For nearly 400 years, the Comanche tribe controlled the southern plains of America. Even as Europeans arrived on the scene with guns and metal armor, the Comanches held them off with nothing but horses, arrows, lances, and buffalo hide shields. In the 18th century, the Comanches stopped the Spanish from driving north from Mexico and halted French expansion westward from Louisiana. In the 19th century, they stymied the development of the new country by engaging in a 40-year war with the Texas Rangers and the U.S. military. It wasn’t until the latter part of that century that the Comanches finally laid down their arms.

How did they create a resistance so fierce and long lasting?

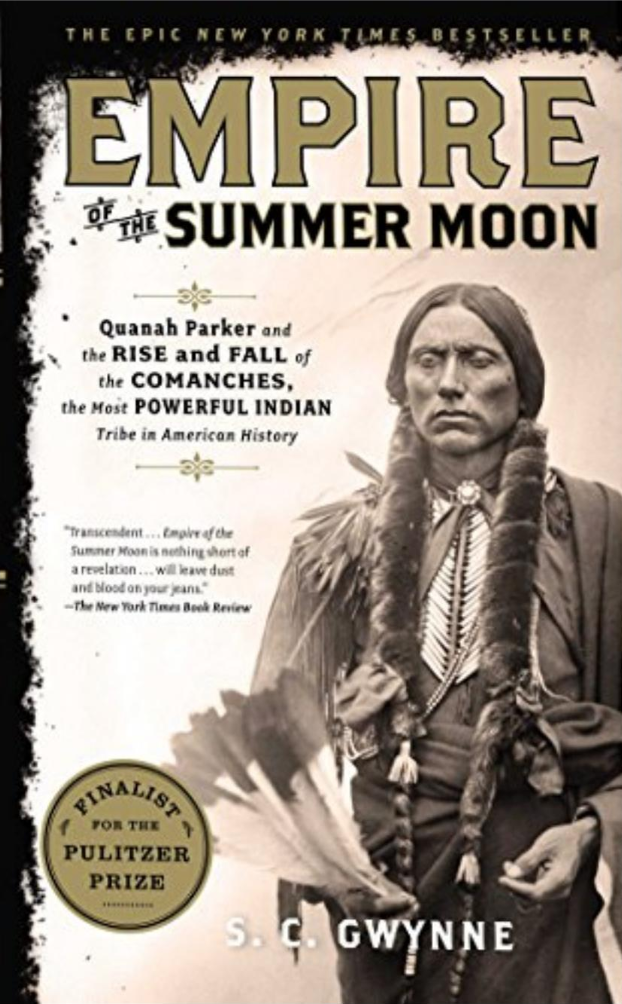

My guest today explores that question in his book Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History. His name is Sam Gwynne, and we begin our discussion by explaining where the Comanches were from originally and how their introduction to the horse radically changed their culture and kickstarted their precipitous rise to power. Sam then explains how the Comanches shifted from a hunting culture to a warrior culture and how their warrior culture was very similar to that of the ancient Spartans. We then discuss the event that began the decline of the Comanches: the kidnapping of a Texan girl named Cynthia Ann Parker. Sam explains how she went on to become the mother of the last great war chief of the Comanches, Quanah, why Quanah ultimately decided to surrender to the military, and the interesting path his life took afterward.

This is a fascinating story about an oft-overlooked part of American history.

Show Highlights

- Why does the history of the Comanches get looked over in history classes?

- The origins of the Comanche people

- What the introduction of the horse did for the Comanches

- The transition from hunter culture to warrior culture

- The unique style of Comanche warfare, and their culture of brutal torture

- How were Comanches organized? Why couldn’t white people figure it out?

- The Fort Parker raid and the capture of Cynthia Ann Parker

- The incredible discovery of Cynthia, and why she refused to re-assimilate

- How the Texas Rangers became so successful

- What led Quanah Parker to ultimately surrender?

- How did Parker end up as an American celebrity?

- What Sam ultimately took away from the writing and researching of this book

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Red River War

- AoM series on the Spartans

- Books So Good I’ve Read Them 2X (or More!)

- Lonesome Dove series by Larry McMurtry

- 21 Western Novels Every Man Should Read

- The “noble savage”

- Fort Parker massacre

- Cynthia Ann Parker

- Quanah Parker

- John Coffee Hays

- Samuel Colt

- Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee

- The Searchers

Connect With Sam

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Recorded on ClearCast.io

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

MSX by Michael Strahan. Athletic-inspired, functional pieces designed for guys who are always on the go — available exclusively at JCPenney! Visit JCP.com for more information. Also check out his lifestyle content at MichaelStrahan.com.

Omigo. A revolutionary toilet seat that will let you finally say goodbye to toilet paper again. Get 20% off when you go to myomigo.com/manliness.

Saxx Underwear. Everything you didn’t know you needed in a pair of swim shorts. Visit saxxunderwear.com and get $5 off plus FREE shipping on your first purchase when you use the code “AOM” at checkout.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: For nearly 400 years, the Comanche tribe controlled the Southern Plains of America. Even as Europeans arrived on the scene with guns and metal armor, the Comanches held them off with nothing but horses, arrows, lances and buffalo-hide shields.

In the 18th century, the Comanches stopped the Spanish from driving north from Mexico, and halted French expansion westward from Louisiana. In the 19th century, they stymied the development of the new country by engaging in a 40-year war with the Texas Rangers and the U.S. military. It wasn’t until the latter part of that century that the Comanches finally laid down their arms.

How did they create a resistance so fierce and long lasting? Well, my guest today explores that question in his book, Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History.

His name is Sam Gwynne, and we begin our discussion by explaining where the Comanches were from originally, and how their introduction to the horse radically changed their culture and kick-started their precipitous rise to power.

Sam then explains how the Comanches shifted from a hunting culture to a warrior culture, and how their warrior culture was very similar to that of the ancient Spartans. We then discuss the event that began the decline of the Comanches, the kidnapping of a Texan girl named Cynthia Ann Parker.

Sam explains how she went on to become the mother of the last great war chief of the Comanches, Quanah, why Quanah ultimately decided to surrender to the military, and the interesting path his life took afterward.

It’s a fascinating story about an often-overlooked part of American history. After the show’s over, check out our Show Notes at aom.is/comanches.

Sam joins me now via Skype. Sam Gwynne, welcome to the show.

