MichaelStrahan.com.

Policygenius. Compare life insurance quotes in minutes, and let us handle the red tape. If insurance has frustrated you in the past, visit policygenius.com.

Duke Cannon. Superior-quality grooming goods for hard-working men are tested by soldiers, not boy bands. Visit dukecannon.com and get 15% off your first order with promo code “manliness.”

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. Teddy Atlas was born to a well-respected doctor in a wealth part of Staten Island. Most kids like him end up going to an Ivy League school, to become some sort of white collar professional. Teddy? Well, Teddy dropped out of high school, went to jail, and ended up becoming a trainer to 18 world champion boxers, including heavyweight champion Michael Moorer, who defeated Evander Holyfield for the title in 1994.

Today on the show, I talk to Teddy about how and why he took the path that he did in life. Teddy explains how he ended up boxing under legendary trainer Cus D’Amato and how Cus guided Teddy towards becoming a trainer himself. Teddy then shares stories of training kids in the Catskills, taking them to unsanctioned amateur fights in the Bronx, and the lessons he learned from boxing and his father about personal responsibility, managing fear, overcoming resistance, and what it means to be a man.

After the show is over, check out our show notes at aom.is/atlas. Teddy joins me know via Skype. All right, Teddy Atlas, welcoming to the show.

Teddy Atlas: Thank you. Appreciate it.

Brett McKay: So you are an ESPN analyst for the sport of boxing. You’ve also trained 18 world champions, and you’re also the author of the book It’s Atlas: From the Streets to the Ring, a Song’s Struggle to Become a Man. You’ve also started a podcast, The Fight.

I just finished your book, Atlas. It’s an amazing story. It’s about your story of how you became a world class boxing training. What’s interesting is the story of how that process began begins when you were a child. You were the son of a respected doctor, who worked really hard, but somehow, despite being the son of a respected doctor, you end up being a high school dropout and you start committing crime. How did that happen?

Teddy Atlas: My father was a GP, a general practitioner, on Staten Island. He took care of everybody. He took care of all the poor. He took care of people that fell through the cracks. As part of that, he built this hospital that had 22 beds in it. It was called Sunnyside Hospital before … was built. He took care of people that … This was way before the idea of Obama Care. There were no HMOs. Really there was basically nothing, if you didn’t just have a doctor like this, and there wasn’t too many of them, I don’t think, that existed. Or you’d wind up in a clinic. The clinic, it might not be the greatest care in the world.

My father wanted these people to have the best care possible, so he built this hospital so they would get the proper hospital care, and he would absorb the cost. The people that had money, that had proper insurance, that would obviously keep the place open. As I said, the rest of it, he’d find a way to absorb it. He would just make a little less money, that’s all.

This hospital lasted for about 25 years, and then the city built a bridge. They came in, and where the hospital was was where the highway was going to be. So they bought it from him. They tore it down. He wound up finding another hospital a few years later, called Doctor’s Hospital, with 60 other doctors. He was the original founder.

The only way I could be with him was to go on house calls. He did house calls until he was 80, charged them five dollars. He didn’t charge when he went to a lot of places. He went into the projects. He went into a lot of places that a lot of other doctors didn’t go. If it called not to charge, he didn’t charge. So to steal time, and that’s what I was doing, I was stealing time … I was just a kid. I was only 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. I kept going, maybe 12, 13. That’s how I got to be with him, was to go on house calls, go to the hospital when he went for the visits.

I guess I wanted him to be at baseball games. I wanted to throw a football with him. I wanted to do other things. This is going to sound selfish, and it is, it is selfish, because I was just thinking about what I wanted, obviously. We all have that habit at some point. So even though I was with him, it was only under these conditions, where it was on the terms of his life, on his turf, so to speak. I guess I wanted him in other places in my life.

So in my infinite wisdom of basically being an idiot, as I got older, I started to get in trouble because … I realize it now. The people that got his attention were the injured, the fractured, the messed up in some cases, and the sick. So I got sick. I got sick in a different way, you know? I started getting on the streets and getting into things, not good things. I thought it would get his attention. That was obviously I guess the definition of a misdirected kid. I definitely was misdirected.

I’m not trying to make it more or better than it was. There’s a righteousness in thinking that you’re doing something, that there’s a cause behind it, there’s a purpose behind it, there’s a right behind it. I guess that’s where the word is derived from. I did think there was a right behind it. I did think that it gave me the key to the place I wanted to go, which was to him.

It got out of control, quite frankly. I got to bad places. I’m blessed. I’m in a good place. I got to a good place, but unfortunately, it took a couple detours to kind of get there.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I mean, you ended up in prison a few times. Did that get his attention? I’m sure it did, but not in the way you wanted.

