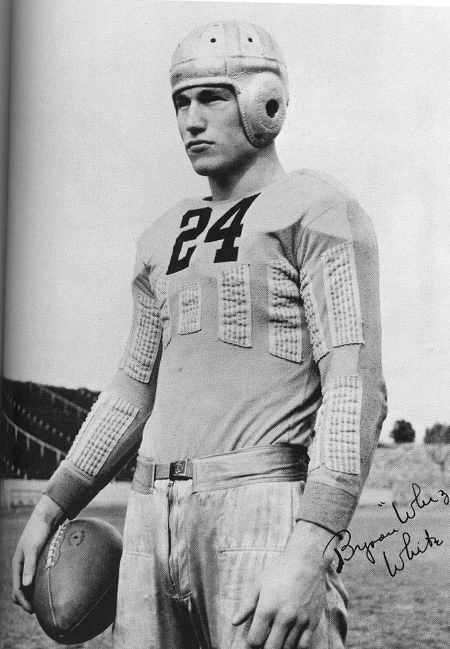

All-American halfback.

The NFL’s leading rusher in 1938 and 1940.

Rhodes scholar.

Decorated war veteran.

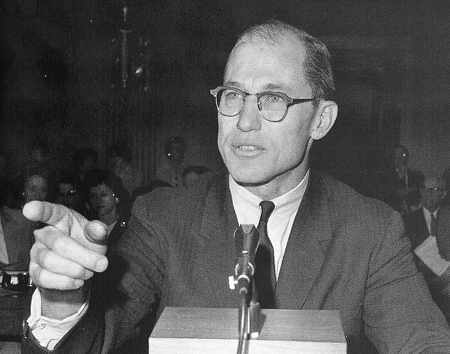

United States Deputy Attorney General.

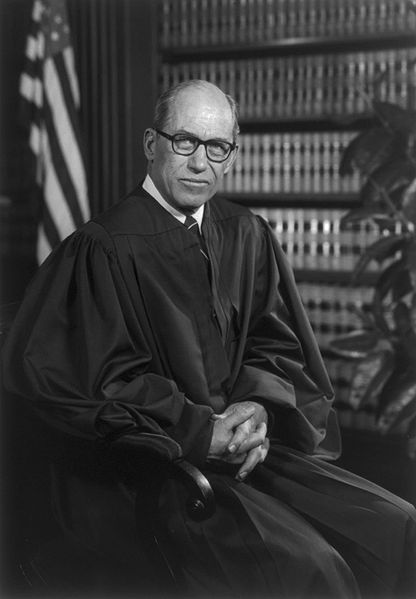

Supreme Court Justice.

History is filled with men who seem larger than life-men surrounded by an inflated myth of accomplishment, an aura that collapses as soon as one takes a closer look.

But a few men are truly just as remarkable as their billing.

Byron “Whizzer” White is such a man.

White was the epitome of the scholar-athlete, a man who excelled on both the playing field (where he earned the nickname “Whizzer”) and in the classroom.

White graduated at the top of his class in high school, at the University of Colorado, and from Yale Law School. He earned a Rhodes scholarship and became an Oxford scholar.

At the same time, he earned 7 athletic letters at CU (three in basketball, two in football, and two in baseball) and was All-Conference in every season in all three sports. On the gridiron he was a true triple-threat, and excelled at rushing, passing, and punting. He was a halfback that sometimes played quarterback, and both punted and returned punts. He became the NFL’s highest paid player and made the All-NFL team in each of the three seasons he played professional football.

“He was a man who knew himself and knew his convictions and didn’t care too much what others thought.†Ira C. Rothgerber

The son of a beet farmer, White rose from humble beginnings to an appointment on the highest court in the land, where he served for 31 years and became the fourth longest serving Justice in the 20th century. As a Justice, White was a man who stuck with his principles for his entire career. His strongly pragmatic and non-ideological approach, in which he decided every ruling on a case by case, fact by fact basis, was criticized by those who felt he lacked an overarching philosophy. Indeed, his rulings at first glance seem all over the political spectrum, but each was guided by his deep convictions on the Constitution and the role of the Judiciary; convictions he did not think could be classified in tidy boxes. He thus abhorred both “thinking by labels†and being given one. One of White’s former law clerks said:

“Being non-ideological and non-doctrinaire is clearly very important to White, just as is being his own person and not worrying about his place in history. He recognizes that being a justice who believes in a more limited Constitution is not the way to gain historical notoriety. Whether it’s because he gained such fame as a young man in sports or whether it’s just his natural disposition, I think he cares a lot more about doing what he think is right than whether it will make him a famous figure in history.â€

Lessons in Manliness from Byron R. White

“Byron White is the straightest arrow I have covered in twenty-five years. His personal integrity is impeccable, in the extreme.†-Contemporary sportswriter

Keep Your Priorities Straight

When Bryon White graduated from the University of Colorado, he was faced with an excruciatingly difficult decision: accept a Rhodes scholarship to study at Oxford or join the Pittsburgh Pirates and enter the NFL as its highest paid player.

