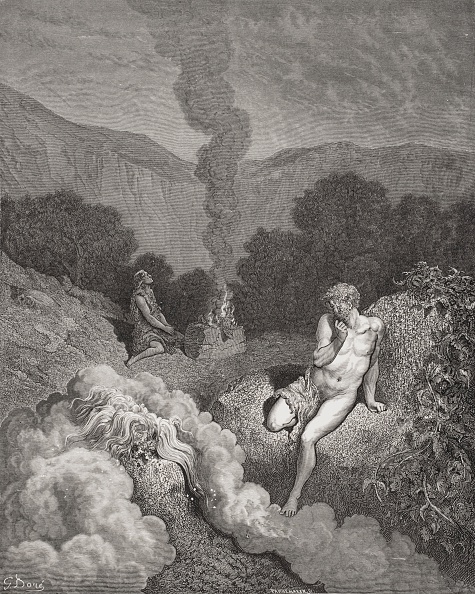

“Now Abel was a keeper of sheep, and Cain a tiller of the ground. In the course of time Cain brought to the Lord an offering of the fruit of the ground, and Abel for his part brought of the firstlings of his flock, their fat portions. And the Lord had regard for Abel and his offering, but for Cain and his offering he had no regard. So Cain was very angry, and his countenance fell.” –Genesis 4:2-5

For millennia, readers of the Bible have puzzled over this passage in Genesis. Why does Yahweh accept Abel’s offering of meat, but not Cain’s of fruit? What accounts for the seeming capriciousness of the Almighty’s favor?

The most popular interpretation is that the brothers presented their gifts with two different attitudes: the scriptures mention that Abel brought the “firstlings” of his flock, but don’t apply that designation to Cain’s yield, leading to the conclusion that the former gave the best he had, while the latter offered inferior gleanings.

That’s not the only theory on the matter, however.

Noting that Abel’s name is mentioned first, despite his being the younger brother, some scholars, like Hermann Gunkel, have posited that God simply has a preference for him, and more broadly, for his vocation, arguing that “The narrative maintains that Yahweh loves the shepherd and animal sacrifice but wants nothing to do with the farmer and fruit offerings.”

Why would the Lord (or the author of Genesis) prefer shepherds over farmers?

In the Jewish historian Josephus’ interpretation of the tale, the brothers’ divergent occupations breed divergent sets of virtues.

As a shepherd, Abel followed the “way of simplicity,” wandering where he pleased, and being content with “what grew naturally of its own accord.” As a result, he was “a lover of righteousness” and “excelled in virtue.”

Cain, on the other hand — whose name means “possession” — was a “covetous man” who was “wholly intent on getting.” His desire for gain led him to look beyond what grew spontaneously and to invent the practice of farming — to “force the ground” to bear fruit. The more he grew, the more he wanted, and the more desirous he became to protect that which was his. Cain became “the author of measures and weights” and the founder of commercialism, ownership, and divisions between public and private life. He “set boundaries about lands; he built a city, and fortified its wall, and he compelled his family to come together to it.”

His progeny in turn further established a more settled existence, and invented things like metallurgy and music.

But in tandem with this “civilizing” process, Cain and his subsequent lineage became more and more sinful. The original farmer “only aimed to procure every thing that was for his own bodily pleasure, though it obliged him to be injurious to his neighbors.” His love of luxury developed a moral softness in himself and in his posterity, so that each generation became “more wicked than the former.”

In other words, Josephus theorizes that Cain’s offering was rejected by Yahweh, because it was the offering of a farmer, and farming would lead to commercialism and civilization, and civilization would bring both greater complexity and greater temptation and depravity. Farming symbolizes the beginning of vice — a fall from the innocence, generosity, and primitive simplicity represented by pastoralism.

Greater civilization can not only be seen as leading to a weakening of moral virtue, but a weakening of distinctly masculine virtue as well.

In fact if you look at the story of Cain and Abel from another angle, it becomes a kind of explanatory tale in which two archetypes — shepherds and farmers — symbolize two types of manhood, and the way in which the latter inevitably kills off the former.

Shepherds vs. Farmers

Agriculturists and pastoralists historically found themselves in conflict, as they lived two very different lifestyles, which called for the development of two very different sets of traits:

Shepherds Wander and See More of the World; Farmers Lead a More Settled and Constricted Existence

The main difference in the resources shepherds and farmers tend/produce, is that the former’s move (and can be moved), while the latter’s are literally rooted in one spot.

