Editor’s Note: This is a guest post from John Romaniello.

I want to tell you about a book that will change your life. The book isn’t new. In fact, it was published back in 1949 without much fanfare. And yet, since the time of its publication, it has made an impact that can be seen in the movies we watch, the books we read, and even the life we live.

This book has influenced thousands of writers and filmmakers in their work — but it isn’t about films or writing. This particular book has also influenced countless individuals in their own lives, helping shape them into better people, but it isn’t a self-help book. It is a book about stories, and storytelling — the stories that drive our societies, and the way we tell them. And because of the commonalities of those stories, it is very much a book about us, and the way we view the world.

More importantly, it’s about how we can become better men. The book is about self-actualization at its core and has a replicable approach that applies to every man.

The Hero with A Thousand Faces, by Joseph Campbell, is ostensibly about myths and mythology. But the lessons in this book can help us identify and navigate the paths we take to better ourselves and the changes in our lives, in order to become better at change, and better people in general.

Campbell, a professor at Sara Lawrence College, studied lore from every conceivable culture; he looked at everything from the ancient religions of antiquity to the mythology of more modern religions like Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.

Campbell’s research led him to focus on comparative mythology; specifically, he looked at what myths from different cultures had in common, rather than what they didn’t. Everywhere Campbell searched, he found it: a single story-telling arc, the ubiquitous story that every culture from Mesopotamia to our modern Western Society uses to pass along information, tradition, and worldly perception. Collectively, Campbell put this information into his seminal and most influential work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

Borrowing a term of James Joyce, Campbell called this universal pattern the monomyth. You might know it as the Hero’s Journey.

It is a single myth, told in a thousand different ways; a single hero, with a thousand different faces. The monomyth is in every story you’ve ever heard, most of the movies you’ve ever seen — and it’s present in your own life, every day. And understanding it can make you a better man.

The Hero’s Journey and Why It’s Important

The monomyth begins with the main character, or Hero, in one place, and ends with him in another — both physically and emotionally. Campbell asserts that this Hero is the same regardless of the story, and that he appears in different forms. This is important because the hero can be the star quarterback or he can be the accountant in cubicle nine. The paths are different but the journey is the same.

Within each journey, the Hero will encounter other characters that play an essential role in growth. Campbell labeled these archetypes (the Herald, the Mentor, the Goddess, the Trickster, etc.), and they appear in the vast majority of stories. It’s easy to spot an archetype once you know what you’re looking for. So whether the hero is Harry Potter or King Arthur or Frodo, his path is always very similar. Whether the mentor is Dumbledore or Merlin or Gandalf, his role is always to guide the hero.

This structure appears everywhere, but is most easily recognized in movies and books. Luke Skywalker starts his journey by leaving his home on Tatooine, having grand adventures, and fulfilling his potential as a Jedi. The events might be different, but the journey is the same one King Arthur takes. And this is the same exact course that prominent figures in religious stories all follow. Campbell shows us just how accurate this concept is, and how it replays over and over again. And it’s happening right now in your life, too.

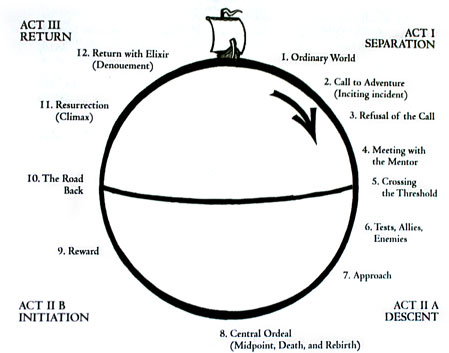

Not yet convinced? Okay, let’s break it down with some examples and let’s take a look at the steps of the Hero’s Journey. While Campbell’s model is 17 stages, for the sake of brevity, I prefer the more abbreviated version used by Christopher Vogler in his book The Writer’s Journey.

Vogler’s model of the Hero’s Journey.

Now, looking at that picture, as well as chart below, you’ll probably get a good idea of what each stage signifies based on the name; the examples will drive home that all of this is applicable to every story you have ever heard.

Stage of the Journey | Description | Example |

| The Ordinary World | The Hero’s starting point | Dorothy Gale living on her farm (The Wizard of Oz) |

| The Call to Adventure | The Hero realizes that there is a larger world that he can be a part of | Harry Potter gets a letter from Hogwarts (Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone) |

| Refusal of the Call | In a moment of doubt, the Hero decides not to undertake the quest | Luke Skywalker tells Obi-Wan Kenobi that he can’t go to Alderaan (Star Wars) |

| Meeting with the Mentor | Either the first encounter with the Mentor figure, or the moment when the Mentor encourages the Hero to take on the Quest | Daniel LaRusso meets Mr. Miyagi (The Karate Kid) |