Teddy Atlas: Yeah, it got his attention, but it wreaked havoc on my home because he was a believer that you were accountable. He was the greatest teacher I ever had. He didn’t talk a lot. The only person he talked a bit to was me, when we were on our car drives for house calls, when I would ask questions. He was a believer in doing, not speaking.

He was a great teacher in action. I learned from him, the most important thing, was to be accountable for your actions. It was maybe a lesson I didn’t want to accept at that point. It’s one thing talking about being accountable. There’s another damn thing about being accountable. The idea seems pretty damn good until sometimes it’s there.

To give you an example. I was a kid, I was wayward on the streets, and I got hit with a tire iron one time in a fight. My friends took me to his office, bleeding all over the place. I thought I had the privilege of going right to the front of the line. The nurse took me right to the front of the line. When he saw me, he said, “Let him wait with everybody else.” My father had the biggest practice on Staten Island, probably one of the biggest practices in New York, because he took care of everybody, took care of the people that didn’t have anything. So I waited four hours, whatever it was.

When it finally came my turn, the nurse did what a nurse does. She came with the needle of Novocaine. He looked at her and he said, “What is that for?” Obviously she said it was to inject the Novocaine, and obviously he knew, but he said, “He doesn’t want that. If he’s going to live a life like this, he’s gotta know how it feels.” Of course I said I didn’t want it. I got 15 stitches put into my head without Novocaine. Not the worst thing in the world, but not the greatest thing either.

So when I wound up in prison, my father wasn’t going to give me Novocaine for that. He refused to pay bail. Again, you do something, you accept what goes with it. You accept being in jail, in this case, Rikers Island. It took my mother, who obviously didn’t come from the exact school that he came from, she’s a mother, so a little different. It took her threatening him, took a little time to eventually get him to put up bail, to get me out. He was right. My mother was right, too. She’s a mother. But he was right. Ultimately, he was right.

Again, I was getting his attention, but obviously when you get to that kind of confused place, things are confused. Things are a little haywire. Listen, maybe this is human nature. I don’t want to say this, and I’ve never said this before. It just came to me now. I hate to say it as I’m saying it. You’re supposed to say the truths that we know, if we’re going to talk. We’re supposed to at least. Maybe I was trying to get even with him. Maybe I was trying to hurt him. Just now it hit me.

How could I avoid the possibility that that could have been possible? I hate to because he was the greatest man I knew, but as I speak, yeah, that’s a possibility. You know, lines get blurred. It’s possible that line was blurred into there, trying to get his attention, but at the same time, in my selfish world, trying to get back at him maybe a little bit, that I didn’t have what I wanted.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Was it during this time, this tumultuous time in your young adult life, that you discovered boxing? Or had you boxed even as a child?

Teddy Atlas: Yeah, I boxed as a teenager. It was during this time, it was a little before this time, but it was right at the beginning of this time, where I was getting into fights on the street. I was hanging out down in the tough neighborhood. A friend of mine was a boxer, Kevin Rooney, who later on led Mike Tyson, when Cus D’Amato passed away, to world titles and made a lot of money. He was my childhood friend. We hung out on the corner together, down in the Stapleton area of Staten Island, and I followed him to the gym.

It was a PAL gym, a little dingy place. That’s all it needed to be. PAL is Police Athletic League, which they no longer exist in New York, but at that time they did. It was a haven for a lot of kids. I went in there with Kevin and boxed in there. Then later on, when I started getting into more trouble, I got an opportunity to go upstate with Cus, which was provided by Kevin, obviously. Well, I shouldn’t say obviously. It turned out that Kevin wound up going to Cus. After he won the New York Golden Gloves, he went upstate to Cus D’Amato, who was semi retired, to train with him to become a pro, ultimately.

About four months after Kevin went up there, I got into serious trouble where I was facing serious time, 10 years. At that time, during the period that I was going to be out, where my father finally did pay bail, I was going to be out. Kevin didn’t want me to get into more trouble, so he said, “Why don’t you come up to Catskill and stay here with Cus and me?” So I wound up going up to Catskill, continuing to box at a higher level. I won the Golden Gloves up there, the Adirondack Golden Gloves. The story went to that, it transitioned to that place.

Brett McKay: Right, and that’s where you began getting your feet wet with training. How did that happen? Did Cus see something in you, that you could be a potential trainer, and he started nudging you in that direction?

Teddy Atlas: Cus was a master psychologist, manipulator. Don’t take the wrong way, because you can be a good person and know how to maneuver, manipulate people. That’s part of the magic of being successful with people, being a mover of people, being a motivator, an inspiration to people. Cus had that ability, and he used it when he needed to. He said I was a born teacher. It sounded good. He said that I was born to teach and that even though I had no interest in being a trainer at the time, he said that I could help people, I could do more than I could even do for myself if I was to become a champion, that I could develop fighters and help people get to a place they wouldn’t normally get to, themselves, and I’d be with them during that journey, a piece of me would be in the ring with them. That’s the exact way he put it, to try to, again, to maneuver me to do something I wasn’t inclined to do.