Early shepherds lived a life of great openness; they often didn’t legally own the land they let their livestock range upon, nor did they fence pieces of land in. They didn’t reside the entire year in one place, but rather took their herds to pasture in different locations, depending on the season. Because of the necessity of this travel, shepherds saw more of the landscape, met more people, and explored more of their world.

Since a farmer’s crops were rooted in a single location, so was his whole life. He planted his crops in the ground, and there they remained to be cultivated and harvested. A farmer could build his homestead with a sense of finality, and he and other farmers formed towns that were equally permanent. Land was parceled out and marked off. Fences were built. Life was settled down.

Shepherds Live a Harder and Simpler Life; Farmers Live a Softer and More Complex Life

Because farmers knew they’d be living in the same place for a long time, they were able to create homes that were more permanent, elaborate, and comfortable. The intermittent, seasonal nature of farm work also permitted time to pursue other interests, while well-established, well-populated towns allowed for greater specialization. From agricultural communities, then, grew advancements in knowledge and technologies.

The farmer’s life was softer and more complex, but also more artful.

The life of shepherds was harder and evinced a kind of primitive simplicity.

Because they moved so much, shepherds had to travel light. And while pastoralism required less intensive, hands-on work, tending sheep necessitated more constant vigilance, and left less time for innovating in arts and other fields. The work itself demanded fewer tools, and thus less technological innovation. Greater emphasis was placed on improvisation, on making do with less. The shepherd’s life, if it subsequently rarely rose above a subsistence level, was also more Spartanly stripped down; he neither had much, nor needed much.

Shepherds Have Bigger Families and Wider Patrilineal Ties; Farmers Have Smaller, More Insular Families

One of the most crucial differences between farmers and shepherds was the portability — and thus vulnerability — of the latter’s resources. It’s much easier to steal a flock of sheep than a field of crops. Shepherds thus had to direct much of their energy to guarding their livestock against theft, and this need for vigilance informs nearly everything about pastoral culture.

For one thing, it encouraged having large families, full of ties that bound not only the nuclear family but the extended one as well. The more male brothers, sons, uncles, and cousins who were part of your clan, the more men you could count on to guard your flock, and thus the larger, and more prestigious, your flock could be. Not only was a deep, wide patrilineal line a major asset to a shepherd, his network didn’t end with branches born of blood; he also made alliances with men with whom he was not biologically related, adopting these “kin” into his “family.” A shepherd needed to be part of a large, loyal tribe to survive, thrive, and gain and maintain power.

While the farmer’s life was certainly organized within a patriarchal structure as well, he wasn’t as motivated to have a large family, or cultivate wide-ranging ties, because he didn’t need as much help working the land. Further, land was not infinitely dividable as an inheritance for a farmer’s sons and was a more finite resource. Farmers’ families were thus smaller and more insular.

Shepherds Co-Exist With Wild Nature; Farmers Tame and Cultivate Nature

A central difference between shepherds and farmers was their relationship to nature: shepherds tended to it, while farmers cultivated it.

Shepherds co-existed with nature, while farmers transformed it. Shepherds were immersed in its wild state, while farmers tamed that wildness — pushing the perimeter between their homes and the rawness of nature further and further out.

Shepherds Are Impulsive and Daring; Farmers Are More Patient and Controlled

The key qualities to a farmer’s success were prudence, self-control, patience, diligence, and a propensity for long-term planning; he greatly needed the ability to delay gratification. He had to plant and tend to crops that wouldn’t be ready for harvest until months after seeding time. Every day the chores of farm work awaited, and had to be completed over and over again. He had to be patient with his lot, and patient with the weather as well — with whatever the season would bring. The farmer had to set a stoic face to the forces of fate and nature; an overweening ego could not survive the buffeting of such uncontrollable forces.

The key qualities of a shepherd’s success were bravery, toughness, strength, cleverness, and cunning. Status and prestige came in growing the size of your flock, and this growth partly came by stealing sheep from the flocks of others (the point of stealing sheep was not to gain sheer numbers, but as we’ll see, to convince the victim to ally with you). These raids were risky, stealth operations necessitating courage and prowess in navigating a mountain at night, and making off with livestock without being caught and physically attacked.