| Crossing the First Threshold | The Hero moves from the Ordinary World to the Special World, and sees the difference between the two | The Narrator walks into Tyler Durden’s house for the first time (Fight Club) |

| Tests, Allies, and Enemies | The Hero begins to undertake tasks that will help him prepare for the road ahead; he also meets friends who will aid him, and foes who will try to stop him | Frodo leaves Rivendell with the Fellowship of the Ring, and has to learn how to be on the road as he goes (The Lord of the Rings) |

| Approach | Internal and external preparation; usually includes an imposing destination | Neo and Trinity gather an arsenal before heading off to rescue Morpheus (The Matrix) |

| The Ordeal | The central conflict in the story, the big boss fight, where the possibility of death is imminent | Dorothy and her friends battle the Wicked Witch in her castle (The Wizard of Oz) |

| Seizing the Sword/Reward | Having slain the enemy, the Hero is free to take the treasure; sometimes this is an item of great value, like the Holy Grail, or a person, but very often it’s something more abstract, like the end to a war | After the death of the dragon Smaug, Bilbo and the dwarves are free to help themselves to his treasure (The Hobbit) |

| Apotheosis and Resurrection | Often, the Hero needs for all of his growth to come to a head and manifest itself all at once in a moment of enlightenment called apotheosis; this realization is the death blow to the old self and beliefs, and the embracing of the new; this is punctuated by a symbolic (sometimes literal) death and resurrection | The Narrator realizes that in order for him to stop Tyler Durden, he must kill himself — by making peace with his own death he accepts mortality, and is, for a moment, truly at peace; he shoots himself and lives, though Tyler is dead (Fight Club) |

| The Road Back | The Special World, with all of its lessons and adventures, may have become more comfortable than the Ordinary World, and for some Heroes, returning can be harder than the initial departure. | After the One Ring is destroyed, Frodo has a hard time adapting to life as a normal Hobbit in the Shire (Return of the King) |

| Return with the Elixir and the Master of Two Worlds | The Hero returns home changed, and uses the gifts he received and lessons he learned on the journey to better others; at the same time, the Hero must come to terms with all of the personal changes he’s undergone; he must reconcile who he was with who he has become | Luke, now a Jedi, restores balance to the Force, helping bring peace to the galaxy; concurrently, he is able to resolve his relationship with his father and move on (Return of the Jedi) |

But Campbell’s thesis is not simply that nearly every culture in history has found an identical and effective way to tell stories; it’s that the commonalities in storytelling exist because they are a fundamental part of the human experience. The monomyth isn’t only the structure of how we tell the undertakings of heroes and characters in stories, it’s also how we relate those stories to ourselves, and, in a very real way, how we understand the things that are happening to us.

I would take it a step further.

I believe that while the monomyth is exceptional for storytelling, and therefore exceptional for exploring cultural ideas, it can have just as great an impact when applied to an individual — when applied to you. Put somewhat more directly, the Hero’s Journey is the perfect lens through which to view any change in your life — whatever new journey you’re taking, you will go through all of the phases of the monomyth as you grow, adapt, and ultimately fulfill your goal.

Of course, I’m not the only one who suggests this. For years, the Campbellian model has been used by people in various fields to help people advance; for example, some therapists use it with their patients to help structure psychoanalysis. Similarly, it’s used to help people deal with the grieving process — after all, the 5 stages are grief each have their mirror in the monomyth. Still others use it for mindset or success coaching — helping people understand where they are in the journey not only provides a sense of comfort and control, but also a clear path, making it easier, conceptually, to get to the next phase.

Because all changes in your life can fit into this structure, whether you realize it or not, at any given time you’re going through at least one such journey — and mastering the ideology of the monomyth will make you more successful. Because not only is the Hero’s Journey a lens for viewing change, but it’s also an excellent operating thesis for propelling change forward.

Practical Application – the Journey of a Gym Rat

My exposure to Joseph Campbell and to the gym came at roughly the same period of time in my life. I was a sophomore in college and in need of massive changes to my mind and body. I was 25 pounds overweight, clinically depressed, and generally just unhappy. An inauspicious beginning to my tale, but true nonetheless. That year, I was assigned to read The Hero with a Thousand Faces in a class on Utopian/Dystopian literature. Within the first 30 pages, I was hooked.

At that point, I certainly didn’t think I’d found a problem-solving methodology, but being a guy who was heavily into medieval fantasy and mythology, Campbell spoke to me as a storyteller. Reading Hero was immediately beneficial: it made all the books I was already reading even more accessible, and enjoyable. (And believe me, at 19, it was hard to imagine anything that could make re-reading The Lord of the Rings for the eighth time even more enjoyable — Hero did.)

Around this same time, I entered a gym, underwent a massive physical transformation, and changed my life in a number of ways. Not only did I build an impressive physique that opened a number of professional doors from fitness modeling and personal training to writing, but I also learned a variety of lessons that have carried over to every aspect of my life, and became successful in ways I couldn’t have imagined.