White absolutely loved football. And for a guy who had never had too much scratch and had worked his way through life since he was a kid, the money was truly alluring.

But when it came to the value of sports over academics, there was no comparison for him. Asked about his exams for the Rhodes scholarship during an interview on his football exploits, White answered, “I don’t think such things as football and scholarships should be mentioned in the same story.â€

Sportswriter Henry M’Lemore said of White, “To him the end zone was a touchdown and nothing more.â€

And so he turned down the $15,000 offer from the Pirates to bury himself in books at Oxford.

Without even the money to pay his way across the ocean, White worked on construction crews and as a waiter in his old fraternity house to earn the dough for passage to England. He could have been earning $1,000 a week in the pros; instead he toiled for $5 a day.

Happily, after White had made his decision, Oxford and the Rhodes Trustees decided to grant White an unprecedented waiver, allowing him to play football for a year and then begin his studies at Oxford.

After a glorious year on the gridiron, the Pirates’ owner begged White to stick around for good instead of setting sail. But White knew it was time to resume his studies and entered Oxford (he would play two more seasons with the Detroit Lions after the outbreak of war in Europe forced him to return home).

Hustle, Hustle Hustle.

“He was a determined man. He had goals and he was going to accomplish them. Everything he did he was going to do to perfection. He was unique. There was never any patty-caking with Byron…It was leadership by example. He was so competitive. From the first down, he was ready to go all out.†Art Unger, CU teammate

“I hate to lose right down to my heels.â€-Whizzer White

White was surely a man who was blessed with raw, natural talent. But this potential would never have been realized if he hadn’t absolutely worked his ass off in everything he did.

All his life, White was dogged by the stereotype that a man can either be a dumb jock or a non-sporty intellectual. People found it hard to believe that a man who was so deft on the gridiron could also have a first rate mind. And so White hustled to prove them wrong.

In college he kept a strict routine from which his fraternity brothers never saw him deviate-class, football practice, job, study. “He was a brute for study,†his friends remembered. He would read his textbooks as he soaked his bum knee in a whirlpool after practice. At halftime during his games, he would be stretched out on a table with his nose in a book.

When he arrived at Oxford, his fellow students were dubious that this professional football player was a real scholar and his tutor felt doubtful that White would be able to complete his law syllabus, as he was one term behind. So White worked on his studies 14 hours a day, not even relaxing during the frequent breaks in the Oxford schedule. When White went on “vacation†with some friends to stay in a villa on the French Riviera, his roommate remembered that “Byron would be up at the crack of dawn, out the door, and running up and down a steep hill outside the villa. Then he’d come back for a big breakfast and study until dark. He studied the rest of us into the ground.â€

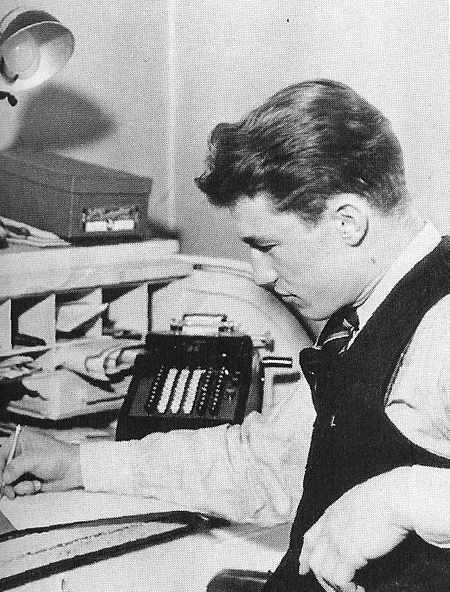

When he joined the NFL for his second season, he had to finish some classes he had started and so brought along his portable typewriter everywhere the team traveled, writing papers into the night. Each evening after dinner he would retire to his room and sit at his desk, wearing a green eyeshade and poring over his law books.

At Yale Law School, White’s fellow students, most of which came from prominent families from the East and ½ of which came from Ivy League Schools, thought that the hype around this gridiron great from Colorado was finally going to be deflated in the face of the school’s rigorous academics. Determined to prove his worth, White once more hit the books for 14 hours a day. He graduated from Yale’s Law School magna cum laude, the first to do so in ten years.

“I had never seen anyone work as hard as he did. And after practice was over, he was still out there, practicing punt returns-catching them on the fly-or kicking, and always taking extra laps.†Bill Radovich, Detroit Lions teammate

“He didn’t quit, even for one play, all day long, both ways. He was no fun to tackle, I’ll tell you. Others were faster, but listen, he was hard man to bring down. A hard man.†Sammy Baugh, Washington Redskins

White worked just as hard on the playing field as he did in the library. In college he would stay an extra 30-45 minutes after 3 hours of famously grueling regular practices working on his punt returns. In the summer he would spend hours honing his passing skills by throwing the football through a tire he had set up. To strengthen his injured knee, he spent a summer loading and unloading piles of bricks.

