The Sultan of Swat. The Colossus of Clout. The King of Crash. The Great Bambino.

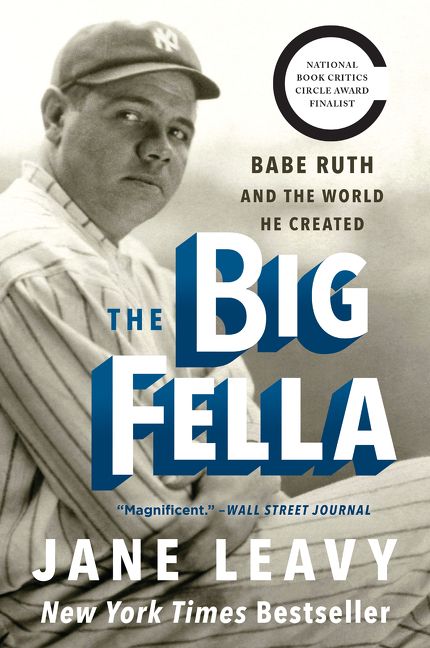

Babe Ruth died over 70 years ago, but his legend still lives on in big league stadiums and little league fields across America. While we know a lot about Ruth’s baseball career, little was known about his early life and how it shaped him to become America’s first superstar athlete and celebrity. My guest today sought to remedy that in her recently published biography: The Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the World He Created. Her name is Jane Leavy, and she’s a former sports journalist and the author of two other biographies of baseball greats. We begin our conversation discussing Ruth’s sad and difficult childhood in a Baltimore boarding school and how he learned to play baseball from the Xaverian brothers who ran it. We then shift to how Ruth’s hunger for affirmation helped him become the country’s first real celebrity, and how his baseball career coincided with the burgeoning fields of public relations and technology, ushering in a new era in sports writing, endorsements, and entertainment. We end our conversation discussing Ruth’s legacy in the world, and business, of professional sports.

Show Highlights

- Why Jane decided to write a new biography of Babe Ruth

- Babe’s destructive childhood

- How Babe got into baseball

- Ruth’s relationship with Christy Walsh (the first sports agent)

- The mass media revolution and how people consumed sports

- The legend vs. reality of Babe Ruth

- How Babe’s improprieties were finally exposed

- “Gee whiz” journalists vs. “Ah nuts” journalists

- Babe Ruth as husband and father

- Ruth’s response to getting cancer

- How did Babe change baseball? Why are we still fascinated by him?

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Babe by Robert Creamer

- Bob Feller

- Christy Walsh

- 15 Best Baseball Movies

- How to Catch a Souvenir Baseball

- 7 Pitching Grips Every Man Should Know

- How to Break in a Baseball Glove

- Scoring a Baseball Game With Pencil and Paper

- Grantland Rice

Connect With Jane

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Recorded on ClearCast.io

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

The Athletic. Sports coverage that goes beyond game recaps to provide smarter analysis and a deeper perspective about teams and leagues. Go to theathletic.com/art to get 40% off your subscription.

Saxx Underwear. Game changing underwear, with men’s anatomy in mind. Visit saxxunderwear.com/aom and get 10% off plus FREE shipping.

The Great Courses Plus. Better yourself this year by learning new things. I’m doing that by watching and listening to ​The Great Courses Plus. Get a free trial by visiting thegreatcoursesplus.com/manliness.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. The Sultan of Swat. The Colossus of Clout. The King of Crash. The Great Bambino. Of course, I’m talking about Babe Ruth who died over 70 years ago, but his legend still lives on in big league stadiums and little league fields across America. While we know a lot about Ruth’s baseball career, little was known about his early life and how it shaped him to become America’s first superstar athlete and celebrity. My guest today sought to remedy that in her recently published biography: The Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the World He Created. Her name is Jane Leavy, and she’s a former sports journalist and the author of two other biographies of baseball greats.

We begin our conversation discussing Ruth’s sad and difficult childhood in a Baltimore boarding school and how he learned to play baseball from the Xaverian brothers who ran it. We then shift to how Ruth’s hunger for affirmation helped him become the country’s first real celebrity, and how his baseball career coincided with the burgeoning fields of public relations and technology, ushering in a new era in sports writing, endorsements, and entertainment. We end our conversation discussing Ruth’s legacy in the world, and business, of professional sports. After the show is over, check out our show notes at aom.is/ruth. Jane joins me now via clearcast.io. Jane Levy. Welcome to the show.

Jane Leavy: I’m so glad to be doing this.

Brett McKay: You got a new biography out about Babe Ruth. It’s called The Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the World He Created. There’s a couple of biographies about the Babe out for the 70 years since he’s died, even while he was alive, people writing biographies about him. Why did you think the time was right for another biography about Babe Ruth?

