“In this fraternity . . . the world was divided into those that had it and those who did not. This quality, this it, was never named, however, nor was it talked about in any way. As to just what this ineffable quality was . . . well, it obviously involved bravery. But it was not bravery in the simple sense of being willing to risk your life. The idea seemed to be that any fool could do that . . . No, the idea here (in the all enclosing fraternity) seemed to be that a man should have the ability to go up in a hurtling piece of machinery and put his hide on the line and then have the moxie, the reflexes, the experience, the coolness, to pull it back in the last yawning moment-and then to go up again the next day, and the next day, and every next day, even if the series should be infinite-and, ultimately, in its best expression, do so in a cause that means something to thousands, to a people, to a nation, to humanity, to God. Nor was there a test to show whether or not a pilot had this righteous quality. There was instead, a seemingly infinite series of tests. A career in flying was like climbing one of those ancient Babylonian pyramids made up of a dizzy progression of steps and ledges, a ziggurat, a pyramid extraordinarily high and steep; and the idea was to prove at every foot of the way up that pyramid that you were one of the elected and anointed ones who had the right stuff and could move higher and higher and even-ultimately, God willing, one day-that you might be able to join that special few at the very top, that elite who had the capacity to bring tears to men’s eyes, the very Brotherhood of the right stuff indeed.†—Tom Wolfe, The Right Stuff

Tom Wolfe believed Chuck Yeager, test pilot extraordinaire and breaker of the sound barrier, to be the “most righteous of all the possessors of the right stuff.â€

But Yeager did not like the phrase himself. To him it implied that a man’s skill in the cockpit was a matter of luck-you were either born with it or you weren’t.

But Chuck knew better. He hardly discounted the luck factor in a pilot’s career, but he understood, understood better than perhaps any pilot of the time, that the “right stuff†was really attained through hard work, focus, and experience. It was not some ineffable quality that allowed him to rise from buck private to brigadier general, that allowed him to clock 10,000 flying hours in 180 different aircraft, which helped him break the speed of sound. No, it was his passion and his grit, his all-consuming love for flying and his desire to understand everything about his aircraft “down to the smallest bolt.â€

There are different kinds of manliness. There is the manliness that is quiet and subtle, that you gain an appreciation for slowly, as you spend year after year with a man. And then there is the kind of manliness that hits you upside the head like a 2X4. Which bowls you over from 40 yards away. Chuck Yeager had the latter. His life embodied the various qualities of manliness writ large.

He lived for risk and excitement and could remain as cool as a cucumber in the face of it. He did not relish killing, but found the speed and strategy of dog-fighting thrilling. He loved the structure of the military and yet from time to time would brazenly break its rules. His rebellion was rarely of the serious or sullen variety but that of a natural-born prankster who would go to great lengths for a laugh. He was fiercely competitive but never petty. He was not one for navel-gazing, but focused on getting the job done and doing it right.

He was simply the best at what he did. A flying legend. He was the first Army Air Corps pilot to become an ace in a single mission (shooting down 5 planes in one run), and would go on to become a double ace. He was selected at age 24 to attempt to break the sound barrier, leaving dozens of more senior pilots pilots shocked and jealous. But the selection paid off when he became the first to fly faster than the speed of sound.

When in-flight refueling was instituted, units of planes struggled to cross the Atlantic without errors and pilots aborting and ditching their planes in the ocean. Yeager was the first to execute a flawless trans-Atlantic deployment of a jet fighter squadron in the history of the Tactical Air Command.

And he was unsurprisingly the youngest person to be inducted into Aviation Hall of Fame.

And he did it all with the kind of style and grace under pressure that made it look easy and gave his rivals fits.

Chuck Yeager’s Lessons in Manliness

“But, like Dad, I had certain standards I lived by. Whatever I did, I determined to do the best I could at it. I was prideful about keeping my word and finishing what I started. That’s how I was raised. I never got into fights, but no one pushed me around, either.†-Chuck Yeager

Do Your Best with What You’ve Got

Chuck Yeager was not born with a silver spoon in his mouth. He grew up in a small town in West Virginia as 1 of 5 children. His family lived for a time in a 3 room house in which Chuck and his brother slept in the living room on a pull-out couch. His mom cooked cornmeal mush for breakfast, with the leftovers from that meal being fried up and served for dinner. The idea of Chuck going to college was never even considered.

