In June of 1940, the Jews of Lithuania were worried. Some had just recently fled from Poland, narrowly escaping Hitler’s reach. They had hoped to find in Lithuania a safe haven. But the Soviets had moved to occupy the country and had begun making arrests, confiscating property, and harassing the Jewish population. At the same time, the German threat still loomed. Jews felt trapped between the mouths of two gaping lions and were desperate to leave Europe in search of true safety.

But escape was no simple matter. Britain and America were unwilling to accept more than the usual number of Jewish immigrants. And even those lucky few who could secure visas to travel were running out of time; the Soviet Union had ordered the international consulates in Kaunas, Lithuania’s capital, to close. Once the consulates closed, the door to escape would be forever shut.

And so it was that on the morning of July 27, 1940, the Japanese Consul, Chiune Sugihara, looked out the window to see a great crowd of refugees pressed around the gate of the Japanese consulate. Men, women, and children, all desperate for help. They had gone from consulate to consulate without success; Sugihara was their last resort.

The crowd would force Sugihara to make a choice, one between obeying his government and obeying his conscience. What this ordinary man decided to do saved thousands of lives and imparts valuable lessons in heroism and manliness.

Lessons in Manliness from Chiune Sugihara

1. Do not be a burden to others

2. Take care of others

3. Do not expect rewards for your goodness

-The code taught at Chiune Sugihara’s school

Courage in Small Choices Leads to Courage in Big Ones

Many men wonder if they would have the courage to make the right decision in the midst of a large challenge. The answer is simple…do you have the courage to go your own way in the small decisions of your life? It is the small choices that build your courage backbone and give you the strength needed to make the right choices when truly tested.

Sugihara made the decision to follow his own path as a young man. His father strongly pushed him to become a physician. But Chiune, long interested in foreign cultures, wanted to go to college to study English and perhaps become a teacher. For years, father and son fought over this point of contention. Sugihara’s father forced him to take the entrance exam for medical school. Chiune wrote only his name on the test, turned it in, and then went outside to calmly eat from his lunchbox. Sugihara’s father was furious when he found out what his son had done. He disowned Chiune, cut off his allowance, and refused to pay for his education.

Sugihara enrolled in Waseda University to study English. He tried to pay his own way by working odd jobs, but it wasn’t enough; he was dropped from the school’s rolls. Unbowed, he took the exam for working in the Foreign Ministry. His success on the test granted him a scholarship to go to school to learn Russian and become a diplomat.

In Japanese culture, respect for one’s elders was paramount, but Sugihara had made the decision to follow the beat of his own drum, and he would continue to do so his whole life.

Sugihara was ever diligent in his studies. He would tie a pen and small bottle of ink to a rope which he looped around his ear, allowing him to take notes wherever he was. It was the precursor to the moleksine! Others laughed at his eccentricity, but when they saw he could memorize whole pages of the Russian dictionary and beat their pants off in exams, they didn’t think it was quite as funny.

After graduation, Sugihara rose through the ranks and became Vice Chief of the Foreign Ministry in Manchuria, which the Japanese had conquered and renamed Manchukuo. Tens of thousands of Chinese were murdered as part of this take over, and Sugihara, disgusted at this inhuman treatment and the Japanese military’s influence in the government, resigned his position there.

In these smaller choices, Sugihara prepared himself to make the life or death decision that loomed in his near future.

Follow Your Conscience

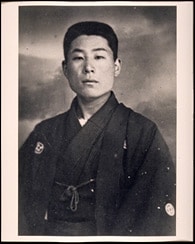

Jews waiting outside the Japanese consulate.

Jews waiting outside the Japanese consulate.

“I didn’t do anything special….I made my own decisions, that’s all. I followed my own conscience and listened to it.†-Chiune Sugihara

The Japanese Foreign Ministry eventually posted Chiune Sugihara as the Japanese consul in Kaunas, Lithuania. Issuing visas was actually secondary to what was expected of Consul Sugihara in this job; the Japanese government was interested in having him spy on what the Germans and Soviets were up to.

But then came the day when Sugihara awoke to find a large crowd of Jews waiting outside his consulate. These Jews hoped to obtain transit visas which were necessary to leave the Soviet Union and would enable them to stay temporarily in Japan on the way to their final destinations.

Unsure of how to be proceed with such a large number of applicants, Sugihara cabled the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for permission to issue the hundreds of visas which were needed. He received this reply:

Concerning transit visas requested previously STOP. Advise absolutely not to be issued to any traveler not holding firm end visa with guaranteed departure ex Japan STOP. No exceptions STOP. No further inquiries expected STOP. K. Tanaka Foreign Ministry Tokyo.

Sugihara sent another cable and received another denial. He sent another, and again his request was turned down. Some of the refugees had end visas (visas which certified that the country of their final destination would accept them), but most did not. Many also did not meet an additional requirement of having sufficient money to cover travel expenses. Some did not even have a passport. What was Sugihara to do?