I wasn’t inclined to dedicate my life to being a trainer, to helping other people. I was still at that selfish phase where … Look, success is attached to selfish, too. It’s not like you have to apologize for it all the time, unless it gets out of hand. But I was at the place where I wanted to be a fighter. The idea was I was going to turn pro. I had an injury. I had a back injury. Cus used that situation to talk me into being a trainer. It didn’t take with me right away, but he kept at it.

I was a believer in loyalty. Again, it was taught by my father, the man who didn’t talk to much. Loyalty is attached to commitment. loyalty is attached to doing what you’re supposed to do, right? loyalty, commitment, keeping your word, living up to whatever it is that you’ve obligated yourself to. So that was something that was important to me. When Cus said I couldn’t fight, I couldn’t go somewhere else. There was no thought of that. If Cus said I couldn’t, I couldn’t. The option was go back on the street, doing what I was doing, or become a trainer.

Eventually, Cus got me to that place. It took a little while. We took some side roads to get there, that got me in trouble again, but eventually I kind of succumbed to Cus’s insistence that I would be a good trainer. Then he started calling me the young master. Again, he understood how to move people. He understood the psychology. He understood what you needed to hear. So I eventually stayed up there at some point, and I started training all these fighters.

I started developing a gym. You gotta remember, Cus was semi retired at the time. There was nobody up there. There was me, Kevin Rooney, maybe three other people, maybe four. When I, an 18, 19-year-old kid, started putting time into training kids in the gym, kids started coming. They started coming from all different areas. Next thing you know, we went from having nobody in the gym to 20 people, then 30, then 40. We had a real gym. 50 people. I trained them all. I trained the amateurs at night.

Jimmy Jacobs, who was very close, best friends with Cus, wealthy man, owned the biggest fight film collection in the world, him and Bill Cayton. Later on, the fight fans know who they are, they were the guys that managed Mike Tyson’s career at its most formidable stage. They basically funded Cus. They sent pros up there. I would train the pros in the day, and I would train amateurs at night.

I had no time, but it was good. I was committed to something. I created a real gym up there, with Cus’s belief behind me. That’s all I needed, his belief behind me. Again, I wasn’t getting paid anything, but Cus knew how to pay me. He would call me the young master. I think people listening understand that. You need to hear things like that sometimes. You don’t know if it’s always true, but you hope it is. It feels good. At the time, you probably wouldn’t be lying if you said it felt just as good as getting paid. Maybe later on it might not, but at the time it did. I was in there day and night, in that gym.

Then after about four, a few years, I was up there about seven years training fighters it turned at the end. But after several years of developing this gym, a guy named Mike Tyson came along. I developed him for another four years before I wound up leaving.

Brett McKay: One part you dig into in the book, about how you trained these young fighters, were you take them to these smokers. I think it was down in the Bronx, right? What were these? I’ve never heard of these before, but they just sounded really intense.

Teddy Atlas: Yeah, they were intense. Again, people that are not knowing of what it is are going to say it sounds dark and dangerous. Maybe it is. Maybe it did, but you have to understand, they were in the south Bronx where there was nothing but bombed out buildings and people in stairwells shooting up, and lost people sometimes on some of the streets. To a certain extent, the police didn’t go to certain neighborhoods. They left it alone a little bit, unless they were forced to go. You’d have a lot of bombed out buildings. Then you’d have a building that was there, that was actually maybe the safest, most positive thing in the neighborhood. It was a boxing club. The one I went to a lot was the Apollo, then later the Jerome. Then there was Castle Hill. There were so many of them.

The ones in the Bronx was the Apollo. It was right where the L, the L would run right across on the same level as it. It would shake the whole building. Sparks would go up. It would rumble by. You couldn’t hear anything for those couple minutes. Three flights of steps to get up there. As I said already, you’d walk past, you’d smell urine, you’d see discarded needles. You might see somebody possibly shooting up.

So yeah, as I say it now, people will say, “Teddy, what do you mean it sounds like it could be a little dark and dank?” Yeah, it had that, but it was the safest place for these kids, anywhere from ages 10 … I’ll tell you, sometimes maybe a little less. Again, I’m going into that area where people are going to say, “Is that responsible?” Well, is it responsible being in a neighborhood where you could get shot? Is it responsible where dope is very readily available, where you could get hit over the head with a pipe, stabbed? But now you had a place where hopes were formed and developed. Hope and dreams, that’s not dangerous. That’s what this place was.