Instead, when the boy turned 18, he joined the US Army Air Corps as an airplane mechanic. When the opportunity came up, he applied to become a “Flying Sargent.†Once he was accepted, he found himself in a position he would remain in his whole career-the odd man out. Almost all the other men were college graduates who would become commissioned officers.

At first Yeager was intimidated by his well-educated peers, worried he would not be able to keep up. But in the air the men were “all created equal,†and Yeager’s humble background gave him skills that compensated for his lack of a degree and quickly moved him to the head of the pack.

Everyone agrees that one of the qualities that made Yeager into a legendary pilot was his exceptional eyes. With 20/10 vision, he could see tiny specks 50 miles away from the cockpit. He saw the enemy coming long before anyone else did.

He sharpened those eyes as a boy in West Virginia. He knew how to shoot a .22 rifle by the time he was six. He would get up at dawn before school, go out in the woods, kill 3-4 squirrels, and then skin them and leave them in a bucket of water for his mom to cook up for dinner. Calm and steady, he was a real crack shot, and learned to hone in on the smallest things moving in the brush; he once shot a deer at 600 yards.

From his dad, he picked up a love and aptitude for engineering and mechanical skills. His father was a natural gas driller and would take Chuck out into the field to fix machinery and shoot wells. His father also taught him how to take apart and put back together an engine. This hands-on training gave Yeager a passion for understanding absolutely everything about how planes worked and a leg up on the competition-

Know Your Job Inside and Out

Being a test pilot was a dangerous and deadly career; little mistakes and oversights left dozens of pilots dead. There was no room for error.

Test planes were trailed by chase planes that radioed information to the pilot. But Chuck knew radio could stop working and that a situation could arise in which he’d have to make a lightning fast decision; waiting for advice could be deadly.

So Yeager wanted to know everything he could about every single plane he flew. He pored over the manual, studied the plane’s parts, and asked question after question of the flight engineers. When something went wrong at 800 mph, Yeager knew how to address it and what decision to make. He became one with the machine; he knew his plane like a cowboy knows his horse:

“Everything about airplanes interested me: how they flew, what each could or couldn’t do and why. As much as I flew, I was always learning something new, whether it was a switch on the instrument panel I hadn’t noticed, or a handling characteristic of the aircraft in weather conditions I hadn’t experienced. Unlike many pilots, I really wanted to learn the various systems of aircraft…it was a terrific advantage for me when something went wrong at 20,000 feet. Knowing machinery like I did, and having a knowledgeable feel for it, I knew how to cope with practically any problem. I knew what was serious and manageable. All pilots take chances from time to time, but knowing-not guessing-about what you can risk is often the critical difference between getting away with it or drilling a fifty-foot hole in mother earth.†-Chuck Yeager

Be Smooth

“What a character. There was just no one else like him.†-Maj. Gen. Fred J. Ascani

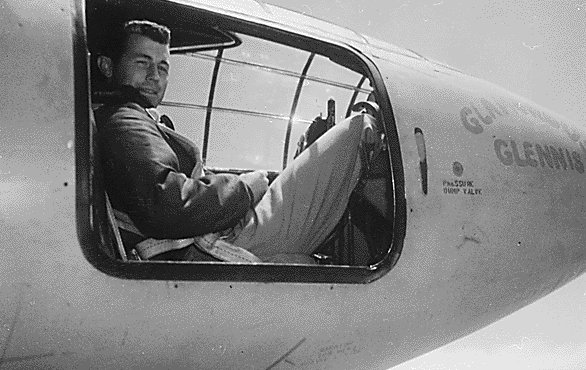

Soon after Yeager became a pilot in the Army Air Corps, he was sent to Oroville, CA for training. While stationed there, he sauntered over to the local USO office and struck up a conversation with 18 year old Glennis Dickhouse, the organization’s social director. New in town, Chuck and the other boys were in need of some entertainment, so Yeager asked Glennis to organize a USO dance for the squadron that night. Greatly annoyed with this stranger’s bold request, she asked him, “You expect me to whip up a dance and find thirty girls on three hours notice?†He replied, “No, you’ll only need to come up with twenty-nine, because I want to take you.†Sha-zam!

Yeager would soon be sent to fight the war overseas. But he named his plane “Glamorous Glennis†and wrote home to that USO gal twice a week. Glennis and Chuck would be hitched for 45 years.