In actual games he went full throttle; his teammates remember him constantly playing black and blue. As a senior at CU he was the leading scorer in the country, and his record for all-purpose yards per game would not be broken until Barry Sanders came on the scene in 1988.

Yet he wasn’t an isolated, anti-social killjoy either. At CU he was elected class president, voted as the “Most Popular Man on Campus†his senior year, and chosen by his fellow students to be the “canebearer†at graduation. He traveled across Europe during his stay at Oxford (and not always with a textbook!), and later in life was involved with half a dozen community and service organizations.

How did White learn to be such a master hustler? “I just got in the habit of working,†he said. Word.

Build Your Mind and Your Body

“Byron was extremely quiet but somewhat intimidating. None of us in the room could believe how fully his forearms filled his suit coat. We all felt like wimps.†Tom Killefer, fellow finalist for the Rhodes scholarship on meeting White during the interview process.

Strength in body and strength in mind went hand in hand for Byron White, and he kept in shape religiously even when not playing college or professional sports.

At Oxford, he was barred from playing on the university’s teams because he had shed his amateur status, and thus had to look for other ways to exercise. Each Oxford student was assigned a manservant, sort of like a personal butler. White would regularly clear furniture from his sitting room and have nightly knock-down-drag-out wrestling matches with his manservant. It was an unorthodox breach of class lines, which would have gotten him reprimanded had administrators found out.

White understood that building one’s physique helped prepare both a man’s mind and body for emergencies. White’s diligence in maintaining his physique came in handy during his time in the Navy during WWII.

In 1945, a kamikaze plane bombed and crashed into the ship White was on, punching through the decks, landing in the ammo stores and plane hangar, and setting off a fire which raged all over the vessel. Gasoline in the planes ignited and ammunition was set off and fired in every direction.

Putting out the flames and rescuing men trapped by smoke and fire was the top priority. White, who had emerged from the attack unscathed, immediately went to work rescuing people and manning the fire hoses. He used his strength to lift burning beams off men who were about to be killed. White worked for four hours straight, saving every man he could, oblivious to his own safety. E. Calvert Cheston, a fellow officer remembered:

“He was absolutely focused on the fires and on the men. A shell would go off or an explosion would occur, but there was Byron-locked in on the man who needed help or on the hose that needed to be manned. I don’t think he ever thought about himself. We were all working frantically, but he stayed so cool it was almost unnerving And he never took a rest.â€

When hiring clerks as a Supreme Court judge, White would ask candidates, “What do you do for exercise? How’s your health?†People thought it was strange, even out of line, but Whizzer understood the crucial connection between body and mind.

Seek Success for Your Own Satisfaction, Not for Fame and Glory

“Byron would have been just as happy-I think he might have preferred-if he played with twenty-one other players in an empty stadium-no fans, no coaches, no referees. Football was like all sports for him-a personal challenge, a thing to test his own limits. He really hated the stuff that happened before and after the whistle.â€

“[White] was such a nice guy: you couldn’t believe that somebody with all that p.r. could be so down to earth and generous.†-Chuck Hanneman, Detroit Lions teammate

For those who knew Bryon White, perhaps the most salient characteristic about his life was not his myriad of accomplishments, but how damn modest he was about them. White was practically allergic to getting attention. Quiet, taciturn, he was a private man who loathed the press, rarely granting interviews, especially about his football career. He never wanted his football success, rather than his merit, to seem responsible for his accomplishments as a man of the law.

While playing with the Pirates, a disappointing season and scheduling difficulties left the team’s owner unable to meet the team’s payroll. Even though White would be the NFL’s leading rusher that season, he still felt he hadn’t been playing as well as he should and worried that the other players wouldn’t be paid. Although he was the highest paid player in the league, and had delayed Oxford partly for the large salary, he refused to take a paycheck for half of the season or receive any money for exhibition games even though his contract guaranteed it.

And after a dismal, losing season with the Pirates, White treated the whole team to an all-out steak dinner at a nice hotel. When asked about it later, he said the team had given the dinner.

In the Navy, the man who had been relentlessly covered in the papers from coast to coast, still kept a low-profile. Cheston said, “Byron was probably the least anonymous junior officer in the navy. Everybody had heard of him, but no one could believe how unpretentious and down-to-earth he was. You couldn’t get him to talk about his football days. He never brought it up, and if you did, he’d just shrug it off.â€

In response to his Bronze Medals, White said, “I just got in on the gravy train. The other guys really deserved the medals. I came into the squadron from a PT job in November after the biggest work was done.â€

When Justice White attended an Orioles baseball game and the owner offered to move him and his wife from the nosebleed section to his own box seats, White refused, not wanting to be seen as receiving extra perks because of his position.

It wasn’t false modesty or a show. In the words of one of his teammates, “Byron just hated ever to seem big-headed….He was just constitutionally incapable of tooting his own horn.â€

Source: The Man Who Once Was Whizzer White by Dennis Hutchinson