There was a few of them around. There were non-sanctioned fights. Again, yeah, there was no doctors. The AAU at the time was supposed to overlook boxing, and then later on it was called the ABF I think, the American Boxing Federation, USA Boxing. But they weren’t in these places. These places, they were on their own. It was a chance for the proprietor of the place to charge three dollars at the door, sell little cups of rum, beers, food, and you’re able to help yourself with the rent. That meant keeping the doors open for hope, where these kids could come and they could train.

They could train, they could box, they could have a chance to get out of those places, have a chance to become Sugar Ray Leonard, or all these great fighters that they saw on television and they heard about on the radio with their fathers, maybe their uncles, somebody in their family, maybe a neighbor. They could get a chance to become something, a chance to feel better, to feel better about where they were, about who they were. It was important. It was the most important place in the neighborhood.

Now maybe you understand. I gave you both sides. I mean, the other side is tough, but without this side, it’s unredeemable. With this side, it’s redeemable. There’s a purpose to it. The place would be packed. It was a chance for kids, after the trainers did all that work teaching them the basics for months, for them now to find out if they could be a fighter, see what it was, to get experience.

You could catch with your father all day on the sidelines, out in the street, or in the driveway, if you’re lucky enough to come from a place that had a driveway. These kids weren’t. You could play catch with them all day, but then there came a time you had to be in the game. Now in the game, maybe that ball gets thrown the same way looks different. Why? Because somebody is watching, because it’s a game. Now you get a chance to get up to bat.

You learn all these things, how to hit a bag, how to throw a jab straight, how to throw right hand, how to follow with a hook, how to move your head to avoid punches, and now you get a chance to get the real experience, to find out can I do it? Do I want to do it? Can I make the right choices, when the choices come? You start learning how to be a man. You start learning how to grow up. I mean, and nobody outlines that to you. You’re learning to be a fighter, but you’re learning a lot more than that.

So that’s what a smoker was. You go into these places, and you’re a nervous kid. You’re walking up those steps. You got a chance to think about turning around. That’s another part about being a man, another part of growing up. Do I keep going? Do I find an out? Do I get out? Do I escape? Or do I keep going? What do I do? You get up there, and you got the Spanish music blaring from four foot speakers and the pompom drums and all that going on. You’re nervous.

I used to joke with the kids. I said, “Don’t worry, I’m not going to tell anybody. Nobody else can see it.” They used to look. “What do you mean?” “You know, see your heart beating out of your chest, where your shirt is going up and down.” They would look at their chest real quick, to see if it was true, because they knew what they felt. I said, “Don’t worry, nobody else saw it. All these other kids in there, they feel the same way.”

You started to teach them how to control their emotions, started to teach them what it was all about. You started to teach them that it was okay to be scared. Everyone else is scared. You just wouldn’t know it by looking at them, but you wouldn’t know it by looking at you, either. You don’t even realize it. You’re taking the first step already in overcoming it, by not showing it, and by dealing with it. Then they get in the ring, and they fight.

I’ll give you an example, an extreme example. I had a kid named Main Moore. This kid came to me in Catskill Gym because he was getting picked on, his lunch money was taken. He had no father. A lot of my kids had no fathers. It’s not an accident they didn’t have fathers. That’s why they came to the gym. They were looking to find the replacement for what a father would have gave them. Not just in the mentoring. That was part of it. Somebody caring, somebody telling them when they’re doing something right. Somebody’s gotta be there to tell you that. Or when you’re doing something wrong, somebody’s gotta be there to tell you that. It’s important. It can’t always be a woman. Not saying women … Of course they can do the job, but sometimes it’s gotta be a father.

This kid Main Moore had no father. He heard about the gym, and he started showing up. The funny thing was, he would show up and he’d leave, show up, leave. I’ll tell you one thing: as a trainer, you become a psychologist, without going to school. If you don’t understand the psyche of a human being, you’d better get the freak out of this business. It ain’t just about Xs and Os. It’s about people. It’s about how people feel and how they want to feel and what they’re not feeling.

After a few times of seeing this kid dart in and out … He was 80 pounds. He was 11 years old. 80 pounds. Finally one day, I said, “Come over here.” I had already gotten sort of the profile, if you want, of Main. He name was Main Moore. My kids in the gym, I asked about him, and they told me everything about him. “Yeah, he’s got no father. He gets picked on by a kid named Ghoul, takes his lunch money.” Stuff like that. So now I got what I need from my kids. The next time he comes in, I said, “Come over here.” He’s looking around, like, “Are you talking to me?” “Come here.”

I show him how to throw a jab. I throw a jab out by the mirror. I said, “You try that.” He tried it. I said, “That’s good. That’s good. You could have a good jab.” Then I tell him to throw a right hand. “That’s good. Wow.” I said, “Have you trained somewhere else?” He looks at me like I’m crazy. He says, “No.” “You sure? Because I don’t want to find out you trained somewhere else, and I’m taking someone else’s fighter.” “No, no, no. I didn’t train anywhere else.” “All right, good. All right. Come up here tomorrow. Bring gym shorts, stuff. Six o’clock, be here. We’ll start training.”