Jane Leavy: Truthfully, I didn’t think the time was right for another biography of him. It was the last thing I wanted to do. In part, because there have been so many biographies of him as you mentioned, starting back when he was still alive. I think the first one was Ghost in 1928 and that was an autobiography obviously. But the guys who came before me and most notably Rob Creamer, who wrote Babe in 1974 and there was a whole constellation of books published then, because it was just as Henry Aaron was approaching Ruth’s career home run records 714. They all did in some way, a really, really good job.

But when I sat down and read all of those books, which I did before actually signing a contract and agreeing to do this, what was most notable was the omission of his entire childhood. Now, sports biographies have always been a kind of sub genre. You wouldn’t be able to write a biography of Winston Churchill or Franklin Delano Roosevelt and leave out the first 20 pages, excuse me, first 20 years of his life, but in sports you could, because most sports biographies were what Mickey Mantle used to call all that Jack Armstrong shit. They were hey geography and they were often written for children, and they weren’t just biographies of sports careers not of sports lives. The guys who came before me did an estimable job in reconstructing his career and reconstructing day by day on the field, his exploits in every which way, but they couldn’t really get at the whole person.

Once I established for myself that there was a hole that I might be able to fill, then I had to persuade myself that there was a way to fill it. I started the way most biographers do, by making a list of anybody alive that I could still talk to and of course, that was another inhibition. Everybody that Babe Ruth basically knew or was close to is presently dead. But at the time that I started this, which was back in 2011 or 2012, his daughter, Julia Ruth Stevens was still alive. She was a perky 95 or 96 years old, I’m not sure which. I went to visit her at her family home in New Hampshire and apropos of nothing that I can claim to have instigated in any smart way.

She suddenly leaned over to me and said in a very kind of prude way, “You do know that George Herman Ruth Senior, in other words Babe’s father and Katie, his mother, were separated.” She actually sort of whispered it in a confidential way and I looked at her, my jaw dropped. I looked at her, I said, “No, I did not know that.” Frankly, nobody knew that. I called up, then, one of his granddaughters, a daughter of his other daughter, now deceased Dorothy, and I said, “Julia said the most amazing thing.” She said, “Oh hell, they weren’t separated. They were divorced.”

There’s the moment for a reporter, you just go, “Uh-ha. Now I see it.” Because to come from a family that was as chaotic, violent, and as destructive as his was, that ended up in a divorce, which was publicized at the time in the hometown papers. George Herman Ruth Senior’s divorce from Katie made news in the Baltimore Sun and the Baltimore American in May 1906. But when Babe Ruth was alive and playing and being asked questions, which I assume he was asked to some extent, about where he came from, about his parents. That wasn’t something you talked about. There were no 20 minute segments or 60 minutes in which to air ones personal history and gather sympathy for having triumphed over them. Babe Ruth kept it quiet. He never, ever, ever talked about where his family was, where they came from. He never answered any questions. I hoped going into it that if I could fill in that hole and find the boy that his family called little George, I might be able to explain the relationship between little George and the big fella that he became.

Brett McKay: That’s the big idea in your book.

Jane Leavy: Yes.

Brett McKay: To understand Babe Ruth, you have to understand his childhood. It’s interesting because there’s sort of… because babe didn’t talk-

Jane Leavy: I think Froid would say this by the way.

Brett McKay: Fred. Fred.

Jane Leavy: By the way, yeah.

Brett McKay: But yeah, Babe, he’s never talked about his childhood, there’s sort of these myths that he was an orphan, and that he didn’t have any parents or his parents died. But as you said, that wasn’t the case.

Jane Leavy: No. In fact, what happened was this, the divorce was ugly and the causes that were stated in the Baltimore Sun for granting this divorce to George Senior were adultery and drunkenness. All I had to do, and this doesn’t make me a great reporter, it makes me a lucky reporter, was go into the archives of the Maryland… Maryland State Archives and type in the words, George Herman Ruth V., I contributed the V Katie Ruth and up popped a 150 page dossier with all the depositions, police reports, et cetera, et cetera, revealing just again how chaotic, violent and destructive this family and this disintegration of the family was. George Senior according to his testimony in the divorce, found his wife on the quote dinging room floor with one of his bartenders, George Ruth having managed or owned several bars around Baltimore in Babe’s time.

Who was going to talk about that? You didn’t talk about that in 1906 or 1920 or 1927 when Babe Ruth hit 60 home runs and he’s King of the world. You just didn’t say it out loud. Today everybody gets divorced, right? Big schmeer but back then, no. The reason that he was sent away was speculated upon forever since he wouldn’t ever say what really had happened. People came to two conclusions. One was that he was an incorrigible, which was a legal term used back then to describe boys who got in trouble with the law and who were sent by the courts to a quasi-public institution, in this case, St. Mary’s industrial school for boys, which was a school that sat outside the main downtown of Baltimore on the cusp of Baltimore city, and where they accepted incorrigibles as they were legally defined, they also excepted wayward boys, abandoned boys, orphaned boys and boarding students.