Sam Gwynne: It’s good to be talking to you.

Brett McKay: You’re the author of the book, Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History.

I grew up in Oklahoma. I live in Oklahoma. You have to know Oklahoma history, but they always talk about just the five civilized tribes, which is an interesting history. The Comanches get a passing, and the story is just phenomenal.

Sam Gwynne: It’s true in Texas, too. They just blow by this. They certainly did, my daughter was in high school 10 years ago here, they just blew right by it. They never stopped.

Brett McKay: Well, why is that? Why does the history of the Comanches get overlooked or blown by in history classes?

Sam Gwynne: I don’t know. It’s a really good question. The plains, or the high plains, Comanche plains are the last part of America to be settled, of course. The east settles, and the west settles, and then you’ve got this thing sitting out here that is really the plains extending down from the Northern Plains, that were controlled by the Sioux, through the Central Cheyennes and Arapahoes, and then Comanches.

You had this very uncivilized, shall we say, middle that took a very long time to settle. On some level, I think that it may be because they’re just … Because of that fact, there just wasn’t anything out here really. This was a frontier.

And because it was a frontier, it wasn’t crawling with reporters, necessarily. It just never had the play. Even something like the Red River War, which was an extremely significant moment in American history, was the end of the frontier.

And the frontier ended here in Texas. It didn’t end in California. It ended here. These things didn’t get covered very well. They didn’t get written about that well. I don’t know. It’s been a privilege and an honor for me to be able to restore it in some way, certainly here in Texas, because the Comanche period here in Texas was not really part of the conversation.

Brett McKay: What led you down that path? Did you come across a story? Or was it your daughter going through Texas history in high school, and Comanches got a quick pass? Did you come across some of these? There’s a bigger story here that I need to write about and research.

Sam Gwynne: Yeah. It is all related to me, the Connecticut Yankee, moving to Texas and having absolutely no clue about the history here, and walking around saying, “Oh, wow. Look at that. Gee, I never knew that.” Really? This is the idiot easterner who doesn’t know any better. That’s who I was. And I thought, “This is just incredibly cool.”

I went out on the High Plains, and then I heard about these nomadic tribes that lived out there, and this whole world that I had never known about, I’d never even heard about.

So living here, what made me write it was moving to Texas, which I did 26 years ago, and I’m still here. I came here. I was just kind of on the circuit. I was a bureau chief for Time Magazine. I’d been in L.A., Los Angeles, for Time Magazine, and Detroit and Washington and New York. This was another stop on the way. It was like, “Okay.”

But I got here, and I just started hearing. First of all, you start hearing things, because Texas is really close to its frontier. And I mean, when I grew up in the East Coast, whatever Native Americans had been around when the white man arrived had been pretty much killed off, at least in large numbers by disease mostly, but also by weapons and bullets and things like that.

The subjugation of the Indians had happened hundreds of years before my forebears ever got off the boat. In Texas, that wasn’t true. The history was right here. It was just in your face. You’re from Oklahoma. You know this.

Brett McKay: Right.

Sam Gwynne: This is immediate. The last of the Indians did not surrender here until 1875, and there was a lot of jostling on and off the res that went on into the 20th century. And I would just hear these stories. These were stories that seemed like they were almost current day. It was a very different take on it.

But yeah, it was all where I was, and this incredible sense of the land, in particular, a love affair that I’ve had with the land in west Texas, and just this incredible history that happened down here.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Let’s talk about the Comanches because, like I said, I didn’t know much about this tribe. I think when we talk about Native Americans, particularly here in Oklahoma like I said, you talk about the Cherokees, the Choctaws, the Chickasaws. Or if you’re in the East Coast, you talk about the Iroquois.

The Comanches don’t get much, they don’t get talked about. But they’re a fascinating, fascinating culture. They were primarily in Texas, west Texas, southwest Oklahoma, and went into New Mexico. But they weren’t originally from there, which I didn’t know. Where were they from originally?

Sam Gwynne: The origin of the tribe is … You sort of put this together as best you can, or rather the people who were there at the time put this together as best as you can.

As far as we know, they were originally a Shoshone language group tribe. And they were in the Wind River Mountains; they were basically the foothills of the Wind River Mountains in Wyoming. And this would be now going back prior to the 18th century.

From what we know, they were back then, this was before the Spanish horses arrived, and were distributed throughout the plains. They didn’t have horses, they were a foot-bound band of nomadic hunter-gatherers.

And they were, as far as we know, a tribe that was not militarily powerful. One of the reasons that is surmised is because their hunting grounds were not the rich hunting grounds of the buffalo or bison plains. But they were less good hunting grounds.

So you had this amazing thing that happened in history. And it happened away from the eyes of white men. Again, you ask, “Why do people know these things?” Well, this thing you can see in flashes, or rather, the Spanish and the French could see it in flashes.

But suddenly, what happens is the Spanish arrive in the New World right after 1492, after Columbus and the Spanish arrive in the New World. And they bring horses with them.

And with them comes this incredible technology of horses that’s thousands of years old, that’s very specific and the Spanish are really good at it, and they bring these little horses, mustangs, that are really well adapted to the arid areas in the west. And they were very concerned initially about letting the technology out. They didn’t want to let it out because they knew what might happen.

Well, it got out. Without going into all of the details, basically the Native Americans on the plains, on the American Plains, North American Plains, got hold of the horse. And the tribe that was by far the best at this were the Comanches.

For some reason, nobody really still understands what there was about them that understood the horse in terms of breaking, breeding, whatever it was, stealing, selling, racing, hunting with, fighting, whatever, they were better than anybody else at it.

And endowed with this new power, this phenomenal technology of the horse and mastery of it, starting in the 17th century, aided by such things as The Great Horse Dispersal, which is when the Spanish were driven out of New Mexico briefly, and 20,000 horses got out. They were the Comanche with horses now. Now they start to move south from those Wind River Mountains, which is where I said they were, in Wyoming.

They’re going to move south. They’re going to challenge everybody and anything in front of them. And what they’re going to challenge for is the greatest food source on the plain, which is the buffalo, who are essentially in the Southern Plains. I mean, there were buffalo in the Northern Plains, but nowhere near the numbers.

So the new power, the new great Plains power is going to do what you think they would do. Then they move south and they migrate. That is when essentially, they enter this, they enter history as they start to migrate south.

