In coming across Robert Louis Stevenson’s essay, “The Lantern-Bearers,” a few months ago, I discovered an image that has stuck with me like few things I have ever read. I have pondered it many times since, and I thought that it was especially apropos to share during this “season of lights.â€

In the essay, Stevenson begins by recalling the autumn holidays he spent as a boy in a small coastal fishing village. He describes the things he and the other boys did for fun, and then turns to describing their favorite and most memorable form of amusement:

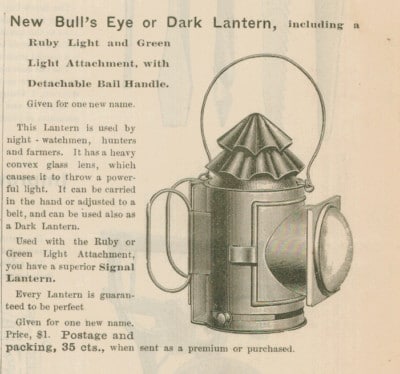

“Toward the end of September, when school-time was drawing near and the nights were already black, we would begin to sally from our respective villas, each equipped with a tin bull’s-eye lantern. The thing was so well known that it had worn a rut in the commerce of Great Britain; and the grocers, about the due time, began to garnish their windows with our particular brand of luminary. We wore them buckled to the waist upon a cricket belt, and over them, such was the rigour of the game, a buttoned top-coat. They smelled noisomely of blistered tin; they never burned aright, though they would always burn our fingers; their use was naught; the pleasure of them merely fanciful; and yet a boy with a bull’s-eye under his top-coat asked for nothing more. The fishermen used lanterns about their boats, and it was from them, I suppose, that we had got the hint; but theirs were not bull’s-eyes, nor did we ever play at being fishermen. The police carried them at their belts, and we had plainly copied them in that; yet we did not pretend to be policemen. Burglars, indeed, we may have had some haunting thoughts of; and we had certainly an eye to past ages when lanterns were more common, and to certain story-books in which we had found them to figure very largely. But take it for all in all, the pleasure of the thing was substantive; and to be a boy with a bull’s-eye under his top-coat was good enough for us.

When two of these asses met, there would be an anxious “Have you got your lantern?” and a gratified “Yes!” That was the shibboleth, and very needful too; for, as it was the rule to keep our glory contained, none could recognise a lantern-bearer, unless (like the polecat) by the smell. Four or five would sometimes climb into the belly of a ten-man lugger, with nothing but the thwarts above them–for the cabin was usually locked, or choose out some hollow of the links where the wind might whistle overhead. There the coats would be unbuttoned and the bull’s-eyes discovered; and in the chequering glimmer, under the huge windy hall of the night, and cheered by a rich steam of toasting tinware, these fortunate young gentlemen would crouch together in the cold sand of the links or on the scaly bilges of the fishing-boat, and delight themselves with inappropriate talk. Woe is me that I may not give some specimens– some of their foresights of life, or deep inquiries into the rudiments of man and nature, these were so fiery and so innocent, they were so richly silly, so romantically young. But the talk, at any rate, was but a condiment; and these gatherings themselves only accidents in the career of the lantern-bearer. The essence of this bliss was to walk by yourself in the black night; the slide shut, the top-coat buttoned; not a ray escaping, whether to conduct your footsteps or to make your glory public: a mere pillar of darkness in the dark; and all the while, deep down in the privacy of your fool’s heart, to know you had a bull’s-eye at your belt, and to exult and sing over the knowledge.

II

It is said that a poet has died young in the breast of the most stolid. It may be contended, rather, that this (somewhat minor) bard in almost every case survives, and is the spice of life to his possessor. Justice is not done to the versatility and the unplumbed childishness of man’s imagination. His life from without may seem but a rude mound of mud; there will be some golden chamber at the heart of it, in which he dwells delighted; and for as dark as his pathway seems to the observer, he will have some kind of a bull’s-eye at his belt.

Thus, at least, looking in the bosom of the miser, consideration detects the poet in the full tide of life, with more, indeed, of the poetic fire than usually goes to epics; and tracing that mean man about his cold hearth, and to and fro in his discomfortable house, spies within him a blazing bonfire of delight. And so with others, who do not live by bread alone, but by some cherished and perhaps fantastic pleasure; who are meat salesmen to the external eye, and possibly to themselves are Shakespeares, Napoleons, or Beethovens; who have not one virtue to rub against another in the field of active life, and yet perhaps, in the life of contemplation, sit with the saints. We see them on the street, and we can count their buttons; but heaven knows in what they pride themselves! Heaven knows where they have set their treasure!

