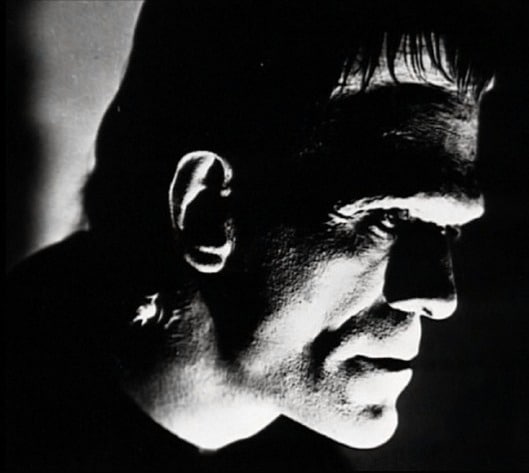

Victor Frankenstein does not get much attention in popular culture. It is Frankenstein’s creation – a nameless monster (often mistakenly called Frankenstein) – in all his green, bumbling glory that attracts the attention and the horrified screams of people worldwide.

To the contrary of how film directors and producers have portrayed Frankenstein’s monster, Mary Shelley wrote the character as an intelligent and physically astute being. He wasn’t a stiff, monosyllabic beast with a flat head and a bolt in his neck. And while Victor Frankenstein himself is often mostly ignored in media portrayals, he retains the image of a mad scientist. That’s about as far as we ever get in analyzing Frankenstein.

This is unfortunate, as some of the mistakes Frankenstein made along the way, mistakes which ultimately led to him losing everything he cared about – his brother, his best friend, and ultimately his wife – are incredibly instructive to any man who wishes to improve himself. After reading Shelley’s masterpiece, both previously and for this month’s AoM Book Club selection, my gut feeling was actually of sympathy towards the monster rather than Frankenstein.

While highlighting a character’s positive traits can be inspirational, it can also sometimes be quite educational to examine the ways in which he stumbles. So today we’ll take a look at Victor Frankenstein as a profile in un-manliness and explore what his flaws can teach us about what it means to be human, the importance of owning up to our responsibilities, and the danger in blaming anything other than ourselves for our mistakes.

Lesson #1: Unchecked Passion Can Be Dangerous

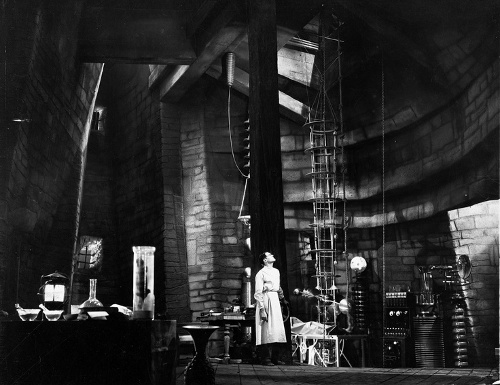

The creation of the monster was a long process. It didn’t happen overnight. It was months and months of studying and experimental tinkering before the creation rose to life. Frankenstein notes while narrating his story, “I seemed to have lost all soul or sensation but for this one pursuit.” His studies and his obsession “swallowed up every habit of [his] nature.”

While Frankenstein was away at college, he became utterly obsessed with finding out what the spawn of life really was. In spite of the insistence of his family and professors to give up this all-consuming pursuit, he continued on. He did nothing with his time but study this science of human animation and tinker in his lab. He lost sight of any other thing in life that brought him joy…so he really did become the mad scientist that we all know from pop culture.

What’s telling is that when Frankenstein took breaks to go home, his passion would be tempered, he would realize what truly brought him joy in life, and he would be happy once again. But then he’d return to college, and continue in his madness. It was almost an addiction.

While passion today is touted as a necessary and driving force in our career path, if unchecked it can lead to losing the things we truly care about in life. The late Steve Jobs is often looked up to (heck, even worshiped) for his brilliant business acumen and product innovation. But his passion and obsession for his company led to him being an angry and temperamental boss, and a mostly absent husband and father. What is more important in life? I can’t offer a one-size-fits-all answer, but Frankenstein himself gives us a great bit of wisdom while reflecting on this passion of his:

“A human being in perfection ought always to preserve a calm and peaceful mind, and never to allow passion or a transitory desire disturb his tranquility. I do not think that the pursuit of knowledge is an exception to this rule. If the study to which you apply yourself has a tendency to weaken your affections, and to destroy your taste for those simple pleasures in which no alloy can possibly mix, then that study is certainly unlawful, that is to say, not befitting the human mind. If this rule were always observed; if not man allowed any pursuit whatsoever to interfere with the tranquility of his domestic affections, Greece had not been enslaved; Caesar would have spared his country; America would have been discovered more gradually; and the empires of Mexico and Peru had not been destroyed.”

Lesson #2: Giving Up the Ship Won’t Solve Your Problems

One of my constant annoyances while reading the book was that Frankenstein incessantly blamed the ethereal forces of the universes for his problems. At one point, he comes close to giving up his pursuit of animating a lifeless object, only to be pulled back into his obsessions once again. Frankenstein notes, “It was a strong effort of the spirit of good, but it was ineffectual. Destiny was too potent, and her immutable laws had decreed my utter and terrible destruction.†Later he blames “chance – or rather the evil influence, the Angel of Destruction, which asserted omnipotent sway over me…â€

Frankenstein felt he was at the mercy of the fates and had no trust in his own willpower to overcome his dangerous passions. He had what’s called an external locus of control – a belief that you’re not responsible for your behavior, that life happens to you, rather than you making it happen.

A resilient man, on the other hand, seeks to have an internal locus of control – the confidence that one is the captain of his destiny and can pilot his ship wherever he wants it to go. He takes responsibility when things go awry and actively seeks to get back on course.

Everyone falls somewhere on a spectrum between the two perspectives, even changing depending on the situation. When we don’t believe we can solve a problem, we tend to assume the victim mentality and look externally to assign blame.

The reality, however, is that we have way more control over our lives and actions than we tend to think; when practiced, our focus and our willpower are incredibly potent tools for shaping our lives. Sure, circumstances will always have something to say, but if your life hasn’t gone the direction you thought it would, take action and don’t let it stay that way. One of our mantras here at AoM is that if you want to feel like a man, you have to act like one. And a man doesn’t blame his life on destiny or fate, he takes responsibility and assumes command of his actions. Which leads to our next lesson…

Lesson #3: When You Don’t Accept Responsibility, Your Mistakes Can Take On a Life of Their Own (Literally)

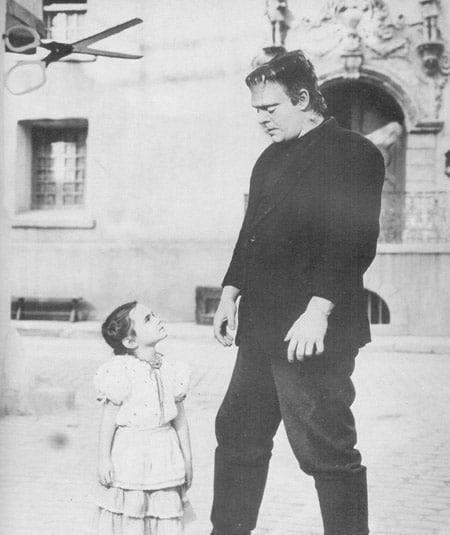

After the monster rose to life, Frankenstein was horrified at his creation and ditched. Plain and simple. He got out of dodge, ran home, and hoped that his perceived disaster would somehow remedy itself.

This is understandable. We’ve all run at one time or another from some problem we’ve created. And hopefully, we’ve come to learn that running only escalates those problems, and they can truly take on a life of their own. Think of the snowballing lie where you’re spending more time and thought on the lie than the reality of the situation. And those instances usually come back to bite us in the rear even worse than had we owned up right away.

What’s most frustrating about Victor Frankenstein is that he had multiple chances to take responsibility and own his mistakes and fix them, and each time he shrank like a coward and came up with excuses.

At one point early in the novel, the monster kills Frankenstein’s young brother and frames a woman in the village named Justine. She is caught and sentenced to die. Only Frankenstein knew the truth of the matter. He says, “A thousand times rather would I have confessed myself guilty of the crime ascribed to Justine, but I was absent when it was committed, and such a declaration would have been considered as the ravings of a madman, and would not have exculpated her who suffered through me.â€

His excuse is that the people in the village would not have believed his tale. How lame is that? And Justine is killed without Frankenstein uttering a word of truth.

When we create something awesome, we practically fall over ourselves to claim the credit. But when we create a problem, our natural tendency is to slowly walk backward while casually whistling the tune of abnegation and denial. But being a man means taking responsibility for all of our creations, both the good and the monstrously bad.

Humans are not perfect. Not by any means. But it’s within our power to correct the problems we create. And when we don’t exercise that power, our problems fester and only get worse. Think about the dentist. If you go every six months for regular cleanings, brush your teeth twice a day, and floss regularly, you’ll likely be just fine. But when you put off those appointments, when you slack on flossing, when you forget to brush every once a while, you end up being poked and prodded for two hours so they can give you a deep clean and fix the problem you created. Not fun. (If it seems like this is from personal experience, it is.) And that’s just with oral hygiene, let alone something far more serious.