Brett McKay: They became even more adept hunters because they were able to migrate more quickly with the buffalo. It gave them an advantage in hunting buffalo as well, because they could chase them down from their horses.

But as you note in the book, something else happened as they started colliding with other tribes in the area, particularly the Apache. Their culture started changing from a hunter culture to a warrior culture. How did that manifest itself? What do we know about that?

Sam Gwynne: Yes. That’s a really good point. The Comanche, the incredibly warlike, you’d have to look to something like Sparta, a culture that was built on war, where social status came from war, where everything was oriented that way. It came from a fairly long war against the Apaches that amounted in the end almost to a genocide.

The Comanches were sweeping south from Wyoming, well, what is now Wyoming, into the Southern Plains, which as you said, was think of eastern Colorado, eastern New Mexico, western Kansas, western Oklahoma, western Texas, the Southern Plains.

This is where the Comanches are moving toward. There’s ground occupied by Apaches, who have this long war. It’s very bitter and mostly unrecorded and very, very brutal. But the Apaches lose.

Eventually, by the time you see Geronimo running around the border lands of Mexico, that’s where the Apaches eventually ended up, down along a strip along the border lands. But what’s interesting about this, getting back to your original question, is the Spanish, before I get to it, the Spanish, by the way, see this in flashes.

The Apaches, or the Spanish have this kind of capital up in Santa Fe, what is now New Mexico. They see this strange thing happening. Their enemies, their great, implacable enemies, the Apaches are going away. Something’s going on. They don’t quite know what it is. Something’s happening to their enemies. At some point, they realize what’s happened to their enemies. They’re losing a war to the Comanches.

The Apaches are being driven south. But what’s happening to the Comanches is because of this long war, it reorders their cultures. It is now a culture of war. It is now a culture particularly because they’re so good at it. They work at it. They get better at it.

They can subjugate other tribes, which they do. They can drive tribes off their hunting grounds, which they do. They can nearly commit genocide on the Apaches, which they do. So you have this amazing cultural shift inside the Comanche Nation.

By the time the first Anglo-Europeans heading west see them in Texas in 1830, what, 2 or 1834, it’s this unbelievably unified militaristic tribe that controls a 250,000 square mile empire, with 20,000 vassal tribes in it. It’s not an empire like Rome. But it’s a plains empire, and it’s built on their martial abilities. So it completely changed them, and it turned them from … I guess if you look at them originally, kind of a bunch of nomadic Stone Age hunter-gatherers, into this magnificent mounted war machine.

Brett McKay: You mentioned Sparta; Sparta’s known for its agoge, how they raised their boys to become warriors. The Comanches had something similar. They had sort of a training that starts very young, like as young as three for their boys to become these great cavalrymen, these great warriors of the Plains.

Sam Gwynne: They were indeed, that is true. They were very, as the culture evolved, the boys had to do really two things. And really, only two things. The women had to do everything else. And the two things were hunt and fight.

Yes, as the culture changed, and as their abilities with the bow and arrow, the abilities with the horse, became more sophisticated, these rituals of passage as you were a kid, when you were first turned out to hunt small game, and then later on, larger game; and particularly taught to ride.

The Comanche power came from certainly their ability to fight with your hands and with the plains lances and with bows and things like that. But it also primarily came from the horse. What was trained as much as anything, or more than anything, was horsemanship.

They were just phenomenal horsemen, and to the point where the tales told about them are scarcely believable, even today, what they could do on a horse. It was part of that big cultural change.

Brett McKay: There are things like they would shoot a bow and arrow from beneath the neck of a horse, while it’s still galloping.

Sam Gwynne: White men couldn’t believe that one.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Sam Gwynne: The other thing they could do is they could discharge arrows at a rate that just defies imagination. It is literally, I’m snapping my fingers now, like that. And if you don’t believe me, go to this website where this guy Lars Andersen will show you. There’s no quiver involved. It’s a way of holding the arrows. Anyway, all the things that they could do from particularly shooting.

But also just riding; that trick that you’re talking about, where you loop down a leather loop over the saddle, over the very middle of the Spanish saddle. It would hang over the neck of the horse, which would of course conceal them from their enemies, and also enable them to discharge arrows. But with such force that it would go through the head of a buffalo. Very deadly, and as I say, when the white men first saw them, they couldn’t quite believe what they were seeing.

And the skills with horses applied to everything. Breaking horses. They watched them break these horses, and the white man had never seen anything like it before.

The Comanches would trail a horse, or a couple of horses and they would just trail the horse. You couldn’t catch the horse, of course, because the horse was wild. But every time the horse got near water, they would kind of bother the horse. It’s the same way a wolf brings down a moose.

This would go on for a couple of days. And eventually, the horse was just completely foaming at the mouth and dying of thirst; there were various techniques and ways this happened.

But at one point, the Comanche warrior would go and literally cup his hands over the muzzle of the horse and blow into its nostrils. Suddenly, the horse goes from this wild thing to being immediately gentled.

Anyway, there were all these stories that people had told about the Comanches that no one, no white man had ever seen before, anyway. You’ve got to be careful saying “no one.”

Brett McKay: Right.

Sam Gwynne: The whites had never seen them before.

Brett McKay: Speaking of something that flummoxed Europeans when they first encountered the Comanches, and going off this idea of the warrior culture of the Comanches, they had a specific type of warfare, style of warfare. When the Europeans first encountered it to the Spanish, they couldn’t stop it. They had never seen it before, and it threw them for a loop.

Sam Gwynne: For one thing, the white man always insisted on this Napoleonic confrontation, where you would march out and there you were in your ranks. You would take your regiment and it would be standing in its ranks, two or three deep in the regiment. Then they’d line up and, “Ready, aim, fire.”

The Comanches would never take that fight. They would never get near anything like that. They would never fight you like that. They would not obey all of the rules of white men’s war, which in those days, was essentially lining up two regiments against each other and firing at each other, from at a distance of about 100 yards away.

They wouldn’t play that way. They were all about stealth. They moved making cold camp, so there was no fire. They swam their horses through frozen rivers that you wouldn’t think you could cross. They attacked by night; they gave no quarter, which is another thing that the white men weren’t really used to.