I’ll often go around groups when I talk and say, “Which do you think babe Ruth was?” Everybody else raised their hand saying, “Oh, he was bad kid. He was, you know, he was stealing stuff on the waterfront. He was getting in trouble with the law.” Other people raise a hand, say, “Oh no, no. He was an orphan.” They’d say, “St. Mary’s was an orphanage.” Well, yes, they took some orphans, but they were not primarily an orphanage. In fact, Babe Ruth was a boarding student and his father paid for him to live there and never bothered to go visit him once, by the way, in the entire time that he was living there. The boys thought of themselves as inmates. There really was no place else for them to go. There were not big fences and guys with guns on the roof, as has often been written, but it was not a warm and cuddly atmosphere.

It was to Babe Ruth’s advantage to allow people to conclude two completely opposite and erroneous things about him rather than to tell the truth. Even a reporter from St. Louis said to him in 1929, “Well, you’re an orphan, right Babe?” He got really angry, and he would pound his fist on the table and say, “No, I had parents.” But he would never go further than that. “Oh, you were a really bad kid.” “No, I wasn’t a bad kid. Ask the brothers at St. Mary’s.” The Xaverian brothers, a teaching order that ran the school, but he never filled in the gaps. The myths proliferated and became set in Amber, and he couldn’t escape them after a while. He didn’t really have much interest in doing so.

Brett McKay: What I thought was interesting of this book is it’s not a life-to-death narrative of Ruth’s life. Rather, what you do is you take this barnstorming tour that Ruth and Lou Gehrig did after the 1927 baseball season, and use that as a jumping off point to explore different parts of Ruth’s life. First, talk about what this barnstorming because I didn’t know that this happened back in the ’20s in professional baseball. What that is, and then why do you use this as the narrative framework for Ruth’s life?

Jane Leavy: Sure. Barnstorming, which is of course an aviator’s term. It’s what you used to call it when aviators in the early years, like Lindbergh would fly in and out of cities in small planes delivering mail and things. Barnstorming was a long time tradition for ballplayers who of course didn’t make a lot of money back in the day, to make extra money during the off season and they would organize teams sometimes around a couple of stars. There was for a while a Babe Ruth all star team, but even Bob Feller had a traveling barnstorming team in the ’40s. It was a tradition. What I wanted to do was get Babe Ruth out of the city. I wanted to be able to give a portrait of him at the apex of his career. This tour in 1927, organized by his agent Christy Walsh, was almost a victory lap of the country.

It starts just 10 days after he’s hit his 60th home run and they go caravanning from town to town, to town and playing essentially, not quite pickup games, but they play baseball games against sometimes a minor league team or a semipro team. Remember there was a lot of baseball talent in America, and people played in organized leagues. They would collect money wherever they went.

Christy Walsh, who was very, very savvy, made sure to get the money upfront and when they didn’t get the money upfront one time in his very park, Babe and Gehrig’s sat in their underwear in a hotel suite at a hotel waiting for somebody to come up with the cash. What this did was allow me to show Babe Ruth at the absolute apex of his fame, and to show what it was like to be him and to be around him. That, you didn’t really get in the New York papers because New York writers basically didn’t write what he said, they often made it up or they just didn’t quote them at all. But the local reporters for whom this was a once in a lifetime event, that Babe Ruth was coming to their town, wrote down every detail of what they said, what they did, who they got an award from, what the woman was wearing who gave them the award, you name it.

It was a gold mine of information that could give you a flavor of what it was like to be him. Because to be Babe Ruth in 1927, was to be the first really great modern celebrity. I would say and I think I did say, he was the most famous man in America who wanted that fame. Lindbergh obviously, who had crossed the Atlantic in the spirit of St. Louis that year, he was as famous certainly, but he didn’t really want to be. He liked being up in the sky, away from the press in the flesh. Babe Ruth, the little boy who was sent away to an institution at age seven where he learned how to be public, he lived in dorms with boys, always slept head to toe and rose beds that were separated by just a bent wood chair. He was never alone as a kid.

What he learned as a little boy, and this was the revelation for me, what he learned was how to be public. He learned to be comfortable surrounded by a mass of male energy. With the pictures you see of him, and one especially taken in Syracuse in 1925 during a Yankee off day. They played an exhibition game there, where 5,000 boys tried to cram themselves into a single frame with the Babe and they’re draped over him like a cheat for Boa. They can’t get enough of him, and more to the point he can’t get enough of them.

Brett McKay: Babe wanted to be famous. Did he start playing baseball so he could be famous and be a celebrity? Or did he have a talent for baseball that people recognized and he became a celebrity and then he’s like, “That feels good,” and just did more to foster that?