The consul could not ignore the imploring faces of the people outside his gate. He consulted with wife and made the decision to disobey his government’s orders. He knew what the consequences of his action would be-he would surely be dismissed from his position when found out, and was placing he and his family in danger. The Japanese government could try and execute him for insubordination, and the Soviets and Germans could both retaliate as well. But Sugihara decided he was morally obligated to risk his future to save these human lives. He told the crowd outside the consulate that he would issue visas to each and every one of them.

Endure in Your Decision

It is easy to make a choice, harder to stick with it.

Sugihara could have issues a few dozen visas and been done with it, feeling that he had done his duty. The Soviets had ordered him to close the consulate, and now the Japanese government was also instructing him to do so.

But while Sugihara issued as many visas a day as he could, the crowd outside his consulate grew instead of shrunk. Word had spread that the Japanese consul was giving visas to one and all, and Jews from miles around journeyed to Kaunas for his life saving stamp, sleeping on the sidewalk as they waited to see Chiune. Sugihara could not turn away from them. He requested an extension from the Soviets, and they allowed the consulate to stay open until August 28th.

For weeks, Sugihara worked 18-20 hours a day issuing visas, rarely even breaking for meals. It was a painstaking process as each visa had to be written out in complex Japanese longhand and recorded in a log book. Sugihara’s tired eyes were rimmed with dark circles and his hand was sore and cramped. But the crowd did not diminish, and he continued to work. Despite the great burden he labored under, the refugees all remember his aura of kindness, how he looked at each of them in the eye and smiled as he handed them their visa.

When he was finally forced to leave, he decided he needed to stay a night at a nearby hotel to rest and gather his strength before boarding the train to Berlin. But he left the refugees a note telling them which hotel he’d be staying at, and they followed him there. He was deeply weary, but instead of retiring to his room, he sat in the hotel lobby and continued to issues visas. He no longer had his official stamps but wrote the visas anyway in the hope they’d be accepted. Stationed in the lobby, he carried on for several days until finally he had to depart for the train station. He asked those who remained for their forgiveness and deeply bowed to them.

The refugees followed him once more. As the train sat in the station, Sugihara wrote as many visas as he could, handing them out the train window to the many outstretched hands. As the train lurched forward he threw his official stationery out the window in hopes it could be put to use. As the crowd receded from view, the faces of those left behind filled his heart with sorrow.

Ten months after Sugihara left Kaunas, the Germans took over Lithuania. The Jews who hadn’t gotten Sugihara visas were almost certainly killed. From a prewar population of 235,000, only 4,000-6,000 Lithuanian Jews remained alive after the war.

Accept the Consequences of Doing the Right Thing

“Do what’s right because it is right.â€-Chiune Sugihara

Sugihara had been taught as a child not to expect rewards for goodness, and for much of the rest of his life, none were forthcoming.

Sugihara was moved to Berlin and was then stationed in Prague. There he was asked to send to Japan a full report of his work in Kaunas, including the number of visas he issued. He did not flinch from giving an honest accounting; he had issued 2,193 visas, although the number is closer to 6,000, as one visa would be given to the head of the household but would cover the entire family. He and wife anxiously waited for the axe to fall. Sugihara did so stoically, never showing his family the fear he lived with (he even continued to issue visas to Jews while in Prague).

After the war, the Soviets placed the Sugihara family in a series of internment camps before finally allowing them to return to Japan. Upon their return, the repercussions of what Chiune had done in Lithuania finally caught up with him. He was summoned to the Foreign Ministry and told that because of what he had down in Kaunas, they had no position available for him and that he should resign.

After a life of luxury as a diplomat, Sugihara was now on his own, jobless in ravaged postwar Japan. Soon after this forced resignation, Sugihara’s youngest son, who had weakened during their time in the internment camps, took sick and passed away. In short order, Sugihara had lost his prestigious position and his child. His life was spared, but for a Japanese man, the pain of losing face was absolutely devastating. Much of the buoyant warmth that had marked Chiune’s younger self seeped away.

Jobs were scarce in post-war Japan. But Sugihara did what he had to to support his family. Initially, the only job he could get was selling light bulbs door to door and working in a supermarket. The family scraped by. Later he was able to put his Russian to use, working in Moscow for a trading company. He never regretted his actions for a moment, but the consequences of those actions weighed heavily on this ordinary man.

Near the end of his life, Sugihara was recognized for his courageous decision and was named by Israel as one of the Righteous Among the Nations and visited and thanked by some of the Jews who survived the war because of his life-savings visas.

_________

Sugihara’s mother had come from a long line of samurai, and his upbringing was influenced by the Bushido code. He was taught to live with duty, honor, and dignity and to not only die bravely, but to live courageously. Because this one, single man chose to follow that code, it is estimated that 40,000 descendants of those given visas are alive today.

Sugihara may have sought to downplay the heroism in following one’s conscience, but it is perhaps the bravest, most vital thing a man can do.