But especially I think that this idea of completely mobile warfare, Comanches were mobile. A dragoon is a thing what would characterize a lot of the troops in Spain. A dragoon is a type of soldier who are usually pretty heavily mounted, heavily armed and heavily mounted. He rides the horse to the place of the fight, gets off the horse, and fights. It’s like driving a car to the battle. Except it’s a horse.

Comanches were entirely mounted, and fought mounted, and did everything mounted. It was the thing that distinguished them, really, from everybody else. It was the complete oneness with the horse. And it was, I think as much as anything, again, I keep coming back to the horse. But as much as anything, it was the unity of warrior and horse that made the difference.

Brett McKay: Going back to that idea you said about the Comanches were very similar to the Spartans. As I was reading this book, your book, I was like, “That’s exactly right.”

Brett McKay: Training to be a warrior, since a little boy, same thing with the Spartans, the Spartans also loved to gamble. The Comanches’ men also loved to gamble, loved to gamble. The Spartan men didn’t do anything except for train for war, hunt. They didn’t do anything else. And that same thing with Comanche.

Sam Gwynne: Same deal.

Brett McKay: Yeah. As I was reading that, I thought it was really interesting.

Sam Gwynne: It’s all very similar. And, in both places, your social status was entirely based on war. And that’s where how many horses you had, how many wives, whatever, was with those things came from performance in war.

Brett McKay: Yeah, for the Spartans, it would have been like the trophies you brought home: shields, armor, that you brought home from your conquered. Well, another part of Comanche warfare is that …

Okay, I’ll tell you how I found your book. I’m a big Lonesome Dove fan. I’ve read the original novel four times, named my kid Gus after Gus McCrae. This year I finally decided, “I’m going to read the other novels in the series.” Because McMurtry wrote Dead Man’s Walk-

Sam Gwynne: Comanche Moon.

Brett McKay: … a bunch of prequels. I was reading Comanche Moon, and Dead Man’s Walk. And they’re describing the torture that the Comanches did. I was like, “Ahh, McMurtry, he’s got to be doing artistic license. It didn’t happen like this.”

Then I started researching, I found your book, then I learned, yeah, the Comanches were experts at torture. What was going on there?

Sam Gwynne: Yeah, one of the things you have to come to terms with, if you’re a historian writing about Native Americans … and this isn’t just confined to the plains … is the practice of mistreating or torturing captives. And it is all over America, North America.

I don’t know much about the tribes south of the Rio Grande side, but I do know about the ones north. It was part of the culture. Certainly, in the Plains Indians, it was. And it was pretty simple.

Let’s just go back for a moment to the time before the white man came. You would have Indian tribes that pretty much fought each other all the time. There was a culture of raiding, and the raid always produced a counter-raid, then a counter-counter-raid, and then there were vengeance raids. This kind of went on.

The code was pretty similar, and the Comanches certainly had it. We’ll just look at the Plains Indians for the moment. The rest of the Plains Indians did too. But what that said was, if you captured a baby, you just killed the baby. Baby’s useless and an annoyance, and you can’t take it on the road, so to speak.

Young children might be killed, or they might be spared. The Comanches in particular had trouble keeping their numbers up, so they took captives, and they were very welcoming. All kinds of captives; captives from Utes and Apaches and Navajos and people from Mexico and German Americans. They would take whoever they could get.

Usually, the children captives they allowed to live would be in the eight or nine, 10, 11, maybe, that range of … There’s a lot of famous ones, and I write about them. Then you have, let’s say, a teenage girl or a 17-year-old girl would be made a slave, probably a sex slave as well as a slave of labor. Hard labor forever.

Then you had the warriors in the tribe. They would be killed. If they were captured alive, they would be tortured, either slowly or quickly. That all depended on how much time the winning tribe had, or the tribe that had them had.

So you had this idea of just absolutely crazy mistreatment, by the standards of that enlightened culture of the Renaissance, and the Judeo-Christian tradition and all this culture that has these ideas of absolute good and evil, which the Indians don’t have.

Suddenly, this culture … in Texas, anyway … from this Anglo-European culture arrives on the frontier, and looks at babies being killed and pregnant women being eviscerated, and people being tortured to death by their eyelids cut off and the penis tortures and the ant tortures and the sun tortures and all the tortures that McMurtry writes about, and that I write about.

And they’re just absolutely horrified. I mean, these white people are horrified as you are, as I am. But it took the white people to be horrified; see if I can explain that.

There was, if you will, a golden rule. Like it was a backwards kind of golden rule, but it was still a golden rule. It was, you tried to treat your enemies the way that you might expect to be treated. All of the Native Americans out there, if you took Navajos and Comanches, for example, the warriors had exactly the same expectations of what was going to happen.

The women with children had exactly the same expectations. In other words, if their child, if their baby was taken, the baby would be killed. If their tribe took a baby from another tribe, they would kill the baby. There was a stasis; there was a stasis of expectation, I guess. It was an interesting moment in history, because you have a culture of raid and counter-raid, and we’re talking about just Indians, now, before the white man gets there.

And all this stuff that just curdles the white man’s stomach going on, except that it didn’t bother the Indians. Not only that, but you had the culture of raid and counter-raid and torture. But also you had this pretty much infinitely renewable and sustainable food source, the buffalo. So there was, if you look at, say, late, let’s say 18th century, early 19th century on the plains, this is a totally sustainable society.

They understand the ground rules that each other lives by. They got plenty of food, and everything’s fine. Now you wouldn’t think it was so fine if you got caught, and had your eyelids … I mean, whatever, I won’t go on. But that’s what it was.

White men arrived. Oh, the horror, the shock. And lo and behold, the white people learned from them too, and when the Texas Rangers were said to give no quarter … Well, that was true, they didn’t give quarter. And not giving quarter, when you think about it, if someone’s attacking a village with men, women, and children in it, it’s not a very pretty thing. So it happened to both sides.

But it is an interesting thing, as a historian, I think, as anyone who reads about it, too, you have to come to terms with this. This is what they did. It’s a fact. And they did it all over North America.

Not only that, but the white people learned pretty quickly about scalping and torture themselves, and often employed it just as liberally as the Native Americans did. It’s a very touchy and difficult thing to come to terms with.

Brett McKay: It is. I think you know this in the book In America, at least, we have that very Rousseau idea of the noble savage, the peaceful et cetera. But as you said, it is what it is. That’s how it happened.