Jane Leavy: Baseball was an organizing principle at St. Mary’s. They had all chronically overcrowded place, and the way they could channel all that energy was to organize leagues and teams. Whenever they weren’t in the classroom, and they weren’t in the classroom all day, the way kids are today or would have been in regular schools. They send them outside morning, noon and night, spring, summer, fall and winter to play baseball. He had… It was almost like a farm system for growing baseball talent. He stood out from the beginning, partly because he was bigger than everybody else. Later in his time at St. Mary’s, people would assume that he was a staff member because he was so much bigger than everybody else.

There was a system of athletics there and people who really knew the game and had to teach it. The one who is most often credited with having turned him into the ball player he his was a guy named Brother Matthias, who was a kind of a mythical giant, depending on who you believed. He was 64’66, and 225 or 250. He certainly was there, and he certainly had a lot to do with the Babe, but he wasn’t the only one. There were a couple of other brothers who knew their stuff out on the ball field and he was given an opportunity to shine. This was a kid who needed to shine and who wanted the attention that clearly he wasn’t getting in any other way. At St. Mary’s, you got visitors on a Sunday once a month. One of the few remaining accounts of his life there, a friend of his wrote that another Sunday came and went and they’ve had no visitors and he said, “I guess I’m just too big and ugly to visit.”

This was a kid who needed and wanted attention, and what better way to get it than by throwing a ball further and harder than anybody else could. Because of course, first he was a pitcher as we all know. He didn’t set out to be famous. That kind of fame didn’t exist in certainly in sports. Remember when he was a rookie with the Boston Red Sox in 1914 having been mustered out of St. Mary’s by Jack Dunn, owner of the minor league of Baltimore Orioles, and then sold just six months later to the Red Sox. Fame was a local thing. It was the circumference of the distribution of the local newspaper where, as far as a newspaper boy could hurl the morning paper, there was no radio there. What you learned about famous acts and things after the fact. One of the fascinating things about Babe’s life is to look at it in terms of how much the country changed. Felicitously for him, it changed so profoundly in a kind of revolutionary moment in the ’20s just as he was assuming that full height of his powers.

Brett McKay: There were people in Babe’s life that were facilitating this change in modern America. You mentioned one of them, Christy Walsh, who was sort of his manager. This is the thing, you said Babe Ruth created a whole new world that didn’t exist before him and something that didn’t exist really at that time before him were a sports’ manager or an agent or a PR person. Christy Walsh was kind of all this in wrapped up into one. Tell us about him and his influence in Ruth’s life as… but as well as shaping what sports is today or what celebrity is today.

Jane Leavy: Christy Walsh was a failed sports’ writer, a failed sports’ cartoonists, failed car account manager at an advertising place. When in February 1921, he decided that the only way he was going to get himself out of his latest jam being fired by an advertising company in New York was to hook up with Babe Ruth. Now, of course everybody wanted to hook up with babe Ruth. He had been sold to the Yankees, December 26th, 1919, had played his first season in New York to great, a claim and an unprecedented show of power and now everybody wants a part of him.

Christie, who’s Christy Walsh? How is he gonna get in front of Babe Ruth to position himself to represent him? Well, finally his nephew, Christie’s nephew told me this in desperation, he found out where Babe was staying in a hotel, climbed up the outside fire escape that you have those that clinging to buildings in New York city opened or hit the window to his room, a crack, saw Babe Ruth in bed with a blonde, climbed through the window, slapped him on the butt and said, “I want to represent you.”

What he wanted to represent him in was selling ghostwritten stories under his name. Now again, there is no radio. How are people going to hear what their heroes have to say about the games and the World Series and their triumphs and their despair? They’re going to read columns that are published and syndicated and published across the country in these little 600, 800 word articles that are purportedly written by their heroes. Well, in fact, their heroes never wrote them. Babe Ruth never wrote his columns. Christy Walsh would find a ghost writer initially himself and then later important New York sports writers to put words in Babe Ruth’s mouth, but he did it successfully and he created a system that was so successful that ultimately he had Ruth and Gehrig and John my brother, Rogers the giant, New York giants and Miller Huggins of manager of the Yankees and on and on he cornered the market and that kind of talent.

People kind of knew that this was not really necessarily what they exactly said, but it still gave the illusion that the athletes were talking directly to them. Walsh was so successful at this. Babe comes to New York, just as the field of marketing and public relations is taking shape, and Madison Avenue is being born under the tutelage of Edward Bernays and Ivy Lee. People are learning how to sell things, commodities, personalities, politicians to people who didn’t necessarily know they wanted them or liked them or needed them. Walsh applied all the techniques that those guys were using to sell soap or whatever else there was to selling Babe Ruth. He got him endorsements that were unprecedented in their value. Other people had endorsed chewing gum or tobacco or whatever, but this was systematic and so much bigger.