Leave No Man Behind

After flying 18 missions in the war, Chuck Yeager was shot down over German-occupied France. Yeager studied the silk map that had been sown into his flight jacket and plotted an escape route over the Pyrenees mountains and into Spain.

Wounded with shrapnel, alone in an area riddled with Germans, Yeager kept a .45 gripped in his hand and slept under his parachute in the cold and rain until he was picked up by the French Resistance.

They kept him safe while the snow in the Pyrenees melted (for his part, Yeager helped them make bombs for their covert ops). When it was finally time for him to make his escape over the mountains, he was given maps and supplies and dropped off at night in the middle of nowhere. Together with other downed pilots, Yeager hiked up and over mountains, slogging through snow that was up to his knees. Ambushed along the way, the fellow pilot he was paired with was shot in the knee by a German. Only a tendon was keeping the pilot’s leg on, and Yeager sliced through it and tied off the wound.

All day and all night, in the dark, in the cold, and in the snow, Yeager dragged the wounded man up an imposing mountain. Part of him wished the man would die, but he didn’t, and Yeager would not leave him behind. Every muscle in his body was burning, and he was nearly delirious with fatigue. But he pushed ever up the mountain with the man in tow. The two pilots made it to a small village in Spain; the legless man lived because of Yeager’s Herculean effort, and Chuck was awarded the Bronze Star.

Finish What You Start

When Yeager was brought back to Leiston, England, he became the first evadee to make it safely back to Allied lines.

But the military had a rule that any man who made it back had to be sent back home to the States. They were worried that a returned pilot could be shot down again and tortured by Germans for information about the French underground.

But Chuck Yeager insisted that he be allowed to finish what he had started. The other men in his unit thought he was out of his mind, but he was determined to stay at the cold, dark base in England. Why? He felt he owed it to the military; he had not yet carried out his duty. He wanted to “make worthwhile all those hard and expensive months of combat training†the Air Corps had invested in him. He made his request to his commanding officer who told him that the rule was unchangeable and that there was nothing that could be done. But Yeager kept appealing his case up the line, all the way up until he spoke with the Supreme Allied Commander himself, Dwight D. Eisenhower. Eisenhower spoke to the War Department and granted him special permission to stay.

Follow Your Passion

“Yeager was the best. Period. No one matched his skill or courage or, I might add, his capacity to raise hell and have fun.†-Bud Anderson, leading ace of the 363rd Squadron

Chuck Yeager was good at what he did because he loved his job. He lived and breathed flying. His success followed naturally from his passion. In his own words:

“If you love the hell out of what you’re doing, you’re usually pretty good at it, and you wind up making your own breaks.â€

“I never did understand how a pilot could walk by a parked airplane and not want to crawl in the cockpit and fly off. I could not honestly claim to be the best pilot, because as good as you think you are, there is always somebody who is probably better. But I doubt whether there were many who loved to fly as much as I did. Nobody logged more flying time.â€

“I wasn’t a deep, sophisticated person, but I lived by a basic principle: I did only what I enjoyed. I wouldn’t let anyone derail me by promises of power or money into doing things that weren’t interesting to me. That kept me real and honest. Job titles didn’t mean diddly. Assistant Maintenance Officer might not be a title that would really impress Aunt Maude, but if it meant that I could fly more than anyone else, I’d stick with it for as long as I could.â€

Push on Through

“He was now involved in what was surely the grimmest and grandest gamble of manhood.†-Tom Wolfe

Some thought the sound barrier was like a brick wall in the sky, and that whoever reached Mach 1 would disintegrate upon “impact.” Other pilots had approached it but backed down from fear. As they closed in on the sound barrier, the plane began to violently shake, and it truly felt as if going any faster would rip the plane to pieces. It was at that point that pilots would get scared and slow it down. But Yeager bit the bullet and pushed on through, finding that once you “broke†the barrier, the shaking stopped and the ride smoothed out. You just had to keep going. How often is life just like that?

Be Tough

Two days before he broke the sound barrier, Yeager and his wife were racing horses in the desert at night. Chuck crashed into a gate, got thrown from his horse and broke two of his ribs. Instead of going to the base doctor, who he feared would scratch his upcoming flight, he went to a doctor in a nearby town. The doc told him to refrain from any physical activity for 2 weeks and to keep his right arm immobilized. That was Monday.

