The spoken word is an extraordinary thing. Each language and its intricacies are in a constant state of flux, with words and phrases falling in and out of common usage. As such, we often adopt words and phrases we have heard used without ever considering their original meaning. A perfect example of this is the many colorful phrases in the English language which derive from nautical terms. Chances are you can pick out quite a few phrases from this list that you use at least every once in a while, yet you probably never knew where the term or phrase originated.

Editor’s Note: Critics will point out that there seems to be a penchant in etymological spheres to attribute a nautical origin to just about anything. This idea is so prevalent, in fact, that etymologists even conjured up the tongue-in-cheek (and completely fictional) organization C.A.N.O.E., aka the Committee to Attribute a Nautical Origin to Everything. With this in mind, we’ve tried to avoid some of the phrases with questionable nautical origin.

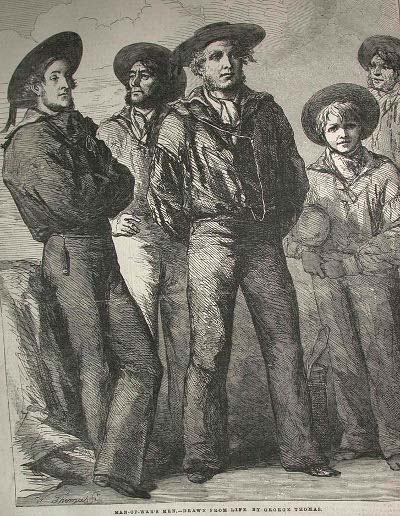

Let’s take a look at some prime examples of nautical terms left over from the age of sail that are still in use today.

“To turn a blind eye to” — to refuse to see or recognize something

Credited to the famous British Admiral Horatio Nelson whose naval exploits during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) are the stuff of seafaring legend. Nelson was injured early in his naval career, leaving him completely blind in one eye. During the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801, the fiery Nelson was serving under a much more reserved and cautious Admiral Sir Hyde Parker. With the tide of battle seeming to turn against them, Parker raised the signal flag, ordering retreat at the discretion of the captains. When Nelson was notified by his flag captain of the signal, he replied, “You know, Foley, I have only one eye — I have a right to be blind sometimes.” Calmly raising his telescope to his blind eye and aiming it in the direction of the signal to withdraw, he continued, “I really do not see the signal.” Thus, having turned a blind eye to the signal of retreat, he continued to fight, and within an hour had secured victory.

“As the crow flies” — in a straight line, the shortest route between two points

It was common for 18th and 19th century ships to carry crows on board for use as a last resort when other attempts at navigation failed. When released, a crow will instinctively head to shore if it is near. Navigators would often time the crow’s flight as a means of measuring the distance from ship to shore.

“Over a barrel” — in a helpless, weak, or awkward position; unable to act

Several theories of origin for this phrase exist, all with convincing supporting evidence. One of the most common theories relates to corporal punishment aboard ship. During the age of sail, sailors found guilty of some infraction of law would often be flogged while bent over the barrel of one of the ship’s guns, leaving them helpless while their punishment was carried out.

“Know the ropes” — to understand or be familiar with the particulars of a subject or business

Ships under sail required a great deal of rope to be properly controlled. These ropes held sails in place, moored the ship at port, and served many other critical roles as well. Knowledge of which ropes did what, as well as a sound knowledge of various knots and their function, was mandatory for every sailor aboard ship. Knowing the ropes was a fundamental part of being a sailor.

“The bitter end” — the very end of something, however unpleasant it is

The cleat or post on which a rope or anchor line was attached at the bow of the ship was often known as the “bitt” or “bitts.” Thus, when the anchor line had been let out in its full extent, with no more available slack, it was said to have reached the bitter end.

“Slush fund” — money set aside by a business or other organization for corrupt activities or money set aside to use for fun or entertainment expenses

During the age of sail, salted meat was preserved throughout the duration of a voyage in barrels below decks. When a barrel of salted meat had been finished off, there was often a slushy, foul mix of fat and salt at the bottom of the barrel which the ship’s cook would save and resell once they arrived in port. This money would then regularly be used to purchase some form of luxury for the crew usually not afforded to them. The practice is recorded in an 1839 edition of Evils & Abuses in Naval & Merchant Service by William McNally:

“The sailors in the navy are allowed salt beef. From this provision, when cooked nearly all the fat boils off; this is carefully skimmed and put into empty beef or pork barrels, and sold, and the money so received is called the slush fund.”

“Three sheets to the wind” — in a state of drunkenness or intoxication

While one might assume that the word “sheet” represents the sail of the ship, it actually refers to the line used to control the sail. When several sheets were loose, a ship’s sail would flail wildly about, often causing the ship to appear to be staggering uncontrollably, as if in a drunken state. The expression was used to refer to drunkenness even during the age of sail and was often part of a sliding scale. When a sailor was just a wee bit tipsy, he was one sheet to the wind. Two sheets to the wind described a sailor who was well-oiled, while three sheets to the wind represented a sailor who was a stumbling, slurring mess.

“Maybe you think we were all a sheet in the wind’s eye. But I’ll tell you I was sober.”

–Long John Silver, Treasure Island

“Jury rigged” — to rig or assemble for temporary emergency use, to improvise

A nautical term dating back to the mid-18th century, jury rigged refers to an improvised, temporary solution to a problem similar to those wonderful contrivances produced by MacGyver when he found himself in a pinch. When a ship lost its mast at sea, either to accident or battle, a new mast had to be improvised from available materials. This mast and accompanying replacement rigging was known by sailors as a jury rig.

“Start over with a clean slate” — an opportunity to start over without prejudice

During a sailor’s turn on watch, he would record the heading to which they steered the ship on a slate kept near the wheel. At the end of the watch, these headings would be recorded in the ship’s log, and the slate would be wiped clean and given to the new watch guard. Thus, the new watch was given a clean slate.

“Son of a gun” — a person or fellow, a rascal

Aboard merchant vessels, it was not uncommon for prostitutes to be kept aboard ship. In the event that one of these women of ill repute became pregnant and carried to term while aboard, the most convenient place to deliver the child was often between two of the ship’s guns, which the lady would lean on for support during the delivery. Upon delivery, the child’s name along with the name of father and mother would be recorded in the ship’s log. If no paternity could be established, the child would be entered as “son of a gun.”

“Scuttlebutt” — rumors about somebody’s activities, often of an intimate and scandalous nature

Kegs or barrels were often referred to aboard ship as “butts.” Often, when a barrel contained drinking water, it would be “scuttled,” or have a hole cut into it so that men could dip their cups in and retrieve water to drink. Much like the water coolers of modern day offices, these kegs became gathering places to secure some juicy gossip or perhaps plot a mutiny.

“First rate” — foremost in quality, rank, or importance

Ships under sail in the British Navy were often ranked and rated by how many cannons they had aboard. A first rate ship would have 100+ guns, while a second rate carried 90 to 99 guns, third rate carried 64 to 89 guns, and so on. Thus, a first rate ship was the best available ship in the fleet.

This is just a sampling of words and phrases that have arisen out of nautical terms. What are some that you may be aware of? Share your contributions!