That in 1927, for example, Babe Ruth becomes the first athlete to earn more from his accumulated activities off the field than he earned from the Yankees for playing… for hitting 60 home runs and playing the outfield. You’re 73 from the Yankee zone and almost a thousand dollars more for that than that for vaudeville offers, ghost-written columns for endorsements. This was a revolutionary development. What Christy Walsh understood I think before anybody else was that, athletes could be merchandised and marketed as entertainers. He understood that athletes should be paid, not just for the home runs they had hit out of ballparks as in Ruth’s case, but for the people they brought into ballparks. It’s a whole revolutionary and different way of looking at the worth of an athlete. That was a radical departure. It brought us really the original Jerry Maguire, frankly.

Brett McKay: Walsh not only played a part in this crafting this image of Ruth that helped him become a living legend. We also talk about how sports writers, other sports writers contributed to this. This is a fascinating history of America as well because before Ruth, some newspapers had sports sections very few had dedicated sports departments. But now, that’s something we take for granted of course the newspapers going to have a sports section, it’s because it’s going to have a sports department. How did sports writing or how did Babe Ruth or what was the relationship between Babe Ruth and sports writers that… Did they feed off of each other?

Jane Leavy: What one sports writer, and I frankly couldn’t find out who it was. If somebody knows, please let me know. Set of Ruth, he was a Sunday buffet every day of the week. He was the greatest story to write about, that sports writers had ever had. Unlike other sports and basketball certainly wasn’t a big deal then. The NFL was just being formed then. Baseball was daily, and 24/7 coverage was really invented to keep track of Babe Ruth. It was invented by the New York Daily News, which was America’s first tabloid, went to print in June 1919, six months before Harry Frazee owner of the Red Sox stupidly and legendarily sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees.

Suddenly people are recognizing the importance of image over word. Well, think of the images of Babe Ruth in that rubbery mobile face of his and that swing, that upper cut swing, as with his chin lifted, as he looks towards the right field stands, as he’s following the flight of yet another incredible home run. Babe Ruth demanded coverage and when Marshall Hunt, the guy who covered him for the Daily News for so many years, and who was the pioneer of the 24/7 coverage, basically said, “He took up two thirds of every afternoon newspaper in New York.” This is known. The 20s are known as the golden age of sports, but what they really were was a golden age of sports writing and of newspapering. There were I think 15 daily newspapers in New York city in the ’20s, and this is how people got the information. Radio was not yet in those early days available to give you the scores and the updates.

People gathered at street corners to wait for the afternoon paper to come in because of course remember people were playing afternoon games, but the revolution that was going on in mass media, including Tabloid news was as earth shaking and as profound as the advent of personal computing in our lifetime. Imagine suddenly there’s a first Major League game is covered on radio from Pittsburgh in the August 1921. Now it’s still so revolutionary and new that that fall when the Yankees play a pivotal series against the Cleveland Indians that’s going to decide the pennant. People on the East side of New York employee a guy with a pigeon to go to the polo grounds, Yankee stadium didn’t exist yet and have the pigeon fly back and forth from the ballpark to their neighborhood with updates every evening. That’s how paltry information was.

Of course, by 1927, things had changed so radically that the world series was covered coast to coast, not by one, but by two brand new radio networks, NBC and CBS. Babe Ruth came along just at the right moment to be publicized and aggrandized. The one thing they didn’t do was write about his private life. There was an on-the-field and an off-the-field. Nobody wanted to tread on Babe Ruth’s indiscretions. Everybody knew about them, nobody wrote about them. Walsh was very good about keeping stuff out of the press and… Even that precedent was set in 1925 when suddenly he was suspended on August 30th, 1925 for he’d been laid, he’d been out drinking, he’d… What people didn’t know was that his first marriage had fallen apart and Miller Huggins finally is fed up and finds him, suspends him, and it becomes this huge story, front page news everywhere.

The owner and founder of the Daily News, Joseph Patterson, decides enough is enough. We’re done protecting him. We’re going to treat Babe Ruth as news, not as a sports icon. They plastered the picture of his mistress who had become a second wife on the front page of the Daily News and where she would remain for three days. The story was a huge, huge thing all across the country. As I said, it’s a revolutionary moment for both, and they took advantage of it in terms of promoting him and having him be paid for it. They also suffered in the ways that modern athletes do being penalized by how much could now be known about them.

Brett McKay: I like the distinction you make between the two types of journalists. There’s the journalist who went out of the way to protect Ruth’s image. They didn’t say anything about his negative stuff. You call them the Gee whiz journalists and then the journalists who knew that he had some shady stuff going on in his private life, weren’t upset him. They finally disclosed it. Those were the Ah nuts journalist.

Jane Leavy: Yes. I can’t take credit for those terms. They’ve been around in sports writing forever. I think it might’ve been Stanley Woodward of the famous sports editor of the New York Tribune, Herald Tribune who coined them. Yeah, people were writing parables. Grantland Rice was the most famous of them, nationally syndicated columnist who wrote the whole thing about The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. He wrote… They literally would write little poems at the beginning of sports columns and they thought of themselves as writing great dramas. They didn’t go down to locker rooms and ask questions.