And that was it. That’s what he needed. I would teach him. He picked up very fast. Then when it came time to get in the ring and boxing, sparring, then he would fall apart. He wasn’t ready for that. It was too much. The funny thing was, I was a guy that came from this troubled past. Where do you think the gym was? Of course, where else? Above a police station. What’s across the hall, in a little place called Catskill? Of course, a court room. We’re in Catskill. They didn’t lock the doors. We had the court room at night, nobody there most nights. Court was open whenever it was, during the day, usually. So we have the court room, we’ve got the police station downstairs.

When Main, the first time I put Main in to box, he ran right out of the gym, started crying, because he was scared. He probably figured that he couldn’t handle this, obviously, figured he was yellow. Well, why wouldn’t he figure he was yellow? He got his lunch money taken every day. I would go out of the gym, have some of my older kids keep it going, and I’d go out there and talk to him. The funny thing was, there was no better place to talk if you had to sit down. Go in the court room.

I had fun with it a couple times. I remember one time thinking, after we did this a few times, because it took a while with Main, to get him to that place, I remember at one point I’m sitting in the judge’s chair. I couldn’t help but think, “You know what? It’s a lot better sitting here than on the other side where I used to sit a few years ago.” I kind of thought maybe I had the right to sit there now, or if I didn’t, I still was going to do it anyway because it was my own way of kind of getting back something a little bit.

So we would talk. I would tell him, “I want to tell you a story.” He’d be crying, and then he’d start calming down a little bit. I’d say, “I know it’s got nothing to do with you, but when I was a kid, I used to get picked on.” So you could imagine what a shock it was because I run the gym, and I’m known as a former fighter and all that stuff. This kid looks up to me. He says, “You used to get picked on?” I said, “Yeah, believe it or not. Yeah, yeah, I got picked on. Some guy used to take my lunch money.” Now, he doesn’t know I know everything about him. He said, “Well, what did you do?” I said, “I used to give it to him, and then I would go home and I’d cry. Then I’d feel terrible, but I wouldn’t tell anybody.”

He said, “What happened?” I said, “One day I just got tired of being hungry. I got tired of feeling this way. I started to realize that I’m going to keep feeling this way unless I do something about it. I started to realize that the way I feel and what I have to do is two different things. If I do something, it’s only going to last for a minute. How long does a fight last, before somebody breaks it up? A minute? 30 seconds? But if I keep letting this guy do this, and I keep going through what I’m going through, I’m going to keep feeling this. It doesn’t go away. I feel it at night. I feel it in the morning. I feel it during school. It’s forever.”

He said, “What happened?” I said, “You know the garbage pails where you dump your trash?” He said, “Yeah.” I said, “Well, one day the guy asked me for my money, and I didn’t give it to him.” He said, “What happened?” I said, “He wound up in the garbage pail.” He said, “Is that true?” I said, “Yeah.” He started laughing. He said, “I never knew you were afraid.” I said, “I’m afraid all the time. Like you just said, you’d never know it, but I’m afraid of things all the time. But I’m more afraid of how I used to feel when I didn’t do something about it, when I didn’t stand up for myself. I’m more afraid of that because I know how long that lasts. I know that lasts forever. I know the other thing doesn’t last that long.”

So we went back in the gym. The next day, I get him in the ring again. We might get into two minutes before he’d break down. Go the court room, sit in the judge’s chambers, have a talk. After about a week or two of this, he got through a whole round, he got through two rounds, he got through three rounds, he got through four rounds.

I took him to the Bronx. It was time to fight. But I had to find the right guy. I found a kid named Raul Rivera. Raul had the same problems as Main. He was scared. He was insecure. He had no father. He had no confidence. He was picked on. I put them together, and I’m telling you, it was the worst fight ever for people to watch. They grabbed each other. They looked at the referee. They held on to each other. They probably threw about a half a punch each for the whole three rounds. But it was the most beautiful fight I ever watched because it was allowing the kid Main to deal with what he had to deal with at the right temperature, and to get through what he had to get through.

I put them in six times in a row, six weeks in a row, with each other. Now, the proprietor, Nelson, said, “Teddy, you’re making me throw up. I can’t watch this stuff no more. I mean, really. I can’t watch this. You’re killing me.” I said, “Look, you’re going to keep watching it. You’re going to keep watching it because this is what they need.” You know what? By the sixth time, they were fighting. They weren’t grabbing. They weren’t looking at the referee. They were fighting. Even Nelson had to say, “I cannot believe it. I cannot believe these are the same people.” That’s what we did.