It might seem a little silly to think that getting fit helped me do better in school and have better relationships, and sillier still that it eventually allowed me to start my own business, live life on my terms, and even write a book. But it’s all true.

Perhaps more importantly, my transformation, and the lead up to it, was a step-by-step retracing of the Hero’s Journey. As I said, all changes can fit into this model. Let’s take a look at mine.

The Ordinary World – I was fat and depressed, but didn’t know much else. Like Harry Potter under the stairs or Frodo in the Shire, my Ordinary World was my everyday life.

The Call to Adventure – In my case, it was an actual phone call. At this point in my life, I was working in a retail store (Gap, of all places), and a woman called asking me to have 30 white polo shirts ready for her when she walked in. Long story short, it turned out her husband was opening a gym about 5 minutes from my house. At the moment, I wanted to make a change. Now, “I need 30 white polo shirts,†isn’t quite as dramatic as “Help me Obi-Wan Kenobi; you’re my only hope,” but it got the job done.

Refusal of the Call – Change is hard. Sometimes the Hero is more afraid of change than they are of continuing to be unhappy in their situation, or body. The majority of the people who want to embark on a fitness journey (or any journey, for that matter) never get past this point; they think it will be too hard, or that they can’t change. Or, they start and simply give up. In my case, although I was interested in changing, I was nervous, and it took a few days before I mustered up the resolve to go check out the gym.

Meeting with the Mentor – Heroes can’t do everything on their own; we all need mentors. When I finally walked into the gym, I met the owner, Alvin. He had an encouraging manner and an inspiring physique. I took to him immediately, and let him guide me. When it comes to changing your body, that mentor doesn’t necessarily need to be a person with whom you have direct contact; the role of the mentor can also be filled by a book or even website. The author will help you without ever meeting you.

Cross the First Threshold – Threshold crossings happen throughout journeys, and the first is always the most impactful. It’s what separates the Ordinary World from the Special World. When I first joined the gym and started reading about fitness, it was like Dorothy stepping into Oz; there was so much to take in it was intimidating.

Tests, Allies, Enemies – As I began on my transformative journey, I quickly realized that there were people who wanted to help, and people who didn’t. Some people will support your fitness goals and avoid tempting you; others will call your goals silly and vain. Every time I went to a party or dinner, I had to deal with the invariable, “Just have a bite,” or, “Just one drink.” These things are tempting, but to make my transformation a reality, I had to pass these tests.

Approach – As I prepared for the final showdown — the real meat of the transformation — I had to arm myself to go through it. There were a lot of small events during this time — cleaning out your fridge and throwing all the junk away, restocking with healthy food, mastering proper exercise form, and learning about nutrition.

Central Ordeal – The Ordeal is about the act of change, and the necessity for it. As it applied to changing my body, this was the actual transformation program — that 16-week period where I focused ardently and made it my goal to bend my body to my will. Metaphorically, the Ordeal is about the war between the light and dark halves of your psyche, and your attempt to balance them.

Apotheosis/Resurrection – Anyone who has gone through a major transformation understands that the results of the Ordeal are pretty intense. In almost all cases, you achieve a sense of heightened awareness — not necessarily supreme enlightenment, but, at the very least, an unveiling of a world or experience previously hidden from your eyes. In my case, this was the realization that being fit was possible for me, and that all of the benefits of being in this “club” were mine. As a storytelling device, apotheosis is about becoming godlike, at least for a moment; in most cases, this only occurs when the character sets aside all resistance and fully gives in to the experience. In that moment, you will not be a god, but you will be like a phoenix — your new, better self rising from the ashes of the old one you’ve left behind.

Seizing the Sword/Reward – This is what you get after the battle — something for you. It’s when the heroes gather together and say, “Wow, look what we’ve done.” It may be a celebration, or a love scene. For me, it was an increase in self-esteem and health that accompanied my new body. Much more than that was the belief in myself that I could manifest change; I’d done this thing which I previously thought impossible, which instilled in me an unshakeable belief that I could do just about anything.

The Road Back – After the battle itself is over, the Hero must return home. This is sometimes more difficult than leaving in the first place. The Road Back is emotionally trying, because you fear that you’ll lose what you gained on the quest. In my case, I had some trepidation that once I was no longer in the throes of focusing on a transformation, I’d revert back to my former self.

Return with the Elixir – In the best of cases, Rewards are not just for the Hero, but also for everyone around him. Frodo destroying the One Ring brought peace to Middle-Earth; Harry Potter destroying Voldemort did the same for the wizarding world. Well, my transformation sadly didn’t end any wars or save the world, but it did help a lot of people. The act of changing helped me become a better version of myself; many of my better qualities were amplified. I was happier, and made other people happier; I was also more helpful, more dedicated, and (strangely) more punctual. My transformation also inspired others to take journeys of their own. More than anything, the knowledge that I’d gained over the years — starting with when I made my own transformation — allowed me to become a coach and author, helping first hundreds, and eventually thousands of people change their lives.