They didn’t peer into locker rooms and see… into lockers and see a thing of steroid cream in the top shelf and report on it. They thought of themselves as writing about great dramas of good, and evil, and triumph, and failure, and that predominated. I would say it predominated probably all the way through to 1957 when the New York Yankees and Mickey Mantle at all were involved in a fractious, it was called at the Copacabana. Sports writings always had the rap on it that it was… you’re writing for the… in the playpen. It has evolved and it has grown up and some readers sell it because they want to read the sports page for enjoyment, not for tails of steroids, money and wife feeding and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. It all started to come apart in 1925 with Joe Patterson and Babe Ruth.

Brett McKay: Those Gee Whiz journalists… They helped create the legend there. They were part of creating the legend of Ruth that’s still with us today.

Jane Leavy: Well, for example, the 1927 barnstorming tour, Walsh invited a guy along, a reporter and magazine writer for Collier’s, who went along with them on parts of their train tour of the country. He fed him all this stuff about Babe as the wise elder teaching Lou Gehrig the ropes of how to be a public person and quoted him at length and seriously giving Gehrig lessons and how to behave, which is in retrospect of course, laughable. If there were any indiscretions committed on that tour, neither John B. Kennedy nor Christy Walsh were talking about him, but Gehrig’s quoted as saying, “Oh yeah, it was a real education traveling around with the Babe. We sure would have been arrested a number of times if it hadn’t been for him.”

Well, probably if it hadn’t been for him, they wouldn’t have had committed whatever offense it was that might’ve gotten them arrested. It was to Ruth’s benefit and to Christy Walsh’s benefit to promote Ruth as this is just two years after the horror show of the revelation of the discord in his marriage. Nobody actually wrote what they may have known, which was that they had already signed a separation agreement. It was two years later he’s trying to promote Ruth as this wise elder, this guy who is a mature man of the world, who’s figured out how to behave.

In some ways that’s actually… It was actually true because having hit the bottom in ’25 with this scandal about his marriage and earlier that season, the stomach ache around the world when he passed out, almost died on route back to New York after spring training. Christy Walsh really did whip him into shape in which he made it very clear to him that he had to cut back on the gambling, he had to cut back on the eating, he had to cut back on… If he would have to learn to keep his indiscretions private as Paul Gallico wrote about Ruth later and he learned that lesson well. He wasn’t completely reformed ever charmingly, it never completely reformed, but he was more careful about it.

Brett McKay: Yeah. It was private life. He lived life in excess. He ate a lot. He drank a lot. Womanized, he did… gambled, did everything to the full hilt.

Jane Leavy: It’s funny, people talk about how many hot dogs he ate because of course, so that was the legend was that he ate so many hot dogs. That’s how he got that stomach ache, her ground the world, which of course was preposterous, but at St. Mary’s those boys were fed meat once a week. Guess what the meat was hot dogs. Is it any surprise that Babe Ruth would spend his adult life trying to fill up the holes in the emptiness of his childhood, literally with hotdogs, but then also with the in excess of everything. Having had so little women, beer, gambling and he got himself into real debt. That by 25 when he signed this separation agreement from his first wife, which called for him to pay her a hundred grand, over four installments over four years, he didn’t have the money.

The way Christy Walsh maneuvered to get complete control over him and thus saved his butt financially, and put his house in order, was by saying, yeah, he would lend him the money that he needed to pay his taxes, but Babe Ruth had to give him permission to be in charge of all his money from then on. Ruth signs this letter in 1926, which I found in a collection of Christy Walsh archives. At that point, Christy Walsh is no longer just the syndicator of his ghost-written columns. He becomes his money manager, and his conscience, and his guide. Where Ruth would’ve been without him is hard to describe.

Brett McKay: You mentioned his first marriage ends because of his indiscretions, but what was he like as a family man? Besides the indiscretions, he came from a broken home. Did he intentionally think, I’m going to be a better dad to my kids than my dad was to me? Or did he kind of end up just repeating the patterns he saw that his dad had set down.

Jane Leavy: One of the myths again about Babe Ruth is that as soon as he got out of St. Mary’s, he ran amok. Filling up all those holes in his resume with spending too much money, eating too much, drinking too much. That’s not true. What he did when he got out of St. Mary’s was try to create for himself stability and the family he never had. He married Helen Woodford, a waitress that he had met in Boston at a coffee shop in October of that year. That’s a hell of a year, 1914 for Babe Ruth. He gets out of St. Mary’s where he’s lived basically in captivity since he was seven. He signs with the Orioles. He makes his majorly debut with the Red Sox. He’s sent down to the minor leagues and helps the Providence Grays win a championship, and then he gets married. That’s not the act of a wild man. That’s the act of a guy who’s trying to comport with societal norms.