We’ll talk about how warfare, how Anglos changed the manner of war here in a bit with the Texas Rangers. But to note, because of the style of warfare the Comanches had, they were able … and also another thing is interesting that the Comanches, unlike a lot of other tribes, say like back east, or the Cherokees or the Choctaws, their political organizations. There really wasn’t a single chief for the entire Comanche tribe. It was more fluid and more flat.

Sam Gwynne: It was, and the white men never understood that. The Comanches were organized … a lot of plains tribes were … but the Comanches were organized in bands. If you looked at it as a management chart, it’s a completely horizontal management chart. And you would have within the bands, you would have a civil chief and a war chief. Technically.

But even then, so not only was there not one big head guy … and the white men always thought they were making the treaty with the big head guy … There never was any big head guy.

Brett McKay: Right.

Sam Gwynne: They just totally got that wrong. But not only was there not a big head guy, but even within the bands … Comanches had five major bands, early 19th century. But even within the bands, it wasn’t really hierarchical. It wasn’t like, “Well, the president and others, the vice president, the assistant vice president.” Not like that.

Let’s just say that you were the young Quanah Parker, and you were 18 years old and you wanted to get a raiding party to go raid the … oh, the Utes or the Navajos or somebody who you were going to raid.

Your ability to become a “war chief” depended on your ability to recruit. If you could recruit 50 people to go on a raid, well, you were the war chief. That was your party. You couldn’t over overridden by somebody who said, “You can’t do that.” You could recruit it, you could do it.

Again, if you look at like from an American management point of view, it’s a completely flat organizational structure. Which gave it advantages in some ways, and it gave it also some great disadvantages. Because of a lack of the militaristic central control that you would have seen in an army of say, the Civil War or something.

Brett McKay: So, yeah. All these things about their style of warfare, their fluid political organizations, so it made it hard for Anglos to figure out who’s in charge and make treaties or whatever. That allowed the Comanches to fend off the Spanish Empire, which again, conquered the Incans, the Aztecs, those great empires of South America and Mexico.

The Comanches were able to hold these guys off for over 100 years, and white people off in general. Until the Americans started arriving in Texas around early 1800s, right?

Sam Gwynne: Right. And the term that historians used for what the Comanches were … and again, we’re looking at this 250,000 square-mile empire that again, eastern New Mexico, eastern Colorado, western Texas, western Kansas, western Oklahoma … that chunk of land there.

It was so powerful that it essentially stopped … or not essentially … it did stop the expansion of Spanish power into the New World. The Spanish thought that the place was theirs. They ran into first Apaches, and then Comanches. But more particularly, Comanches.

You had Comanches stopping this northward power surge of the Spanish into North America. You had Comanches stopping this westward surge of French power coming out of the Louisiana Territory. You had them stopping cold the Manifest Destiny, the movement westward driven by the idea of Manifest Destiny, of the Americans, of the United States of America.

You had this phenomenal influencer of history, I guess, because nobody could do anything with this. It was one of the reasons this was the last part of North America to be settled, is you had an impenetrable block. Roughly speaking, if you look at the war that the Texans, and then later the United States of America fought against the Comanches, this was about a 40-year war. Essentially, along a single line.

The line would roll west toward Wichita Falls sometimes, backward toward Dallas sometimes. But the United States never fought a war against any tribe that did anything like that. It essentially just stopped everything for a very long time.

And the reason that in the title and the subtitle of my book, Empire of the Summer Moon, I say these guys were the most powerful tribe in American history. It’s for that reason.

They held up everything. They stopped everything, and they stopped it for a long time. Eventually, of course, they lost. But the west wasn’t “won” for the white man and his civilization until, really, until the Plains Indians lost it.

Brett McKay: This brings us up nicely to where Quanah Parker’s story starts. Because it stars with a raid on some Texas settlers, I think it was like the 1820s, thereabouts. The Parker Raid. Tell us about the Parker Raid and the ramifications of it.

Sam Gwynne: Okay, this is the great thing about this story is, on the one hand, you have the story of the Comanche tribe, which is a great dramatic story.

Brett McKay: Right.

Sam Gwynne: Great arc of the rise and fall of the Comanches. They’re this little tribe that a no-account tribe. But they get the horse, they become dominant, they sweep south, they change history. That’s all big-picture stuff. It’s great, it’s cool.

But buried in the middle of that story is the little personal family story about the family. About the Parker family. What happens is the Parker family has gone ahead and they’ve been given these great headrights from the Mexican government.

One of the reasons the Mexicans are giving out all these headrights to people from the United States is because they want to settle these lands, these border lands in Texas. And by settling them somehow, kind of solve their Comanche problem.

So there’s this raid on the Parker fort … this is 1836, raid on the Parker fort. And they take a bunch of hostages. Among them, Cynthia Ann Parker and they ride off into the plains. With little old nine-year-old Cynthia Ann Parker, blonde-haired, cornflower-blue eyes, the whole deal. But they leave.

It was the most typical raid you could possibly imagine. The Indians did this to each other all the time. This just happened to be … These were white people, predestinarian Baptists out of Illinois by way of Virginia. So this starts this incredible tale.

Little Cynthia Ann Parker, she’s kidnapped, she’s taken away. She becomes part of the tribe, she becomes completely assimilated into the tribe. She marries a war chief.

She is, over the years, Indian ancients and various people knew where she was, but she wouldn’t come in, which shocked everybody of course that the white squaw, as they called her, would want to spend her life with these horrible savages, when she could have her wonderful European culture that she came from.

This is the first part of the story. Cynthia Ann goes out and she won’t come back. She has children, she marries the war chief. And she has one of her sons is named Quanah.

Then, by complete accident one day, a bunch of Rangers, Texas Rangers and militia, happen to attack a camp where she is located, and they re-capture her.

This is one of the more amazing moments in the history of the frontier, because you had this the squaw that would never return, and they refused to return her to her culture. Well, now they’ve got her. They put her up on a box in Fort Worth, and everybody gawks at her and poke at her, pokes at her and gawks at her up on this box.

When she was captured, she’s captured with her daughter, named Prairie Flower. But her sons get away. One of whom was Quanah. Cynthia Ann gets dragged back, increasingly farther and farther and farther away from the plains, increasingly into this Anglo-Saxon culture of her family, the Parker family, and she’s ever more miserable.