Brett McKay: Yeah. It sounds like you weren’t just teaching these kids how to box. You were teaching them to be men.

Teddy Atlas: Yeah. I mean, you weren’t separating the thoughts that way or articulating it that way, but yeah. Yeah, they were learning the magic of being a grownup, of being a man. You know what the magic is? To learn and to understand that you have the choice of how you behave, not somebody else, not circumstances, not the environment. Even the environment of the south Bronx, tough environment. Beautiful people there, great people, tough environment. Tough environment. Those things did not dictate choice. They did not dictate control. They did not tell you how you had to behave. You did. You did. You did.

They learned that. They learned that no matter what, no matter how many of these things were lined up there to have basically excuses to be less, that at the end of the day, it was your choice. Nobody else’s. Your choice of how to behave. Your choice of what you were going to do. They learned that. You know what that is? That’s the prelude to being a man. That’s what it’s about.

Brett McKay: You hit on this as you were describing the story of the smokers, where it’s just this terrible place, people shooting up, dope, urine, whatever. That’s kind of like the story of boxing in general. Ever since the beginning, boxing has been criticized as barbaric, low brow. It’s been looked down upon by the media. I’m talking going back to the 19th century.

But for students of the sport, you hear these amazing stories of individuals from a lot of times minority groups, Irish, Black, Jews, who were in lower class. They could have gone to a life for crime, but then they found boxing. For just a few of those guys, they became champions, champions of the world. For most of those guys that didn’t do that, they still learned about discipline, controlling emotions, managing their fears, those skills that you’ve been talking about throughout these stories.

Teddy Atlas: And they became champions. What is a champion? For me, I don’t know when I was finally smart enough to understand this, but for me now, it’s got less to do with gloves on your hand and how hard a punch you can take, than how great of endurance you have, both emotionally, psychologically, and physical endurance. It’s got a lot less to do with how fast your hands are than it has to do with how you behave.

That can be equated into anything. And it is, whatever it is. Whether it’s to be a teacher, a carpenter, a board member, a CEO, a guy working as a laborer, to become a champion, to become someone who can make his own choices, that is completely free and completely separate from the environment, completely separate from what’s going on in your world, what’s going on around you.

That you can make a choice. That you can say, “Today, I’m going to be the best freakin’ carpenter in the world. I’m going to be the best freakin’ teacher in the world. I’m going to be the best freakin’ laborer in the world.” Whatever it is, because you know that it’s you who makes that choice. You know that you’re in control of that. That’s my definition of becoming a professional, doing what you need to do, no matter what goes on around you, no matter how you feel when you wake up that day. It’s becoming a man. It’s becoming a whole person.

You know the greatest thing I can say about boxing? If somebody said, “Teddy, you’ve got one minute. Describe boxing.” I would say, “Okay, the world is not fair sometimes.” Now they’re listening. “Oh, okay. All right.” Maybe sometimes you feel like you haven’t been treated fair. You feel like you haven’t been given as good of cards as your guy down the street was, to play with.

So this is what boxing is: on one given night, you can get in the ring. If you trained hard enough, if you cared enough, if you were determined enough, if you were driven enough, if you were prepared enough, on one given night, no matter where you came from, no matter who your parents are, no matter your ethnicity, your religion, anything, on that one given night, you could make a choice to be the best. You, despite everything that happened up to that point, can have your hand risen as the best, as the champion of the world. Where everything is fair and right on that one given night. That’s boxing.

Brett McKay: You’ve trained, what is it, 18 world champions, including Michael Moorer, who was the heavyweight champion when he beat Evander Holyfield. During all this time, you’ve been training kids, amateurs, pros. What’s the hardest thing to teach a boxer? Is it that idea that they’re in control, that they’re in charge, that they can make the choices? Is that the hardest thing? Or is there something else?

Teddy Atlas: Yeah, that’s a good question. The hardest thing to teach a fighter, the hardest thing to accept, to get a fighter … I’m going to use that word instead of your word.

Brett McKay: Okay.

Teddy Atlas: No, no, it’s all good. The hardest thing to get somebody to accept, that’s what a teacher has to do, is that, and I’m putting this in the most simplest way, you either have reasons why and you develop those reasons why you can, or you have excuses why you can’t. Bang! That’s it. I know that’s, as I said, as simplistic as you can get, but it’s not that simple when you try to unravel it and you try to execute it. That’s what it is. You either have reasons and you take those reasons, because people said you couldn’t do it, because they said you were a yellow coward, because your stepfather says you’re a piece of garbage, because you got no father, because your mother is on drugs, whatever it is. Whatever it is, you either make those reasons why you’re going to do it, because you just want to do it, because you just want to feel good.

