The Art of Manliness makes no secret of the fact that we draw inspiration from the past in order to help modern men live better lives. We particularly pick up tips from my grandfather’s generation, as thinking about his life was one of the catalysts for starting the site.

After four years of blogging, I’ve gathered that not everyone is particularly keen on that approach.

Whenever we do a post that lays out lessons from the lives of great men or from the so-called “Greatest Generation,†it invariably attracts comments like:

“X famous man wasn’t so great. He was a drunk/adulterer/slave owner…[fill in the blank with the perceived tragic flaw].”

Or-

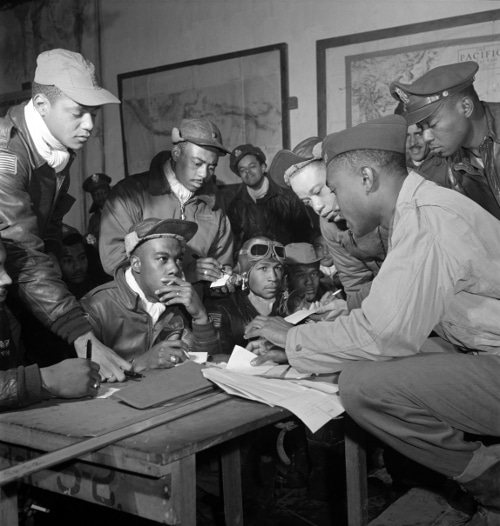

“The Greatest Generation…pffft! Those racist/sexist/homophobes weren’t any better than anyone else.”

It seems that in our cynical age being inspired by men of the past has gone out of style along with having heroes or ideals of any sort.

But this wasn’t always so. And today we’d like to make a case for finding inspiration in those who have come before.

A Brief History of History

When you think about history, you may conjure up a memory of a boring class in high school or college in which you had to memorize a bunch of dates and names and battles. Thus, you likely feel that history is a rather straightforward business—a just the facts, ma’am subject.

But as its name suggests, history is simply a story, and who is telling that story and how they tell it makes all the difference in the world.

Thus the story that gets handed down to each generation and how we feel about that story is always changing. History is quite a malleable thing and can be, and indeed is, shaped and re-shaped all the time.

For many centuries, history was looked at as a subject that was important to learn, and its importance was derived from the way it could be used to teach young people vital lessons about who they were and how to live. For the ancient Greeks, history’s purpose was to teach morality. Plutarch, the famous Greek historian, explicitly stated that his intent in writing the Lives of Famous Greeks and Romans was to provide moral instruction to his reader.

This conception of history as moral instruction held firm in the West up through the 19th century. If you look at books for young folks from the 1800’s, they’re packed with examples from the lives of great men on how to do great deeds, be successful, and become honorable citizens. Some historical figures were portrayed as heroes, men to emulate, and some were portrayed as villains–their lives served as lessons to the student of mistakes not to repeat.

This was also a time of great reverence and respect for the nation’s leaders. Take a look at the eulogies written after the death of George Washington, for example. They’re amazingly flowery and over-the-top, making him out to be a saint of unassailably sterling character.

But in the wake of disillusionment that arose after WWI, historians of the 1920s began to reexamine history and its dominating figures and events with a much more cynical eye. Writer William Woodward invented the word “debunk†during this time (riffing on the practice of “delousing†soldiers in WWI), and picked George Washington as the object of his de-bunkification. Woodward painted Washington not as a dashing hero, but as grossly incompetent, boorishly clumsy, and greedy for fame and money.

The trend of debunking the traditional view of history accelerated in the 1960s, when new historians sought to tell the stories of women, minorities, and other groups that had all but been ignored for centuries. As their untold stories emerged, some historians also took another look at the way traditional history had been portrayed, examining the standard narratives from a new angle, and arguing that what was once seen as good and heroic, really wasn’t so noble after all. Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States is the most popular example of this approach to history.

A good illustration of the transformation in how we view and use history can be found in a very interesting article about the ways in which the modern Boy Scout handbook has changed since it was first published in 1911. Author Kathleen Arnn describes how in the original handbook, the young reader learns about:

“America’s great moments through the heroes who lived them: George Washington, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Daniel Boone, Betsy Ross, Johnny Appleseed, and most of all, Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln is a hero among heroes, a central figure in the handbook’s discussions of patriotism and of virtue. He is “in heart, brain, and character, not only one of our greatest Americans, but one of the world’s greatest men.” The manual relays the whole story of his life, from his lowly beginnings that taught him the value of hard work, to his education, and to his presidency and untimely death.”

In the modern edition, references to great men of the past have almost entirely disappeared:

“There are, by my count, four heroes in the book. They are the founders of Scouting: British founder Robert Baden Powell, the naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton, outdoorsman Daniel Carter Beard, and James E. West, who led the BSA through its first 30 years. Each gets a sentence and a picture. American heroes, so numerous and colorful in the original handbook, are almost absent. Washington and Lincoln are each mentioned one time. Here is their sentence: ‘We remember the sacrifices and achievements of Americans with federal holidays, including observances of the birthdays of George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'”

While “revisionist history†gets a bad name, it’s a needed thing; the revision of history by each generation and storyteller has been going on since the beginning of time. Our views of history change, and should change, as we learn new facts and hear new perspectives.

However, as with most cultural movements, in a well-intentioned attempt to dislodge the pendulum from being stuck too far in one direction, the weight swung too far in the other.

These days the stuff of Zinn is standard fare in college classrooms, and history is rarely used as inspirational material. If you talk about a good aspect of a great man or generation, you are expected to immediately follow up with a list of their flaws and mistakes as well. If you don’t, you’re seen as a rube who has swallowed the traditional version of history and isn’t in on the new “secret†information that has been revealed. The self-satisfaction of those who consider themselves in the know and like to give you the “real scoop†is invariably palpable.