Meanwhile, her son who wasn’t captured, Quanah, is out loose on the plains, rising to become the next, the last great chief of the Comanches. The man who finally surrenders what remains of his tribe after all the buffalo are killed in 1875.

In a way, you have this 40-year war that I talked about between the Comanches and the first the Texans, and then the people from the United States. Essentially, that begins with the kidnapping, essentially, of Cynthia Ann Parker. It ends with the surrender of her son, the last and greatest chief of the Comanches, Quanah, in 1875. They’re amazing bookends.

Quanah then goes, elects to walk the white man’s way, goes onto the reservation, becomes the wealthiest and most influential Native American of the reservation period, and on and on. When he finally, among other things, he attempts to, and does locate, the grave of his mother. Anyway, the story goes on. But it’s one of the great tales of the frontier.

So when you write about it, like when I write about it in my book, I get to tell then the big-picture tale of the Comanche tribe. But I also get to tell this, when you’re reading that, you’re never very far from the smaller story about this little girl and her son.

Brett McKay: No, yeah. When you mention that part where they found Cynthia Ann again. I get they gave her back to her uncle, and her uncle just put her up on that box and yeah, you said everyone was just gawking, and she started crying.

Sam Gwynne: To be honest, she was a curiosity. It’s hard to imagine that the animosity … today, anyway … the animosity that people on the frontier felt for say, Comanches. Everybody knew somebody who’d been killed or tortured. It was very bitter and it was very brutal. So to have one of them, a live one right there … but she’s white … it just astounded people.

Brett McKay: Yeah. You mentioned the Texas Rangers found her. This is another part of this Comanche story, and the story of the Parkers and Quanah. This is also the story of how the Texas Rangers, of the mythic Texas Rangers, came to power, came to rise.

You mentioned this earlier, one reason why the Texas Rangers were so successful at battling Comanches is that they learned to fight basically like Comanches.

Sam Gwynne: They imitated everything they did. That’s where the Rangers came from. And one of the things I loved about Lonesome Dove, which you and I both like, because Gus and Captain Call were rangers of that era. That’s who they were. That’s why they were good. They fought Comanches and Mexicans as everybody did in San Antonio.

But yeah, I’ll tell you a story. This is my favorite story that came out of my book, and I didn’t know it before I wrote it. So let’s go to the 1830s, and we’re in San Antonio now. This is right on the edge of the Comanche frontier.

Well actually, let’s take 1836 and forward. San Antonio’s now part of Texas. What Texas would do, they were very generous with what they called headrights. They would give you headrights, would be rights to land; basically, the land was free. All you had to do was go out and survey that land. Then it was yours.

People flocked to San Antonio, and they would secure their headrights, which would be … I don’t know, call it a few hundred, 600, 800,000 acres. However many acres outside of town. Then the surveyors would go out and survey it. And the surveyors would be killed in all sorts of … Talk about torture.

The Indians knew exactly what the surveyors were doing. It wasn’t like, “Oh, the machine that steals the land.” No. The machine actually stole the land, and they knew that. The machine stole the land. The surveying equipment did. So they killed them in all sorts of imaginative ways.

Then the people in San Antonio would send out armed guards with the surveyors. Now the death toll rose. In fact, if you see the number, the percentage of dead in 1837 … I think this is in my book somewhere. 10 or 15% of the population in San Antonio died every year, trying to do this. Comanches didn’t like this.

One of these surveyors was named Jack Hays. He was this skinny little 23-year-old guy who had this ability to keep surveyors alive long enough to get the headrights and secure the land.

So this group kind of coalesced around him of young guns. They were all 22 years old, and they were all crazy. And they were all very tough, and the Texans had names for them. They called them mounted gunmen, and spies. It wouldn’t be called spies, I don’t know why.

Eventually they came up with a name for them that stuck. It was Rangers. What the Rangers did was they imitated everything the Comanches did. They made cold camps; again, you don’t build a fire because they can find you.

They learned from their various scouts that they used to find the Comanches, how to track bird flight, how to cross frozen rivers, particularly horse management, which really the white men didn’t really understand at all. They didn’t understand how you fought on horseback, just how you lived with a horse in an essentially combat situation.

So this goes on, and Hays makes a name for himself. He’s the man. He’s got one problem, now. When his mounted men, who are really good on horseback now, confront Comanches, they’ve got only three shots. They’ve got a Kentucky long rifle. Bang, that’s one. And they’ve got two single-shot pistols. Two, three. And that’s it. You can’t reload those on horseback. You can’t do it.

They were going up against Comanches that had the clusters of arrows in their hands; they could shoot very rapidly. They were at a great disadvantage in firepower. They couldn’t do anything about it. They won their battles largely by just being unbelievably aggressive. They would ride forward and full speed screaming, and they would discharge their weapons. And they would often just win by panache, by just guts. And with very much the Captain Call character in McMurtry.

Okay, now something really interesting happens. So go to the East Coast. The East Coast, there’s this guy named Samuel Colt. This little inventor guy. He’s invented this weird little weapon. It’s a five-shot pistol. I think it’s a 36-caliber five-shot pistol.

But what it’s got, it’s got a, well, five shots. But it’s also got a cylinder that is removable. So that you can shoot the five shots, remove the cylinder, and put another cylinder in. He thinks it’s a great cavalry sidearm and everything.

Well, at that moment, the United States did not have a cavalry, and nobody wanted this weapon. It was a clever weapon that had no use, as far as anybody could see. Colt goes bankrupt, loses the blueprints. So. However.

Somehow, the Texas Navy bought a crate of those things, of the five-shooters, the Paterson Colt five-shooters. And somehow it sat in a warehouse in Galveston and somehow, Jack Hays and his Rangers in San Antonio, which is about … I don’t know, maybe 200 miles from there … got ahold of it. Got ahold of the crate of guns. He immediately understood what it did. Hays immediately understood that it would equalize the thing.

So now the Hays Rangers, now they’re training and training with these five-shooters, and they’re getting really good at them. And in 1844, they take them out and try them out in Sisterdale, Texas, at the Battle of Walker’s Creek. And they win. And everything that Hays thought would happen, happened.

So you had this incredible moment in history. Right then the Mexican War happens. People figure out that there are these crazy Rangers in Texas who go everywhere mounted, and they have these repeating pistols. Then Samuel Cole now re-designs something. Now this is called the Walker Colt. It’s this 5-1/2 pound hand cannon that is a six-shooter. If you’ve ever held one, it’s just a thing to hold.