There is one fable that touches very near the quick of life: the fable of the monk who passed into the woods, heard a bird break into song, hearkened for a trill or two, and found himself on his return a stranger at his convent gates; for he had been absent fifty years, and of all his comrades there survived but one to recognise him. It is not only in the woods that this enchanter carols, though perhaps he is native there. He sings in the most doleful places. The miser hears him and chuckles, and the days are moments. With no more apparatus than an ill-smelling lantern I have evoked him on the naked links. All life that is not merely mechanical is spun out of two strands: seeking for that bird and hearing him. And it is just this that makes life so hard to value, and the delight of each so incommunicable.â€

Stevenson used the story of his boyhood lantern game as a way to segue into his criticism of the “realist authors†of his time, whose literature dealt with the average man and who, under the auspices of being completely true to life, painted him as a dull, one-dimensional character, without much inner life at all.

But Stevenson argued that just as an observer looking at the boys during their secret autumnal game would not have known about the lanterns hidden beneath their coats, those who judge other men from afar are often ignorant of the fact that the “average man [is] full of joys and full of a poetry of his own.†And, Stevenson adds, “to miss the joy is to miss all.â€

We do not always understand the things that give meaning to the lives of others. The globe-trotting playboy may look at the suburban dad who works a 9-5 job and pity him as a suffocated, lifeless, dullard, and yet that man may enjoy an unsurpassable joy in raising his kids. As William James, who believed that Stevenson’s essay deserved “to become immortal,†explains:

“Wherever a process of life communicates an eagerness to him who lives it, there the life becomes genuinely significant. Sometimes the eagerness is more knit up with the motor activities, sometimes with the perceptions, sometimes with the imagination, sometimes with reflective thought. But, wherever it is found, there is the zest, the tingle, the excitement of reality; and there is ‘importance’ in the only real and positive sense in which importance ever anywhere can be.â€

While Stevenson argued that even the most average seeming man has some of that joie de vivre inside him, I would submit that some men tend to the flame of their lanterns more diligently than others, allowing that flame to burn more brightly, and letting it animate their lives to a greater extent than most. And walking in this light leads them to greatness.

I actually came to the Lantern-Bearers essay by way of a 1985 lecture by Charles Scribner Jr., who for many years worked with the famous author, Ernest Hemingway.

In describing Hemingway, Scribner illuminates—quite literally—what the fire of a bulls-eye lantern might look like in the life of a real man:

“One of the obvious facts about Hemingway is that virtually all his life, from the time he was a boy until the time he died, he thought of himself as a writer—nothing else. That image of himself created his ambition, directed his will, supplied his greatest satisfaction.

I think that from the start there was a kind of enchantment about his commitment to writing. Robert Louis Stevenson, in his autobiographical essay “The Lantern-Bearers,†describes the excitement he felt as a boy when he and his comrades would meet after dark, each of them carrying a bulls-eye lantern under his top coat. All the lanterns were lit but kept covered for the greater part of the expedition. Then, at the end, they were uncovered and allowed to shine out full strength. But for those boys the bliss in the adventure lay in the knowledge that the lanterns were lit and burning brightly even in the dark under their topcoats.

Like all true artists, Hemingway kept his own lantern under his topcoat, hidden from outsiders; he would talk about it tangentially, if at all. But it was there all the time, the most important thing in his life.

As early as his high school days he had come to think of himself as a writer. It was a reasonable pretension. Words came easily to him, and he had a natural sense of style for putting them together. One of the results of his years at the Oak Park and River Forest High School was to bring him to a realization of his talent. In his senior year he wrote lively reports for the weekly school paper and short stories for its literary magazine. That is not an unusual combination of genres for a schoolboy, but Hemingway never gave them up. Throughout his career he wrote short stories and news reports.

The experience of seeing his work in print was as pleasing to him as it is to all writers, but in him it became an addiction. He was always on the lookout for material to use in a story; he was a magpie in that respect, industriously and almost by reflex storing away in his memory colorful bits and pieces of life…

When the time came for him to think about college, it could have been no great surprise to anyone that he chose instead a job as cub reporter on the Kansas City Star. He knew he had a bent for journalism and the job was in line with his ambition as a writer.

Hemingway’s six-month stint on The Star has been described as an apprenticeship. Valuable in many ways, it provided him with material he used for his later fiction. He learned how to dig out the facts of a story and he toiled to describe them simply and directly. He also learned to recognize a good story when he saw one. His image of himself as a writer had now developed into the reality of being a professional writer; status—and that particular status—was very important to him.

It is clear that as a writer Hemingway would develop still farther beyond the lessons he had learned in Kansas City. He would end up creating a style capable of representing events and truths that lie outside the scope of journalism, and to do that he had a certain amount of unlearning to do. His companions in journalism were impressed not only by his energy on the job but also by his interest in literature off the job. There was a bulls-eye lantern lighted under his coat.â€

Tags: Manvotionals