You know what else? You just want to know who you are. A kid just wants to know who they are. They want to know, “Am I somebody good? Am I somebody worthwhile? I heard a lot of people say I wasn’t. Am I somebody worth of something, of success, of feeling good? Am I allowed to feel good?” You either have reasons to go forward in those directions, or everything I just said. Take everything I just said, and use it on the left-hand column, as excuses why you won’t and why you can’t. You get them to understand that, and you’re on your way.

Brett McKay: Something you’ve also said in your interviews and in your book is that a fighter isn’t really a fighter until they’ve faced resistance. What’s an example of a fighter who hasn’t faced resistance?

Teddy Atlas: Forget about a fighter. You in life, in anything. You’re not a teacher until you’ve had a kid in the classroom trying to put the classroom on fire. I’m kidding around. I’m exaggerating. I hope there’s nobody trying to put their teachers’ classrooms on fire out there. Please don’t do that. But until you’ve gotten a kid that doesn’t let you go home so easy, that is not so agreeable, that is not so committed to what you want them committed to, until you overcome that, you’re not a teacher.

Until you, as a doctor, you open up somebody and veins that were supposed to be bleeding are bleeding, you’re not a doctor. You’re just a guy that understands the anatomy. You’re a guy that passed a lot of tests. You go into a courtroom and all of a sudden the district attorney throws a curve ball, all of a sudden the judge says, “No, you can’t use that brief today. I don’t care that you put four month’s work into it. No, you can’t.” You’re not a lawyer. You thought you were a lawyer because you got a diploma that’s up on the wall that looks pretty freaking good, but you’re not a lawyer. Not until you deal with that, not until you overcome something.

You’re not a fighter. It’s the same thing. You’re just a guy that’s in good shape. You’re a guy that has physical abilities. You’re a guy who inherited good genetics. You’re a guy who is going through an athletic exhibition. Great. Looks good. But until there’s resistance, until there’s something to overcome, you’re not a fighter.

Brett McKay: That’s when a lot of fighters, who maybe have that talent, those genes, when they face that resistance, that’s when they give up. They don’t know that idea that it’s harder to give up than it is to fighter.

Teddy Atlas: Yeah. That idea is so simple. I’ll say it again. I’ve been saying it for whatever amount of time we’ve been talking, in so many words, in different words, but I’ll say it again. It is harder to quit than it is to fight. When you fight, it’s over with in a second, 10 seconds, really. I mean, really. Am I exaggerating? A world title fight, if it goes the distance, lands 36 minutes. That’s a blink of the eye in somebody’s life, a blink of the eye. It’s a second. Something difficult you gotta deal with, a minute, half a minute, five seconds. Whatever it is, that’s how long it lasts, to deal with it.

But if you don’t fight, whatever your fight is, you don’t deal with it and you quit, you submit, you give in, that doesn’t go away. That’s there all day, all night. It comes at the worst times to you, 2 o’clock in the morning. You can’t sleep. You’re laying in bed. You get up, you walk into the washroom, you look in the mirror, and there it is. There it is. There it is. It’s still there. The next day, still there. The next day, still there. Yeah. If you understand it in the way I just said it, the real way, yeah, it’s damn easier to fight than it is to quit.

Brett McKay: You’ve spent your career training men, young men, to be fighters and men. You started this when you were 19, 20. How has your conception of what it means to be a man evolved since then? I’m curious, obviously your father has a big influence on what you think of what a man is, that whole idea of accountability, but as you’ve gotten older, have you noticed that your father’s influence, has it gotten stronger? Or maybe even Cus’s? Or maybe other people? Or maybe you’ve discovered things on your own, on what it means to be a man.

Teddy Atlas: It was my father. Cus taught me how to put it into words, taught me how to teach it, how to articulate it, yes. He put it into form, into usable form, Cus did. Brilliant man, special man. But the real architect of this, if you will use such a description, the former of this, my father. There’s no greater teacher than example. There’s no greater lessons than to watch, to see. No matter how this man felt … I mean, this is a guy who no matter how he felt, he did what he had to do. This is a guy who had to get surgery after … Back in the days when surgery in certain ways was much more invasive, much more dangerous. I mean, my father had I don’t know if it was a double or triple hernia. Whatever the hell they called it.

He got it as an intern when he was interning. He went to the NYU medical school, and he interned at Bellevue. He told me that when you got out of Bellevue, you were ready for everything. He saved an obese person’s life, it turned out, when he was a young intern. The person, it was a woman, had collapsed on the street. He got her off the street, pulled her to wherever he had to. She had a heart attack. Basically, he saved her life, and he formed a hernia.

Well, he didn’t have time to take care of that. So 35 years later, finally he had to get it. It was strangling him. Now, I didn’t know nothing about that stuff. One day I walked into his bedroom. I should have, but again, I’m 7 years old, I’m 8 years old, whatever the heck I was. I walk in, I open the door, and there was a big mirror that was right to the left that could show you what was to the right of the room. I looked in the mirror, and there he was, in a way I’d never seen in my life.