Anyway, it’s the six-shooter. It changes everything. It kills more men than the Rowan Short Sword. It saves Colt from bankruptcy. Colt gets the military contract to make the six-shooters for the Rangers who go into war in Mexico, and absolutely light it up. Nobody’s ever seen this kind of ability to fight.

They’re used as a sort of anti-guerrilla warriors, and nobody can stand with them. It’s the invention of the six-shooter, and it was invented in order to fight Comanches by people who had adapted warfare against Comanches.

Anyway, there’s lots of stories like that. That’s probably my favorite from the book, just because it reaches into capitalism on the East Coast, and Samuel Colt who, by the way, becomes the richest man in America because of this, and on and on and on. It’s a great story.

You were asking earlier about why people don’t know about this. Take somebody like Jack Hays. He should be easily as famous as another guy running around San Antonio in those same years named Davy Crockett. I don’t know why he isn’t, frankly.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Going back to Quanah Parker. He rose to power as the war chief as the Comanches were dwindling in power. They were dwindling because the Rangers figured out how to fight them. But the big reason, the buffalo were being exterminated. This is when you begin talking about that cross-section of capitalism intersecting with the frontier. This is when the buffalo hunter came to power, and they’re just wiping out the buffalo. And that was their food source.

What led Quanah to finally decide … because I think a lot of these plains tribes, they fought going on the reservation, because they knew as soon as that happened, their way of life would be over. They would no longer be the people, or the Comanche.

Sam Gwynne: They were going to have to grow beans and corn.

Brett McKay: Right. Exactly. So they fought until the end. But why did Quanah, this great war chief who was an adept warrior, why did he decide just to finally surrender and head over to Fort Sill?

Sam Gwynne: Well, to go back to something you said a minute ago, what really killed most of the Indians off was proximity to the white man, and white man’s diseases. The great percentages of the Indian tribes died, including Comanches, from cholera and white man’s diseases.

So you had this wave of … well, starting I guess in the 1830s and ’40s and ’50s. It was just, half an entire tribe would be taken out, or two-thirds of an entire tribe. The problem was, the closer you were to the white man’s frontier, the more there was interaction with white men and trade and so forth. And the more the diseases spread.

Quanah Parker happened to be part of a band that lived way out in west Texas. If you’ve ever been to Amarillo, out there. In the Panhandle. And they were, his band, the Quahadis were remote, I guess. They were the most remote band from whatever white frontier you were looking at.

One of the reasons they were able to avoid diseases that they did not themselves go and interact. When they wanted to trade with the Spanish and the Mexicans in Santa Fe, they would trade through these intermediaries called comancheros. Basically, out on the plains there, they were disease free, and therefore their numbers stayed up. This was Quanah’s people.

So what happened by … it’s kind of a cascading effect. The Civil War came, and both North and South governments turned their attentions elsewhere, and allowed the frontier to fester. But after the war was over, the people in charge in Washington pretty soon decided that they were going to put a stop to this.

In the 1870s, you have the first of these big expeditions being sent out. “Okay, we’re now going to end this. We’re going to end this nonsense. How could this tribe with 5,000 people in it or whatever, 5,000 warriors, be holding up the entire advance of western civilization?” Which is the way it would seem.

You have this, not only is it a moment when you have military forces now being unleashed against Quanah and his band out in the Panhandle out in west Texas, but you also have the phenomenon you were talking about, which is the deliberate tolerance by Washington, by the military establishment in particular, of the wholesale killing of all the buffalo on the plains.

And, for a Plains Indian, the buffalo was everything. The buffalo was the food. The buffalo were the clothing, the lodging, the weapons, the food. It was an entire way of life. Everything came from the buffalo. Without the buffalo, a Plains Indian really wasn’t a Plains Indian.

So you have a couple, as I said, a couple of things going on. You have the military now, Quanah and his guys have Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, and Philip Sheridan’s full attention. And these are some serious warriors, who beat the South in the Civil War. And they have their full attention. You have a military campaign being run against, and you have all of their buffalo being slaughtered.

At the end of this last great gasp of all this, the Red River War, it’s pretty much all over for the Plains Indians. Now, Quanah himself, he was never captured. He never lost a battle to the white men. He was out there, he could have stayed out really possibly as long as he wanted to.

But at some point, he realized that that primarily all of the food source was dead. He realized that all of the buffalo were dead. He realized that the lifestyle was going to have to change.

So in 1875, he and the last of the starving Comanches who were now eating prairie dogs, if they could get them, they come in. There really is no choice. They don’t want to go farm beans and corn. And they never did. And when they were given land to do so, they sublet it to white farmers. They never would do it, anyway. They were never going to be anything but who they were, which was hunters of bison or buffalo on the plains.

So Quanah essentially was the last gasp of that. He was one of the last holdouts, the last Comanche holdout. And when he came in, he acknowledged that that if they were going to come into a reservation somewhere, they were going to have to change their ways.

Brett McKay: And he did. I think a lot of Native Americans who went to the reservation, sort of this stereotype and becoming very sullen and not working and just living off the things they get from the government.

But Quanah, he became incredibly industrious. He adapted to the white man’s way, to the point where he, as you said earlier, gained an incredible amount of power, a great amount of wealth, and he also became a celebrity during the late 19th century, early 20th century.

Sam Gwynne: He did; he did this amazing transformation from being one of the most feared warriors of his era. He never talked about what he did, but of course because he was a Comanche, we sort of know what he did. It was brutal, and he was a young man, but he was a true Comanche Plains warrior.

When he had his vision and he went in, he decided he was going to walk the white man’s walk. And he did. One of the interesting things about that was he realized that cattle and land was the name of the game. And he played it just as well as anyone ever did. Certainly as well as any white man did.

He outfoxed the white man in his little cattle leasing schemes. He was absolutely magnificent testifying for the Jerome Commission in Washington, about Comanche land allotments. He was a true leader of his tribe, and he was the leader of his tribe from the time that he surrendered in 1875 until his death in 1911.

But he had became wealthy, built this giant house out on the plains. Never got his … Sorry. He tried to get the U.S. government to build it for him, of course, but they wouldn’t. He got his cattlemen friends to build it for him, this magnificent place called Star House, out on the plains.