He’s trying to do the right thing and that… It didn’t work. That a marriage between a 19-year-old and a 16-year-old who knew nothing of the world and he knew nothing of what the world was about to offer him, that it wouldn’t survive is hardly surprising. He was not a particularly great father, particularly to his first daughter, Dorothy, who died never knowing for sure who her birth parents were. He wouldn’t know how to be that kind of parent is again not surprising to me. He tried however, he really did try. I think he was a decent guy trying to do the best that he could.

Brett McKay: It seems with the daughter of his second wife, Claire, who he adopted, they had a better relationship and that was the one you talked to Julia, right?

Jane Leavy: Sure. Yes. Julia, who died at age 102 last winter, was absolutely devoted to him, and saw him and the world through rose-colored glasses, but who blames her? Here’s a guy, her birth father had disappeared from her life. I don’t even know if she knew what I’ve found out which was that Claire had divorced him. Claire grew up in Georgia and really was a Southern kind of girl. She had divorced him because he had beaten her. Along comes Babe Ruth, and he gives her his name and he gives her a life she could never otherwise have had, that her devotion to him is completely understandable.

Brett McKay: Babe Ruth became a living legend while he was alive. I can say, probably the first sports living legend. But then the really sad part, I started feeling really sad, was when he found out he had cancer basically, and he started just withering away. How did Ruth handle that because that’s a big drop? You’re going from like you’re the prime of your life when you hit 60 home runs and just a few years later, you realize you’re on the… you might be dying here soon. How did Ruth handle that?

Jane Leavy: Well, I think he handled it gracefully, extremely gracefully, but the tragedy, if that’s the right word, of his life after baseball began after he quit 1935 midway through a very, very ill-conceived arrangement with the Boston Braves. The Yankees had been done with him at the end of 34, and he wasn’t ready to quit. He wanted to manage. He accepted a contract from Emil Fuchs to return to Boston, allegedly to bring the Boston Braves back to success. In fact, he was just really there to bring in people because they didn’t have a prior succeeding. It was clear by the end of May ’35 that there was nothing left for him to do on the field, couldn’t run, couldn’t catch a ball. In the last game he played, Rhett rolled passed him in the outfield and humiliated him.

From then on, baseball had no use for him, absolutely none. There was no job. He sat by the phone, Claire said, “Waiting for it to ring, and it never did,” and would cry because he had made baseball into the institute and the institution and the crowds and all those boys who would pile out at Rickety ballparks to surround him. He had made them the family he didn’t have as a boy and suddenly it was gone. The repudiation by abandonment, by this second family was a recapitulation of the abandonment of him as a young child, and I think that was excruciating for him.

He had one very brief falling as a coach. For the Dodgers, again, he thought maybe they would hire him as a manager. This is at the end of the thirties, no-go. There was really nothing for him to do. He threw himself into raising money for war bonds in the early ’40s. In 1944, The New Yorker sent a reporter for Talk of the Town to ask him how he felt about Japanese soldiers going to their deaths, charging into line of fire, screaming to hell with Babe Ruth. In Japan, he was still a very big deal and he said, “Well, sounds like those are little itty-bitty ones,” which I think is hilarious. The reporter noticed that his throat sounded very hoarse and I can’t help but wonder whether that wasn’t the beginning of the nasopharyngeal cancer that would take his life.

He died in August 16th, 1948 after returning back from a yet another road trip. What Babe Ruth knew to do was to travel, was to go out. He yet went on another barnstorming tour. Ford motor company was paying him $500 to go, for each city he visited to promote baseball for boys in the Ford leagues. He went to St. Louis where he was photographed on the field before Brown’s game, when posed with Yogi Berra, who later told me he was so nervous he didn’t know what to do. Joe DiMaggio gave him a trophy. Billy Dewitt, the son of the owner, who’s now the owner of the Cardinals went down under the uniform and was supposed to be taught how to hit by the Babe. He was the designated child in the alleged clinic that Babe Ruth was way too weak to give.

By the way, Billy Dewitt’s uniform was later used by Eddie Goodell, the midget who was… I know you’re not supposed to say midget, but back in the day, the midget who was sent up to hit by Bill Veeck famously when he inherited the Browns from Dewitt’s father. He went to Minneapolis where he was interviewed and it was his last interview. It was a radio interview conducted by an 11-year-old child named Johnny Ross. Johnny was blind. Babe Ruth could barely talk. The cancer that had begun to grow in the nasal passages at the back of his nose, which surgeons had been unable to remove had grown and encircled his carotid artery. They had to tie it off. He actually was Guinea pig for a very early kind of chemotherapy that would prove to be in later iterations, very successful, and still used to some extent today in suppressing certain kinds of cancers. By August 1948, the handwriting was on the wall and it was an extraordinary pain. He could eat maybe soft boiled eggs and drink some beer. Johnny Ross, this 11-year-old kid says to him, “Babe, how do you feel on Babe?