Thus the fact that we present the good bits about the lives of great men without cataloging their failings is a source of irritation for some who read the blog. (And this isn’t a liberal vs. conservative thing by the way: we get “Theodore Roosevelt was a socialist and Lincoln was a tyrant!” along with “Churchill was a racist and Hemingway was a misogynist!” in equal measure.)

But we don’t concentrate on the achievements and wisdom of history’s great men because we are ignorant of their blemishes, or of history as a whole. Kate taught college history, and I studied classical history as an undergrad, and we read many history books each year. We’re by no means professional historians, but we’re hardly uneducated dolts either.

In actuality, the more we read about history, the more it inspires us. Because we approach our studies with a certain frame of mind.

A Mature Mindset

When you’re a kid, you tend to see things in black and white. Heroes are super good. Bad people are rotten to the core.

As you get older, you start to see things in shades of gray. You learn that people are more complicated and complex than you once knew. This maturing perspective has its drawbacks—it’s harder to be passionate about things and have heroes when you know they’re not perfect, but it’s also essential to learning, growing, progressing, and being effective in the world.

Men who cannot be inspired by history are stuck in the black and white children’s view of the world. A famous man can have a multitude of great traits, but if he also had a big flaw, then nothing can be learned from him. Out goes the baby with the bathwater.

But we’re big believers in holding onto to that slippery baby. The reason we focus on the good aspects of the lives of great men on the site is not because we are unaware of their flaws, but because the purpose of the articles is not to provide a full biographical sketch, but to discover what these men did right and explore what honorable manliness looks like. They’re specifically about the good bits. Maturity means knowing the time and place for things; you don’t enumerate a man’s failings when giving his eulogy, for example. Again, it does not mean you’re ignorant of those failings, but that you choose to focus on certain aspects at certain times for certain purposes

A mature mindset also involves the ability to be inspired by the good bits despite the bad bits and realizing that one does not necessarily negate the other. The mature man does not turn his eyes from a historical figure’s flaws, but he does not let those flaws eclipse the lessons to be learned from the person’s life. He is able to sift the wheat from the chaff.

How does a man gain this sifting ability? He is able to view historical figures just as he views himself. He himself has a great many flaws—and yet he loves himself all the same! When he thinks about himself, he thinks of his good qualities, and would never say that the mistakes he’s made blot out his redeeming characteristics. This is also how men see those they love. A man’s father might have made some mistakes, but he still speaks of him as a great man and seeks to emulate the things he did right.

The reason we can be so generous with ourselves is that we seek to understand our mistakes with rationalizations like, “Well, that was my view then, but it’s changed now.†“Everyone was doing that at the time.†“I just got caught up with what was happening.†“I was depressed then.†“I couldn’t have gotten the job if I hadn’t said that.†“I didn’t know all the facts at that time.†And yet all these mitigating factors apply not just to you, but to all the men of history!

But…But!

Ironically, those who are unable to see the flaws of great men more generously through the prism of the person’s circumstances, tend to be those who also disparage their accomplishments, chalking them merely up to, well, circumstances.

For example, if you praise the frugality of my grandfather’s generation, someone will retort that Gramps was only able to avoid debt because of things like the GI Bill and low housing prices. They argue that the Greatest Generation was only great because of the advantages they enjoyed that we are no longer privy to.

But greatness is not begotten from circumstances, but from how those circumstances are used and turned to a man’s favor. Or in other words, while Gramps may have enjoyed lower housing costs, he was also quite happy about living in a 750 square foot house in Levittown as opposed to a 4,000 square foot McMansion (the average home size has more than doubled since the 1950s).

As Frederick Douglass put it:

“I do not think much of the good luck theory of self-made men. It is worth but little attention and has no practical value. An apple carelessly flung into a crowd may hit one person, or it may hit another, or it may hit nobody. The probabilities are precisely the same in this accident theory of self-made men. It divorces a man from his own achievements, contemplates him as a being of chance and leaves him without will, motive, ambition and aspiration. Yet the accident theory is among the most popular theories of individual success. It has about it the air of mystery which the multitudes so well like, and withal, it does something to mar the complacency of the successful.”

And of course it isn’t hard to see in hindsight the advantages others enjoyed that led to their success. And yet I can easily see how my grandchildren could point to numerous advantages that we have…and yet how little we turned those advantages to our favor and let things go to pot.

And this really gets to the crux of my generation’s tendency to disparage the past–we don’t feel like we’re doing too hot, and we want to believe that our lack of accomplishments is due to circumstances entirely outside of our control. Douglass again:

“It is one of the easiest and commonest things in the world for a successful man to be followed in his career through life and to have constantly pointed out this or that particular stroke of good fortune which fixed his destiny and made him successful. If not ourselves great, we like to explain why others are so. We are stingy in our praise to merit, but generous in our praise to chance. Besides, a man feels himself measurably great when he can point out the precise moment and circumstance which made his neighbor great. He easily fancies that the slight difference between himself and his friend is simply one of luck. It was his friend who was lucky, but it might easily have been himself. Then too, the next best thing to success is a valid apology for non-success. Detraction is, to many, a delicious morsel.”

A man can be showered with numerous opportunities, and yet squander them all away. Circumstances help, but personal responsibility and agency determine our fate.

And this is why a man should study and let himself be inspired by history! It can teach him how to turn his own opportunities into success and character.

My generation tends to believe that everyone is special and that no one is better than anyone else. “Every generation is just the same,” they say. But while it’s true that every generation has its own strengths and weaknesses, what those particular strengths and weaknesses consist of is unique. And if we humble ourselves, we can work on our weaknesses by learning from the strengths of the men of the past, just as we hope that our grandchildren will learn from the things that we’re doing right.