If you had walked into Star House in say, 1890, you just wouldn’t believe what you were looking at. He had, well they had six wives in the house. He had what, 20, or 21 children, 19 of whom survived to adulthood. He had children who married white people, he had an adopted white son living with him. He had a French, sorry, a Russian-Mexican cook in there.

He would have Geronimo and the army generals, like Nelson Crook, to dinner in the house, around the house. At any given moment that you would see lodges, tipis, as many as 80 or 90 of them; Comanche tribe members who would come in to get a loan or a gift or money or to be healed, because Quanah founded the Native American Church with his peyote ritual, to get buried. This reservation world revolved around him.

As you said earlier, it would not be accurate to say that most Comanches were willing to follow him and to follow his path. They simply didn’t want to be what the American military establishment and political establishment wanted them to be, which was bean farmers. They never wanted to do that, and they never did that.

Brett McKay: Speaking of other people you might see at his Star House, Teddy Roosevelt, President Teddy Roosevelt.

Sam Gwynne: Yeah, I’m sorry, I forgot Teddy Roosevelt.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Because he made a trip down to Quanah.

Sam Gwynne: He was there once. And it’s great, it’s still sitting out there. It’s falling down now. It’s a true shame that Star House has gone to seed up there in Cache, Oklahoma.

One of the great thrills for me of writing the book was going up there, discovering it. Sitting in the room where that famous picture of Cynthia Ann sat on Quanah’s wall. And into the dining room, where Geronimo had dinner with him and so forth.

Brett McKay: Sam, as you said, this story is a big story; a big story of the American West, the closing of the frontier, but it also has these small stories of families, of individuals. After someone reads this book, what do you hope they walk away with after finishing it?

Sam Gwynne: I think really when I was writing it, I didn’t have an agenda. I wasn’t trying to do anything in particular, except to present a balanced view of the frontier. But it was interesting because I wrote the book, and I started to get these questions that were … Do you know who Don Imus is?

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Sam Gwynne: So I’m being interviewed by Imus. I’m in some studio in Dallas, and Imus loved the book. He came out, he jumped on it, I’m interviewing him, I’m in some studio in Dallas, wearing headphones.

And he goes, “Sam, you wrote this book. Did you have to stop and take a couple of deep breaths before you wrote a complete revisionist history of Native Americans?”

And I’m going, “What are you talking about?” I honestly didn’t know what he meant. Okay, a thousand similar questions later, I now know what he was talking about. And what he was talking about was that you’ve had all of these myths and counter-myths that were flying around, in this country anyway, in the 20th century.

You had this idea that early on, if the army … and you can see this in Hollywood, totally … it’s the army is all good, it’s the cavalry coming and it’s the horrible, mean Indians. That was that idea, the Indians are bad.

Then you had a complete kind of snapback from that. That in the poster book for which was Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, which is that the Indians are noble, gentle people that we just steamrolled over, and broke all our treaties and took their lands and destroyed them … all of which is true, by the way.

But there was that particular side. And the Bury My Heart side of the myth, the Bury My Heart myth had kind of neglected this idea that Indians were powerful in their own right, cruel in their own right, powerful, cruel.

The Comanches were nobody’s fool, and certainly didn’t get rolled over by anybody. They put up a 40-year fight. Well, they drove the Spanish out of the New World and they put up a 40-year fight against the Texans and the Americans.

But it was that sense I guess, and I approached it just as a, I’m a reporter. I was a magazine writer and a newspaper writer. You try to interview both sides and you come to conclusions, but you try to be balanced in your coverage. That’s all I was; I was trying to be balanced.

If I talk about Comanches torturing babies, then I also talk about what the Rangers did to Indians, which was just as horrifying. Not because I was trying to make an ideological point with it, but because it was true. Because the border lands, the frontier were an extremely violent and brutal place. And the violence came from both sides.

You had a culture of vengeance that comes out of it. If you’ve ever seen the movie The Searchers, and the character of John Wayne, it’s just so brilliant. It’s this guy who embodies bitterness of the frontier, and what it’s like to have to lose people. Both sides had that.

I guess what I would like readers to feel, if anything … and this is related to what I was just saying, is that as a reporter, I was balanced. I was sympathetic to both sides, because were the Comanches noble? Yes, they were. They had a fantastic culture, they were family oriented. They were also … You could go on about that. They were also warriors of a very high order who were exceptionally cruel when it came to hostages and captives.

I guess that’s what I would want people to know, is that both myths are incomplete, I guess.

Brett McKay: Yeah, that’s what I took away. It’s basically reiterated the point that human beings, all human beings are complex, messy creatures. Yeah, as I read this, I was horrified by both what the Rangers and the Comanches did. But also inspired by both.

I was sad, what happened with the Comanches and then just seeing that again, it was the people that ended it, basically. That story you told in the end where Quanah goes on one last buffalo hunt.

Sam Gwynne: Oh, isn’t that sad? It’s just-

Brett McKay: There’s nothing there. And that’s when I think they realize, “It’s over.” I was like, “That’s just devastating.”

Yeah, it’s a really great book. Sam Gwynne, thanks so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Sam Gwynne: Well, it’s been a pleasure talking to you too, Brett. Maybe we’ll talk again about the Civil War someday or something.

Brett McKay: No, yeah, you got that book Rebel Yell, about Stonewall Jackson.

Sam Gwynne: Yeah.

Brett McKay: And it’s on my to-read list, so we’re going to make that happen.

Sam Gwynne: All right.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Sam Gwynne. He’s the author of the book Empire of the Summer Moon. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You can find out more information on Sam’s work at scgwynne.com. Or, check out our Show Notes at aom.is/comanches, where you’ll find links to resources, where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM Podcast. Check out our website, artofmanliness.com, where you can find our podcast archives. There’s over 500 episodes there.

We’ve got thousands of articles we’ve written over the years about basically everything: personal finance, physical fitness, how to be better husband, better father.

And if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the Art of Manliness podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code MANLINESS to get one month free on Stitcher Premium.

Once you’ve signed up, download the Stitcher app on IOS or Android. And you can start enjoying ad-free episodes of the Art of Manliness Podcast. Again, stitcherpremium.com, promo code MANLINESS.

If you enjoyed this show and you got something out of it, I’d appreciate it if you give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. Helps out a lot. If you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or family member who you think would get something out of it.

As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay. Reminding you not only to listen to the AOM Podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.