He was bent over, obviously in pain, and he had this contraption around him, around his midsection, around his groin area. It was a truss. I didn’t know what the hell it was. It was made out of leather, and it was to keep his intestines from popping out. It was to keep the hernia, which was popping way out, in place. That’s what they had in those days. I was confused. He got angry. He said, “Close the door. Leave the room.” Of course I never forgot that.

You know what that told me? I didn’t know a damn thing, but I knew he was in pain. I knew my father was in pain every day, and he still did everything he was supposed to do, every day in pain. Every day. He waited 35 years to get the surgery. He got it done at Doctor’s Hospital, that he founded.

This is crazy. My father was eccentric. Okay. I think great people are. I think special people are sometimes. Maybe we call it eccentric, and maybe it’s really special. Maybe it’s what works for them. He actually had started the process by giving himself some, just as he was walking into the hospital, so by the time they got him ready, he saved them time. He was already starting to be a little bit ready for the anesthesia and stuff I guess, whatever they have to give. I mean, he knew what to do.

So they got him on the stretcher, and they’re talking him to the OR room. He says, “Hold on a minute. Stop here at the station.” Nurse’s station. “Stop here.” Doctor Atlas, we’ve got to get you into the OR. “No, no, no. I gotta stop here. I just gotta go over a couple of orders for a few patients.” He had a sense of humor that was very different than other people. He said, “Just in case this don’t go right, I gotta make sure this poor lady gets out of here Monday. I gotta make sure she gets discharged. And I gotta make sure this other guy gets his medicines changed. So stop at the station.” He stopped at the station, looked at the orders, made a few adjustments, and then he said, “All right, go ahead. Let’s go. Take me.”

He was supposed to be in the hospital at least eight, nine days, in those days. In the hospital one day. Now, was it the right way to do it? No. No, it wasn’t. Doctors are the worst patients, we get it, but he could do it. He could do it. He understood it was a matter of dealing with the pain. It was a matter of what his responsibility … He was back working in his office three days later. He knew he could do it. Was it convenient? No. Could you do it? Yes. That’s what I learned, and that’s how I learned it.

To answer your question, I think I’m remember it, even though I went down this road. You said, “What is it? What is it to be a man?” Convenience. That’s what it is. To understand the difference between convenience and responsibility, that’s it.

Brett McKay: That’s it. Well, Teddy, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about what you’re doing, the podcast, anything else you got going on?

Teddy Atlas: They can go to the podcast. I think you go on … I don’t know much about this stuff. I’m a caveman. I’m the most unsophisticated media guy in the world. Somebody fortunately does this for me and talked me into doing it. I have a podcast. You go on YouTube and you put in The Fight with Teddy Atlas. I know there’s some iTunes and some other stuff that you can go on, on something.

Brett McKay: Sure. What do you talk about on your podcast?

Teddy Atlas: We talk about life. You know what I said from the beginning? I said I’m going to use this podcast to talk boxing, but to use boxing to connect the dots in life. For me, everybody is fighting. I don’t mean it that way. I don’t mean it the way it sounds, because there is a lot of fighting going on out there, but what I mean is, we’re all in a fight. It’s just a matter of what the hell you’re fighting for. For me, what better to use, to kind of take people through things, than boxing, to explain the fight they might be dealing with.

I talk about boxing. I connect the dots with life. I try to go places where maybe people would like to go, but they just don’t know how. I try to show them how.

I just recorded my book into an audiobook. It’s coming out next month, so hopefully that’ll be something, too, that people will find interesting.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Teddy Atlas, thanks so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Teddy Atlas: It’s my pleasure. Thank you.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Teddy Atlas. You can check out his book. It’s called Atlas: From the Streets to the Ring, a Son’s Struggle to Become a Man. It’s a great story. Also check out his podcast, The Fight. It’s available on anywhere you can listen to podcasts. And check out our show notes at aom.is/atlas, where you can find links to resources, where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM podcast. Check out our website at artofmanliness.com, where you can find our podcast archives. We’ve got over 500 episodes there, a couple episodes about boxing, as well as thousands of articles we’ve written over the years. A lot of articles about boxing as well, so if this is something that interests you, check it out. If you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the Art of Manliness podcast, you can do so only on stitcherpremium.com. Head over to sticherpremium.com and use promo code manliness to get a month free of Stitcher Premium. After you sign up at stitcherpremium.com, you can download the Stitcher app on IOS or Android and start listening to ad-free episodes of The Art of Manliness.

If you enjoyed the show and got something out of it, I’d appreciate it if you’d take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. It helps out a lot. If you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think would get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you not only to listen to the AOM podcast, but to put what you’ve heard into action.