Such theft attempts were common and did not violate the shepherds’ code of ethics; rather, they were almost ritualistic and constituted a reciprocal competition based on mutual respect — a way to test and earn manhood and honor. A shepherd gained honor by demonstrating his adeptness at raiding another’s flock and by defending his own; skill in these areas earned you a reputation — which you outwardly expressed with a heated pride — which deterred others from messing with you and your flock. You showed weakness by letting someone steal your sheep, and not trying to steal them back, plus some. Such weakness made you a greater target. This was honor at its most basic: if you get hit, you must hit back. Eventually, if one shepherd showed his superiority in raiding another’s flock, and thus gained his admiration, an alliance between the two men would be formed, allowing the successful raider to increase the protection, and thus the size, of his own flock.

Two Necessary Archetypes of Manhood

Farmers thought of themselves as superior to shepherds, who they viewed as lazy, shiftless, morally inferior, uncultured, socially backward rubes. Farmers saw themselves as smart, civilized, and morally disciplined — the masters of man’s highest aim: to be in control of your own land.

Shepherds believed themselves superior to farmers; they thought agriculture was safe, effeminate “women’s work,” and saw it, and the towns it birthed, as filled with a bourgeois culture that was sedentary and corrupt. Shepherds were proud of their rangy toughness, nimble simplicity, closeness to nature, and bold bravery. Though they didn’t own the land they lived upon, they believed their freedom made them the true kings of it.

While real shepherds and farmers saw their lifestyles as part of an irreconcilable dichotomy, when viewed as symbolic archetypes, perhaps we can see them as neither good nor bad, but two necessary parts of manhood.

Farmers represent the idea of being a good man: having self-control, dignity, foresight; being a patient creator and builder.

Shepherds represent the idea of being good at being a man: embodying the core virtues of masculinity — courage, honor, mastery, and strength.

The task for modern men is not to be one or the other, but to embrace the ethos of the farmer, while not entirely letting go of the way of the shepherd.

In The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis, Leon Kass points out: “Though He respected Abel’s offering, God speaks only to Cain; Cain seems to hold more interest, being both more promising and more problematic.”

Cain symbolizes farming, and thus civilization, which holds both sticky pitfalls and rich potential. From civilization can come many great developments in philosophy, morality, art, technology, and knowledge. But it can also make men too comfortable — too soft, too decadent, too settled. Within the confines of civilization, men can lose their sense of boldness, toughness, adventure, and risk-taking. The fruits of civilization can be sweet, but only if they don’t come at the price of enervating vice, and at the expense of one’s essential masculinity.

After God rejects Cain’s sacrifice, he is angry and downcast, and Yahweh counsels him:

“If you do what is right, will you not be accepted? But if you do not do what is right, sin is crouching at your door; it desires to have you, but you must rule over it.”

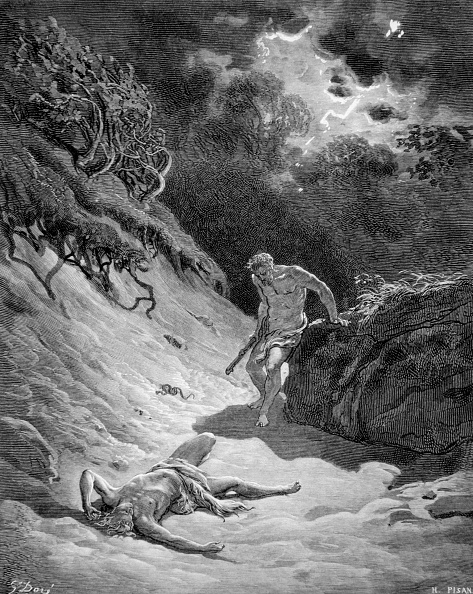

Of course, Cain doesn’t do what is right; he slays his brother Abel. In reaching for culture, for progression, for comfort and convenience, he sees no other choice than to kill the symbol of that which is more “barbaric,” more primal.

Rather than mastering his desires for the fruits of civilization, and letting his flintier, more strenuous side act as a check on its excesses, he buries that blood and heedlessly pursues decadence.

Perhaps we instead must learn to be the keeper of our brother, to preserve the ethos of the shepherd. Perhaps in order for the sacrifice of our lives to be accepted, we must maintain a wild heart.

Listen to our podcast with modern-day shepherd James Rebanks, in which we discuss these same themes and more:

________________________

Insights on the intersection of shepherding, farming, and manhood, as well as the distinction between being a good man and being good at being a man, from The Poetics of Manhood by Michael Herzfeld.