Chuck decided to go forward with the flight scheduled for the next day, telling only his flight engineer, Jack Ridley, about his injury. They decided that handling most of the controls in the X-1 wouldn’t be too bad, but that closing the cockpit door would pose a problem.

The X-1, or the “Orange Beast†as Chuck called it, did not take off on its own but was instead attached to the bottom of a B-29 and then dropped from the sky like a bomb. When it was time for the drop, Chuck would climb down a ladder at 12,000 feet and get into the cockpit. Once Chuck was inside the Orange Beast, Ridley would come down and close the door behind Yeager, who then had to reach a handle with his right arm to lock the door.

His broken ribs now made this move impossible. So he and Ridley rigged a broomstick in the handle to allow Yeager to use both arms to close it.

When Tuesday arrived, Yeager’s right arm felt useless, but he climbed in the cockpit, took off, and pushed the plane so hard he broke the sound barrier.

Experience Matters More Than Luck

“There is no such thing as a natural born pilot. Whatever my aptitudes or talents, becoming a proficient pilot was hard work, really a lifetime’s learning experience. For the best pilots, flying is an obsession, the one thing in life they must do continually. The best pilots fly more than the others; that’s why they’re the best. Experience is everything. The eagerness to learn how and why every piece of equipment works is everything. And luck is everything, too.†-Chuck Yeager

By all counts, Chuck Yeager was a lucky guy. He was born at just the right time to take part in the “golden age of flying†in the 1950s. Yeager bridged two eras-the subsonic and the supersonic. He got to test nearly all the prototypes that would develop into modern aircraft. As Yeager put it, “The old air force was being scrapped, and a new air force was being born right on our doorstep.â€

It was a time before planes became so automated that a pilot could overshoot an airport for an hour without noticing. The pilot was in control of every detail, and was more like a matador than a driver.

And when that bull was charging at him, it was experience, not luck that saved Yeager’s hide. That experience came particularly in handy while he was testing the X-1A . On this next generation of the X-1, the canopy was bolted into place; there was no door and no ejection seat. If there was a fire or a malfunction, the pilot was trapped inside.

While out on a test run, when Yeager hit a new speed record-2.4 Mach- the plane went haywire, ferociously rolling, pitching, and spinning towards the earth like a frisbee. The plane fell 51,000 feet in 51 seconds. Yeager was thrown around like rag doll in the cockpit, and his helmeted head cracked the canopy. His pressure suit inflated, the face plate of his helmet fogged over, and Yeager felt like he was a goner. But with less than a minute before impact, Yeager flipped the X-1A into a normal spin, evened it out, and landed battered but alive. Yeager said of the experience:

“To survive took everything I knew and had ever experienced in a cockpit, so that maybe one hour less flying time could have been the difference between drilling a hole or landing safely. I saved myself from sheer instinct based on hundreds of previous spin-tests. Experienced at spinning down to earth, I was less disoriented than others who had done it many fewer times, and was more likely to make the right moves to save myself.â€

At 86 years old, Chuck Yeager is still going strong, hunting, fishing, giving speeches and of course, flying. He doesn’t believe in slowing down in retirement. At age 62, he had this to say:

At 86 years old, Chuck Yeager is still going strong, hunting, fishing, giving speeches and of course, flying. He doesn’t believe in slowing down in retirement. At age 62, he had this to say:

“You do what you can for as long as you can, and when you finally can’t, you do the next best thing. You back up but you don’t give up…I know too many people who have erected barriers, real brick walls, just because they have gray hair, and prematurely cut off themselves from lifelong enjoyments by thinking, ‘I’m too old to do this or that-that’s for younger people.’ Living to a ripe old age is not an end in itself; the trick is to enjoy the years remaining. And unlike flying, learning how to take pleasure from living can’t be taught. Unfortunately, many people do not consider fun an important item on their daily agenda. For me, that was always high priority in whatever I was doing…

I’m definitely not a rocking-chair type. I can’t sit around, watch television, get fat, and fade out. And there’s so much more I want to do; I’ve never lost my curiosity about things that interest me…I haven’t yet done everything, but by the time I’m finished, I won’t have missed much. If I auger in tomorrow, it won’t be with a frown on my face. I’ve had a ball.”

Sources: