Editor’s note: This is a guest post from Andrew Ratelle.

“I see man’s mind cannot be satisfied

unless it be illumined by that truth

beyond which there exists no other truth.”– Paradiso IV.124-126.

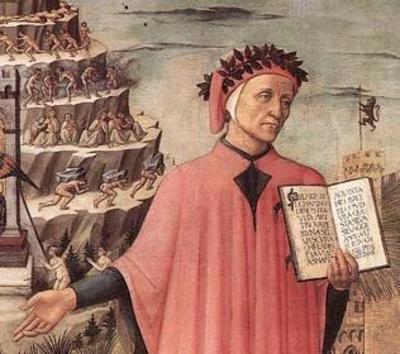

Auguste Rodin’s famous sculpture, The Thinker, is probably the single most well-known depiction of the poet Dante. Originally entitled The Poet itself, the statue has since become as much of an icon of the strength of the human intellect as the man who first inspired it. Crouched in life as in Rodin’s bronze over some of the greatest problems life has to offer, Dante remains one of history’s foremost thinkers, a visionary who places man at the center of his own epic journey between good and evil.

Born in Florence to a noble family in 1265, Dante Alighieri was a man whose life was shaped by conflict. After the defeat of the Ghibellines, the rival political power in Florence, Dante’s own party, the Guelphs, split in half and turned on itself for control of the city. Having made a name for himself as a statesman and “man of letters,” Dante was sent on an ambassadorial mission to Rome to help treat for peace. Detained there by Pope Boniface VIII while his political enemies seized control of the city, Dante was fined and eventually banished from Florence for his opposition to the new ruling party. He would never again return home. For the next twenty years, Dante lived as an exile until his death in 1321, during which time he penned one of history’s greatest epics.

A poetic journey through the flames of hell, purgatory, and heaven, the Divine Comedy takes place on a truly massive scale. Encompassing the entire breadth of man’s moral actions, it has resonated with each passing generation for the last seven hundred years, never ceasing to inspire readers of every walk of life with its immortal themes of sin, suffering, and redemption. Along with its author, the Comedy has long been a touchstone of the Western intellectual tradition, ensuring an enduring legacy for those who would seek to learn from the life and work of “the central man of all the world.”[i]

Lessons in Manliness from Dante

“Nobility, a mantle quick to shrink!

Unless we add to it from day to day,

time with its shears will trim off more and more.”– Paradiso XVI. 7-9.

Never underestimate the power of a well-rounded mind. Some two hundred years before Leonardo da Vinci and Galileo etched into tradition the archetype of the multi-talented Florentine, Dante had already taken the stage as a kind of “pre-Renaissance Renaissance man.” Though his renown stems chiefly from his abilities as a poet and writer, Dante maintained an enormous appetite for learning throughout his life.

The arts of war, politics, philosophy, linguistics, music, painting, and the natural sciences were all pursuits he engaged with the same discipline and intensity, completely immersing himself in a chosen subject for its own sake. Diverse though they were, much of Dante’s success lay in his ability to incorporate his many interests into the service of his larger work, creating a piece of literature that is at once an achievement in subject, style, language, and visual artistry.

The Divine Comedy is in many ways the first poem of its kind, an epic written not in the classical Greek or Latin, but the vernacular of the common people. To achieve this, Dante essentially standardized the language we now know as modern Italian, applying his abilities as a linguist to synthesize the varying dialects that stretched across medieval Italy into a single, cohesive whole. Likewise woven through the Comedy are many of Dante’s other scholarly interests, now conveyed to a new and broader audience through his skill with language. Set to an almost musical tempo, the Comedy’s narrative moves the reader through a vision of the afterlife that rivals the imagery of any artist, while taking on the world of politics, history, and even the metaphysical nature of the earth itself.

Breadth of study is no hindrance to a mind that can harness its resources toward a singular goal, bringing to bear the weight of one’s discipline and experience on the subject at hand.

“…for sitting softly cushioned,

or tucked in bed, is no way to win fame;

and without it man must waste his life away,

leaving such traces of what he was on earth

as smoke in wind and foam upon the water.

Stand up! Dominate this weariness of yours

with the strength of soul that wins in every battle

if it does not sink beneath the body’s weight.”– Inferno XXIV.46-51

Learn as much from experience as you do from books. To borrow a line from Mark Twain, Dante may have studied much, but he never allowed it to get in the way of his education. Scholarly work was an essential element to his intellectual formation, but he was far from letting it be the only one.

Not content with simply playing the part of the studious observer, Dante approached life with the same vigor he applied to his studies. He was, as he later remarks in the Inferno, as much of a glutton for knowledge as he was for experience. In his youth, he fought with sword and spear against the Ghibellines as a feditore, or heavy cavalryman, on the front lines of the Florentine army at the Battle of Campaldino and later at the Siege of Caprona. Six years later, he began a career in public life, serving on councils and in debates before eventually being elected to the office of Prior for the city of Florence. During his time in exile, Dante traveled extensively, often attending meetings and delegations to try to restore peace between the factions of the Guelph party and then returning home.

But it was far from a bed of roses. Dante’s intensity as an intellectual was likely the result of the fact that he experienced much of the darker side of life. By the time he began the Comedy, Dante was a man whom life had chewed up and spat back out. Hardened by war, conflict, betrayal, and the burden of exile, Dante had seen firsthand the coarseness of the world, and it left an indelible mark on him and his work. Gleaning as much from the rawness of life as from his subjects of study, Dante allowed his mind and poetic imagination to be shaped not just by the good or easy things in life, but also by its bitterness, truly making him a man who could reflect on the world as a man of the world.

“How hard it is to tell what it was like,

this wood of wilderness, savage and stubborn

(the thought of it brings back all my old fears),

a bitter place! Death could scarce be bitterer.

But if I would show the good that came of it

I must talk about things other than the good.”– Inferno I.4-9

Accept the consequences of your own moral vision. Moral courage can take many different forms. At times, it may require a man to defend the principles he lives by, or even to do the right thing regardless of the consequences. At others, it could mean something a little more basic.

Justice was much more than a nice idea in Dante’s mind. It was real, the standard of a higher moral order that bound the actions of all men. Right and wrong weren’t just arbitrary designations, but degrees of talking about the inherent value of human behavior. His life in politics and exile had shown Dante the face of corruption and treachery, and knew that the perpetrators of both and many more ills rarely received any punishment for their deeds. But that did not mean they shouldn’t be held accountable for what they did.

The standard that evil is to be punished and good rewarded is written into the very fabric of the Divine Comedy, and it’s a standard Dante uses to measure the deeds of all men, even his own. Moral judgments require courage, because in so judging, a man must hold himself and his own actions to the very same standard. The vision that allows one to see evil for what it really is also illuminates his own rights and wrongs. For Dante, a journey through hell, purgatory, and heaven isn’t just a matter of looking into the fate of other people, but a way of viewing oneself, facing up to both one’s strengths and weaknesses as they really appear.

“You have the light that shows you right from wrong,

and your Free Will, which, though it may grow faint

in its first struggles with the heavens, can still

surmount all obstacles if nurtured well.

You are free subjects of a greater power,

a nobler nature that creates your mind…

So, if the world today has gone astray,

the cause lies in yourselves and only there!”– Purgatorio XVI.76-83

At the end of the day, a man lives the life he chooses. Simplicity can matter as much as any level of depth or richness when it comes to creating a great work of literature. For all its timelessness and complexity, the Divine Comedy has a singular message at its core–how man, “subject to the justice of punishment or reward,” either “gains or loses merit by the exercise of his free will.”[ii]

Dante knew that men rarely live how they want, but they will always live as they choose. Though circumstance may often decide many things in one’s life, it cannot ultimately effect the control a man has over the direction he takes. Fortune may work for good or ill upon the path he walks, but it will always be the path he chooses to walk, just as it will always be his choice to move forward or to turn back.

In Dante’s mind, man was the ultimate custodian of his own fate. He alone was responsible for the outcome of his life from beginning to end, and it was he that had to accept the consequences of his choices. With all earthly distinction faded away, the characters in Dante’s Comedy are seen solely in the light of the decisions they made in life. Their lot was their choice, as it is every man’s. Placed within a moral realm ordered not by human laws, but by an inherent standard of justice, one’s merit in life lies squarely in his own hands, to rise or fall as he so chooses. For by virtue of his freedom of will, a man’s ultimate fate is his to decide and his alone.

“Expect no longer words or signs from me.

Now is your will upright, wholesome and free,

and not to heed its pleasure would be wrong:

I crown and miter you lord of yourself!”– Purgatorio XXVII.139-142

Further Reading

Probably the most readable biography of Dante is R.W.B. Lewis’ Dante: A Life. For a more detailed bio, check out Barbara Reynolds’ Dante: The Poet, the Political Thinker, the Man.

For the Divine Comedy, The Portable Dante contains Mark Musa’s translation of both the Comedy and Vita Nuova, one of the poet’s minor works. Also worth looking into is Dorothy Sayers’ translation of the Comedy, which is available in three separate volumes: Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. Allen Mandelbaum’s translation can be found online at The World of Dante, a website that also contains a collection of images, maps, and biographical information.

Danteworlds at the University of Texas at Austin is probably the best “sparknotes” version of the Comedy you can find online, while The Princeton Dante Project and Columbia University’s Digital Dante Project provide a more in-depth look at Dante’s life and writings.

[i] John Ruskin. Stones of Venice, vol. III, sec. lxvii.

[ii] Dante Alighieri. Letter to Can Grande Della Scala.