Frankenstein at one point says, in regards to a potential solution to his monster problem, “I clung to every pretense of delay, and shrank from taking the first step.†Can’t we all relate? There are a whole host of reasons why ripping the band-aid off is a better solution than the slow peel. Most importantly, it’s the simple fact that a man takes responsibility for his life, and therefore the problems he’ll inevitably sometimes create.

I’ll leave this lesson with one final bit of advice from the reflective Frankenstein, “Nothing is more painful to the human mind than the dead calmness of inaction.â€

Lesson #4: Loneliness Leads Us Down Unhealthy Paths

One of the catalysts of Frankenstein’s unchecked and dangerous passion was simply that he was by himself at college. His friends and family weren’t around to give him balance and temper his flame. It wasn’t until he could hear the voices of those closest to him that he realized how selfish and frankly, crazy, he was being.

“Study had before secluded me from the intercourse of my fellow creatures, and rendered me unsocial, but Clerval called forth the better feelings of my heart; he again taught me to love the aspect of nature, and the cheerful faces of children… A selfish pursuit had cramped and narrowed me.”

Author Mary Shelley notes that the theme of loneliness and its effect on humans was important to her in this novel. In Frankenstein’s case, it can be argued that it’s mostly his loneliness that led to the creation of the monster.

Loneliness also plays out in the monster’s life. He turns to kill because he’s so lonely – nobody accepts him, he has no companion, and even his creator has rejected him. At one point he tells Frankenstein that if he simply had a female mate, he’d stop killing and run away to never be seen again. Frankenstein, who should understand the perils of loneliness, rejects this idea, however. So not only did loneliness lead to the creation of the monster, the monster becomes murderous and kills everyone close to Frankenstein because of his own loneliness. One can’t help but think of the mass shootings of the last two decades, and how most are perpetrated by males whose profiles include words like “isolated” and “lonely.” Would things have been different, even in just a couple instances, if loneliness wasn’t as pervasive in their lives?

Humans are not meant to live solitary lives. Science has shown again and again the importance of friends – in everything from stress levels to happiness levels, to life expectancy. What’s more telling, however, is a simple life experience. As an introvert, I often just want to sit at home and hang out with myself and my wife, and I quite love working from home, alone in my office. When I spend time with friends though, there’s just something that happens inside that gives me a more satisfying feeling with life. There is simply greater joy in my day-to-day when friends and family are a regular part of it.

While it can be and is a difficult and messy endeavor, be sure you have friends and family you can turn to, and perhaps more importantly, who can keep you accountable when you get off track. Victor Frankenstein isolated himself and paid dearly for it.

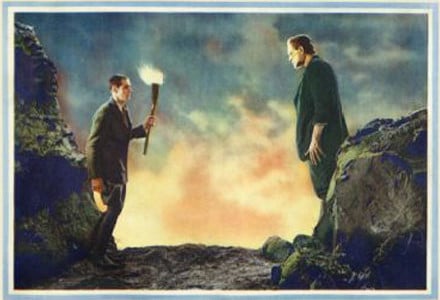

Lesson #5: Appearances Can Be Deceiving

This is the most heartbreaking lesson of all from the novel. The monster (for ease of identification, I’ve been calling it “the monster†the whole time – but it’s not really a fair assessment) is intelligent, reasonable, even caring. It strongly desires to interact with other humans and simply be loved. But, every single person he encounters shrieks and runs the instant they see him. He’s never even given a chance.

Frankenstein himself says, “Begone! Relieve me from the sight of your detested form.†The creature’s own creator refuses to see past appearances. Even later on, when having a discussion with the creature, Frankenstein observes, “I compassionated him and sometimes felt a wish to console him; but when I looked upon him when I saw the filthy mass that moved and talked, my heart sickened and my feelings were altered to those of horror and hatred.†Frankenstein begins to have compassion and to see past the ugly exterior, but in the end, his reliance on his senses takes over, and his heart doesn’t have a chance to respond.

The creature himself notes that “the human senses are insurmountable barriers to our union.†What a sad commentary on how powerful appearances are. Sure, they are important in business and in first impressions, but to let appearances be the final say in any judgment is simply not giving someone their proper worth as a person.

The creature has feelings of joy, hope, despair – isn’t this what makes us human? Our commonalities on the inside as people far outweigh our differences and our appearances. Don’t allow what’s on the outside to have the final say.

Let Frankenstein’s tale serve as a variety of lessons in how not to act like a man.