“Oh, my head’s hurting, Johnny and my throat, it really hurts to talk.” “Well, who’s going to win the pennant, Babe?” He answers some such, undoubtedly he said the Yankees. “Who’s got the best pitching staff, Babe?” Babe mumbles something. The kid runs out of things to ask and Babe Ruth magnanimously and sadly puts his arm around Johnny and says, “It’s all right. We’re both just about out of words.” Then he went home to die. Then the outpouring of affection, then he was welcomed back, Yankee stadium where he lay in state in The Rotunda in the ballpark that had been named for him, the house that was built.

Brett McKay: He lived a larger… it’s larger than life character. How did he change the game of baseball and why are we still talking about him 70 years after he died?

Jane Leavy: Mike Rizzo, the general manager of the Nationals in Washington said to me, “He was the original original.” He reconfigured the game in his own image. He took it out of the hands of the micromanagers like John McGraw who were accustomed to moving men around the bases, station to station, telling choke up, people like they played little ball. You choke up and hit one to left field and remove this guy from first to second. Then you choke up and hit it to left field and remove it, second to third. Babe Ruth comes along and looks at this, and he was bigger than everybody else. When he gets to Boston in 1914, he’s 6’2 and he weighs 185, 190 maybe, and he looks around and he says, “Well, why should I do that when I can take one swing and put an end to this?” He literally reshaped the game. The power game that is played today is a direct relative of the power swing that Babe Ruth invented and used to hit 714 career home runs.

Having changed the game and ways it was played and the expectations of booms and cracks and torts, flax that would ricochet around Yankee stadium, they then had to make ballparks and equipment that would hold him. Up until then, there were kind of band boxes. Nobody hit balls over fences. One of the, again, a writer for The New York had pointed out that Babe Ruth invention of the modern power games, the home run also created a connection between player and spectator that never existed before because in the moment that the spectator, that the ball heads into the stands and the spectators grab it, they’re connected in a way they had never been before. He recreated it in every way. He took on the institution when he confronted the first Commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the former federal judge over his right to barnstorm in the off season. There was this crazy rule that if you were on a World Series team, you couldn’t barnstorm because somehow that was going to diminish the clout of what was then called Big League Baseball. It didn’t form Major League Baseball till later as a term of art.

Babe Ruth said, “To the hell with that.” Now, he got himself in trouble and he got himself fined and suspended, but the rule was changed. From then on, it was recognized that baseball players had a right to make a living the best way they knew how in the off season. He took on the institution by insisting upon his right to barnstorm against African-American players, which other people did, it is true, but he was Babe Ruth. By playing with and against African-American players, he was giving sanction to them as players who was also providing a nice payday, which God knows they needed, but he was giving credit to, anyway.

He articulated that the colorful play of the Negro leaguers would certainly be a good thing in the major leagues. He took on management by insisting upon his right to have someone represent his interests, Christy Walsh and didn’t end to try to rectify the ridiculous imbalance in power between owners and most of the players who were semi-literate or certainly not equipped to go into negotiations to represent themselves. That imbalance would continue for most players all the way through until when Roger Maris broke the record. He tried to bring his brother with him to negotiate his 1962 contract after hitting 61 home runs in ’61 and the Yankees wouldn’t let him bring his brother because his brother was an accountant. He really struck a blow for players’ rights and he understood that by barnstorming, by taking the game out beyond the Mississippi river, which is of course as far as Major League baseball went in those days, he was doing something good for Major League baseball. He was creating a market that would take another 30 years for Major League baseball to begin to exploit.

Brett McKay: Besides changing baseball, he changed sports in general where we see the legacy of Ruth with endorsement deals. You talked about in the book some of those strides he made in publicity law, which didn’t exist before him and cases that he fought. Those guys who’ve got Nike deals can thank Babe Ruth for that.

Jane Leavy: Knowing how little history most athletes study these days, I don’t think they have any clue how much they owe him.

Brett McKay: Well, Jane Leavy thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Jane Leavy: Thank you. I’ve really enjoyed it.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Jane Leavy. She’s the author of the book, The Big Fella. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find out more information about her work at her website, janeleavy.com. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/ruth, you’ll find links to resources and delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM Podcast. Check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you find our podcast archives. There’s over 500 episodes there as well as thousands of articles written over the years about physical fitness for activity, how to be better husband, better father. While you’re there, make sure to sign up for a weekly or daily newsletter.

If you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the AOM podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium, head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code Manliness to get a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the stitcher app on Android or iOS and you start enjoying ad-free episodes of the AOM Podcast. If you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher, it helps that a lot. If you’d done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think we get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay reminding you all to listen to AOM Podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.