Master of Two Worlds – The last stage of the journey is when the Hero becomes the Master of Two Worlds — he is able to unite the light and dark within him. Metaphorically, this stage is about balance — about reconciling who you were with who you have become, and allowing yourself to accept both. For me, it was about mastering life in my new body — understanding all of the benefits it provided without going overboard in any direction. This was a continuation of the Road Back, and was about slowly moving away from the more extreme stuff and finding a way to live life and do things that normal people do, like go to dinners and have the occasional beer.

I should mention that at the time I made my fitness transformation, I didn’t realize that I had been on what could be called a Hero’s Journey — my familiarity with Campbell was fresh, and I wasn’t able to see the parallels quite as clearly. It wasn’t until I began my business (Hero’s) Journey that I understood that Campbell could be applied to anything. From that point on, I began to incorporate some aspects of the monomythic structure into my client’s programs and my lessons with them; I found that teaching Campbell helps teach fitness information, or at least drive the point home. And it was from this general understanding that I wrote my book, Man 2.0: Engineering the Alpha. And I used that platform — a book that become a New York Times bestseller — to show how to use the Hero’s Journey to get in the best shape of your life.

Outside the Gym: Other Examples, and How Campbell Affects You

Of course, a fitness journey is just a single example of how the monomyth can be applied to your life. Once you know the general structure, it’s not difficult to plot journeys in all aspects of life — everything from your decision to enroll in college to your romantic relationships.

It has exceptional validity with regard to love, actually — just look at the standard plot outline of a romantic comedy: boy meets girls, boy loses girl, boy gets girl back, could just as easily be boy hears the call to adventure, boy refuses call to adventure, boy goes on adventure anyway. In either case, through the assistance of a mentor (could be a wise-cracking friend or parent figure), the Hero will go on a journey of introspection and come out on the other side worthy of the girl.

A more detailed example might be that you get married, and settle into married life (Ordinary World). Your wife gets pregnant (Call to Adventure). You freak out at first (Refusal), but are obviously thrilled. Over the course of the pregnancy, appointments with your doctors (Meeting with the Mentor) help you and your wife (Allies) prepare (Approach) for the birth of the child (Threshold Crossing). Being a parent is now your main responsibility (Ordeal) and at the end of the quest there is your child — your legacy — who will carry on in the world after you’re gone (Return with Elixir).

Want a professional example? How’s this: you lose your job (Call to Adventure), and although you feel its loss and want it back (Refusal of the Call), you eventually decide that you want to move on to a new career. This can go in any number of ways, let’s assume you seek the help of a business coach (Meeting with the Mentor). Eventually, you decide to start your own business, or start a blog — something you’ve never done before (Crossing the First Threshold). There are a lot of challenges along the way, as well as successes and failures (Tests, Allies, Enemies). Follow this path to its ultimate conclusion and you wind up creating something — income, a book, a product — (Reward) that betters you (Apotheosis) and allows you to better the world (Return with the Elixir).

Closing the Circle

While the strength of the monomyth is certainly due to its universal applicability, perhaps the greatest benefit comes after it’s been applied. As I alluded to above, the act of change itself changes you.

This principle is what allowed me to take the next step in my own journey and write Engineering the Alpha as a way to make the journey relevant to all men and help them see the path that could guide them to their biggest goals — whether physical, emotional, or social. The result has been a testing ground where thousands of men have been able to transform their lives in ways they never thought possible.

And it’s all because of Campbell. Understanding the Hero’s Journey is comparable to the moment when Neo understands the Matrix. It allows you to comprehend what is happening and why, and exactly how you should respond and react to make the best decisions possible. Life slows down, and when that happens you can speed up and make better choices that ultimately lead to change.

By going through a massive change, you will come to a greater understanding of yourself, and what you’re capable of. Success is a learned habit, and success begets success — the more positive changes you go through, the less resistant to change and growth you will be.

All that’s left is one simple question: Are you ready to become the hero? If so, it’s time to recognize your ordinary world, begin the journey, and ultimately become a better man and the best version of you.

Where are you in the Hero’s Journey? Let us know in the comments!

__________

John Romaniello is an angel investor, coach and nerd living in NYC. When he’s not rambling about the influence of the monomyth on comic books or the cultural importance of Star Wars, he spends time helping people change their lives and bodies. His new book, Man 2.0 Engineering the Alpha: A Real World Guide to an Unreal Life (HarperCollins), debuted on the New York Times bestseller list, with a follow-up in the works.